Activision Blizzard is the largest game publisher in the Western world today, generating a staggering $7.5 billion in revenue every year. Along with the only slightly smaller behemoth Electronic Arts and a few Japanese competitors, Activision for all intents and purposes is the face of gaming as a mainstream, mass-media phenomenon. Even as the gaming intelligentsia looks askance at Activision for their unshakeable fixation on sequels and tried-and-true formulas, the general public just can’t seem to get enough Call of Duty, Guitar Hero, World of Warcraft, and Candy Crush Saga. Likewise, Bobby Kotick, who has sat in the CEO’s chair at Activision for over a quarter of a century now, is as hated by gamers of a certain progressive sensibility as he is loved by the investment community.

But Activision’s story could have — perhaps by all rights should have — gone very differently. When Kotick became CEO, the company was a shambling wreck that hadn’t been consistently profitable in almost a decade. Mismanagement combined with bad luck had driven it to the ragged edge of oblivion. What to a large degree saved Activision and made the world safe for World of Warcraft was, of all things, a defunct maker of text adventures which longtime readers of this ongoing history have gotten to know quite well. The fact that Infocom, the red-headed stepchild a previous Activision CEO had never wanted, is directly responsible for Activision’s continuing existence today is one of the strangest aspects of both companies’ stories.

The reinvention of Activision engineered by Bobby Kotick in the early 1990s was actually the company’s third in less than a decade.

Activision 1.0 was founded in 1979 by four former Atari programmers known as the “Fantastic Four,” along with a former music-industry executive named Jim Levy. Their founding tenets were that Atari VCS owners deserved better games than the console’s parent was currently giving them, and that Atari VCS game programmers deserved more recognition and more money than were currently forthcoming from the same source. They parlayed that philosophy into one of the most remarkable success stories of the first great videogame boom; their game Pitfall! alone sold more than 4 million copies in 1982. It would, alas, be a long, long time before Activision would enjoy success like that again.

Following the Great Videogame Crash of 1983, Levy tried to remake Activision into a publisher of home-computer games with a certain high-concept, artsy air. But, while the ambitions of releases like Little Computer People, Alter Ego, and Portal still make them interesting case studies today, Activision 2.0 generated few outright hits. Six months after Levy had acquired Infocom, the preeminent maker of artsy computer games, in mid-1986, he was forced out by his board.

Levy’s replacement was a corporate lawyer named Bruce Davis. He nixed the artsy fare, doubled down on licensed titles, and tried to establish Activision 3.0 as a maker of mass-market general-purpose computer software as well as games. Eighteen months into his tenure, he changed the company’s name to Mediagenic to reflect this new identity. But the new products were, like the new name, mostly bland in a soulless corporate way that, in the opinion of many, reflected Davis’s own personality all too accurately. By decade’s end, Mediagenic was regarded as an important player within their industry at least as much for their distributional clout, a legacy of their early days of Atari VCS success, as for the games and software they published under their own imprint. A good chunk of the industry used Mediagenic’s network to distribute their wares as members of the company’s affiliated-labels program.

Then the loss of a major lawsuit, combined with a slow accretion of questionable decisions from Davis, led to a complete implosion in 1990. The piggy bank provided by Activision 1.0’s success had finally run dry, and most observers assumed that was that for Mediagenic — or Activision, or whatever they preferred to call themselves today.

But over the course of 1991, a fast-talking wiz kid named Bobby Kotick seized control of the mortally wounded mastodon and put it through the wringer of bankruptcy. What emerged by the end of that year was so transformed as to raise the philosophical question of whether it ought to be considered the same entity at all. The new company employed just 10 percent as many people as the old (25 rather than 250) and was headquartered in a different region entirely (Los Angeles rather than Silicon Valley). It even had a new name — or, rather, an old one. Perhaps the smartest move Kotick ever made was to reclaim the company’s old appellation of “Activision,” still redolent for many of the nostalgia-rich first golden age of videogames, in lieu of the universally mocked corporatese of “Mediagenic.” Activision 4.0, the name reversion seemed to say, wouldn’t be afraid of their heritage in the way that versions 2.0 and 3.0 had been. Nor would they be shy about labeling themselves a maker of games, full stop; Mediagenic’s lines of “personal-productivity” software and the like were among the first things Kotick trashed.

Kotick was still considerably short of his thirtieth birthday when he took on the role of Activision’s supreme leader, but he felt like he’d been waiting for this opportunity forever. He’d spent much of the previous decade sniffing around at the margins of the industry, looking for a way to become a mover and shaker of note. (In 1987, for instance, at the tender age of 24, he’d made a serious attempt to scrape together a pool of investors to buy the computer company Commodore.) Now, at last, he had his chance to be a difference maker.

It was indeed a grand chance, but it was also an extremely tenuous one. He had been able to save Activision — save it for the time being, that is — only by mortgaging some 95 percent of it to its numerous creditors. These creditors-cum-investors were empowered to pull the plug at any time; Kotick himself maintained his position as CEO only by their grace. He needed product to stop the bleeding and add some black to the sea of red ink that was Activision’s books, thereby to show the creditors that their forbearance toward this tottering company with a snot-nosed greenhorn at the head hadn’t been a mistake. But where was said product to come from? Activision was starved for cash even as the typical game-development budget in the industry around them was increasing almost exponentially year over year. And it wasn’t as if third-party developers were lining up to work with them; they’d stiffed half the industry in the process of going through bankruptcy.

To get the product spigot flowing again, Kotick found a partner to join him in the executive suite. Peter Doctorow had spent the last six years or so with Accolade (a company ironically founded by two ex-Activision developers in 1984, in a fashion amusingly similar to the way that restless Atari programmers had begotten Activision). In the role of product-development guru, Doctorow had done much to create and maintain Accolade’s reputation as a maker of attractive and accessible games with natural commercial appeal. Activision, on the other hand, hadn’t enjoyed a comparable reputation since the heyday of the Atari VCS. Jumping ship from the successful Accolade to an Activision on life support would have struck most as a fool’s leap, but Kotick could be very persuasive. He managed to tempt Doctorow away with the title of president and the promise of an opportunity to build something entirely new from the ground up.

Of course, building materials for the new thing could and should still be scrounged from the ruins of Mediagenic whenever possible. After arriving at Activision, Doctorow thus made his first priority an inventory of what he already had to work with in the form of technology and intellectual property. On the whole, it wasn’t a pretty picture. Activision had never been particularly good at spawning the surefire franchises that gaming executives love. There were no Leisure Suit Larrys or Lord Britishes lurking in their archives — much less any Super Marios. Pitfall!, the most famous and successful title of all from the Atari VCS halcyon days, might be a candidate for revival, but its simple platforming charms were at odds with where computer gaming was and where it seemed to be going in the early 1990s; the talk in the industry was all about multimedia, live-action video, interactive movies, and story, story, story. Pitfall! would have been a more natural fit on the consoles, but Kotick and Doctorow weren’t sure they had the resources to compete as of yet in those hyper-competitive, expensive-to-enter walled gardens. Their first beachhead, they decided, ought to be on computers.

In that context, there were all those old Infocom games… was there some commercial potential there? Certainly Zork still had more name recognition than any property in the Activision stable other than Pitfall!.

Ironically, the question of a potential Infocom revival would have been moot if Bruce Davis had gotten his way. He had never wanted Infocom, having advised his predecessor Jim Levy strongly against acquiring them when he was still a mere paid consultant. When Infocom delivered a long string of poor-selling games over the course of 1987 and 1988, he felt vindicated, and justified in ordering their offices closed permanently in the spring of 1989.

Even after that seemingly final insult, Davis continued to make clear his lack of respect for Infocom. During the mad scramble for cash preceding the ultimate collapse of Mediagenic, he called several people in the industry, including Ken Williams at Sierra and Bob Bates at the newly founded Legend Entertainment, to see if they would be interested in buying the whole Infocom legacy outright — including games, copyrights, trademarks, source code, and the whole stack of development tools. He dropped his asking price as low as $25,000 without finding a taker; the multimedia-obsessed Williams had never had much interest in text adventures, and Bates was trying to get Legend off the ground and simply didn’t have the money to spare.

When a Mediagenic producer named Kelly Zmak learned what Davis was doing, he told him he was crazy. Zmak said that he believed there was still far more than $25,000 worth of value in the Infocom properties, in the form of nostalgia if nothing else. He believed there would be a market for a compilation of Infocom games, which were now available only as pricey out-of-print collectibles. Davis was skeptical — the appeal of Infocom’s games had always been lost on him — but told Zmak that, if he could put such a thing together for no more than $10,000, they might as well give it a try. Any port in a storm, as they say.

As it happened, Mediagenic’s downfall was complete before Zmak could get his proposed compilation into stores. But he was one of the few who got to keep his job with the resurrected company, and he made it clear to his new managers that he still believed there was real money to be made from the Infocom legacy. Kotick and Doctorow agreed to let him finish up his interrupted project.

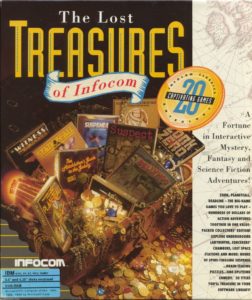

And so one of the first products from the new Activision 4.0 became a collection of old games from the eras of Activision 3.0, 2.0, and even 1.0. It was known as The Lost Treasures of Infocom, and first entered shops very early in 1992.

Activision’s stewardship of the legacy that had been bequeathed to them was about as respectful as one could hope for under the circumstances. The compilation included 20 of the 35 canonical Infocom games. The selection felt a little random; while most of the really big, iconic titles — like all of the Zork games, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the Enchanter trilogy, and Planetfall — were included, the 100,000-plus-selling Leather Goddesses of Phobos and Wishbringer were oddly absent. The feelies that had been such an important part of the Infocom experience were reduced to badly photocopied facsimiles lumped together in a thick, cheaply printed black-and-white manual — if, that is, they made the package at all. The compilers’ choices of which feelies ought to be included were as hit-and-miss as their selection of games, and in at least one case — that of Ballyhoo — the loss of an essential feelie rendered a game unwinnable without recourse to outside resources. Hardcore Infocom fans had good reason to bemoan this ugly mockery of the original games’ lovingly crafted packaging. “Where is the soul?” asked one of them in print, speaking for them all.

But any real or perceived lack of soul didn’t stop people from buying the thing. In fact, people bought it in greater numbers than even Kelly Zmak had dared to predict. At least 100,000 copies of The Lost Treasures of Infocom were sold — numbers better than any individual Infocom game had managed since 1986 — at a typical street price of about $60. With a response like that, Activision wasted no time in releasing most of the remaining games as The Lost Treasures of Infocom II, to sales that were almost as good. Along with Legend Entertainment’s final few illustrated text adventures, Lost Treasures I and II mark the last gasps of interactive fiction as a force in mainstream commercial American computer gaming.

The Lost Treasures of Infocom — the only shovelware compilation ever to spark a full-on artistic movement.

Yet these two early examples of the soon-to-be-ubiquitous practice of the shovelware compilation constitute a form of beginning as well as ending. By collecting the vast majority of the Infocom legacy in one place, they cemented the idea of an established Infocom canon of Great Works, providing all those who would seek to make or play text adventures in the future with an easily accessible shared heritage from which to draw. For the Renaissance of amateur interactive fiction that would take firm hold by the mid-1990s, the Lost Treasures would become a sort of equivalent to what The Complete Works of William Shakespeare means to English literature. Had such heretofore obscure but groundbreaking Infocom releases as, say, Nord and Bert Couldn’t Make Head or Tail of It and Plundered Hearts not been collected in this manner, it’s doubtful whether they ever could have become as influential as they would eventually prove. Certainly a considerable percentage of the figures who would go on to make the Interactive Fiction Renaissance a reality completed their Infocom collection or even discovered the company’s rich legacy for the first time thanks to the Lost Treasures compilations.

Brian Eno once famously said that, while only about 30,000 people bought the Velvet Underground’s debut album, every one of them who did went out and started a band. A similar bit of hyperbole might be applied to the 100,000-and-change who bought Lost Treasures. These compilations did much to change perceptions of Infocom, from a mere interesting relic of an earlier era of gaming into something timeless and, well, canonical — a rich literary tradition that deserved to be maintained and further developed. It’s fair to ask whether the entire vibrant ecosystem of interactive fiction that remains with us today, in the form of such entities as the annual IF Comp and the Inform programming language, would ever have come to exist absent the Lost Treasures. Their importance to everything that would follow in interactive fiction is so pronounced that anecdotes involving them will doubtless continue to surface again and again as we observe the birth of a new community built around the love of text and parsers in future articles on this site.

For Activision, on the other hand, the Lost Treasures compilations made a much more immediate and practical difference. What with their development costs of close to zero and their no-frills packaging that hadn’t cost all that much more to put together, every copy sold was as close to pure profit as a game could possibly get. They made an immediate difference to Activision’s financial picture, giving them some desperately needed breathing room to think about next steps.

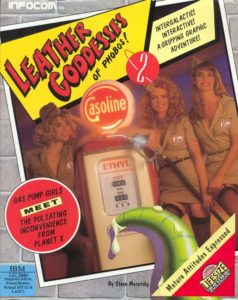

Observing the success of the compilations, Peter Doctorow was inclined to return to the Infocom well again. In fact, he had for some time now been eyeing Leather Goddesses of Phobos, Infocom’s last genuine hit, with interest. In the time since it had sold 130,000 copies in 1986, similarly risqué adventure games had become a profitable niche market: Sierra’s Leisure Suit Larry series, Legend’s Spellcasting series, and Accolade’s Les Manley series had all done more or less well. There ought to be a space, Doctorow reasoned, for a sequel to the game which had started the trend by demonstrating that, in games as just about everywhere else, Sex Sells. Hewing to this timeless maxim, he had made a point of holding the first Leather Goddesses out of the Lost Treasures compilations in favor of giving it its own re-release as a standalone $10 budget title — the only one of the old Infocom games to be accorded this honor.

Doctorow had a tool which he very much wanted to use in the service of a new adventure game. Whilst casting through the odds and ends of technology left over from the Mediagenic days, he had come upon something known as the Multimedia Applications Development Environment, the work of a small internal team of developers headed by one William Volk. MADE had been designed to facilitate immersive multimedia environments under MS-DOS that were much like the Apple Macintosh’s widely lauded HyperCard environment. In fact, Mediagenic had used it just before the wheels had come off to publish a colorized MS-DOS port of The Manhole, Rand and Robyn Miller’s unique HyperCard-based “fantasy exploration for children of all ages.” Volk and most of his people were among the survivors from the old times still around at the new Activision, and the combination of the MADE engine with Leather Goddesses struck Doctorow as a commercially potent one. He thus signed Steve Meretzky, designer of the original game, to write a sequel to this second most popular game he had ever worked on. (The most popular of all, of course, had been Hitchhiker’s, which was off limits thanks to the complications of licensing.)

But from the beginning, the project was beset by cognitive dissonance, alongside extreme pressure, born of Activision’s precarious finances, to just get the game done as quickly as possible. Activision’s management had decided that adventure games in the multimedia age ought to be capable of appealing to a far wider, less stereotypically eggheaded audience than the games of yore, and therefore issued firm instructions to Meretzky and the rest of the development team to include only the simplest of puzzles. Yet this prioritization of simplicity above all else rather belied the new game’s status as a sequel to an Infocom game which, in addition to its lurid content, had featured arguably the best set of interlocking puzzles Meretzky had ever come up with. The first Leather Goddesses had been a veritable master class in classic adventure-game design. The second would be… something else.

Which isn’t to say that the sequel didn’t incorporate some original ideas of its own; they were just orthogonal to those that had made the original so great. Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2: Gas Pump Girls Meet the Pulsating Inconvenience from Planet X really wanted to a be a CD-based title, but a critical mass of CD-ROM-equipped computers just wasn’t quite there yet at the time it was made. So, when it shipped in May of 1992 it filled 17 (!) floppy disks, using the space mostly for, as Activision’s advertisements proudly trumpeted in somewhat mangled diction, “more than an hour of amazing digital sound track!” Because a fair number of MS-DOS computer owners still didn’t have sound cards at this point, and because a fair proportion of those that did had older models of same that weren’t up to the task of delivering digitized audio as opposed to synthesized sounds and music, Activision also included a “LifeSize Sound Enhancer” in every box — a little gadget with a basic digital-to-analog circuit and a speaker inside it, which could be plugged into the printer port to make the game talk. This addition pushed the price up into the $60 range, making the game a tough sell for the bare few hours of content it offered — particularly if you already had a decent sound card and thus didn’t even need the hardware gadget you were being forced to pay for. Indeed, thanks to those 17 floppy disks, Leather Goddesses 2 would come perilously close to taking most gamers longer to install than it would to actually play.

That said, brevity was among the least of the game’s sins: Leather Goddesses 2 truly was a comprehensive creative disaster. The fact that this entire game was built from an overly literal interpretation of a tossed-off joke at the end of its predecessor says it all really. Meretzky’s designs had been getting lazier for years by the time this one arrived, but this game, his first to rely solely on a point-and-click interface, marked a new low for him. Not only were the brilliant puzzles that used to do at least as much as his humor to make his games special entirely absent, but so was all of the subversive edge to his writing. To be fair, Activision’s determination to make the game as accessible as possible — read, trivially easy — may have largely accounted for the former lack. Meretzky chafed at watching much of the puzzle design — if this game’s rudimentary interactivity can even be described using those words — get put together without him in Activision’s offices, a continent away from his Boston home. The careless writing, however, is harder to make excuses for.

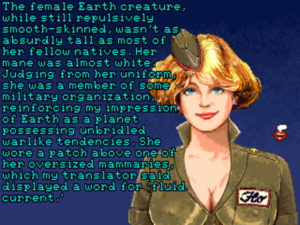

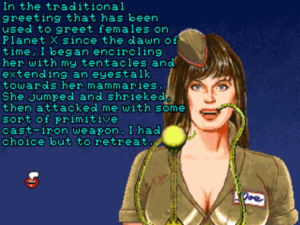

In the tradition of the first Leather Goddesses, the sequel lets you choose to play as a man or a woman — or, this time, as an alien of indeterminate sex.

Still, this game is obviously designed for the proverbial male gaze. The real question is, why were all these attempts to be sexy in games so painfully, despressingly unsexy? Has anyone ever gotten really turned on by a picture like this one?

Earlier Meretzky games had known they were stupid, and that smart sense of self-awareness blinking through between the stupid had been their saving grace when they wandered into questionable, even borderline offensive territory. This one, on the other hand, was as introspective as one of the bimbos who lived within it. Was this really the same designer who just seven years before had so unabashedly aimed for Meaning in the most literary sense with A Mind Forever Voyaging? During his time at Infocom, Meretzky had been the Man of 1000 Ideas, who could rattle off densely packed pages full of games he wanted to make when given the least bit of encouragement. And yet by the end of 1992, he had made basically the same game four times in a row, with diminishing returns every time out. Just how far did he think he could ride scantily clad babes and broad innuendo? The shtick was wearing thin.

The women in many games of this ilk appear to be assembled from spare parts that don’t quite fit together properly.

Here, though, that would seem to literally be the case. These two girls have the exact same breasts.

In his perceptive review of Leather Goddesses 2 for Computer Gaming World magazine, Chris Lombardi pointed out how far Meretzky had fallen, how cheap and exploitative the game felt — and not even cheap and exploitative in a good way, for those who really were looking for titillation above all else.

The treatment of sex in LGOP2 seems so gratuitous, and adolescent, and (to use a friend’s favorite adjective for pop music) insipid. The game’s “explicit” visual content is all very tame (no more explicit than a beer commercial, really) and, for the most part, involves rather mediocre images of women in tight shirts, garters, or leather, most with impossibly protruding nipples. It’s the stuff of a Wally Cleaver daydream, which is appropriate to the game’s context, I suppose.

It appears quite innocuous at first, yet as I played along I began to sense an underlying attitude running through it all that can best be seen in the use of a whorehouse in the game. When one approaches this whorehouse, one is served a menu of a dozen or so names to choose from. Choosing a name takes players to a harlot’s room and affords them a “look at the goods.” Though loosely integrated into the storyline, it is all too apparent that it is merely an excuse for a slideshow of more rather average drawings of women.

You have to wonder what Activision was thinking. Do they imagine adults are turned on or, at minimum, entertained by this stuff? If they do, then I think they’ve misunderstood their market. And that must be the case, for the only other possibility is to suggest that their real target market is actually, and more insidiously, a younger, larger slice of the computer-game demographic pie.

On the whole, Lombardi was kinder to the game than I would have been, but his review nevertheless raised the ire of Peter Doctorow, who wrote in to the magazine with an ad hominem response: “It seems clear to me that you must be among those who long for the good old days, when films were black and white, comic books were a dime, and you could get an American-made gas guzzler with a distinct personality, meticulously designed taillights, and a grill reminiscent of a gargantuan grin. Sadly, the merry band that was Infocom can no longer be supported with text adventures.”

It seldom profits a creator to attempt to rebut a reviewer’s opinion, as Doctorow ought to have been experienced enough to know. His graceless accusation of Ludditism, which didn’t even address the real concerns Lombardi stated in his review, is perhaps actually a response to a vocal minority of the Infocom hardcore who were guaranteed to give Activision grief for any attempt to drag a beloved legacy into the multimedia age. Even more so, though, it was a sign of the extreme financial duress under which Activision still labored. Computer Gaming World was widely accepted as the American journal of record for the hobby in question, and their opinions could make or break a game’s commercial prospects. The lukewarm review doubtless contributed to Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2‘s failure to sell anywhere near as many copies as the Lost Treasures compilations — and at a time when Activision couldn’t afford to be releasing flops.

So, for more reasons than one, Leather Goddesses 2 would go down in history as an embarrassing blot on the CV of everyone involved. Sex, it seemed, didn’t always sell after all — not when it was done this poorly.

One might have thought that the failure of Leather Goddesses 2 would convince Activision not to attempt any further Infocom revivals. Yet once the smoke cleared even the defensive Doctorow could recognize that its execution had been, to say the least, lacking. And there still remained the counterexample of the Lost Treasures compilations, which were continuing to sell briskly. Activision thus decided to try again — this time with a far more concerted, better-funded effort that would exploit the most famous Infocom brand of all. Zork itself was about to make a splashy return to center stage.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of April 1992, July 1992, and October 1992; Questbusters of February 1992 and August 1992; Compute! of November 1987; Amazing Computing of April 1992; Commodore Magazine of July 1989; .info of April 1992. Online sources include Roger J. Long’s review of the first Lost Treasures compilation. Some of this article is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Finally, my huge thanks to William Volk and Bob Bates for sharing their memories and impressions with me in personal interviews.)