You ask why there are movements in movie history. Why all of a sudden there are great Japanese films, or great Italian films, or great Australian films, or whatever. And it’s usually because there are a number of people that cross-pollinated each other.

— Francis Ford Coppola

Over the course of the late 1970s and early 1980s, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg remade the very business of film-making for better or for worse, shifting its focus from message movies and character dramas to the special-effects-heavy, escapist blockbusters that still drive Hollywood’s profits to this day. These events, which we might call the rise of the culture of the blockbuster, have long since been enshrined into the canonical history of film, filed under the names of these two leading lights.

Yet no two personalities could possibly have brought about such a dramatic shift on their own. Orbiting around Lucas and Spielberg was an entire galaxy of less prominent talents whose professional lives were profoundly affected by their association with these two new faces of modern Hollywood. They were the fellow travelers who helped Lucas and Spielberg to change the movie industry, all without ever quite being aware that they were part of any particular movement at all. Among the group were names like John Milius, Walter Murch, Willard Huyck, Randall Kleiser, Matthew Robbins, and Hal Barwood. “I can’t speak for the others,” says Robbins, “but it was my impression that nobody had the foggiest idea that there was any ‘next wave’ coming. Nobody had set their sights — except perhaps for George [Lucas].”

Out of this group of slightly lesser but undeniably accomplished lights, Hal Barwood is our special person of interest for today. He first met George Lucas in the mid-1960s, when the two were students together in the University of Southern California’s film program. Lucas, who had only recently abandoned his original dream of driving race cars in favor of this new one of making movies, was shy almost to the point of complete inarticulateness, and was far more comfortable futzing over a Moviola editing machine than he was trying to cajole live actors into doing his bidding. Nevertheless, there was a drive to this awkward young man that gradually revealed itself over the course of a longer acquaintance, and Barwood — on the surface, a far more assertive, impressive personality — soon joined Lucas’s loose clique in the role of follower rather than leader. Flying in the face of a Hollywood culture which valued realistic character dramas above all else, Lucas, Barwood, and their pals loved science fiction and fantasy, didn’t consider escapism to be a dirty word, and found the visual aesthetics of film to be every bit as interesting as their actors’ performances.

The bond thus forged would remain strong for many years. When Lucas, through the intermediation of his friend and mentor Francis Ford Coppola, got the chance to direct an actual feature film, Barwood added the first professional film credit to his own CV by helping out with the special effects on what became THX-1138, a foreboding, low-budget work of dystopic science fiction that was released to little attention in 1971. When Lucas hit it big two years later with his very different second film, the warmly nostalgic coming-of-age story American Graffiti, he bought a big old ramshackle mansion in San Anselmo, California, with the first of the proceeds, and Barwood became one of several fellow travelers who joined him and his wife in this first headquarters of a nascent corporate entity called Lucasfilm.

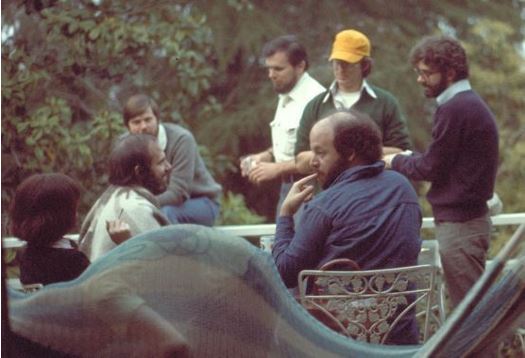

George Lucas, standing at far right, discusses Star Wars with his sounding board in the mid-1970s. Steve Spielberg is wearing the orange cap, and Hal Barwood sits on the fence behind him.

Working together with his good friend Matthew Robbins, Barwood wrote a science-fiction script called Star Dancing during the same period. The two commissioned a former Boeing technical illustrator and CBS animator named Ralph McQuarrie to paint some concept art, thereby to help them pitch the project to the studios. In the end, though, Star Dancing never went anywhere — until Lucas, who was toying with ideas for a second, more crowd-pleasing science-fiction movie of his own, saw McQuarrie’s paintings and was greatly inspired by them, hiring him to develop the vision further for what would become Star Wars. McQuarrie’s concept art had much to do with the eventual green-lighting of Star Wars by 20th Century Fox, and he would continue to shape the look of that film and its two sequels over the long course of their production.

Barwood and Robbins, for their part, became two of the eight people entrusted to read the first draft of the film’s script. He and the others in that San Anselmo house then proceeded to slowly shape the Star Wars script we know today over the course of draft after draft.

Even as they helped Lucas with Star Wars, Barwood and Robbins were still trying to make it as screenwriters in their own right. They sold their first script, a chase caper called The Sugarland Express, to George Lucas’s up-and-coming pal Steven Spielberg, a more recently arrived member of the San Anselmo collective; he turned it into his feature-film directorial debut in 1974. More screenwriting followed, including an uncredited rewrite of the 1977 Spielberg blockbuster Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the first film to benefit in a big way commercially from the new interest in science fiction ignited by Star Wars, which had been released about six months prior to it.

Yet the pair found screenwriting to be an inherently frustrating profession in an industry which regarded the director as a movie’s ultimate creative voice. “In writing, you’re always watching directors ruin your stuff,” says Barwood. “As a writer, you have a certain flavor, style, and emphasis in mind when you write the script, and you’re always shocked when the director comes back with something else. There’s a tendency to want to get your hands on the controls and do it yourself.” Accordingly, Matthew Robbins personally directed the duo’s 1978 comedy Corvette Summer, starring Mark Hamill — Luke Skywalker himself — in his first big post-Star Wars role. The film was a commercial success, even if the reviews weren’t great; it turned out that there was only so much you could do with Hamill, the very archetype of an actor who’s good in one role and one role only.

The duo’s next big project was their most ambitious, time-consuming, and expensive undertaking yet. Dragonslayer was a fantasy epic based loosely on the legend of St. George and the dragon, and was once again directed by Robbins. The special effects were provided by George Lucas’s Industrial Light and Magic. In fact, Dragonslayer became the very first outside, non-Star Wars project the famous effects house took on. Being at least as challenging as anything in any of the Star Wars films, the Dragonslayer effects took them some eighteen months to complete.

Dragonslayer‘s pedigree was such that it was widely heralded in the Hollywood trade press as a “surefire success” prior to its release. But it had the misfortune to arrive in theaters on June 26, 1981, two weeks after Lucas and Spielberg’s new blockbuster collaboration, Raiders of the Lost Ark. The latter film shared with Dragonslayer the distributor Paramount Pictures. “Paramount was quite satisfied to go through the summer with the money they were going to get from Raiders of the Lost Ark,” says Barwood, “and paid no attention to our movie. They just dropped it. They just forgot about it.” Dragonslayer flopped utterly, badly damaging the duo’s reputation inside Hollywood as purveyors of marketable cinema.

Barwood got his one and only chance to direct a feature film in 1985, when he took the reins of Warning Sign, yet another screenplay by himself and Robbins. In a telling sign of the damage Dragonslayer‘s failure had done to their careers, this latest film, a fairly predictable thriller about a genetic-engineering project run amok, had a budget of about one-quarter what the duo had had to work with on their fantasy epic. It garnered mediocre reviews and box-office receipts, and no one seemed eager to entrust its first-time director with more movies. Barwood and Robbins, both frustrated by the directions their careers had taken since Corvette Summer, decided their long creative partnership had run its course.

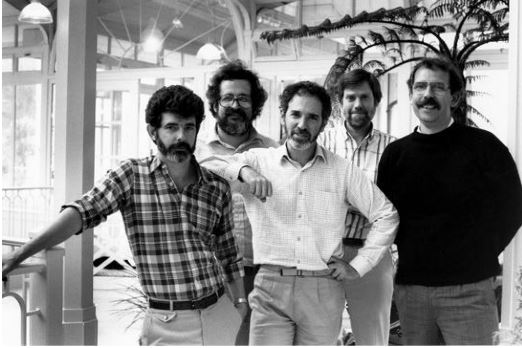

George Lucas (far left) and some of his old compatriots at Skywalker Ranch in the mid-1980s. Matthew Robbins is third from left, Hal Barwood fourth from left.

So, Hal Barwood found himself at something of a loose end as the 1980s drew to a close. He was still friendly with George Lucas, if perhaps not quite the bosom buddy he once had been, and he still knew many of the most powerful people in the movie industry, starting with Steven Spielberg — who had gradually shown himself to be, even more so than Lucas, the personification of the new, blockbuster-oriented Hollywood, his prolific career cruising along with hit after hit. But, as Spielberg basked in his success, Barwood had parted ways with his partner and seen his directorial debut become a bust. He hadn’t had a hand in a real hit since 1978, and he hadn’t sold a script at all in quite some time. Just to rub salt into the wounds, his old compatriot Matthew Robbins managed to score another modest hit of his own at last just after the breakup, with the distinctly Spielbergian science-fiction comedy Batteries Not Included, which he directed and whose screenplay he had written with others.

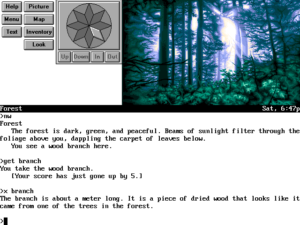

Perhaps it was time for Hal Barwood to try something completely different. He had actually been mulling over his future in this cutthroat industry for some time already. During the promotional tour for Warning Sign, he had made a rather odd comment to Starlog magazine, accompanied by what his interviewer described as a “nervous laugh”: “If movies don’t pan out for me, I have a second career lurking around the corner in entertainment software, working on animated computer games, which I’m doing right now. They’re very sophisticated, animated adventure games.”

Barwood had in fact been fascinated by computers for a long time, ever since he had first encountered the hulking number-crunching monstrosities of the 1960s at university. In 1980, while hanging around the set of Dragonslayer, he had programmed his first game on a state-of-the-art HP-41C calculator as a way of passing the time between takes. Soon after, he joined the PC Revolution, buying an Apple II and starting to tinker. He worked for years on a CRPG for that machine in his spare time — worked for so long that it was still in progress when the Apple II games market began to collapse. Undaunted, he moved on to a Macintosh, where he programmed a storyboarding system for movie makers like himself in HyperCard, selling it as shareware under the name of StoryCard.

With all this experience behind him, it was natural for Barwood now to consider a future in games instead of movies — a future in an industry where the budgets were smaller, the competitors were fewer, and it was much easier to come up with an idea and actually see it through from beginning to end in something like its original form. All of this made quite a contrast to the industry where he had cut his teeth. “The movie business is very difficult for most of us,” he says. “We don’t usually get a majority of our projects to completion. Most of our dreams turn into screenplays, but they stall out at that stage.”

Given his long association with George Lucas, Barwood decided to talk to Lucasfilm Games. They were more than happy to have him, and could certainly relate to the reasons that brought him to their doorstep — for, like Barwood, they had had a somewhat complicated life of it to date in the long shadow cast by Lucas.

Before there was Lucasfilm Games, there was the Lucasfilm Computer Division, founded in 1979 to experiment with computer animation and digital effects, technologies with obvious applications for the making of special-effects-heavy films. Lucasfilm Games had been almost literally an afterthought, an outgrowth of the Computer Division that was formed in 1982, a time when George Lucas and Lucasfilm were flying high and throwing money about willy-nilly.

In those days, a hit computer game, one into which Lucasfilm Games had poured their hearts and souls, might be worth about as much to the parent company’s bottom line as a single Jawa action figure — such was the difference in scale between the computer-games industry of the early 1980s and the other markets where Lucasfilm was a player. George Lucas personally had absolutely no interest in or understanding of games, which didn’t do much for the games division’s profile inside his company. And, most frustrating of all for the young developers who came to work for The House That Star Wars Built, they weren’t allowed to make Star Wars games — nor, for that matter, even Indiana Jones games — thanks to Lucas having signed away those rights to others at the height of the Atari VCS fad. Noah Falstein, one of those young developers, would later characterize this situation as “the best thing that could have happened” to them, as it forced them to develop original fictions instead — leading, he believes, to better, more original games. At the time, however, it couldn’t help but frustrate that the only Lucasfilm properties the games division had access to were middling fare like Labyrinth.

Still, somebody inside Lucasfilm apparently believed in the low-profile division’s potential, for it survived the great bloodletting of the mid-1980s. In response to George Lucas’s expensive divorce settlement and the realization that, with the Star Wars trilogy now completed, there would be no more enormous guaranteed paydays in the future, the company’s executives, with Lucas’s tacit blessing, took an axe to many of their more uncertain or idealistic ventures at that time. Among the divisions that were sold off was the rest of the Computer Division that had indirectly spawned Lucasfilm Games; it would go on to worldwide fame and fortune under the name of Pixar. As for the games people: in 1986, they got to move into some of the vacant space all the downsizing had opened up at Skywalker Ranch, Lucasfilm’s sprawling summer camp cum corporate campus in Marin County, California.

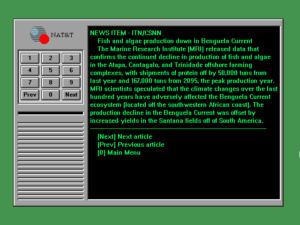

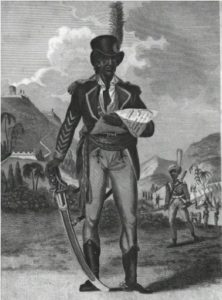

The wall separating Lucasfilm Games from the parent company’s most desirable intellectual properties finally began to fall at the end of the 1980s, when the games people were given access to… no, not yet to Star Wars, but to the next best thing: Indiana Jones, George Lucas’s other great cinematic success story. Raiders of the Lost Ark, the first breakneck tale of the adventurous 1930s archaeologist, as conceived by Lucas and passed on to Steven Spielberg to direct, had become the highest-grossing film of 1981 by nearly a factor of two over its nearest competitor; as we’ve seen, it had trampled less fortunate rivals like poor Hal Barwood’s Dragonslayer into the dust during that year’s summer-blockbuster season. A 1984 sequel, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, had done nearly as well. Now a third and presumably final film, to be called Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, was in the offing. With the earlier licensing deals they had made for the property now expired, the parent company wanted their games division to make an adventure game out of it.

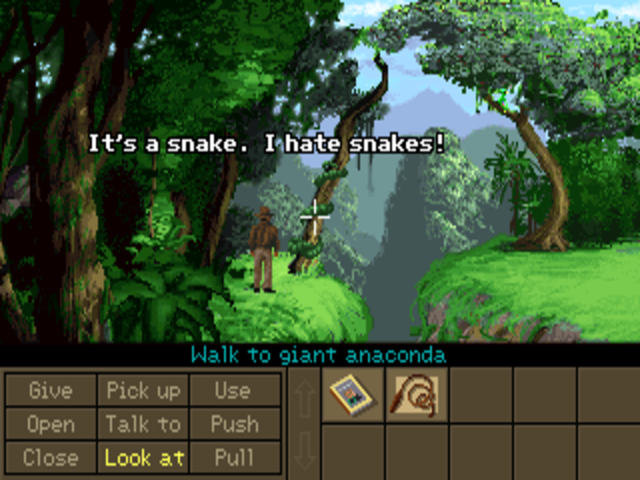

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure [1]An Action Game was also published under the auspices of Lucasfilm Games, but its development was outsourced to a British house. was designed by Noah Falstein, David Fox, and Ron Gilbert, all of whom had worked on previous Lucasfilm adventure games, and written using the division’s established SCUMM adventuring engine. This committee approach to the game’s design is typical of the workaday nature of the project as a whole. The designers were given a copy of the movie’s shooting script, and were expected not to deviate too much from it. Ron Gilbert, a comedy writer by disposition and talent, found the need to play it relatively straight particularly frustrating, but it seems safe to say that all of the designers’ creative instincts were somewhat hemmed in by the project’s fixed rules. The end result, while competently executed, hasn’t the same vim and vinegar as Maniac Mansion, the first SCUMM adventure, nor even Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, the rather less satisfying second SCUMM game.

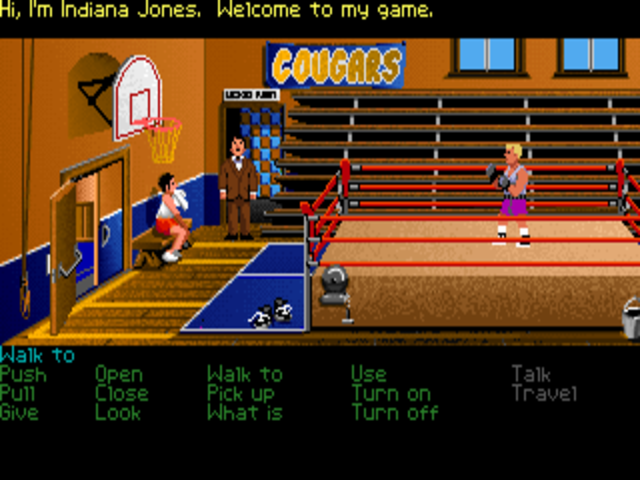

The boxing scene which opens the game of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade was a part of the film’s original script which was cut in the editing room. Scenes like these make the game almost of more interest to film historians than game historians, serving as a window into the movie as it was conceived by its screenwriter Jeffrey Boam.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the game arises from the fact that its designers were adapting from the shooting script rather than the finished movie, which they got to see in the Skywalker Ranch theater only when their own project was in the final stages of bug-swatting and polishing. They actually implemented parts of Jeffrey Boam’s script for the movie far more faithfully than Steven Spielberg wound up doing, including numerous scenes — like the boxing sequence at the very beginning of the game — that wound up being cut from the movie. Nevertheless, the game suffers from the fundamental problem of all such overly faithful adaptations from other media: if you’ve seen the movie — and it seemed safe to assume that just about everybody who played the game had seen the movie — what’s the point in walking through the same story again in game form? The designers went to considerable lengths to accommodate curious (or cantankerous) players who make different choices from those of Indiana Jones in the movie, turning their choices into viable alternative pathways rather than mere game overs. But there was only so much they could do in even that respect, given the constraints under which they labored.

Of course, licensed games exist first and foremost because licenses sell games, not because they lead to better ones. Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade became the cinematic blockbuster of the year upon its release in May of 1989, and the game also did extremely well when it hit stores a few weeks later. Having taken this first step into the territory of Lucasfilm’s biggest franchises and been so amply rewarded for it, the people at the games division naturally wanted to keep the good times going. There were likely to be no more Indiana Jones movies; Harrison Ford, the series’s famously prickly star, was publicly declaring himself to be through with playing the character. But did that necessarily mean that there couldn’t be more Indiana Jones games? With the license now free and clear for their use, no one at Lucasfilm Games saw any reason to assume so.

It was at this juncture that Hal Barwood entered the picture, interested in trying a new career in games on for size. Just about any developer in the industry would have jumped at the chance to bring someone like him aboard. Talk of a merger of games with cinema to create a whole new genre of mass-media entertainment — the interactive movie, preferably published on CD-ROM complete with voice acting and perhaps even real-world video footage — dominated games-industry conferences and magazine editorials alike as the 1990s began. But for all their grandiose talk, the game developers clustered in Northern California were all too aware that they lacked the artistic respectability necessary to tempt most of those working with traditional film and video in the southern part of the state into working with them on interactive projects. Hal Barwood might have been no more than a mid-tier Hollywood player at best, but suffice to say that there wasn’t exactly a surfeit of other Hollywood veterans of any stripe who were willing to work on games.

In an online CompuServe conference involving many prominent adventure-game designers that was held on August 24, 1990, not long after Barwood’s arrival at Lucasfilm Games, Noah Falstein could hardly keep himself from openly taunting his competitors about what he had and they didn’t:

One way we’re trying to incorporate real stories into games is to use real storytellers. Next year, we have a game coming out by Hal Barwood, who’s been a successful screenwriter, director, and producer for years. His most well-known movies probably are the un-credited work he did on Close Encounters and Dragonslayer, which he co-wrote and produced. He’s also programmed his own Apple II games in 6502 assembly in his spare time. I’ve already learned a great deal about pacing, tension, character, and other “basic” techniques that come naturally — or seem to — to him. I highly recommend such collaborations to you all. I think we’ve got a game with a new level of story on the way.

Falstein was in a position to learn so much from Barwood because he had been assigned to work with him as his design partner on his first project — the idea being that Barwood would take care of all the “basic” cinematic techniques Falstein enthuses about above, while Falstein would keep the project on track and make sure it worked as a playable adventure game, with soluble puzzles and all the rest.

Ironically given what Raiders of the Lost Ark had done to Dragonslayer, Hal Barwood’s one big chance to become a truly major Hollywood player, the game in question was to be another Indiana Jones game — albeit one with an original story, not bound to any movie. The initial plan had been to sift through the pile of rejected scripts for the third Indiana Jones film and select a likely candidate from them for adaptation into a game. But it turned out that the scripts were all pretty bad, or at least not terribly suitable for interactive adaptation.

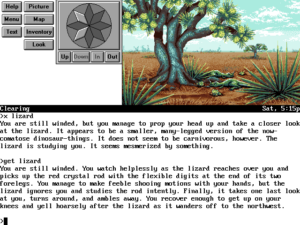

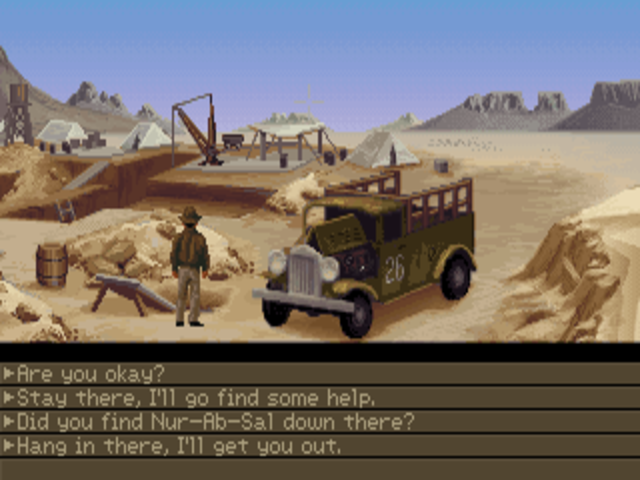

The Azores is one of the many exotic locations Indy visits in Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, all of which are brought to life with aplomb by Lucasfilm Games’s accomplished art team.

So, Barwood and Falstein decided to invent their own story, and thus went looking for legends of lost civilizations that might be worthy of an intrepid archeologist who had already found the Lost Ark of the Covenant and the Holy Grail. “George [Lucas] has established a criterion for Indiana Jones adventures,” said Barwood, “and it’s basically that he should only find things that actually existed — or at least could have existed.” The fabled sunken island of Atlantis seemed the right mixture of myth and history. Barwood:

Our eyes fell upon Atlantis because not only is it an ancient myth known by almost everyone, but it also has wonderful credentials, in that it was first mentioned by Plato a couple thousand years ago. In addition to that, in the early part of this century, the idea was taken over by spiritualists and mystics, who attributed to the Atlanteans this fantastic technology, with airships flying 100 milers per hour, powered by vrill and firestone. When we found this out, we thought to ourselves, “Does this sound as interesting as the Holy Grail? Yes, it does.” Even though it’s a myth, the myth is grounded in a wonderful collection of lore.

The legend’s wide-ranging wellsprings would allow them to send Indy traipsing between exotic locations scattered over much of the world: New York City, Iceland, Guatemala, the Azores, Algiers, Monte Carlo, Crete, Santorini, finally ending up under the ocean at the site of Atlantis itself.

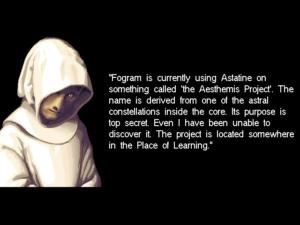

The game known as Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis hits all the notes familiar to anyone who has seen an Indiana Jones film. It seems that the mythical Atlanteans were quite a clever lot, having harnessed energies inconceivable to modern scientists. The Nazis have gotten wind of this, and are fast piecing together the clues that will let them find the undersea site of Atlantis, enter it, and take the technology for themselves, thereby to conquer the world. It’s a fine premise for a globetrotting story of thrills and spills — silly but no more silly than any of those that got made into movies. There’s even a female sparring partner/love interest for Indy, just like in the films. This time her name is Sophia, and she’s a former archaeologist who’s become a professional psychic, much to the scientific-minded Indy’s dismay. Let the battle of barbs begin!

Barwood’s first interactive script really is a good one, with deftly drawn plot beats and characters that, if not exactly deep, nobly fulfill their genre-story purposes as engines of action, tension, or comic relief. Other game writers of the early 1990s weren’t always or even usually all that adept at such basic techniques of fiction as “pacing, tension, and character.” To see how painful a game can be that wants to be like the Indiana Jones movies but lacks the writers to pull it off, one need look no further than Dynamix’s Heart of China, with its humor that lands with the most leaden of thuds, its hero who wants to be a charming rogue but misplaced his charm, and its dull supporting characters who are little more than crude ethnic stereotypes. When you play Fate of Atlantis, by contrast, you feel yourself to be in the hands of a writer who knows exactly what he’s doing.

That said, the degree to which Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is truly cinematic can be and too often is overstated. Games are not movies — an obvious point that game developers of the early 1990s frequently lost sight of in their rush to make their interactive movies. Hal Barwood, the Hollywood veteran brought into Lucasfilm Games to apply his cinematic expertise, was ironically far more aware of this fact than were many other game designers who lacked his experience in the medium they were all so eager to ape. Speaking to the science-fiction writer and frequent games-industry commentator Orson Scott Card in 1990, Barwood made some telling observations:

“The companies making animated games keep talking as if games resembled movies,” he [Barwood] said. “But they don’t resemble movies all that much.”

He granted some resemblances, of course, especially with animated film. The dependence on artists; the trickle rate of production, where you’re producing the game or film at the rate of only minutes, or even seconds, of usable footage a day; and the dominant role of the editing process.

Still, though, when it comes to the art of composing a game, inventing it, he said, “What it really resembles is theater. Plays.”

Why? Because as with a play, you have only a few settings you can work with, and they can usually be viewed from only a single angle and at the same distance. You can’t do any meaningful work with closeups (to design and program genuine realistic facial expressions just isn’t worth the huge investment in time and disk space). It’s so hard to make actions clear that you must either rely on dialogue, like most plays, or show only the simplest, most obvious actions.

In movies, it’s just the opposite. You control the pace and rhythm of film by cutting and shifting the action from place to place. The camera never gazes at any one thing for long.

The computer games of this era which most clearly did understand the kinetic language of cinema — the language of a roving camera and a keen-eyed editor — weren’t any of the avowed interactive movies that were being presented in the form of plot- and dialog-heavy adventure games, but rather the comparatively minimalist action games Prince of Persia and Another World, both essentially one-man productions that employed few to no words. Both of these games were aesthetically masterful, but somewhat more problematic in terms of providing their players with interesting forms of interactivity, thus inadvertently illustrating some of the drawbacks of fetishizing movies as the ideal aesthetic model for games.

All the other people who thought they were making interactive movies were “filming” their productions the way only the very earliest movie directors had filmed, before a proper language of film had been created: through a single static “camera.” The end results were anything but cinematic in the way a fellow like Hal Barwood, steeped throughout his life in the language of film, understood that term. His long experience in film-making allowed him to see the essential fact that games were not movies. They might borrow the occasional technique from cinema, but games were a medium — or, perhaps better stated, a matrix of mediums, only one of which was the point-and-click adventure game — with their own unique sets of aesthetic affordances. Countless game developers seemed to be using the term “interactive movie” to designate any game that had a lot of story, but the qualities of being cinematic and being narrative-oriented were really orthogonal to one another.

In later years, Hal Barwood would describe a narrative-driven game as more akin to a vintage Russian novel than a movie, a “continuous experience in a fictional world”: something the player lives with over a period of days or weeks, working through it at her own pace, mulling it over even when she isn’t actively sitting in front of the computer. The control or lack thereof of pacing is a critical distinction: a game which leaves any reasonable scope of agency to its player must necessarily cede much or all of the control of pacing to her. And yet pacing is absolutely key to the final effect of any movie, so much so that the director may very well spend months in the editing room after all the shooting is done, trying to get the pacing just right. The game designer doesn’t have anything like the same measure of direct control over the player’s experience, and so must deliver a very different sort of fiction.

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis works because it understands these differences in media. It plays with the settings, characters, and themes of the Indiana Jones movies to fine effect, but never forgets that it’s an adventure game. The driving mechanic of an adventure game — the solving of intellectual puzzles — is quite distinct from that which drives the movies, and the plot points must be adapted to match. Can you imagine the cinematic Indy sticking wads of chewing gum to the soles of his shoes so as to climb up a coal chute? Or using a bathroom plunger as a handy replacement for a missing control lever inside a Nazi submarine? Puzzles of this nature inevitably make Indy himself into a rather different sort of personality — one a little less cool and collected, a little more prone to be the butt of the joke rather than the source of it. It’s clear from the very opening scenes of Fate of Atlantis, an innovative interactive credits sequence in which poor Indy must endure pratfall after pratfall, that this isn’t quite the same character we thrilled to in the movies. Harrison Ford would have walked out if asked to play a series of scenes like these.

This phenomenon, which we might call the Guybrush Threepwoodization of the hero, is very common in adventure games adapted from other media, given that the point-and-click adventure game as a medium wants always to collapse back into comedy as its default setting. (See, for example, the Neuromancer game, which similarly turns the cool cat Case from its source novel into a put-upon loser, and winds up becoming a pretty great game in the process.) Barwood and Falstein as well decided that Indiana Jones must adapt to the adventure-game genre rather than the adventure-game genre adapting to Indiana Jones. This was most definitely the right approach to take, and is the overarching reason why this game succeeds when so many other interactive adaptations fail.

The one place where the otherwise traditionalist Fate of Atlantis clearly does try to do something new has nothing directly to do with its source material. It rather takes the form of three possible narrative through lines, depending on the player’s individual predilections. After playing through the introductory stages of the game, you’re given a choice between a “Team” path, where Indy and Sophia travel together and cooperate to solve problems; a “Wits” path, where Indy travels largely alone and solves problems using his noggin; and a “Fists” path, where Indy travels alone and solves some though by no means all of his problems using more, shall we say, active measures, which translate into little action-oriented minigames for the player. The last is seemingly the closest to the spirit of the films, but is, tellingly, almost universally agreed to be the least interesting way to play the game.

The Team path, like all of them, has its advantages and disadvantages. It’s great to have Sophia around to help out with things — until she falls down a pit and needs your help getting out.

Although the message would get a little muddled once the game reached stores — “three games in one!” was a tagline few marketers could resist — Barwood and Falstein’s primary motivation in making these separate paths wasn’t to create a more replayable game, but rather a more accessible one. Lucasfilm Games always placed great emphasis on giving their players a positive, non-frustrating experience. Different players would prefer to play in different ways, Barwood and Falstein reasoned, and their game should adapt to that. “Socially-oriented” players — possibly including the female players they were always hoping to reach — would enjoy the Team path with its constant banter and pronounced romantic tension between Indy and Sophia; the stereotypically hardcore, cerebral adventure gamers would enjoy the Wits path; those who just wanted to get through the story and check out all the exotic destinations could go for the Fists path.

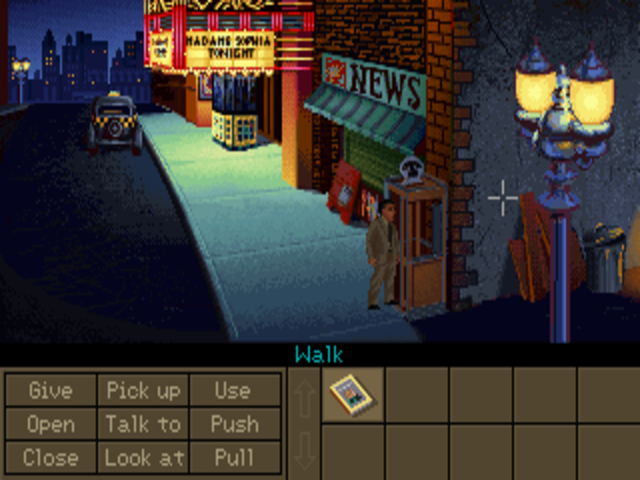

Falstein liked to call Fate of Atlantis a “self-tuning game.” In this spirit, until very late in development the branching pathways were presented not as an explicit choice but rather as a more subtle in-game personality test. Early on, Indy needs to get into a theater even though he doesn’t have a ticket. There are three ways to accomplish this: talking his way past the guard at the door; puzzling his way through a maze of boxes to find a hidden fire-escape ladder; or simply sucker-punching the guard. Thus would the player’s predilections be determined. In the interest of transparency and as a sop to replayability, however, the personality test wound up being replaced by a simple menu for choosing your pathway.

The first substantial interactive scene in the game, taking place outside and inside a theater in New York City where Indy’s adventuring partner-to-be Sophia is giving a lecture, was intended to function as a personality test of sorts, determining whether the player was sent down the Team, Wits, or Fists path. In the end, though, its findings were softened to a mere recommendation preceding an explicit choice of paths which is offered to the player at its conclusion.

The idea of multiple pathways turned out not to be as compelling in practice as in theory. Most players did take it more as an invitation to play the game three times than an opportunity to play it once their way, and were disappointed to discover that the branching pathways encompass only about 60 percent of the game as a whole; the first 10 percent or so, as well as the lengthy climax, are the same no matter which pathway you choose. Nor are the Team and Wits pathways different enough from one another to give the game all that much of a different flavor; they both ultimately come down to solving a series of logic puzzles. The designers’ time would probably have been better spent making one pathway through the game that combined elements of the Team and Wits pathways. Lucasfilm Games never tried anything similar again. The branching pathways were an experiment, and in that sense at least they served their purpose.

A substantial but by no means enormous game, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis nevertheless spent some two years in development, a lengthy span of time indeed by the standards of the early 1990s, being at least three times as long as it had taken to make the Last Crusade game. The protracted development cycle wasn’t a symptom of acrimony, lack of focus, or disorganization, as such things so often tend to be. It was rather a byproduct of the three pathways and, most of all, of Lucasfilm Games’s steadfast commitment to getting everything right, prioritizing quality and polish over release dates in that way that always set them apart from the majority of their peers.

Shortly before the belated release of Fate of Atlantis in the summer of 1992, Lucasfilm Games became LucasArts. The slicker, less subservient appellation was a sign of their rising status within the hierarchy of their parent company, as their games sold in bigger quantities and became a substantial revenue stream in their own right, less and less dwarfed by the money that could be made in movies. Those changing circumstances would prove a not-unmixed blessing for them, forcing them to move out of the rustic environs of Skywalker Ranch and shed much of the personality of a quirky artists’ collective for that of a more hard-nosed media enterprise. On the other hand, at least they’d finally get to make Star Wars games…

But that’s an article for another day. I should conclude this one by noting that Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis [2]Once again, there was also a Fate of Atlantis action game, made in Britain with a particular eye to the 8-bit machines in Europe which couldn’t run the adventure game. And once again, it garnered little attention in comparison to its big brother. was greeted with superlative reviews and equally strong sales; even Steven Spielberg, who unlike his friend George Lucas was a big fan of games, played through it and reportedly enjoyed it very much. A year after the original floppy-disk-based release, LucasArts made a “talkie” version for CD-ROM. Getting Harrison Ford to play Indiana Jones was, as you might imagine, out of the question, but they found a credible soundalike, and handled the voice acting as a whole with their usual commitment to quality, recruiting professional voice talent in Hollywood and recording them in the state-of-the-art facilities of Skywalker Sound.

While hard sales numbers for LucasArts’s adventure games have never surfaced to my knowledge, Noah Falstein claims that Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis sold the most of all of them — a claim I can easily imagine to be correct, given its rapturous critical reception and the intrinsic appeal of its license. Today, it tends to be placed just half a step down from the most-loved of the LucasArts adventures, lacking perhaps some of the manic inspiration of the studio’s completely original creations. Nonetheless, it’s a fine, fine game, well worth playing through twice or thrice — at least its middle section, where the pathways diverge — to experience all it has to offer. This game adapted from a movie franchise, which succeeds by not trying to be a movie, marked a fine start for Hal Barwood’s new career.

(Sources: the books The Secret History of Star Wars by Michael Kaminski and Droidmaker: George Lucas and the Digital Revolution by Michael Rubin; LucasArts’s Adventurer magazine of Fall 1991, Spring 1992, and Spring 1993; Starlog of July 1981, September 1981, August 1982, May 1985, September 1985, November 1985, December 1985, and February 1988; Amiga Format of February 1992; Compute! of February 1991; Computer Gaming World of September 1992; CU Amiga of June 1992; Electronic Games of October 1992; MacWorld of June 1989; Next Generation of October 1998; PC Review of September 1992; PC Zone of January 2000; Questbusters of September 1992; Zero of August 1991 and March 1992. Online sources include Arcade Attack‘s interviews with Noah Falstein and Hal Barwood; Noah Falstein’s Reddit AMA; MCV‘s articles on “The Early Days of LucasArts”; Noah Falstein’s presentation on LucasArts at Øredev 2017.

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is available for purchase on GOG.com.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | An Action Game was also published under the auspices of Lucasfilm Games, but its development was outsourced to a British house. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Once again, there was also a Fate of Atlantis action game, made in Britain with a particular eye to the 8-bit machines in Europe which couldn’t run the adventure game. And once again, it garnered little attention in comparison to its big brother. |