It says much about Sid Meier, a born game designer if ever there was one, that he tended to get some of his best work done when he was allegedly on vacation. A few years after his significant other had lost all track of him on what she thought was a romantic getaway to the Caribbean but he came to see as the ideal chance to research his game Pirates!, another opportunity for couple time went awry in August of 1989, when he spent the entirety of a beach holiday coding a game about railroads on the computer he’d lugged with him. The experience may not have done his relationship any favors, but he did come home with the core of his second masterpiece of a game — a game that would usher in what many old-timers still regard as the golden age of computerized grand strategy.

That Meier felt empowered to spend so much time on a game that featured no war or killing says much about the changing times inside MicroProse, the erstwhile specialist in military simulations and war games he had co-founded with the flamboyant former active-duty Air Force pilot “Wild” Bill Stealey. The first great deviation from the norm for MicroProse had been Meier’s first masterpiece, the aforementioned Pirates! of 1987, which Stealey had somewhat begrudgingly allowed him to make as a palate cleanser between the company’s military games. After that, it had been back to business as usual for a while, with Meier designing a submarine simulator based on a Tom Clancy thriller (the audience synergy of that project was almost too perfect to be believed) and then a flight simulator based on the rampant speculation among aviation buffs about the Air Force’s cutting-edge new stealth fighter (the speculation would almost all prove to be incorrect when the actual stealth fighter was unveiled, leaving MicroProse with a “simulation” of an airplane that had never existed).

Yet by the time the latter game was nearing completion in late 1988, a couple of things were getting hard to ignore. First was the warm reception that had been accorded to Pirates!, the way that entirely new demographics of players who would never have dreamed of buying any of MicroProse’s other games were buying and enjoying this one. And second was the fact that the market for MicroProse’s traditional military simulations, while it had served them well — in fact, served them to the tune of nearly 1 million copies sold of their most successful simulation of all, Sid Meier’s F-15 Strike Eagle — was starting to show signs of having reached its natural limit. If, in other words, MicroProse hoped to continue to increase their sales each year — something the aggressive and ambitious Stealey liked doing even more than he liked making and flying flight simulators — they were going to have to push outside of Stealey’s comfort zone. Accordingly, MicroProse dramatically expanded the scope of their business in the last two years of the 1980s, buying the Firebird and Rainbird software labels from British Telecom and setting up an affiliated-label program for distributing the work of smaller publishers; Stealey hoped the latter might come in time to rival the similar programs of Electronic Arts and Activision/Mediagenic. In terms of in-house development, meanwhile, MicroProse went from all military games all the time — apart from, that is, the aberration that had been Pirates! — to a half-and-half mixture of games in the old style and games that roamed further afield, in some cases right into the sweet spot that had yielded the big hit Pirates!.

Thus the first project which Sid Meier took up after finishing F-19 Stealth Fighter was a spy game called Covert Action. Made up like Pirates! of a collection of mini-games, Covert Action was very much in the spirit of that earlier game, but had been abandoned by its original designer Lawrence Schick as unworkable. Perhaps because of its similarities to his own earlier game, Meier thought he could make something out of it, especially if he moved it from the Commodore 64 to MS-DOS, which had become his new development platform with F-19 Stealth Fighter. But Covert Action proved to be one of those frustrating games that just refused to come together, even in the hands of a designer as brilliant as Meier. He therefore started spending more and more of the time he should have been spending on Covert Action tinkering with ideas and prototypes for other games. In the spring of 1989, he coded up a little simulation of a model railroad.

The first person to whom Meier showed his railroad game was Bruce Shelley, his “assistant” at MicroProse and, one senses, something of his protege, to whatever extent a man as quiet and self-effacing as Meier was can be pictured to have cultivated someone for such a role. Prior to coming to MicroProse, Shelley had spent his first six years or so out of university at Avalon Hill, the faded king of the previous decade’s halcyon years of American tabletop war-gaming. MicroProse had for some time been in the habit of hiring refugees from the troubled tabletop world, among them Arnold Hendrick and the aforementioned Lawrence Schick, but Shelley was hardly one of the more illustrious names among this bunch. Working as an administrator and producer at Avalon Hill, he’d had the opportunity to streamline plenty of the games the company had published during his tenure, but had been credited with only one original design of his own, a solitaire game called Patton’s Best. When he arrived at MicroProse in early 1988 — he says his application for employment there was motivated largely by the experience of playing Pirates! — Shelley was assigned to fairly menial tasks, like creating the maps for F-19 Stealth Fighter. Yet something about him clearly impressed Sid Meier. Shortly after F-19 Stealth Fighter was completed, Meier came to Shelley to ask if he’d like to become his assistant. Shelley certainly didn’t need to be asked twice. “Anybody in that office would have died for that position,” he remembers.

Much of Shelley’s role as Meier’s assistant, especially in the early days, entailed being a constantly available sounding board, playing with the steady stream of game prototypes Meier gave to him — Meier always seemed to have at least half a dozen such potential projects sitting on his hard drive alongside whatever project he was officially working on — and offering feedback. It was in this capacity that Shelley first saw the model-railroad simulation, whereupon it was immediately clear to him that this particular prototype was something special, that Meier was really on to something this time. Such was Shelley’s excitement, enthusiasm, and insightfulness that it wouldn’t take long for him to move from the role of Meier’s sounding board to that of his full-fledged co-designer on the railroad game, even as it always remained clear who would get to make the final decision on any question of design and whose name would ultimately grace the box.

It appears to have been Shelley who first discovered Will Wright’s landmark city simulation SimCity. Among the many possibilities it offered was the opportunity to add a light-rail system to your city and watch the little trains driving around; this struck Shelley as almost uncannily similar to Meier’s model railroad. He soon introduced Meier to SimCity, whereupon it became a major influence on the project. The commercial success of SimCity had proved that there was a place in the market for software toys without much of a competitive element, a description which applied perfectly to Meier’s model-railroad simulation at the time. “Yes, there is an audience out there for games that have a creative aspect to them,” Meier remembers thinking. “Building a railroad is something that can really emphasize that creative aspect in a game.”

And yet Meier and Shelley weren’t really happy with the idea of just making another software toy, however neat it was to lay down track and flip signals and watch the little trains drive around. Although both men had initially been wowed by SimCity, they both came to find it a little unsatisfying in the end, a little sterile in its complete lack of an historical context to latch onto or goals to achieve beyond those the player set for herself. At times the program evinced too much fascination with its own opaque inner workings, as opposed to what the player was doing in front of the screen. As part of his design process, Meier likes to ask whether the player is having the fun or whether the computer — or, perhaps better said, the game’s designer — is having the fun. With SimCity, it too often felt like the latter.

In his role as assistant, Shelley wrote what he remembers as a five- or six-page document that outlined a game that he and Meier were calling at that time The Golden Age of Railroads; before release the name would be shortened to the pithier, punchier Railroad Tycoon. Shelley expressed in the document their firm belief that they could and should incorporate elements of a software toy or “god game” into their creation, but that they wanted to make more of a real game out of it than SimCity had been, wanted to provide an economic and competitive motivation for building an efficient railroad. Thus already by this early stage the lines separating a simulation of real trains from one of toy trains were becoming blurred.

Then in August came that fateful beach holiday which Meier devoted to Railroad Tycoon. Over the course of three weeks of supposed fun in the sun, he added to his model-railroad simulation a landscape on which one built the tracks and stations. The landscape came complete with resources that needed to be hauled from place to place, often to be converted into other resources and hauled still further: trains might haul coal from a coal mine to a steel mill, carry the steel that resulted to a factory to be converted into manufactured goods, then carry the manufactured goods on to consumers in a city. When Meier returned from holiday and showed it to him, Shelley found the new prototype, incorporating some ideas from his own recent design document and some new ones of Meier’s making, to be just about the coolest thing he’d ever seen on a computer screen. Shelley:

We went to lunch together, and he said, “We have to make a decision about whether we’re going to do this railroad game or whether we’re going to do the spy game.”

I said, “If you’re asking me, there’s no contest. We’re doing the railroad game. It’s really cool. It’s so much fun. I have zero weight in this company. I don’t have a vote in any meeting. It’s up to you, but I’m ready to go.”

Shelley was so excited by the game that at one point he offered to work on it for free after hours if that was the only way to get it done. Thankfully, it never came to that.

Dropping Covert Action, which had already eaten up a lot of time and resources, generated considerable tension with Stealey, but when it came down to it it was difficult for him to say no to his co-founder and star designer, the only person at the company who got his name in big letters on the fronts of the boxes. (Stealey, who had invented the tactic of prefixing “Sid Meier’s” to Meier’s games as a way of selling the mold-busting Pirates!, was perhaps by this point wondering what it was he had wrought.) The polite fiction which would be invented for public consumption had it that Meier shifted to Railroad Tycoon while the art department created the graphics for Covert Action. In reality, though, he just wanted to escape a game that refused to come together in favor of one that seemed to have all the potential in the world.

Meier and Shelley threw themselves into Railroad Tycoon. When not planning, coding — this was strictly left to Meier, as Shelley was a non-programmer — or playing the game, they were immersing themselves in the lore and legends of railroading: reading books, visiting museums, taking rides on historic steam trains. The Baltimore area, where MicroProse’s offices were located, is a hotbed of railroad history, being the home of the legendary Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the oldest common-carrier rail network in the country. Thus there was plenty in the area for a couple of railroad buffs to see and do. Meier and Shelley lived and breathed trains for a concentrated six months, during which they, in tandem with a few artists and other support personnel, took Railroad Tycoon from that August prototype to the finished, boxed game that shipped to stores in April of 1990, complete with a beefy 180-page manual written by Shelley. Leaving aside all of Railroad Tycoon‘s other merits, it was a rather breathtaking achievement just to have created a game of such ambition and complexity in such a short length of time.

But even in ways apart from its compressed development time Railroad Tycoon is far more successful than it has any right to be. It’s marked by a persistent, never entirely resolved tension — one might even say an identity crisis — between two very different visions of what a railroad game should be. To say that one vision was primarily that of Meier and the other that of Shelley is undoubtedly a vast oversimplification, but is nevertheless perhaps a good starting point for discussion.

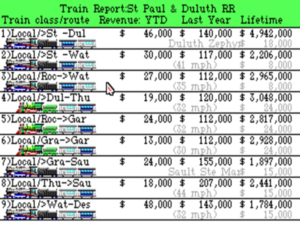

One vision of Railroad Tycoon is what we might call the operational game, the building game, or the SimCity-like game, consisting of laying down stations, tracks, and switches, scheduling your trains, and watching over them as they run in real time. A certain kind of player can spend hours tinkering here, trying always to set up the most efficient possible routes, overriding switches on the fly to push priority cargoes through to their destinations for lucrative but intensely time-sensitive rewards. None of this is without risk: if you don’t do things correctly, trains can hurtle into one another, tumble off of washed-out bridges, or just wind up costing you more money than they earn. It’s therein, of course, where the challenge lies. This is Meier’s vision of Railroad Tycoon, still rooted in the model-railroad simulation he first showed Shelley back in early 1989.

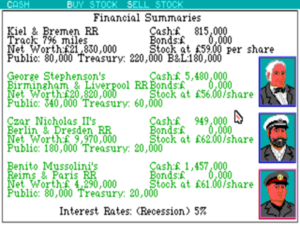

The other vision of Railroad Tycoon is the game of high-level economic strategy, which first began to assert itself in that design document Bruce Shelley wrote up in mid-1989. In addition to needing to set up profitable routes and keep an eye on your expenses, you also need to judge when to sell bonds to fund expansion and when to buy them back to save the interest payments, when to buy and sell your own stock and that of other railroads to maximize your cash reserves. Most of all, you need to keep a close eye on the competition, who, if you’ve turned the “cutthroat competition” setting on, will try to buy your railroad out from under you by making runs on your stock — that is, when they aren’t building track into your stations, setting up winner-take-all “rate wars.”

This vision of Railroad Tycoon owes much to a board game called 1830: Railways and Robber Barons which Shelley had shepherded through production during his time at Avalon Hill. Although that game was officially designed by Francis Tresham, Shelley had done much to help turn it into the classic many board-game connoisseurs still regard it as today. After Shelley had arrived at MicroProse with his copy of 1830 in tow, it had become a great favorite during the company’s occasional board-game nights. While 1830 traded on the iconography of the Age of Steam, it was really a game of stock-market manipulation; the railroads in the game could have been swapped out for just about any moneymaking industry.

Put very crudely, then, Railroad Tycoon can be seen as 1830 with a SimCity-like railroad simulation grafted on in place of the board game’s pure abstractions. Bill Stealey claims that Eric Dott, the president of Avalon Hill, actually called him after Railroad Tycoon‘s release to complain that “you’re doing my board game as a computer game.” Stealey managed to smooth the issue over; “well, don’t let it happen again” were Dott’s parting words. (This would become a problem when Meier and Shelley promptly did do it again, creating a computer game called Civilization that shared a name as well as other marked similarities with the Avalon Hill board game Civilization.)

Immense though its influence was, some of the elements of 1830 came to Railroad Tycoon shockingly late. Meier insists, for instance, that the three computerized robber barons you compete against were coded up in a mad frenzy over the last two weeks before the game had to ship. Again, it’s remarkable that Railroad Tycoon works at all, much less works as well as it does.

The problem of reconciling the two halves of Railroad Tycoon might have seemed intractable to many a design team. Consider the question of time. The operational game would seemingly need to run on a scale of days and hours, as trains chug around the tracks picking up and delivering constant streams of cargo. Yet the high-level economic game needs to run on a scale of months and years. A full game of Railroad Tycoon lasts a full century, over the course of which Big Changes happen on a scale about a million miles removed from the progress of individual trains down the tracks: the economy booms and crashes and booms again; coal and oil deposits are discovered and exploited and exhausted; cities grow; new industries develop; the Age of Steam gives ways to the Age of Diesel; competitors rise and fall and rise again. “You can’t have a game that lasts a hundred years and be running individual trains,” thought Meier and Shelley initially. If they tried to run the whole thing at the natural scale of the operational game, they’d wind up with a game that took a year or two of real-world time to play and left the player so lost in the weeds of day-to-day railroad operations that the bigger economic picture would get lost entirely.

Meier’s audacious solution was to do the opposite, to run the game as a whole at the macro scale of the economic game. This means that, at the beginning of the game when locomotives are weak and slow, it might take six months for a train to go from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. What ought to be one day of train traffic takes two years in the game’s reckoning of time. As a simulation, it’s ridiculous, but if we’re willing to see each train driving on the map as an abstraction representing many individual trains — or, for that matter, if we’re willing to not think about it at all too closely — it works perfectly well. Meier understood that a game doesn’t need to be a literal simulation of its subject to evoke the spirit of its subject — that experiential gaming encompasses more than simulations. Railroad Tycoon is, to use the words of game designer Michael Bate, an “aesthetic simulation” of railroad history.

Different players inevitably favor different sides of Railroad Tycoon‘s personality. When I played the game again for the first time in a very long time a year or so ago, I did so with my wife Dorte. Wanting to take things easy our first time out, we played without cutthroat competition turned on, in which mode the other railroads just do their own thing without actively trying to screw with your own efforts. Dorte loved designing track layouts and setting up chains of cargo deliveries for maximum efficiency; the process struck her, an inveterate puzzler, as the most delightful of puzzles. After we finished that game and I suggested we play again with cutthroat competition turned on, explaining how it would lead to a much more, well, cutthroat economic war, she said that the idea had no appeal whatsoever for her. Thus was I forced to continue my explorations of Railroad Tycoon on my own. The game designer Soren Johnson, by contrast, has told in his podcast Designer Notes how uninterested he was in the operational game, preferring to just spend some extra money to double-track everything and as much as possible forget it existed. It was rather the grand strategic picture that interested him. As for me, wishy-washy character that I am, I’m somewhere in the middle of these two extremes.

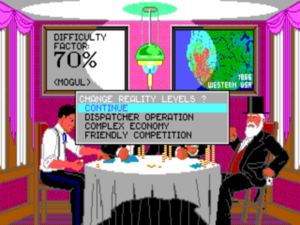

One of the overarching themes of Sid Meier’s history as a game designer is a spirit of generosity, a willingness to let his players play their way. Railroad Tycoon provides a wonderful example in the lengths to which it goes to accommodate the Dortes, the Sorens, and the Jimmys. If you want to concentrate on the operational game, you can turn off cutthroat competition, turn on “dispatcher operations,” set the overall difficulty to its lowest level so that money is relatively plentiful, and have at it. If even that winds up entailing more economics than you’d like to concern yourself with, one of Railroad Tycoon‘s worst-kept secrets is an “embezzlement key” that can provide limitless amounts of cash, allowing you essentially to play it as the model-railroad simulation that it was at its genesis. If, on the other hand, you’re interested in Railroad Tycoon primarily as a game of grand economic strategy, you can turn on cutthroat competition, turn off dispatcher operations, crank the difficulty level up, and have a full-on business war that would warm the cockles of Jack Tramiel’s heart. If you’re a balanced (or wishy-washy) fellow like me, you can turn on cutthroat competition and dispatcher operations and enjoy the full monty. Meier and Shelley added something called priority shipments to the game — one-time, extremely lucrative deliveries from one station to another — to give players like me a reason to engage with the operational game even after their tracks and routes are largely set. Priority deliveries let you earn a nice bonus by manually flipping signals and shepherding a train along — but, again, only if you enjoy that sort of thing; a budding George Soros can earn as much or more by playing the stock market just right.

One story from Railroad Tycoon‘s development says much about Sid Meier’s generous spirit. Through very nearly the entirety of the game’s development, Meier and Shelley had planned to limit the amount of time you could play at the lower difficulty levels as a way of rewarding players who were willing to tackle the challenge of the higher levels. Such a restriction meant not only that players playing at the lower difficulty levels had less time to build their railroad network, but that they lost the chance to play with the most advanced locomotives, which only become available late in the game. Almost literally at the very last possible instant, Meier decided to nix that scheme, to allow all players to play for the full 100 years. Surely fans of the operational game should have access to the cool later trains as well. After all, these were the very people who would be most excited by them. The change came so late that the manual describes the old scheme and the in-game text also is often confused about how long you’re actually going to be allowed to play. It was a small price to pay for a decision that no one ever regretted.

That said, Railroad Tycoon does have lots of rough edges like this confusion over how long you’re allowed to play, an obvious byproduct of its compressed development cycle. Meier and Shelley and their playtesters had nowhere near enough time to make the game air-tight; there are heaps of exploits big enough to drive a Mallet locomotive through (trust me, that’s a big one!). It didn’t take players long to learn that they could wall off competing railroads behind cages of otherwise unused track and run wild in virgin territory on their own; that they could trick their competitors into building in the most unfavorable region of the map by starting to build there themselves, then tearing up their track and starting over competition-free in better territory; that the best way to make a lot of money was to haul nothing but passengers and mail, ignoring all of the intricacies of hauling resources that turned into other resources that turned into still other resources; that they could do surprisingly well barely running any trains at all, just by playing the market, buying and selling their competitors’ stock; that they could play as a real-estate instead of a railroad tycoon, buying up a bunch of land during economic panics by laying down track they never intended to use, then selling it again for a profit during boom times by tearing up the track. Yes, all of these exploits and many more are possible — and yes, the line between exploits and ruthless strategy is a little blurred in many of these cases. But it’s a testament to the core appeal of the game that, after you get over that smug a-ha! moment of figuring out that they’re possible, you don’t really want to use them all that much. The journey is more important than the destination; something about Railroad Tycoon makes you want to play it fair and square. You don’t even mind overmuch that your computerized competitors get to play a completely different and, one senses, a far easier game than the one you’re playing. They’re able to build track in useful configurations that aren’t allowed to you, and they don’t even have to run their own trains; all that business about signals and congestion and locomotives gets abstracted away for them.

Despite it all, I’m tempted to say that in terms of pure design Railroad Tycoon is actually a better game than Civilization, the game Meier and Shelley would make next and the one which will, admittedly for some very good reasons, always remain the heart of Meier’s legacy as a designer. Yet it’s Railroad Tycoon that strikes me as the more intuitive, playable game, free of the tedious micromanagement that tends to dog Civilization in its latter stages. Likewise absent in Railroad Tycoon is the long anticlimax of so many games of Civilization, when you know you’ve won but still have to spend hours mopping up the map before you can get the computer to recognize it. Railroad Tycoon benefits enormously from its strict 100-year time limit, as it does from the restriction of your railroad, born from technical limitations, to 32 trains and 32 stations. “You don’t need more than that to make the game interesting,” said Meier, correctly. And, whereas the turn-based Civilization feels rather like a board game running on the computer, the pausable real time of Railroad Tycoon makes it feel like a true born-digital creation.

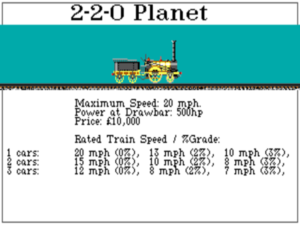

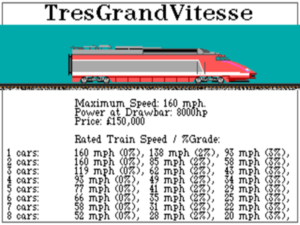

Of course, mechanics and interface are far from the sum total of most computer games, and it’s in the contextual layer that Civilization thrives as an experiential game, as an awe-inspiring attempt to capture the sum total of human thought and history in 640 K of memory. But, having said that, I must also say that Railroad Tycoon is itself no slouch in this department. It shows almost as beautifully as Civilization how the stuff of history can thoroughly inform a game that isn’t trying to be a strict simulation of said history. From the manual to the game itself, Railroad Tycoon oozes with a love of trains. To their credit, Meier and Shelley don’t restrict themselves to the American Age of Steam, but also offer maps of Britain and continental Europe on which to play, each with its own challenges in terms of terrain and economy. The four available maps each have a different starting date, between them covering railroad history from the distant past of 1825 to the at-the-time-of-the-game’s-development near-future of 2000. As you play, new locomotives become available, providing a great picture of the evolution of railroading, from Robert Stephenson’s original 20-horsepower Planet with its top speed of 20 miles per hour to the 8000-horsepower French Train à Grande Vitesse (“high-speed train”) with a top speed of 160 miles per hour. This is very much a trainspotter’s view of railroad history, making no attempt to address the downsides of the rush to bind nations up in webs of steel tracks, nor asking just why the historical personages found in the game came to be known as the robber barons. (For an introduction to the darker side of railroad history, I recommend Frank Norris’s 1901 novel The Octopus.) But Railroad Tycoon isn’t trying to do social commentary; it just revels in a love of trains, and that’s fine. It’s immensely likeable on those terms — another byproduct of the spirit of generosity with which it’s so shot through. Just hearing the introduction’s music makes me happy.

Upon its release, Railroad Tycoon hit with the force of a freight train. Following the implosion of the 8-bit market at the tail end of the 1980s, North American computer gaming had moved upscale to focus on the bigger, more expensive MS-DOS machines and the somewhat older demographic that could afford them. These changes had created a hunger for more complicated, ambitious strategy and simulation games. SimCity had begun to scratch that itch, but its non-competitive nature and that certain sense of sterility that clung to it left it ultimately feeling a little underwhelming for many players, just it as it had for Meier and Shelley. Railroad Tycoon remedied both of those shortcomings with immense charm and panache. Soren Johnson has mentioned on his podcast how extraordinary the game felt upon its release: “There was just nothing like it at the time.” Computer Gaming World, the journal of record for the new breed of older and more affluent computer gamers, lavished Railroad Tycoon with praise, naming it their “Game of the Year” for 1990. Russell Sipe, the founder and editor-in-chief of the magazine, was himself a dedicated trainspotter, and took to the game with particular enthusiasm, writing an entire book about it which spent almost as much time lingering lovingly over railroad lore as it did telling how to win the thing.

Meier and Shelley were so excited by what they had wrought that they charged full steam ahead into a Railroad Tycoon II. But they were soon stopped in their tracks by Bill Stealey, who demanded that they do something with Covert Action, into which, he insisted, MicroProse had poured too many resources to be able to simply abandon it. By the time that Meier and Shelley had done what they could in that quarter, the idea that would become Civilization had come to the fore. Neither designer would ever return to Railroad Tycoon during their remaining time at MicroProse, although some of the ideas they’d had for the sequel, like scenarios set in South America and Africa, would eventually make their way into a modestly enhanced 1993 version of the game called Railroad Tycoon Deluxe.

Coming as it did just before Civilization, the proverbial Big Moment of Sid Meier’s illustrious career, Railroad Tycoon‘s historical legacy has been somewhat obscured by the immense shadow cast by its younger sibling; even Meier sometimes speaks of Railroad Tycoon today in terms of “paving the way for Civilization.” Yet in my view it’s every bit as fine a game, and when all is said and done its influence on later games has been very nearly as great. “At the beginning of the game you had essentially nothing, or two stations and a little piece of track,” says Meier, “and by the end of the game you could look at this massive spiderweb of trains and say, ‘I did that.'” Plenty of later games would be designed to scratch precisely the same itch. Indeed, Railroad Tycoon spawned a whole sub-genre of economic strategy games, the so-called “Tycoon” sub-genre — more often than not that word seems to be included in the games’ names — that persists to this day. Sure, the sub-genre has yielded its share of paint-by-numbers junk, but it’s also yielded its share of classics to stand alongside the original Railroad Tycoon. Certainly it’s hard to imagine such worthy games as Transport Tycoon or RollerCoaster Tycoon — not to mention the post-MicroProse Railroad Tycoon II and 3 — existing without the example provided by Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley.

But you don’t need to look to gaming history for a reason to play the original Railroad Tycoon. Arguably the finest strategy game yet made for a computer in its own time, it must remain high up in that ranking even today.

(Sources: the books Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III, The Official Guide to Sid Meier’s Railroad Tycoon by Russell Sipe, and Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsay; ACE of May 1990; Compute!’s Gazette of May 1989; Computer Gaming World of May 1990, July/August 1990, and September 1990; Soren Johnson’s interviews with Bruce Shelley and Sid Meier. My huge thanks go to Soren for providing me with the raw audio of his Sid Meier interview months before it went up on his site, thus giving me a big leg up on my research.

Railroad Tycoon Deluxe has been available for years for free from 2K Games’s website as a promotion for Meier’s more recent train game Railroads!. It makes a fine choice for playing today. But for anyone wishing to experience the game in its original form, I’ve taken the liberty of putting together a download of the original game, complete with what should be a working DOSBox configuration and some quick instructions on how to get it running.)