Joel Billings of SSI never had a whole lot of use for Dungeons & Dragons, TSR, or RPGs in general. In this he was hardly unique among hardcore wargamers. The newer hobby had arisen directly from the older, forcing each and every grognard to a judgement and a reckoning. Some wargamers saw in RPGs the experiential games they had really been wanting to play all along; they jumped onto the RPG bandwagon and never looked back. Others, the ones who found Montgomery and Rommel far more interesting than Frodo and Sauron, scoffed at RPGs and their silly fantasies and clung all the tighter to their Avalon Hill and SPI boxes. And of course some split the difference, playing a little of this and a little of that.

Joel counted himself among the scoffers. His one experience with playing Dungeons & Dragons hadn’t been a positive one: a sadistic Dungeon Master killed his whole party before he had even begun to figure out what was going on. “This is the stupidest game I’ve ever seen,” he concluded. He never felt seriously tempted to try it again.

By the time that SSI was off and running, Joel and other wargame stalwarts like him had more reasons than ever to dislike RPGs. The late 1970s, you’ll remember, had seen the wargame at its commercial zenith, the RPG the exciting, fast-rising upstart genre. As the 1980s dawned and Dungeons & Dragons exploded into a popularity no wargame had ever dreamed of, it was hard not to blame one genre’s rapid rise for the other’s slow decline. Already in 1982 SPI, alongside Avalon Hill one of the twin giants of wargaming, found themselves in a serious financial crisis brought on partly by the general decline of the wargame market, partly by the general recession afflicting the American economy at the time, and partly by general mismanagement all too typical of their hobbyist-driven industry. TSR, now more than ten times the size of SPI thanks to the Dungeons & Dragons fad, gave them a secured loan of $425,000 to keep their doors open a while longer.

It will likely never be known whether what happened next was the result of Machiavellian scheming or just Gary Gygax and the Blume brothers’ usual bumbling approach to running TSR. Just two weeks after giving SPI the loan, TSR inexplicably called it in again. Having already used TSR’s money to satisfy their other creditors, SPI had no possible way to pay back the loan. TSR therefore foreclosed, announcing that they were taking over SPI. Shortly thereafter, realizing that SPI was so financially upside down as to become a negative asset on their books, they announced that what they had actually meant to say was that they were assuming ownership of all of SPI’s assets but none of their debts. When SPI’s creditors balked at this brazen attempt by TSR to have their cake and eat it too, TSR negotiated to pay them off for pennies on the dollar; something was better than nothing, figured the creditors. The end result was an SPI bankruptcy filing in effect if not in fact.

But any old wargamer who thought that the TSR purchase heralded better days for the company and the hobby was quickly disabused of that notion. TSR proved a terrible steward of SPI’s legacy, alienating their entire old design team so badly that they left en masse to reform as a new Avalon Hill subsidiary called Victory Games. Worse, TSR claimed that their acquisition of SPI’s assets had not included the paid-up subscriptions to SPI’s beloved house organ Strategy & Tactics; subscriptions were not assets at all, you see, but “liabilities.” Every Strategy & Tactics subscriber, even those who had splashed out a bundle for a “lifetime” subscription, would have to re-up immediately to continue receiving the magazine. And no, there would be no compensation for missed issues from the old regime. This act of betrayal of SPI’s most loyal customers didn’t just kill the most respected wargaming magazine in the world; it also, as Greg Costikyan puts it, shot the old subculture of wargaming in general in the head.

So, if a veteran wargamer like Joel Billings needed further reason to dislike all this Dungeons & Dragons silliness, there he had it. Trip Hawkins, a member of SSI’s board from the company’s inception, claims that he started telling Joel that he should branch out into CRPGs almost immediately after SSI was founded. But, although SSI quickly began to supplement their wargames with sports titles and other sorts of strategy games, Joel resisted CRPGs, saying that he preferred to publish “the games that he enjoyed personally.” RPGs, whether played on the tabletop or the desktop, clearly weren’t in that category.

Although Joel did nothing to encourage CRPG submissions, in late 1983 a fairly decent one arrived of its own accord. Written by two teenage brothers, Charles and John Dougherty, Questron had already ping-ponged around the industry a bit before it reached SSI. When the Dougherty brothers had sent it to Origin Systems, Richard Garriott had not only rejected it but told them in no uncertain terms to expect legal trouble if they dared to release something he considered to be so obviously derivative of his own Ultima games. Word of Garriott’s displeasure may very well have made the other major publishers shy away, until it ended up with the Doughertys’ long-shot, nichey little SSI. Joel decided that, with a first entry in the genre all but gift-wrapped on his desk, he might as well dip a toe into these new waters and see how it went. SSI published Questron in February of 1984, albeit only after finding a way to placate an angry Garriott, who learned of their plans to do so at the January 1984 Winter Consumer Electronics Show and pitched a royal fit. Joel gave him a small stake in Questron‘s action and a small note on its box: “Game structure and style used under license of Richard Garriott.”

Questron proved a modest start to something very significant. The game, benefiting from the lack of new Ultima or Wizardry titles during 1984, did unexpectedly well. In fact, when the Commodore 64 port of the Apple II original shipped in August, it became the fastest-selling new release SSI had ever enjoyed. The final total would hit almost 35,000 copies, pretty good numbers for a company whose average game still failed to break 10,000 copies. Some meeting notes dated December 2, 1984, make the new thinking that resulted clear: “Going into fantasy games now, could really affect sales favorably.” A little over a month later, SSI was already going through something of an identity crisis: are we a “wargame company” or a more generalized “computer-game company,” more meeting notes plaintively ask.

But SSI would have a hard time building on the momentum of Questron in the time-honored game-industry way of turning it into a franchise. In the contract the Dougherty brothers had signed with SSI, the latter was granted a right of first refusal of a potential sequel. This put the Doughertys in essentially the same situation as a restricted free agent in sports: they were free to shop a potential Questron II to other publishers if they wished, but they had to allow SSI the chance to match any publisher’s offer before signing a final contract. Not understanding or choosing to ignore this stipulation, the Doughertys allowed themselves to be poached by none other than Trip Hawkins’s Electronic Arts, who, with The Bard’s Tale series still in the offing, were eager to hedge their bets with another potential new CRPG franchise. SSI knew nothing about what was going on until the Doughertys announced that they had gone over to the slicker, better-distributed Electronic Arts — farewell and thank you very much for everything. Feeling compelled to defend his own company’s interests, Joel sued Electronic Arts and the Doughertys. A potential Questron series remained in limbo, its momentum dissipating, while the lawsuit dragged on. The situation doubtless made for some strained times back at SSI’s offices, where board-member Trip Hawkins was still coming every month for the directors meeting.

The suit wasn’t settled until April of 1987, ostensibly at least largely in SSI’s favor. The Doughertys’ long-delayed sequel was published shortly thereafter by Electronic Arts, but under the new title of Legacy of the Ancients. Meanwhile the Doughertys were obliged to design, but not to program, a Questron II for SSI; the programming of the sequel could either be done in-house by SSI or outsourced elsewhere at their discretion. It ended up going to Westwood Associates, a frequent SSI contractor on ports and other unglamorous technical tasks who would soon be making a bigger name for themselves as a developer of original games. Released at last in February of 1988, Questron II felt rather uninspired, as one might expect given the forced circumstances of its creation. It did surprisingly well, though, outselling the first Questron by some 16,000 copies. Rather than its own merits, its success was likely down to increasing enthusiasm for CRPGs in general among gamers, and to other things going on that year that were suddenly making little SSI among the biggest names in the genre.

In the immediate wake of Questron I‘s release and success, however, those events were still well in the future. Neither Joel Billings’s troubles with his two teenage problem children nor his personal ambivalence toward CRPGs deterred him from recognizing the potential that game had highlighted. Never a publisher to shy away from releasing lots of games, SSI added CRPGs to their ongoing firehose of new wargames. To Joel Billings the businessman’s pleasure if perhaps to Joel Billings the wargamer’s chagrin, the average SSI CRPG continued to do far, far better than the average wargame. Indeed, their very next CRPG(ish) game after Questron, an unusual action hybrid called Gemstone Warrior released in December of 1984, became their first game of any type to top 50,000 copies sold. The more traditional Phantasie — names weren’t really SSI’s strong suit — in March of 1985 also topped the magic 50,000 mark. Soon the CRPGs were coming almost as quickly as the wargames: Rings of Zilfin (January 1986, 17,479 sold); Phantasie II (February 1986, 30,100 sold); Wizard’s Crown (February 1986, 47,676 sold); Shard of Spring (July 1986, 11,942 sold); Roadwar 2000 (August 1986, 44,044 sold); Gemstone Healer (September 1986, 6030 sold); Realms of Darkness (February 1987, 9022 sold); Phantasie III (March 1987, 46,113 sold); The Eternal Dagger (June 1987, 18,471 sold); Roadwar Europa (July 1987, 18,765 sold).

As the list above attests, sales figures for these games were all over the place, but trended generally a bit downward over time as SSI flooded the market. Yet one thing did remain constant: the average SSI CRPG continued to outsell the average SSI wargame by a healthy margin. (The only exception to this rule was Roger Damon’s remarkable Wargame Construction Set, which after its release in October of 1986 became a surprise hit, the first SSI game to crack 60,000 copies sold.) All of these SSI CRPGs — so many coming so close together that it’s difficult even for dedicated fans of the genre’s history to keep them all straight — occupied a comfortable if less than prestigious second rung in the industry as a whole. To describe them as the games you played while you waited for the next Ultima or The Bard’s Tale may sound unkind, but it’s largely accurate. Like SSI’s other games, they tended to be a little bit uglier and a little bit clunkier than the competition.

At their best, though, the rules behind these games felt more consciously designed than the games in the bigger, more respected series — doubtless a legacy of SSI’s wargame roots. This quality is most notable in Wizard’s Crown. The most wargamey of all SSI’s CRPGs, Wizard’s Crown was not coincidentally also the first CRPG to be designed in-house by the company’s own small staff of developers, led by Paul Murray and Keith Brors, the two most devoted tabletop Dungeons & Dragons fans in the office. Built around a combat engine of enormous tactical depth in comparison to Ultima and The Bard’s Tale, it may not be a sustainedly fun game — the sheer quantity and detail of the fights gets exhausting well before the end, and the game has little else to offer — but it’s one of real importance in the history of both SSI and the CRPG. Wizard’s Crown and its sequel The Eternal Dagger, you see, were essentially a dry run for the series of games that would remake SSI’s image.

Coming off a disappointing 1986, the first year in which SSI had failed to increase their earnings over the previous year, Joel Billings was greeted with some news that was rapidly sweeping the industry: that TSR was interested in making a Dungeons & Dragons computer game, and that they would soon be listening to pitches from interested parties. To say that Dungeons & Dragons was a desirable license hardly begins to state the case. This was the license in CRPGs, the name that inexplicably wasn’t there already, a yawning absence about to become a smothering presence at last. Everyone wanted it, and had wanted it for quite some time. That group included SSI as much as anyone; once again pushing aside any misgivings about getting into bed with the company that had shot his own favorite hobby in the head, Joel had been one of the many to contact TSR in earlier years, asking if they were interested in a licensing deal. They hadn’t been then, but now they suddenly were. Encouraged by Murray and Brors and other rabid Dungeons & Dragons fans around the office, Joel decided to put on a “full-court press,” as he describes it, to spare no effort in trying to get the deal for his own little company. Sure, it looked like one David versus a whole lot of Goliaths, but what the hell, right?

The full list of Goliaths with which SSI was competing for the license has never been published, but in interviews Joel has mentioned Origin Systems (of Ultima fame) and Electronic Arts (of The Bard’s Tale fame) as having been among them. As for the other contenders, we do know that there were at least seven more of them. One need only understand the desirability of the license to assume that the seven (or more) must have been a veritable computer-game who’s who. “We were going head to head with the best in the industry,” remembers Chuck Kroegel, a programmer and project manager on SSI’s in-house development team.

SSI was duly granted their hearing, scheduled for April 8, 1987, at TSR’s Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, headquarters. With a scant handful of weeks to prepare, they scrambled desperately to throw together some technology demos; these felt unusually important to SSI’s pitch, given that they were hardly known as a producer of slick or graphically impressive games. Those with a modicum of artistic talent digitized some monster portraits out of the Monster Manual on a Commodore Amiga, coloring them and adding some spot animation. Meanwhile the programmers put together a scrolling three-dimensional dungeon maze, reminiscent of The Bard’s Tale but better (at least by SSI’s own reckoning), on a Commodore 64.

But it was always understood that these hasty demos were only a prerequisite for making a pitch, a way to show that SSI had the minimal competency to do this stuff rather than a real selling point. When SSI’s five-man team — consisting of Joel Billings, Keith Brors, Chuck Kroegel, the newly hired head of internal development Victor Penman, and Vice President of Sales Randy Broweleit — boarded their plane for Lake Geneva, they were determined to really sell TSR on a vision: a vision of not just a game or two but a whole new computerized wing of Dungeons & Dragons that might someday equal or eclipse the tabletop variant. The pitch document that accompanied their presentation has been preserved in the SSI archive at the Strong Museum of Play. I want to quote its key paragraphs, the “Overview,” in full.

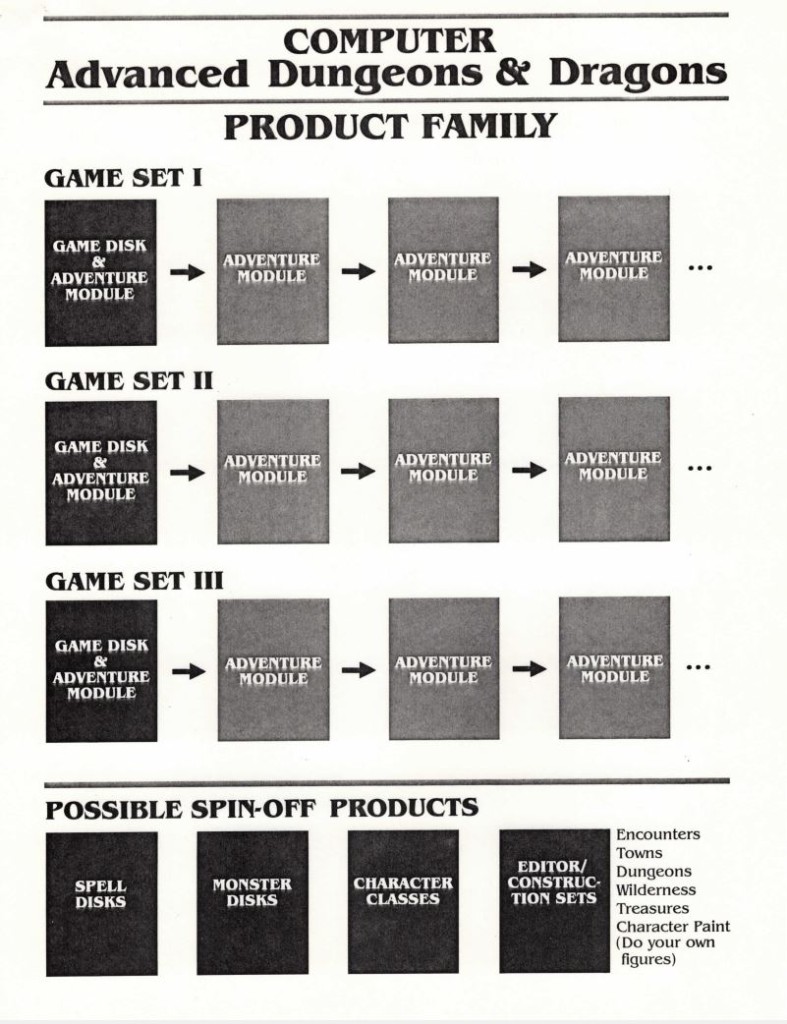

The Advanced Dungeons & Dragons computer game system would be provided as a series of modules built around a central character-creation, combat, and magic system. The first release would be this central system, which would include a modest dungeon adventure. It would be followed by the release of a number of adventure modules suitable for beginning-level characters. With the passage of time, higher-level adventures and more character types would be offered. Editors which would permit users to create their own dungeons, outdoors, and cities would also be provided. The timing on the introduction of these later releases would be determined by market demand.

The first release would be the central system. It would be similar to the Player’s Handbook in that it would provide for the creation of a number of character classes, combat, and spells. The players would draw on these abilities to create their characters for adventuring. Also included in this first release would be an introductory dungeon adventure in which the computer program would perform as DM.

This first release would be followed by a number of adventure games similar to TSR’s dungeon and adventure modules. The earliest of these would be aimed at beginning characters. As time passed and players had an opportunity to build up more powerful characters, more challenging modules would be released.

It is anticipated that at least three game sets will be released as a result of periodic improvements in and expansions of the game system. Each of these would be built on an improved and expanded version of the central system. The systems would be kept upwardly compatible so that characters developed on earlier versions of the system could take advantage of its improvements. Dungeon and adventure modules would be created for each of these game sets.

At some point (to be determined by marketing considerations) a number of editors would be released. These editors would enable the users to create their own computer adventures. The first of these would be a Dungeon Master’s Guide-type package, which would provide instructions and tools for setting up the adventures and a Monster Manual-type package to provide monsters for these adventures (the monster disk might be released much earlier since we can see non-DMs wanting it). Specialized packages for creating outdoor adventures, city adventures, overland adventures, seafaring adventures, underwater adventures, etc., would be added to meet market demand.

SSI’s original plan for a Dungeons & Dragons “product family,” as presented at their pitch. You can see glimmers of what would come later here — the eventual “Gold Box” line of CRPGs would be grouped into three separate series, each offering the chance to import characters from one game into the next — but the idea of a central “game disk” and add-on “adventure modules” would be thankfully abandoned.

In some ways, what this overview offers is a terrible vision. The Wizardry series had opted for a similar overly literal translation of Dungeons & Dragons‘s core-game/adventure-module structure, requiring anyone who wanted to play any of the later games in the series to first buy and play the first in order to have characters to import. The fallout from that decision was all too easy to spot in the merest glance at the CRPG market as of 1987: the Wizardry series had long since pissed away the position of dominance it had enjoyed after its first game to become an also-ran (much like SSI’s own CRPG efforts) to Ultima and The Bard’s Tale.

On the other hand, though, this overview is a vision, which apparently stood it in marked contrast to most other pitches, focused as they were on just getting a single Dungeons & Dragons game out there as quickly as possible so everyone could start to clean up. TSR innately understood SSI’s more holistic approach. With the early 1980s Dungeons & Dragons fad now long past, their business model relied less on selling huge quantities of any one release than in leveraging — some would say “exploiting” — their remaining base of hardcore players, each of whom was willing to spend lots of money on lots of new products.

Further, the TSR people and the SSI people immediately liked and understood one another; the importance of being on the same psychological wavelength as a potential business partner should never be underestimated. Born out of wargames, TSR seemed to have that culture and its values entwined in their very DNA, even after the ugly SPI episode and all the rest of the chaos of the past decade and change. Many of the people there knew exactly where scruffy little SSI was coming from, born and still grounded in the culture of the tabletop as they were. These same folks at TSR weren’t so sure about all those bigger, slicker firms. While Joel Billings may not have had a lot of personal use for Dungeons & Dragons, that certainly wasn’t true of many of his employees. Joel claims that the “bottom line” that sold TSR on SSI was “an R&D staff that knows AD&D games, plays AD&D games, and enjoys AD&D games.” They would feel “honored to be doing computer AD&D games. If you’re doing fantasy games, the AD&D game is the one to do.” Chuck Kroegel sums up SSI’s biggest advantage over their competitors in fewer words: “We wanted this project more than the other companies.” That genuine personal interest and passion, along with SSI’s idea that this would be a big, ambitious, multi-layered, perhaps era-defining collaboration — TSR had never been known for thinking small — were the important things. The details could be worked out later.

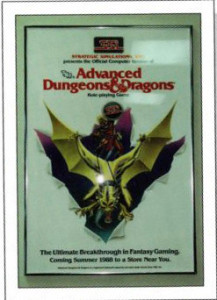

At the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June — yes, it’s that landmark CES again — SSI and TSR announced their unlikely partnership, formally signing the contract right there at the show in front of the press and SSI’s shocked rivals. The contract was for five years of Dungeons & Dragons software, with options to renew thereafter. It would officially go into effect on January 1, 1988, although development of a planned torrent of products would start immediately.

There would be three distinct Advanced Dungeons & Dragons product lines. One line, which grew out of whole cloth during the negotiations, would be a series of “multi-player action/arcade games” that used settings and characters from TSR’s various novels and supplements, but otherwise had little to do with the tabletop game: “These games will focus on special aspects of AD&D, such as swordplay, spell-casting, and dungeon and wilderness exploration.” Having no particular competence in the area of action games, SSI would sub-contract with their European publishers, U.S. Gold, to make these games, drawing from the deep well of hotshot British game programmers to which U.S. Gold had access.

Another line evolved out of SSI’s original plan for a sort of “Dungeons & Dragons Construction Set.” Instead of letting Dungeon Masters make new computerized adventures — SSI and TSR, like many other companies, were worried about killing the market for future games by putting too good game-making tools in the hands of players — the Dungeon Masters Assistant line would be designed to aid in the construction of adventures and campaigns for the tabletop game.

And finally there was the big line: a full-fledged implementation of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons as a series of CRPGs. The idea of a “central system” with “adventure modules” blessedly disappeared within a few months of the contract signing, replaced by a series of standalone games that would allow those who wished to do so to import the same party into each sequel; those who didn’t wish to do so, or who hadn’t played the earlier games at all, would still be able to create new characters in the later games.

The choice of a partner for this high-profile deal had been driven entirely by the creative types at TSR and the kinship they felt for SSI. That’s doubly surprising when you consider that it occurred well into the reign of Lorraine Williams, whose supposed dislike of games and gamers and constant meddling in the design process would later win her an infamous place in fan legend as the most loathed real-life villain in the history of the tabletop RPG. Whatever the veracity of the other claims made against her, in this case she ignored lots of very sensible questions to let her creative people have the partner they wanted. Could nichey little SSI improve their marketing and distribution enough to get the games in front of as many potential customers as someone like Electronic Arts? Could SSI raise the standards of their graphics and programming to make something attractive and slick enough to match the appeal of the Dungeons & Dragons trademark? In short, was SSI really up to this huge project, many times greater in scope than anything they’d done before? Lorraine Williams was betting five years of her flagship brand’s future, the most precious thing TSR owned, on the answer to all of these questions being yes. It was one hell of a roll of the dice.

If SSI was to pull it off, they would have to mortgage their hopefully bright future as the software face of Dungeons & Dragons and expand dramatically. In the months following the contract-signing ceremony, their in-house development staff expanded from 7 to 25 people. Among the new hires were SSI’s first full-time pixel artists, hired to give the new products a look worthy of the license. SSI’s games having never been the sort to wow anyone with their beauty, figuring out the graphics thing presented perhaps the greatest challenge of all, as Victor Penman recognized:

In the past, when SSI was primarily a wargames company, graphics were not as important as game play. Now the graphics will be better, making this product more of an improvement than any other. We’re committed to carrying out state-of-the-art graphics all the way down the line, so we’re dedicated to game sophistication and a new level of graphics more so than anything we’ve done to date.

With the action games outsourced to U.S. Gold and the Dungeon Masters Assistant line being less demanding projects likely to be of only niche appeal anyway, the big push at SSI was on the first full-fledged Dungeons & Dragons CRPG. The new project used the two Wizard’s Crown games, especially those games’ intricate tactical-combat system, as a jumping-off point; most of the SSI veterans who had worked on those games were now employed on this new one. But that could only be a jumping-off point, for SSI’s plans needed to be much more ambitious now to please both TSR and the gaming public, who would expect this first real Dungeons & Dragons CRPG to be something really, truly special. As the first CRPG of a series that would come to include many more, a whole software ecosystem needed to be built from scratch to create it. A multi-platform game engine, interpreters, scripting languages, and level editors were all needed just for starters.

In a move that SSI would soon have cause to regret, the tool chain was built around the Commodore 64, then enjoying its belated final year as the American home-computer industry’s dominant platform. The choice isn’t hard to understand in the context of 1987: the 64 had been around for so long and for so strong that one could almost believe it would continue forever. SSI had sold 35 percent of all their games on the Commodore 64 during 1986, 10 percent more than its closest rival, the Apple II. If anything, these numbers were low for the industry in general, reflecting SSI’s specialization in cerebral strategy games, traditionally a bastion of the Apple II market. With this new partnership, SSI’s bid for the big time, there seemed every reason to think that the 64’s percentage of the pie would only increase. Therefore they would build and release the Dungeons & Dragons games first on the Commodore 64, ensuring that they looked and ran well on that all-important platform. Then they could adapt the same engine to run on the other, often more capable platforms.

The arrival of Dungeons & Dragons at SSI and the dramatic upending of the daily routine that it wrought created inevitable tensions at what had always been a low-key, workmanlike operation. The minority of staffers assigned to the non-Dungeons & Dragons business-as-usual — i.e., the company’s wargames and the last sprinkling of non-licensed CRPGs in the pipeline — started to feel, in the words of Chuck Kroegel, like “outcasts.” Staffers referred to themselves as either working in Disneyland (everything Dungeons & Dragons) or being exiled to Siberia (everything non-Dungeons & Dragons). Sometimes those descriptions could feel distressingly literal: desperate for space, SSI exiled the small team that tested and perfected non-Dungeons & Dragons external submissions to an unheated, cheerless nearby building. “There was a feeling on their part that we were getting all the goodies and they got all the cold Arctic air,” remembers Keith Brors.

Jim Ward, who got on fabulously with SSI, visits along with his plus-one in 1990 to celebrate the company’s tenth anniversary.

The folks in Disneyland got plenty of help from Lake Geneva. In the beginning the TSR/SSI partnership really was a partnership, standing it in marked contrast to most similar licensing deals. The scenario for the first Dungeons & Dragons CRPG was first written and designed as a tabletop adventure module by three of TSR’s most experienced staff designers, working under one Jim Ward, whose own history with Dungeons & Dragons went back to well before that name existed, when he had played in Gary Gygax’s earliest campaigns. The tabletop module was passed on to SSI for implementation on the computer in January of 1988. SSI had their hands plenty full before that date just getting the game engine up and running; that job was described by Victor Penman as “equivalent to producing the Player’s Handbook, the Dungeon Master’s Guide, and the Monster Manual in one program.”

TSR’s close involvement ensured that the end result really did feel like tabletop Dungeons & Dragons, more so than any of the competing CRPG series — and this, of course, was exactly what its audience wanted. Ward’s team chose to set the game in TSR’s new campaign world of the Forgotten Realms, envisioned as the more generic, default alternative to the popular but quirky Dragonlance world of Krynn. The big boxed set that introduced the Forgotten Realms was published well after the contract signing with SSI, allowing TSR to carve out a space on the world’s map reserved for the computer games right from the outset. While many have grumbled that words like “generic” and “default” do all too good a job of describing the Forgotten Realms — “vanilla” is another strong candidate — Ward and company nevertheless drowned their scenario in the lore of the place, such as it is, leading to a CRPG with a sense of place comparable only to the Ultima series and its world of Britannia. To further cement the connection between Dungeons & Dragons the tabletop game and its computerized implementation, TSR prepared tie-in products of their own, including a novelization of the first CRPG written by Jim Ward with the help of Jane Cooper Hong and the original tabletop adventure module that had served as SSI’s design document.

SSI had promised TSR when making their original pitch that they could have an official Dungeons & Dragons CRPG ready to go within thirteen months at the outside of signing a deal. Joel Billings always took great pride in his company’s punctuality. Lingering, “troubled” projects of any stripe were a virtual unknown there during the 1980s; outside and in-house developers alike quickly learned to just get their games done and move on to the next if they wanted to continue to work with SSI. Dungeons & Dragons proved to be no exception. SSI would manage to meet their deadline of summer 1988.

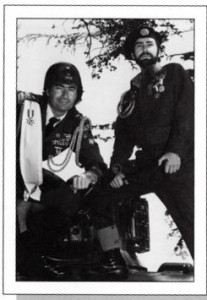

With the big day drawing near, Joel Billings took an important step to address the still-lingering questions about whether SSI had the promotional and distributional resources to properly sell Dungeons & Dragons on the computer. It marked the next phase in SSI’s long, multi-faceted relationship with Trip Hawkins and his company Electronic Arts. Barely a year removed from settling SSI’s lawsuit and less than a year removed from losing the big TSR contract to them, Electronic Arts bought into SSI to the tune of 20 percent in May of 1988, giving the smaller company some much-needed cash to spend on a big Dungeons & Dragons promotional effort. SSI also became one of Electronic Arts’s affiliated labels, thus solving the distribution problems. As previous tales told on this blog will attest, such deals with the titans of the industry could be dangerous territory for smaller publishers like SSI. But SSI did have advantages that most of the affiliated labels didn’t: in addition to the longstanding personal relationship enjoyed by Trip Hawkins and Joel Billings, the buy-in would give Electronic Arts a real stake in SSI’s success, making them much harder to gut and cast aside if they should disappoint.

Grognards to the end, Trip Hawkins and Joel Billings dress up as generals to celebrate their “strategic alliance” of May 1988.

SSI released the first title in all three branches of their new Dungeons & Dragons family tree in August of 1988, each on a different platform of the several each title would eventually reach. Dungeon Masters Assistant Volume I: Encounters shipped on the Apple II. It would sell 26,212 copies across four platforms — not bad for such a specialized utility. Heroes of the Lance, an action game set in Dragonlance‘s world of Krynn that was developed and delivered as promised from Britain, shipped on the Atari ST. The first of what would come to be known as the “Silver Box” line of action-oriented Dungeons & Dragons games, it would sell an impressive 88,808 copies across four platforms, enough to easily qualify it as SSI’s all-time biggest seller.

Enough, that is, if it hadn’t been for Pool of Radiance, first of the “Gold Box” line of full-on Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs. Recognized as The Big One in the lineup right from the start, it didn’t disappoint. Beginning on the Commodore 64 and moving on to MS-DOS, the Apple II, the Macintosh, and the Amiga, its final sales total reached 264,536 copies in North America alone. By far the most successful release of SSI’s history as an independent company, it became exactly the transformative work that SSI (and Electronic Arts) had been banking on, a ticket to the big leagues if ever there was one. Even the Pool of Radiance clue book outsold any previous SSI game, to the tune of 68,395 copies.

The second serious attempt of 1988 to adapt a set of tabletop-RPG rules to the computer, Pool of Radiance makes, like its contemporary Wasteland, an enlightening study in game design for that reason and others. Happily, it’s mostly worthy of its huge success; there’s a really compelling game in here, even if you sometimes have to fight a little more than you ought to to tease it out. As a game, it’s more than worthy of an article in its own right. By way of concluding my little series on SSI and TSR and my bigger one on the landmark CRPGs of 1988, I’ll give it that article next time.

(Sources: As with all of my SSI articles, much of this one is drawn from the SSI archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Other sources include the Questbusters of March 1988, Computer Gaming World of March 1988 and July 1988, and Dragon of November 1987, May 1988, and July 1990. Also the book Designers and Dragons by Shannon Appelcline, and Matt Barton’s video interviews with Joel Billings.)