One can learn much about the state of computer gaming in any given period by looking to the metaphors its practitioners are embracing. In the early 1980s, when interfaces were entirely textual and graphics crude or nonexistent, text adventures like those of Infocom were heralded as the vanguard of a new interactive literature destined to augment or entirely supersede non-interactive books. That idea peaked with the mid-decade bookware boom, when just about every entertainment-software publisher (and a few traditional book publishers) were rushing to sign established authors and books to interactive projects. It then proceeded to collapse just as quickly under the weight of its own self-importance when the games proved less compelling and the public less interested than anticipated.

Prompted by new machines like the Commodore Amiga with their spectacular graphics and sound, the industry reacted to that failure by turning to the movies for media mentorship. This relationship would prove more long-lasting. By the end of the 1980s, companies like Cinemaware and Sierra were looking forward confidently to a blending of Hollywood and Silicon Valley that they believed might just replace the conventional non-interactive movie, not to mention computer games as people had known them to that point. Soon most of the major publishers would be conducting casting calls and hiring sound stages, trying literally to make games out of films. It was an approach fraught with problems — problems that were only slowly and grudgingly acknowledged by these would-be unifiers of Southern and Northern Californian entertainment. Before it ran its course, it spawned lots of really terrible games (and, it must be admitted, against all the odds the occasional good one as well).

Given the game industry’s growing fixation on the movies as the clock wound down on the 1980s, Jordan Mechner would seem the perfect man for the age. Struggling with the blessing or curse of an equally abiding love for both mediums, his professional life had already been marked by constant vacillation between movies and games. Inevitably, his love of film influenced him even when he was making games. But, perhaps because that love was so deep and genuine, he accomplished the blending in a more even-handed, organic way than would most of the multi-CD, multi-gigabyte interactive movies that would soon be cluttering store shelves. Mechner’s most famous game, by contrast, filled just two Apple II disk sides — less than 300 K in total. And yet the cinematic techniques it employs have far more in common with those found in the games of today than do those of its more literal-minded rivals.

As a boy growing up in the wealthy hamlet of Chappaqua, New York, Jordan Mechner dreamed of becoming “a writer, animator, or filmmaker.” But those ambitions got modified if not discarded when he discovered computers at his high school. Soon after, he got his hands on his own Apple II for the first time. Honing his chops as a programmer, he started contributing occasional columns on BASIC to Creative Computing magazine at the age of just 14. Yet fun as it was to be the magazine’s youngest contributor, his real reason for learning programming was always to make games. “Games were the only kind of software I knew,” he says. “They were the only kind that I enjoyed. At that time, I didn’t really see any use for a word processor or a spreadsheet.” He fell into the throes of what he describes as an “obsession” to get a game of his own published.

Initially, he did what lots of other game programmers were doing at the time: cloning the big standup-arcade hits for fun and (hopefully) profit. He made a letter-perfect copy of Atari’s Asteroids, changed the titular space rocks to bright bouncing balls in the interest of plausible deniability, and sent the resulting Deathbounce off to Brøderbund for consideration; what with Brøderbund having been largely built on the back of Apple Galaxian, an arcade clone which made no effort whatsoever to conceal its source material, the publisher seemed a very logical choice. But Doug Carlston was now trying to distance his company from such fare for reasons of reputation as well as his fear of Atari’s increasingly aggressive legal threats. Nice guy that he was, he called Mechner personally to explain why Deathbounce wasn’t for Brøderbund. He promised to send Mechner a free copy of Brøderbund’s latest hit, Choplifter, suggesting he think about whether he might be able to apply the programming chops he had demonstrated in Deathbounce to a more original game, as Choplifter‘s creator Dan Gorlin had done. Mechner remembers the conversation as well-nigh life-changing. He had been so immersed in the programming side of making games that the idea of doing an original design had never really occurred to him before: “I didn’t have to copy someone else’s arcade game. I was allowed to design my own!”

Carlston’s phone call came in May of 1982, when Mechner was finishing up his first year at Yale University; undecided about his major as he was so much else in his life at the time, he would eventually wind up with a Bachelors in psychology. We’re granted an unusually candid and personal glimpse into his life between 1982 and 1993 thanks to his private journals, which he published (doubtless in a somewhat expurgated form) in 2012. The early years paint a picture of a bright, sensitive young man born into a certain privilege that carries with it the luxury of putting off adulthood for quite some time. He romanticizes chance encounters (“I saw a heartbreakingly beautiful young blonde out of the corner of my eye. She was wearing a blue down vest. As she passed, our eyes met. She smiled at me. As I went out I held the door for her; her fingers grazed mine. Then she was gone.”); frets frequently about cutting classes and generally not being the man he ought to be (“I think Ben is the only person who truly comprehends the depths of how little classwork I do.”); alternates between grand plans accompanied by frenzies of activity and indecision accompanied by long days of utter sloth (“Here’s what I do do: listen to music. Browse in record stores. Read newspapers, magazines, play computer games, stare out the windows. See a lot of movies.”); muses with all the self-obliviousness of youth on whether he would prefer “writing a bestselling novel or directing a blockbusting film,” as if attaining fame and fortune was as simple as deciding on one or the other.

At Yale, film, that other constant of his creative life, came to the fore. He joined every film society he stumbled upon, signed up for every film-studies course in the catalog, and set about “trying to see in four years every film ever made”; Akira Kurosawa’s classic adventure epic Seven Samurai (a major inspiration behind Star Wars among other things) emerged as his favorite of them all. He also discovered an unexpected affinity for silent cinema, which naturally led him to compare that earliest era of film with the current state of computer games, a medium that seemed in a similar state of promising creative infancy. All of this, combined with the example of Choplifter and the karate lessons he was sporadically attending, led to Karateka, the belated fruition of his obsession with getting a game published.

To a surprising degree given his youth and naivete, Mechner consciously designed Karateka as the proverbial Next Big Thing in action games after the first wave of simple quarter munchers, whose market he watched collapse over the two-plus years he spent intermittently working on it. Plenty of fighting games had appeared on the Apple II and other platforms before, some of them very playable; Mechner wasn’t sure he could really improve on their templates when it came to pure game play. What he could do, however, was give his game some of the feel and emotional resonance of cinema. Reasoning that computer games were technically on par with the first decade or two of film in terms of the storytelling tools at his disposal, he mimicked the great silent-film directors in building his story out of the broadest archetypal elements: an unnamed hero must assault a mountain fortress to rescue an abducted princess, fighting through wave after wave of enemies, culminating in a showdown with the villain himself. He energetically cross-cut the interactive fighting sequences with non-interactive scenes of the villain issuing orders to his minions while the princess looks around nervously in her cell — a suspense-building technique from cinema dating back to The Birth of a Nation. He mimicked the horizontal wipes Kurosawa used for transitions in Seven Samurai; mimicked the scrolling textual prologue from Star Wars. When the player lost or won, he printed “THE END” on the screen in lieu of “GAME OVER.” And, indeed, he made it possible, although certainly not easy, to win Karateka and carry the princess off into the sunset. The player was, in other words, playing for bigger stakes than a new high score.

The most technically innovative aspect of Karateka — suggested, like much in the game, by Mechner’s very supportive father — involved the actual people on the screen. To make his fighters move as realistically as possible, Mechner made use for the first time in a computer game of an old cartoon-animation technique known as rotoscoping. After shooting some film footage of his karate instructor in action, doing various kicks and punches, Mechner used an ancient Moviola editing machine that had somehow wound up in the basement of the family home to isolate and make prints out of every third frame. He imported the figure at the center of each print into his Apple II by tracing it on a contraption called the VersaWriter. Flipped through in sequence, the resulting sprites appeared to “move” in an unusually fluid and realistic fashion. “When I saw that sketchy little figure walk across the screen,” he wrote in his journal, “looking just like Dennis [his karate instructor], all I could say was ‘ALL RIGHT!’ It was a glorious moment.”

Doug Carlston, who clearly saw something special in this earnest kid, was gently encouraging and almost infinitely patient with him. When it looked like Mechner had come up with something potentially great at last, Carlston signed him to a contract and flew him out to California in the summer of 1984 to finish it up with the help of Brøderbund’s in-house staff. Released just a little too late to fully capitalize on the 1984 Christmas rush, Karateka started slowly but gradually turned into a hit, especially once the Commodore 64 port dropped in June of 1985. Once ported to Nintendo for the domestic Japanese market, it proceeded to sell many hundreds of thousand units, making Jordan Mechner a very flush young man indeed.

So, Mechner, about to somehow manage to graduate despite all the missed assignments and cut classes spent working on Karateka, seemed poised for a fruitful career making games. Yet he continued to vacillate between his twin obsessions. Even as his game, the most significant accomplishment of his young life and one of which anyone could justly be proud, had entered the homestretch, he had written how “I definitely want my next project to be film-related. Videogames have taken up enough of my time for now.” In the wake of his game’s release, the steady stream of royalties therefrom only made it easier to dabble in film.

Mechner spent much of the year after graduating from university back at home in Chappaqua working on his first screenplay. In between writing dialog and wracking himself with doubt over whether he really wanted to do another game at all, he occasionally turned his attention to the idea of a successor to Karateka. Already during that first summer after Yale, he and Gene Portwood, a Brøderbund executive, dreamed up a scenario for just such a beast: an Arabian Nights-inspired story involving an evil sultan, a kidnapped princess, and a young man — the player, naturally — who must rescue her. Karateka in Middle Eastern clothing though it may have been in terms of plot, that was hardly considered a drawback by Brøderbund, given the success of Mechner’s first game.

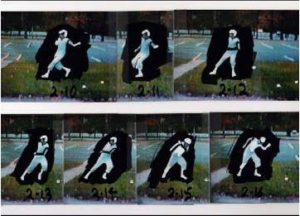

Determined to improve upon the rotoscoping of Karateka, Mechner came up with a plan to film a moving figure and use a digitizer to capture the frames into the computer, rather than tracing the figure using the VersaWriter. He spent $2500 on a high-end VCR and video camera that fall, knowing he would return them before his month’s grace period was out (“I feel so dishonest,” he wrote in his journal). The technique he had in the works may have been an improvement over what he had done for Karateka, but it was still very primitive and hugely labor-intensive. After shooting his video, he would play it back on the VCR, pausing it on each frame he wanted to capture. Then he would take a picture of the screen using an ordinary still camera and get the film developed. Next step was to trace the outline of the figure in the photograph using Magic Marker and fill him in using White-Out. Then he would Xerox the doctored photograph to get a black-and-white version with a very clear silhouette of the figure. Finally, he would digitize the photocopy to import it into his Apple II, and erase everything around the figure by hand on the computer to create a single frame of sprite animation. He would then get to go through this process a few hundred more times to get the prince’s full repertoire of movements down.

On October 20, 1985, Jordan Mechner did his first concrete work on the game that would become Prince of Persia, using his ill-gotten video camera to film his 16-year-old brother David running and jumping through a local parking lot. When he finally got around to buying a primitive black-and-white image digitizer for his trusty Apple II more than six months later, he quickly determined that the footage he’d shot was useless due to poor color separation. Nevertheless, he saw potential magic.

I still think this can work. The key is not to clean up the frames too much. The figure will be tiny and messy and look like crap… but I have faith that, when the frames are run in sequence at 15 fps, it’ll create an illusion of life that’s more amazing than anything that’s ever been seen on an Apple II screen. The little guy will be wiggling and jiggling like a Ralph Bakshi rotoscope job… but he’ll be alive. He’ll be this little shimmering beacon of life in the static Apple-graphics Persian world I’ll build for him to run around in.

For months after that burst of enthusiasm, however, he did little more with the game.

At last in September of 1986, having sent his screenplay off to Hollywood and thus with nothing more to do on that front but wait, Mechner moved out to San Rafael, California, close to Brøderbund’s offices, determined to start in earnest on Prince of Persia. He spent much time over the next few months refining his animation technique, until by Christmas everyone who saw the little running and jumping figure was “bowled over” by him. Yet after that progress again slowed to a crawl, as he struggled to motivate himself to turn his animation demos into an actual game.

And then, on May 4, 1987, came the phone call that would stop the little running prince in his tracks for the better part of a year. A real Hollywood agent called to tell him she “loved” his script for Birthstone, a Spielbergian supernatural comedy/thriller along the lines of Gremlins or The Goonies. Within days of her call, the script was optioned by Larry Turman, a major producer with films like The Graduate on his resume. For months Mechner fielded phone calls from a diverse cast of characters with a diverse cast of suggestions, did endless rewrites, and tried to play the Hollywood game, schmoozing and negotiating and trying not to appear to be the awkward, unworldly kid he still largely was. Only when Birthstone seemed permanently stuck in development hell — “Hollywood’s the only town where you can die of encouragement,” he says wryly, quoting Pauline Kael — did he give up and turn his attention back to games. Mechner notes today that just getting as far as he did with his very first script was a huge achievement and a great start in itself. After all, he was, if not quite hobnobbing with the Hollywood elite, at least getting rejection letters from such people as Michael Apted, Michael Crichton, and Henry Winkler; such people were reading his script. But he had been spoiled by the success of Karateka. If he wrote another screenplay, there was no guarantee it would get even as far as his first had. If he finished Prince of Persia, on the other hand, he knew Brøderbund would publish it.

And so, in 1988, it was back to games, back to Prince of Persia. Inspired by “puzzly” 8-bit action games like Doug Smith’s Lode Runner and Ed Hobbs’s The Castles of Dr. Creep, his second game was shaping up to be more than just a game of combat. Instead his prince would have to make his way through area after area full of tricks, traps, and perilous drops. “What I wanted to do with Prince of Persia,” Mechner says, “was a game which would have that kind of logical, head-scratching, fast-action, Lode Runner-esque puzzles in a level-based game but also have a story and a character that was trying to accomplish a recognizable human goal, like save a princess. I was trying to merge those two things.” Ideally, the game would play like the iconic first ten minutes of Raiders of the Lost Ark, in which Indiana Jones runs and leaps and dodges and sometimes outwits rather than merely outruns a series of traps. For a long while, Mechner planned to make the hero entirely defenseless, as a sort of commentary on the needless ultra-violence found in so many other games. In the end, he didn’t go that far — the allure of sword-fighting, not to mention commercial considerations, proved too strong — but Prince of Persia was nevertheless shaping up to be a far more ambitious, multi-faceted work than Karateka, boasting much more than just improved running and jumping animations.

With just 128 K of memory to work with on the Apple II, Mechner was forced to make Prince of Persia a modular design, relying on a handful of elements which are repeatedly reused and recombined. Take, for instance, the case of the loose floorboards. The first time they appear, they’re a simple trap: you have to jump over a section of the floor to avoid falling into a pit. Later, they appear on the ceiling, as part of the floor above your own; caught in an apparent cul de sac, you have to jump up and bash the ceiling to open an escape route. Still later, they can be used strategically: to kill guards below you by dropping the floorboards on their heads, or to hold down a pressure plate below you that opens a door on the level on which you’re currently standing. It’s a fine example of a constraint in game design turning into a strength. “There’s a certain elegance to taking an element the player is already familiar with,” says Mechner, “and challenging him to think about it in a different way.”

On July 14, 1989, Mechner shot the final footage for Prince of Persia: the denouement, showing the prince — now played by the game’s project manager at Brøderbund, Brian Ehler — embracing the rescued princess — played by Tina LaDeau, the 18-year-old daughter of another Brøderbund employee, in her prom dress. (“Man, she is a fox,” Mechner wrote in his journal. “Brian couldn’t stop blushing when I had her embrace him.”)

The game shipped for the Apple II on October 6, 1989. And then, despite a very positive review in Computer Gaming World — Charles Ardai called it nothing less than “the Star Wars of its field,” music to the ears of a movie buff like Mechner — it proceeded to sell barely at all: perhaps 500 units a month. It was, everyone at Brøderbund agreed, at least a year too late to hope to sell significant numbers of a game like this on the Apple II, whose only remaining commercial strength was educational software, thanks to the sheer number of the things still installed in American schools. Mechner’s procrastination and vacillation had spoiled this version’s commercial prospects entirely.

Thankfully, the Apple II version wasn’t to be the only one. Brøderbund already had programmers and artists working on ports to MS-DOS and the Amiga, the last two truly viable computer-gaming platforms in North America. Mechner as well turned his attention to the versions for these more advanced machines as soon as the Apple II version was finished. And once again his father pitched in, composing a lovely score for the luxuriously sophisticated sound hardware now at the game’s disposal. “This is going to be the definitive version of Prince of Persia,” Mechner enthused over the MS-DOS version. “With VGA [graphics] and sound card, on a fast machine, it’ll blow the Apple away. It looks like a Disney film. It’s the most beautiful game I’ve ever seen.” Reworked though they were in almost all particulars, at the heart of the new versions lay the same digitized film footage that had made the 8-bit prince run and leap so fluidly.

And yet, after it shipped on April 19, 1990, the MS-DOS version also disappointed. Mechner chafed over his publisher’s disinterest in promoting the game; they seemed on the verge of writing it off, noting how the vastly superior MS-DOS version was being regarded as just another port of an old 8-bit game, and thus would likely never be given a fair shake by press or public. True as ever to the bifurcated pattern of his life, he decided to turn back to film. Having tried and failed to get into New York University film school, he resorted to working as a production assistant in movies by way of supporting himself and trying to drum up contacts in the film-making community of New York. Thus the first anniversary of Prince of Persia‘s original release on the Apple II found him schlepping crates around New York City. His career as a game developer seemed to be behind him, and truth be told his prospects as a filmmaker didn’t look a whole lot brighter.

The situation began to reverse itself only after the Amiga version was finished — programmed, as it happened, by Dan Gorlin, the very fellow whose Choplifter had first inspired Mechner to look at his own games differently. In Europe, the Amiga’s stronghold, Prince of Persia was free of the baggage which it carried in North America — few in Europe had much idea of what an Apple II even was — and doubtless benefited from a much deeper and richer tradition on European computers of action-adventures and platform puzzlers. It received ebullient reviews and turned into a big hit on European Amigas, and its reputation gradually leaked back across the pond to turn it at last into a hit in its homeland as well. Thus did Prince of Persia become a slow grower of an international sensation — a very unusual phenomenon in the hits-driven world of videogames, where shelf lives are usually short and retailer patience shorter. Soon came the console releases, along with releases for various other European and Japanese domestic computers, sending total sales soaring to over 2 million units.

By the beginning of 1992, Mechner was far removed from his plight of just eighteen months before. He was drowning in royalties, consulting intermittently with Brøderbund on a Prince of Persia 2 — it was understood that his days in the programming trenches were behind him — and living a globetrotting lifestyle, jaunting from Paris to San Rafael to Madrid to New York as whim and business took him. He was also planning his first film, a short documentary to be shot in Cuba, and already beginning to mull over what would turn into his most ambitious and fascinating game production of all, known at this point only as “the train game.”

Prince of Persia, which despite the merits of that eventual “train game” is and will likely always remain Mechner’s signature work, strikes me most of all as a triumph of presentation. The actual game play is punishingly difficult. Each of its twelve levels is essentially an elaborate puzzle that can only be worked out by dying many times when not getting trapped into one of way too many dead ends. Even once you think you have it all worked out, you still need to execute every step with perfect precision, no mean feat in itself. Messing up at any point in the process means starting that level over again from the beginning. And, because you only have one hour of real time to rescue the princess, every failure is extremely costly; a perfect playthrough, accomplished with absolute surety and no hesitations, takes about half an hour, leaving precious little margin for error. At least there is a “save” feature that will let you bookmark each level starting with the third, so you don’t have to replay the whole game every time you screw up — which, believe me, you will, hundreds if not thousands of times before you finally rescue the princess. Beating Prince of Persia fair and square is a project for a summer vacation of those long-gone adolescent days when responsibilities were few and distractions fewer. As a busy adult, I find it too repetitive and too reliant on rote patterns, as well as — let’s be honest here — just too demanding on my aging reflexes. In short, the effort-to-reward ratio strikes me as way out of whack. Of course, I’m sure that, given Prince of Persia‘s status as a beloved icon of gaming, many of you have a different opinion.

So, let’s turn back to something on which we can hopefully all agree: the brilliance of that aforementioned presentation, which brings to aesthetic maturity many of the techniques Mechner had first begun to experiment with in Karateka. Rather than using filmed footage as a tool for the achievement of fluid, lifelike motion, as Mechner did, games during the years immediately following Prince of Persia would be plastered with jarring chunks of poorly acted, poorly staged “full-motion video.” Such spectacles look far more dated today than the restrained minimalism of Prince of Persia. The industry as a whole would take years to wind up back at the place where Jordan Mechner had started: appropriating some of the language of cinema in the service of telling a story and building drama, without trying to turn games into literal interactive movies. Mechner:

Just as theater is its own thing — with its own conventions, things that it does well, things it does badly — so is film, and so [are] computer games. And there is a way to borrow from one medium to another, and in fact that’s what an all-new medium does when it’s first starting out. Film, when it was new, looked like someone set up a camera front and center and filmed a staged play. Then the things that are specific to film — like the moving camera, close-ups, reaction shots, dissolves — all these kinds of things became part of the language of cinema. It’s the same with computer games. To take a long film sequence and to play that on your TV screen is the bad way to make a game cinematic. The computer game is not a VCR. But if you can borrow from the knowledge that we all carry inside our heads of how cuts work, how reaction shots work, what a low angle means dramatically, what it means when the camera suddenly pulls back… We’ve got this whole collective unconscious of the vocabulary of film, and that’s a tremendously valuable tool to bring into computer gaming.

In a medium that has always struggled to tamp down its instinct toward aesthetic maximalism, Mechner’s games still stand out for their concern with balance and proportion. Mechner again:

Visuals are [a] component where it’s often tempting to compromise. You think, “Well, we could put a menu bar across here, we could put a number in the upper right-hand corner of the screen representing how many potions you’ve drunk,” or something. The easy solution is always to do something that as a side effect is going to make the game look ugly. So I took as one of the ground rules going in that the overall screen layout had to be pleasing, had to be strong and simple. So that somebody who was not playing the game but who walked into the room and saw someone else playing it would be struck by a pleasing composition and could stop to watch for a minute, thinking, “This looks good, this looks as if I’m watching a movie.” It really forces you as a designer to struggle to find the best solution for things like inventory. You can’t take the first solution that suggests itself, you have to try to solve it within the constraints you set yourself.

Mechner’s take on visual aesthetics can be seen as a subversion of Ken Williams’s old “ten-foot rule,” which, as you might remember, stated that every Sierra game ought to be visually arresting enough to make someone say “Wow!” when glimpsing it from ten feet away across a crowded shop. Mechner believed that game visuals ought to be more than just striking; they ought to be aesthetically good by the more refined standards of film and the other, even older visual arts. All that time Mechner spent obsessing over films and film-making, which could all too easily be labeled a complete waste of time, actually allowed him to bring something unique to the table, something that made him different from virtually all of his many contemporaries in the interactive-movie business.

There are various ways to situate Jordan Mechner’s work in general and Prince of Persia in particular within the context of gaming history. It can be read as the last great swan song of the Apple II and, indeed, of the entire era of 8-bit computer gaming, at least in North America. It can be read as yet one more example of Brøderbund’s downright bizarre commercial Midas touch, which continued to yield a staggering number of hits from a decidedly modest roster of new releases (Brøderbund also released SimCity in 1989, thus spawning two of the most iconic franchises in gaming history within bare months of one another). It can be read as the precursor to countless cinematic action-adventures and platformers to come, many of whose designers would acknowledge it as a direct influence. In its elegant simplicity, it can even be read as a fascinating outlier from the high-concept complexity that would come to dominate American computer gaming in the very early 1990s. But the reading that makes me happiest is to simply say that Prince of Persia showed how less can be more.

(Sources: Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; The Making of Karateka and The Making of Prince of Persia by Jordan Mechner; Creative Computing of March 1979, September 1979, and May 1980; Next Generation of May 1998; Computer Gaming World of December 1989; Jordan Mechner’s Prince of Persia postmortem from the 2011 Game Developers Conference; “Jordan Mechner: The Man Who Would Be Prince” from Games™; the Jordan Mechner and Brøderbund archives at the Strong Museum of Play.)