For a company that’s long since gone down into history as the foremost proponent of the all-text adventure game, Infocom sure spent a lot of years fretting over graphics. As early as 1982, well before starting their iconic text-only advertising campaign, they entered into discussions with Mark Pelczarski of Penguin Software about a possible partnership that would have seen Antonio Antiochia, writer and illustrator of Penguin’s hit adventure Transylvania, drawing pictures for Infocom games using Penguin’s The Graphics Magician. When that combination of Penguin’s graphics technology with Infocom’s text-only Z-Machine was judged impractical, the all-text advertising campaign went forward, but still Infocom refused to rule out graphics internally. On the contrary, they used some of the revenue from 1983, their first really big year, to start a graphics research group of their own under the stewardship of Mike Berlyn. But that attempt at a cross-platform graphics system, a sort of Z-Machine for graphical games, petered out almost as quietly as the Penguin deal, resulting only in Berlyn’s unique but ultimately underwhelming computerized board game Fooblitzky. Specifying a single set of graphics capabilities achievable by all of the diverse computers on the market meant that those graphics had to be very primitive, and, thanks to the fact that they were running through an interpreter, slow to boot. In the end Fooblitzky made it only to the Apple II, the Atari 8-bits, and the PC clones, and even that was a struggle. Certainly trying to combine this already problematic system with the sort of adventure game that was Infocom’s bread and butter seemed hopeless. Thus the graphics group was quietly dispersed amid all the other downsizing of 1985. Strike two.

After completing Trinity in 1986, Brian Moriarty decided to see if he could make the third time the charm. The fundamental problem which had dogged Infocom’s efforts to date had been the big DEC PDP-10 that remained at the heart of their development system — the same big mainframe that, once lauded as the key to Infocom’s success, was now beginning to seem more and more like a millstone around their necks. Bitmap graphics on the DEC, while possible through the likes of a VT-125 terminal, were slow, awkward, and very limited, as Fooblitzky had demonstrated all too well. Worse, mixing conventional scrolling text, of the sort needed by an Infocom adventure game, with those graphics on the same screen was all but impossible. Moriarty therefore decided to approach the question from the other side. What graphic or graphic-like things could they accomplish on the PDP-10 without losing the ability to easily display text as well?

That turned out to be, if far from the state of the art, nevertheless more than one might expect, and also much more than was possible at the time that they’d first installed their PDP-10. DEC’s very popular new VT-220 line of text-oriented terminals couldn’t display bitmap graphics, but they could change the color of the screen background and individual characters at will, selecting from a modest palette of a dozen or so possibilities. Even better, they could download up to 96 graphics primitives into an alternate character set, allowing the drawing of simple lines, boxes, and frames, in color if one wished. By duplicating these primitives in the microcomputer interpreters, Infocom could duplicate what they saw on their DEC-connected dumb terminals on the computer monitors of their customers. Like much of the game that would gradually evolve from Moriarty’s thought experiment, this approach marked as much a glance backward as a step forward. Character graphics had been a feature of microcomputers from the beginning — in fact, they had been the only way to get graphics out of two of the Trinity of 1977, the Radio Shack TRS-80 and the Commodore PET — but had long since become passé on the micros in light of ever-improving bitmap-graphic capabilities. Once, at the height of their success and the arrogance it engendered, Infocom had declared publicly that they wouldn’t do graphics until they were confident that they could do them better than anyone else. But maybe such thinking was misguided. Given the commercial pressure they were now under, maybe primitive graphics were better than no graphics at all.

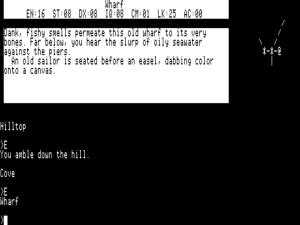

Thus color and character graphics became the centerpieces of a new version of the Z-Machine that Dave Lebling, Chris Reeve, and Tim Anderson, Infocom’s chief technical architects, began putting together for Moriarty’s “experimental” project. This version 5 of the Z-Machine, the last to be designed for Infocom’s PDP-10-based development system, gradually came to also sport a host of other new features, including limited mouse support, real-time support, and the ability, previously hacked rather rudely into the old version 3 Z-Machine for The Lurking Horror, to play sampled sound files. The most welcome feature of all was one of the least flashy: an undo command that could take back your last turn, even after dying. Game size was still capped at the 256 K of the version 4 Z-Machine, a concession to two 8-bitters that still made up a big chunk of Infocom’s sales, the Commodore 128 and the Apple II. For the first time, however, this version of the Z-Machine was designed to query the hardware on which it ran about its capabilities, degrading as gracefully as possible on platforms that couldn’t manage to provide its more advanced features. The graphically primitive Apple II, for instance, didn’t offer color and replaced the unique character-graphic glyphs with rough approximations in simple ASCII text, while both 8-bitters lacked the undo feature. Mouse input and sound were similarly only made available on machines that were up to it. Infocom took to calling the version 5 games, of which Moriarty’s nascent project would be the first, “XZIPs,” the “X” standing for “experimental.” (Even after Moriarty’s game was released and the format was obviously no longer so experimental, the name would stick.)

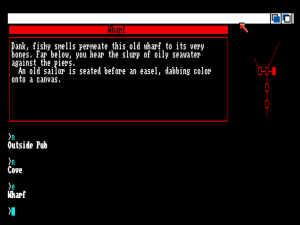

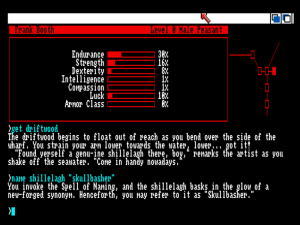

Moriarty’s new interface running on an Amiga. Note the non-scrolling status window at top left that currently displays the room description, and the auto-map at top right. You can move around by clicking on the map as well as by typing the usual compass directions.

Of course, it was still up to Moriarty to decide how to use the new toolkit. He asked himself, “What can I do within the constraints of our technology to make the adventuring experience a little easier?” He considered trying to do away with the parser entirely, but decided that that still wasn’t practical. Instead he designed an interface for what he liked to call “an illuminated text adventure.” Once again, in looking forward he found himself to a surprising extent looking back.

In watching myself play, I found the command I typed most was “look.” So I said this is silly, why can’t the room description always be visible? After all, that’s what Scott Adams did in his original twelve adventures, with a split-screen showing the room description, exits, and your inventory at the top, while you type in the bottom. So I said, let’s take a giant step backward. The screen is split in half in most versions. On the left side of the top half is a programmable window. It can contain either the room description or your inventory. So as you walk from room to room, instead of the description coming in-line with your commands, as it does now in our games, this window is updated. If you say, “inventory,” the window changes to show your possessions.

Another thing I liked about the old Scott Adams games was the list of room exits at the top of the screen. That’s a part of writing room descriptions that has always bugged me: we have to have at least one sentence telling where the exits are. That takes up a lot of space, and there are only so many interesting ways to do that. So I said, let’s have a list of exits at the top. Now, that’s not such a revolutionary idea. I thought of putting in a compass rose and all this other stuff, but finally I came up with an onscreen map that draws a typical Infocom map — little boxes with lines and arrows connecting them. The right side of the upper screen has a little graphics map that draws itself and updates as you walk around. It shows rooms as boxes and lines as their connections. If you open a door, a line appears to the next room. Dark rooms have question marks in them. The one you’re in is highlighted, while the others are outlined.

This onscreen map won’t replace the one you draw yourself, but it does make it much easier to draw. It won’t show rooms you haven’t been to yet, but shows exits of your current room and all the exits of the adjoining rooms that you’ve visited.

There’s even more to this re-imagining of the text adventure. On machines equipped with mice, it’s possible to move about the world by simply clicking on the auto-map; function keys are now programmable to become command shortcuts; colors can be customized to your liking; even objects in the game can be renamed if you don’t like the name they came with. And, aware that plenty of customers had a strong traditionalist streak, Moriarty also made it possible to cut the whole thing off at the knees and go back to a bog-standard text-adventure interface at any time by typing “mode” — although, with exits now absent from room descriptions, it might be a bit more confusing than usual to play that way.

But really, it’s hard to imagine any but the most hardcore Luddites choosing to do so. The new interface is smart and playable and hugely convenient, enough to make you miss it as soon as you return to a more typical text adventure, to wish that it had made it into more than the single Infocom game that would ultimately feature it, and to wonder why more designers haven’t elected to build on it in the many years since Infocom’s demise. Infocom wrote about the new interface in their Status Line newsletter that, “never a company to jump into the marketplace with gaudy or ill-conceived bells and whistles, we have always sought to develop an intelligently measured style, like any evolving author would.” It does indeed feel like a natural, elegant evolution, and one designed by an experienced player rather than a marketeer.

With the new interface design and the technology that enabled it now well underway, Moriarty still needed an actual game to use it all. Here he made another bold step of the sort that was rapidly turning his erstwhile thought experiment into the most ambitious game in Infocom’s history. It began with another open-ended question: “What kind of game would go well with this interface?” He settled on another first for Infocom: still a text adventure, but a text adventure “with very strong role-playing elements,” in which you would have to create a character and then build up her stats whilst collecting equipment and fighting monsters.

I spent a lot of time playing fantasy games like Ultima and Wizardry and, one that I particularly liked a lot, Xyphus for the Macintosh. And I realized it was fun to be able to name your character and have all these attributes instead of having just one number — a score — that says how well you’re doing. I thought it would be nice to adopt some of the conventions from this kind of game, so you don’t have one score, you have six or seven: endurance, strength, compassion, armor class, and so on. Your job in the game is, very much like in role-playing games, to raise these statistics. And your character grows as you progress through the puzzles, some of which cannot be solved unless you’ve achieved certain statistics. You can somewhat control the types of statistics you “grow” in order to control the type of character you have.

In conflating the CRPG with the text adventure, Moriarty was, yet again, looking backward as much as forward. In the earliest days of the entertainment-software industry, no distinction was made between adventure games and CRPGs — small wonder, as text adventures in the beginning were almost as intimately connected with the budding tabletop RPG scene as were CRPGs themselves. Will Crowther, creator of the original Adventure, was inspired to do so as much by his experience of playing Dungeons and Dragons as he was by that of spelunking in Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave. Dave Lebling was a similarly avid Dungeons and Dragons player at the time that he, along with three partners, created the original mainframe Zork, the progenitor of everything that would follow for Infocom. It was Lebling who inserted Dungeons and Dragons-style randomized combat into that game, which survived as the battles with a certain troll and thief that served as many players’ introductions to the perils of life in the Great Underground Empire in Zork I on microcomputers. About the same time, Donald Brown was creating Eamon, the world’s first publicly available text-adventure creation system that also happened to be the first publicly available CRPG-creation system. When Byte magazine made the theme of its December 1980 issue “Adventure,” no editorial distinction was made between games where you wandered around solving puzzles and those where you wandered around killing monsters. Years before Infocom would adopt the term “interactive fiction” as their preferred name for their creations, Lebling described Zork for that issue as a “computerized fantasy simulation,” a term which today smacks much more of the CRPG than the text adventure. In the same issue Jon Freeman, creator of Temple of Apshai and many of its sequels, spent quite some pages laboriously describing his approach to adventuring, which offered “character variation” that “affects the game in many ways.” He struggles, with mixed results, to clarify how this is markedly different from the approach of Zork and Scott Adams. In retrospect, it’s obvious: he’s simply describing the difference between a CRPG and a text adventure. Over time this difference became clearer, even intuitive, but for years to come the two forms would remain linked in gamers’ minds as representing separate sub-genres more so than categories onto themselves. “Adventure-game columnists” like Computer Gaming World‘s Scorpia, for instance, continued to cover both into the 1990s and beyond.

That’s by no means inexplicable. The two forms shared plenty in common, like a story, a love of fantasy settings, and the need to explore a computer-simulated world and (usually) to map it. The forms were also connected in being one-shot games, long experiences that you played through once and then put aside rather than shorter experiences that you might play again and again, as with most action and strategy games of the period. And then there was the simple fact that neither would likely have existed in anything like the form we know them if it hadn’t been for Dungeons and Dragons. Yet such similarities can blind us, as it did so many contemporary players, to some fairly glaring differences. We’ll soon be seeing some of the consequences of those differences play out in Moriarty’s hybrid.

By the time that Moriarty’s plans had reached this stage, it was the fall of 1986, and Infocom was busily lining up their biggest slate of new games ever for the following year. It had long since been decided that one of those games should bear the Zork name, the artistic fickleness that had led the Imps to reject Infocom’s most recognizable brand for years now seeming silly in the face of the company’s pressing need for hits. Steve Meretzky, who loved worldbuilding in general, also loved the lore of Zork to a degree not matched even by the series’s original creators. While working on Sorcerer, he had assembled a bible containing every scrap of information then “known” — more often than not in the form of off-hand asides delivered strictly for comedic effect — about the Flathead dynasty, the Great Underground Empire, and all the rest of it, attracting in the process a fair amount of ridicule from other Imps who thought he was taking it all far, far too seriously. (One shudders to think what they would say about The Zork Compendium.) Now Meretzky was more than eager to do the next Zork game. Whirling dervish of creativity that he was, he even had a plot outline to hand for a prequel, which would explain just how the Great Underground Empire got into the sorry state in which you first find it in Zork I. But there was a feeling among management that the long-awaited next Zork game ought to really pull out all the stops, ought to push Infocom’s technology just as far as it would go. That, of course, was exactly what Moriarty was already planning to do. His plan to add CRPG elements would make a fine fit with the fantasy milieu of Zork as well. Moriarty agreed to make his game a Zork, and Meretzky, always the good sport, gave Moriarty his bible and proceeded to take up Stationfall, another long-awaited sequel, instead.

It was decided to call the new Zork game Beyond Zork, a reference more to its new interface and many technical advancements than to the content of the game proper. Having agreed to make his game a Zork, Moriarty really made it a Zork, stuffing it with every piece of trivia he could find in Meretzky’s bible or anywhere else, whilst recreating many of the settings from the original Zork trilogy as well as the Enchanter trilogy. Beyond Zork thus proclaimed to the world something that had always been understood internally by Infocom: that the Enchanter trilogy in a different reality — a better reality according to marketing director Mike Dornbrook’s lights — could have just as easily shipped as Zork IV through VI. But Moriarty didn’t stop there. He also stuffed Beyond Zork with subtler callbacks to almost the entire Infocom catalog to date, like the platypus, horseshoe, and whistle from Wishbringer and the magical umbrella from Trinity. Mr. Prosser, Arthur Dent’s hapless nemesis from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, shows up as the name of a spell, and Buck Palace, the statuesque B-movie star from Hollywood Hijinx, is the default name for your character if you don’t give him another. There are so many references that upon the game’s release Infocom sponsored a contest to see who could spot the most of them. Especially in retrospect, knowing as we do that we are now coming close to the end of the line for Infocom, all of the backward glances can take on an elegiac quality, can make Beyond Zork feel like something of a victory lap for an entire era of adventure gaming.

I’m less pleased with the actual plot premise of Beyond Zork, which, as unplanned sequels so often tend to do, rather clumsily undermines the message of its predecessor. Moriarty’s game builds on Spellbreaker, which saw you destroying magic in the name of saving the world. The ending of Spellbreaker:

You find yourself back in Belwit Square, all the Guildmasters and even Belboz crowding around you. "A new age begins today," says Belboz after hearing your story. "The age of magic is ended, as it must, for as magic can confer absolute power, so it can also produce absolute evil. We may defeat this evil when it appears, but if wizardry builds it anew, we can never ultimately win. The new world will be strange, but in time it will serve us better."

Strange as it may sound, I judge that jarring last sentence to be nothing less than Dave Lebling’s finest moment as a writer. It’s an ending that can be read to mean many things, from an allegory of growing up and leaving childish things behind to a narrative of human progress as a whole — the replacing of a “God of the gaps” with real knowledge, simultaneously empowering and depressing in the way it can leach the glorious mystery out of life.

But still more depressing is the way that Beyond Zork now comes along to muck it up. You play a novice enchanter (where have we heard that before?) who, even as the wise and powerful hero of Spellbreaker sets about destroying magic, is dispatched by the Guild to retrieve the “Coconut of Quendor” that can safeguard it for a return at some point in the future. Why couldn’t Moriarty just leave well enough alone, find some other premise for his game of generic fantasy adventure? About the best thing I can say about the plot is that you hardly know it’s there when you’re actually playing the game; until the last few turns Beyond Zork is largely a plot-free exercise in puzzles, self-improvement (in the form of easily quantifiable statistics and equipment), and monster bashing.

On those terms, Beyond Zork seems to acquit itself quite well in the early going. Brian Moriarty remains the most gifted prose stylist among the Imps, crafting elegant sentences that must make this game, if nothing else, among the best written generic fantasies ever. Zork always had a bipolar personality, sometimes indulging in unabashed comedy and at others evoking majestic, windy desolation. Perhaps surprisingly in that it comes from the author of the doom-laden Trinity, Beyond Zork leans more toward the former than the latter. But then anyone who’s played Wishbringer knows that Moriarty can do comedy — and the juxtaposition of comedy with darker elements — very well indeed. I particularly like the group of Implementors you meet; this sort of meta-comedy was rapidly becoming another Zork tradition, dating back to the appearance of the adventurer from the original trilogy in Enchanter or, depending on how you interpret the ending of Zork III, possibly even earlier. Moriarty lampoons the reputation the Imps had within Infocom, usually expressed jokingly but not always without an edgy undercurrent, of being the privileged kids who always got all the free lunches and other perks, not to mention the public recognition, while the rest of the company, who rightfully considered themselves also very important to Infocom’s success, toiled away neglected and anonymous.

Ethereal Plane Of Atrii, Above Fields

The thunderclouds are compressed into a flat optical plane, stretching away below your feet in every direction.

A group of Implementors is seated around a food-laden table, playing catch with a coconut.

One of the Implementors notices your arrival. "Company," he remarks with his mouth full.

A few of the others glance down at you.

>x coconut

It's hard to see what all the fuss is about.

A tall, bearded Implementor pitches the coconut across the table. "Isn't this the feeb who used the word 'child' a few moves ago?" he mutters, apparently referring to you. "Gimme another thunderbolt."

>get coconut

The Implementors won't let you near.

A cheerful-looking Implementor catches the coconut and glares down at you with silent contempt.

"Catch!" cries the cheerful-looking Implementor, lobbing the coconut high into the air.

"Got it." A loud-mouthed Implementor jumps out of his seat, steps backwards to grab the falling coconut... and plows directly into you.

Plop. The coconut skitters across the plane.

>get coconut

As you reach towards the coconut, a vortex of laughing darkness boils up from underfoot!

"More company," sighs the cheerful-looking Implementor.

You back away from the zone of darkness as it spreads across the Plane, reaching out with long black fingers, searching, searching...

Slurp! The coconut falls into the eye of the vortex and disappears, along with a stack of lunch meat and bits of cutlery from the Implementors' table. Then, with a final chortle, the vortex draws itself together, turns sideways and flickers out of existence.

"Ur-grue?" asks the only woman Implementor.

"Ur-grue," nods another.

>ask implementors about ur-grue

"I think I just heard something insignificant," remarks an Implementor.

"How dull," replies another, stifling a yawn.

"This is awkward," remarks a loudmouthed Implementor. "No telling what the ur-grue might do with the Coconut. He could crumble the foundations of reality. Plunge the world into a thousand years of darkness. We might even have to buy our own lunch!" The other Implementors gasp. "And it's all her fault," he adds, pointing at you with a drumstick.

"So," sighs another Implementor, toying with his sunglasses. "The Coconut is gone. Stolen. Any volunteers to get it back?"

One by one, the Implementors turn to look at you.

"I'd say it's unanimous," smiles the cheerful-looking Implementor.

A mild-mannered Implementor empties his goblet of nectar with a gulp. "Here," he says, holding it out for you. "Carry this. It'll keep the thunderbolts off your back."

>get goblet

The Implementor smiles kindly as you take the goblet. "And now you will excuse us. My fellow Implementors and I must prepare for something too awesome to reveal to one as insignificant as you."

At first, the CRPG elements seem to work better than one might expect. Randomized combat in particular has for many, many years had a checkered reputation among interactive-fiction fans. It’s very difficult to devise a model for combat in text adventures that makes the player feel involved and empowered rather than just being at the mercy of the game’s random-number generator. There weren’t many fans of the combat in Zork I even back in the day, prompting Infocom to abandon it in all of their future games; only the usually pointless “diagnose” command remained as a phantom limb to remind one of Zork‘s heritage in Dungeons and Dragons. Even Eamon as time went by moved further and further away from its original incarnation as a sort of text-only simulation of Dungeons and Dragons, its scenarios beginning to focus more on story, setting, and puzzles than killing monsters.

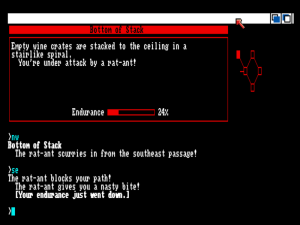

Battling a rat-ant (say, is that a Starcross reference?) in Beyond Zork.

Beyond Zork doesn’t entirely solve any of the problems that led to those developments, but it does smartly make the process of preparing for the combats more compelling than the combats themselves can possibly be. As you explore the world and solve puzzles, you level up and improve your ability scores. Among other things, this lets you fight better. You can also sell treasure for money, a nice twist on the treasure-hunt model of old-school text adventuring, and use it to buy better weapons, armor, and magic items. As you improve yourself through these means and others, you find that you can challenge tougher monsters. Thus, while the combat is still not all that interesting in itself — it still comes down to the same old “monster hits you for X points of damage, you hit monster for Y points of damage,” rinse and repeat until somebody is done for — the sudden ability to win a battle in which you previously didn’t have a chance can feel surprisingly rewarding. Many of the monsters take the place of locked doors in more conventional text adventures, keeping you out of places you aren’t yet ready for. It feels about as satisfying to defeat one of these as it does to finally come across the key for a particularly stubborn lock in another game. Indeed, I wish that Moriarty had placed the monsters more carefully in order to guide you through the game in the right order and keep you from locking yourself out of victory by doing the right things in the wrong order, as I’ll describe in more detail shortly.

It also helps that the combats are usually quite low-stakes. While undo is disabled in combat — how ironic that Infocom introduced undo in their first game ever with a good reason not to allow it! — it’s always obvious very quickly when you’re over-matched, and usually fairly trivial to back away and go explore somewhere else before you get killed. One other subtle touch, much appreciated by a big old softie like me who can even start to feel bad for the monsters he kills in Wizardry, is that you rarely actually kill anything in Beyond Zork. Monsters usually “retreat into the darkness” or something similar rather than expiring — or at least before expiring. While I suspect Moriarty did this more to avoid implementing dead monster bodies than to make a statement, I’ll take my instances of mercy wherever I can find them.

Beyond Zork blessedly doesn’t take itself all that seriously, whether as a CRPG or as anything else. Instead of the painfully earnest orcs and dragons that populate most CRPGs, Beyond Zork‘s monsters are almost uniformly ridiculous: Christmas tree monsters singing dreadful carols (anyone who’s ever visited a shopping mall on Black Friday can probably relate), cruel puppets who attack by mocking you (they “recite your nightly personal habits in excruciating detail” among other attacks), dust bunnies (got any lemony-fresh Pledge handy?). In a sense Beyond Zork is just another genre exercise for Infocom, albeit in a ludic rather than a literary genre this time, and as usual for them it can sometimes feel as much parody as homage. There are alternate, puzzlely solutions that can be used to defeat many monsters in lieu of brute strength, and usually in more entertaining fashion at that. In fact, in many cases cleverness is the only way forward. Vital clues to the various monsters’ weaknesses are found in the game’s version of Dungeons and Dragons‘s Monster Manual, the accompanying feelie “The Lore and Legends of Quendor”; if only other companies offered such entertaining and clever copy protection! And if fighting fair and square or puzzling your way around the monsters aren’t enough alternatives for you, you can just use your Wand of Annihilation or other magic. Not just monsters but also many other problems can similarly be defeated in various ways. Beyond Zork is surprisingly flexible.

But, sadly, it’s often dangerously flexible. Which brings us to the part of this article where I have to tell you why, despite its many innovations, despite Moriarty’s usual fine writing, and despite some fine puzzles, Beyond Zork in my opinion just doesn’t add up to all that great of a game. I think I can best explain how things go wrong by dissecting one particularly dismaying sequence in some detail.

Fair warning: heavy spoilers begin here!

So, I come upon a mother and baby hungus — “part sheep, part hippopotamus,” as “The Legends and Lore of Quendor” helpfully tells us — caught in a bad situation.

Quicksand

A strip of dry path winds alongside a pool of quicksand. You see a baby hungus stuck into the wet, gritty surface.

A mother hungus is standing nearby, gazing anxiously at her baby.

Luckily, I happen to have found a Stave of Levitation. What I need to do seems pretty obvious.

>point stave at baby

The baby hungus bellows with surprise as he rises out of the quicksand! Sweat breaks out on your forehead as you guide the heavy burden over the mud and safely down to the ground.

[Your strength just went down.]

The ungainly creature nuzzles you with his muddy snout, and bats his eyelashes with joy and gratitude. Then he ambles away into the jungle to find his mother, pausing for a final bellow of farewell.

[Your compassion just went up.]

Heartwarming, isn’t it? But you know what’s less heartwarming? The fact that I’ve just locked myself out of victory, that’s what. I needed to do something else, which we’ll get to in a moment, before rescuing the little fellow. It will, needless to say, likely be a long, long time before I realize that, especially given that the game actually rewards me by increasing my Compassion score. (As for the Strength loss, never fear, I’ll recover that automatically in a few turns.) This is terrible design, of the sort I expect from early Sierra, not late Infocom. I wrote in an earlier article that “we should reserve a special layer of Hell for those designs whose dead ends feel not just like byproducts of their puzzles and other interactive possibilities but rather intentional traps.” See you down below, Beyond Zork.

Beyond Zork is absolutely riddled with these sorts of traps, forcing you to restart many, many times to get through it, wondering all the while whether you didn’t render this latest puzzle you’re wrestling with insoluble a long time ago by some innocent, apparently correct action like the one above. What makes this even more baffling is that in other ways Beyond Zork is presented as an emergent, replayable experience, the sort of game where you take your lumps and move on until you either win or lose rather than constantly restoring and/or restarting to optimize your play. Taking a cue from the roguelike genre, large chunks of Beyond Zork‘s geography are randomly generated anew every time you play, as are the placement of most magic items and their descriptions; that Stave of Levitation I just used may be a Stave of Annihilation in another playthrough, forcing me to make sure I make good use of the various shops’ ability to identify stuff for me. As the manual tells you, “No two games of Beyond Zork are exactly alike!” But what’s the point of that approach when most of those divergent games leave you fruitlessly wandering about, blocked at every turn, wondering where you went wrong? Even an infamously difficult roguelike like NetHack at least puts you out of your misery when you screw up. By the time you do figure out how to tiptoe through this minefield of dead ends, you’ve internalized the whole game to such an extent that the randomness is just a huge annoyance.

The deterministic text adventure and the emergent CRPG end up rubbing each other raw almost every time they touch. When you discover a cool new magic wand or spell, you’re afraid to use it to vanquish that pesky monster you’ve been struggling with for fear that you’ll need to use it to solve some deterministic puzzle somewhere else. Yes, resource management was always a huge part of old-school dungeon crawls like Wizardry and The Bard’s Tale — arguably the hugest part, given that their actual combat engines were often little more sophisticated than that of Beyond Zork — but there was always a clear distinction between things you might need to solve puzzles and things for managing combat. The lack of same here is devastating; the CRPG aspects are really hard to enjoy when you’re constantly terrified to actually use any of the neat equipment you collect.

And just as the text adventure undermines the CRPG, the CRPG also undermines the text adventure. Near the hungi — never fear, we’ll return to that problem shortly! — I find this, yet another callback to Spellbreaker:

>w

Idol

A stone idol, carved in the likeness of a giant crocodile, stands in a clearing.

You see a tear-shaped jewel in its gaping maw.

You see a tear-shaped jewel on the idol's maw.

>x idol

This monstrous idol is approximately the size and shape of a subway train, not counting the limbs and tail. The maw hangs wide open, its lower jaw touching the ground to form an inclined walkway lined with rows of stone teeth. A tear-shaped jewel adorns the idol's face, just below one eye.

>enter idol

You climb up into the idol's maw.

The stone jaw lurches underfoot, and you struggle to keep your balance. It's like standing on a seesaw.

>get jewel

The idol's maw tilts dangerously as you reach upward!

Slowly, slowly, you draw your hand away from the tear-shaped jewel, and the jaw settles back to the ground.

>u

You edge a bit further into the open maw.

Creak! The bottom of the jaw tilts backward, pitching you helplessly forward...

This sequence begins a veritable perfect storm of problems, starting with the text itself, which contradicts itself and thus makes it hard to figure out what the situation really is. Is the jewel in the idol’s maw, on the idol’s maw (the weird doubled text is present in the original), or stuck to the idol’s face? Or are there two jewels, one stuck on his face and one in (on?) his maw? I’m still not sure. But let’s continue a bit further.

>turn on lantern

Click. The lantern emits a brilliant glow.

Inside Idol

This long, low chamber is shaped much like the gizzard of a crocodile. Trickles of fetid moisture feed the moss crusting the walls and ceiling.

>squeeze moss

The moss seems soft and pliant.

The moss is “Moss of Mareilon.” As described in “The Lore and Legends of Quendor,” squeezing it as I’ve just done will lead to a dexterity increase a few turns from now. And so we come to one of the most subtly nasty bits in Beyond Zork. To fully explain, I need to back up just a little.

Earlier in the game, in a cellar, I needed to climb a “stairlike spiral” of crates to get something on top of them. Alas, I wasn’t up to it thanks to a low dexterity: “You teeter uncertainly on the lowest crates, lose your balance, and sprawl to the ground. Not very coordinated, are you?” Luckily, some Moss of Mareilon was growing right nearby; I could squeeze it to raise my dexterity enough to get the job done.

So, when I come to the idol, and find more Moss of Mareilon growing conveniently just inside it, that combined with the description of my somewhat clumsy effort to grab the jewel leads to a very natural thought: that I need to squeeze the moss inside the idol to increase my dexterity enough to grab the jewel. I do so, then use a handy magic item to teleport out, then do indeed try again to grab the jewel. But it doesn’t work; I still can’t retrieve the jewel, still get pitched down the idol’s throat every time. After struggling fruitlessly with this poorly described and poorly implemented puzzle — more on that in a moment — I finally start thinking that maybe it can’t be solved because I didn’t give my character enough dexterity at the very beginning of the game. This can actually happen; Beyond Zork is quite possibly the only text adventure ever written in which you can lock yourself out of victory before you even enter your first command. (“The attributes of the ‘default’ [pre-created] characters are all sufficient to complete the story,” says the manual, which at least lets you know some of what you’re in for if you decide to create your own.) So, I create a brand new character with very good dexterity, and spend an hour or so, cursing all of the randomizations all the while, to get back to the idol puzzle. But I still can’t fetch the diamond, not even after squeezing the moss.

It does seem that the game has, once again, actively chosen to mislead me and generally screw me over here. But, intentionality aside, a more subtle but more fundamental problem is the constant confusion between player skill, the focus of a text adventure, and character skill, the focus of a CRPG. Let me explain.

A text adventure is a much more embodied experience than a CRPG. There’s a real sense that it’s you — or, increasingly in later games, a character that you are inhabiting — whom you are guiding through the simulated world. Despite the name, meanwhile, a CRPG is a more removed experience. You play a sort of life coach guiding the development of one or more others. Put another way, one genre emphasizes player skill, the other character skill. Think about what you spend the most time doing in these games. The most common activity in a text adventure is puzzle-solving, the most common in a CRPG combat. The former relies entirely on the wit of the player; the latter, if it’s done well, will involve plenty of player strategy, but it’s also heavily dependent on the abilities of the characters you guide. After all, no amount of strategy is going to let you win Wizardry or The Bard’s Tale with a level 1 party. CRPGs are process-intense simulations to a greater degree than text adventures, which rely heavily on hand-crafted content, often — usually in these early years — in the form of puzzles of one stripe or another. This led Jon Freeman in his Byte article to call text adventures, admittedly rather reductively, not simulations or even games at all but elaborate puzzle boxes built out of smaller puzzles: “It can be quite challenging to find the right key, the right moment, and the right command to insert it in the right lock; but once you do, the door will open — always.” In a CRPG, on the other hand, opening that lock might depend on a random number and some combination of a character’s lock-picking ability, the availability of a Knock spell, and/or the quality of the lock picks in her pack. More likely, the locked door won’t be there at all, replaced with some monster to fight. Sure things aren’t quite so common.

Of course, these distinctions are hardly absolute. CRPGs, for example, contained occasional player-skill-reliant puzzles to break up their combat almost from the very beginning. Muddying up the player-skill/character-skill dichotomy too much or too thoughtlessly can, however, be very dangerous, as Beyond Zork has just so amply demonstrated. While one hardly need demand an absolutely pure approach, one does need to know where the boundaries lie, which problems you can solve by solving a puzzle for yourself and to which you need to apply some character ability or other. Those boundaries are never entirely clear in Beyond Zork, and the results can be pretty ugly.

All that said, I still haven’t actually solved the idol puzzle. I guessed quite quickly that the description of standing on the idol’s maw as “like standing on a seesaw” was a vital clue. The solution, then, might be to place a counterweight at the front of the maw to keep it from pitching up and pitching me in. Yet the whole thing is so sketchily described and implemented that I remain unsure what’s actually happening. If I start piling things up inside the maw, they do fall down into the idol’s stomach along with me when I reach for the jewel — apparently, anyway; they’re not described as falling with me, but they do show up in the stomach with me once I get there. But if those things fall through, why not the jewel? If it’s sitting on the idol’s tongue, it’s hard to imagine why it wouldn’t. Or is it actually stuck to the idol’s face, and the stuff about it being in the maw is all a big mistake? Yes, we’re back to that question again. It’s worth noting that the quicksand area and the hungi therein are similarly subtly bugged. If I rescue the baby before doing something with the mother, he’s described as “ambling away into the jungle to find his mother” even though she’s right there, and, since I’ve just hopelessly screwed up, will now remain there forevermore.

The solution to the idol puzzle is clued in “The Lore and Legends of Quendor.” A hungus, it says, “will instantly charge at anything that dares to threaten its kin.” I have to attack the baby hungus and make use of the mother’s rage before rescuing her son.

>attack baby

[with the battleaxe]

Your battleaxe misses the baby hungus. It's just beyond your reach.

A sound like a snorting bull turns your attention to the mother hungus. It looks as if she's about to attack!

The mother hungus charges you. Ooof!

[Your endurance just went down.]

The baby hungus bellows helplessly, and its mother responds.

>ne

The baby hungus bellows mournfully as you walk away.

Birdcries

The unnerving cries of exotic birds echo in the treetops.

>z

Time passes.

The mother hungus storms into view!

>s

Idol

A stone idol, carved in the likeness of a giant crocodile, stands in a clearing.

You see a tear-shaped jewel in its gaping maw.

You see a tear-shaped jewel on the idol's maw.

>z

Time passes.

The mother hungus storms into view!

[Your endurance is back to normal.]

>enter maw

You climb up into the idol's maw.

The stone jaw lurches underfoot, and you struggle to keep your balance. It's like standing on a seesaw.

The mother hungus clambers onto the bottom of the idol's maw, snorting with rage!

>get jewel

The idol's maw tilts dangerously as you reach upward, standing on tiptoe to grasp the sparkling treasure...

Got it! The jewel pops off the idol's face, slips from your grasp and rolls down to the mother hungus's feet, where she promptly eats it, turns and lumbers off the jaw.

Creak! The bottom of the jaw tilts backward, pitching you helplessly forward...

Getting the jewel out of the hungus is another puzzle, but a much better one, so I won’t spoil it here. (No, it doesn’t involve a laxative…)

Spoilers end.

The sequence I’ve just described is probably the ugliest in the game, but other parts suffer to a greater or lesser degree from many of the same problems. Many of the bugs and textual confusions can doubtless be laid at the feet of an overambitious release schedule, while some of the sketchy implementation is likely down to the space limitations of even the 256 K Z-Machine. In recent correspondence with another Infocom aficionado, we talked about how Trinity, another 256 K game, really doesn’t feel all that huge, how much of the extra space was used to offer depth in the form of a larger vocabulary, richer text, and more player possibility rather than breadth in the form of more rooms and puzzles. Beyond Zork, by contrast, does feel quite huge, marks the most overstuffed game that Infocom had yet released. Considering that it must also support a full-fledged, if simplistic, CRPG engine, depth was quite obviously sacrificed in places.

But Beyond Zork‘s most fundamental failing is that of just not knowing what it wants to be. In an effort to make a game that would be all things to all people, the guaranteed hit that Infocom so desperately needed, Moriarty forgot that sometimes a game designer needs to say, no, let’s save that idea for the next project. Cognitive dissonance besets Beyond Zork from every angle. The deterministic, puzzle-oriented text adventure cuts against the dynamic, emergent CRPG. The cavalcade of in-jokes and references to earlier games, catnip for the Infocom hardcore, cuts against appealing to a newer, possibly slightly younger demographic who are fonder of CRPGs than traditional text adventures. The friendly, approachable interface cuts against a design that’s brutally cruel — sometimes apparently deliberately so, sometimes one senses (and this is in its way more damning to Brian Moriarty as a designer) accidentally so. Beyond Zork stands as an object lesson in the perils of mixing ludic genres willy-nilly without carefully analyzing the consequences. I want it to work, love many of the ideas it tries to implement. But sadly, it just doesn’t. It’s a bit of a mess really, not just difficult, which is fine, but difficult in all the wrong, unfun ways. Spellbreaker is a perfect example of how to do a nails-hard text adventure right. Beyond Zork, its parallel in the Zorkian chronology, shows how to do it all wrong. I expect more from Infocom, as, based on Wishbringer and Trinity, I do from Brian Moriarty as well.

Despite receiving plenty of favorable reviews on the basis of its considerable surface appeal, Beyond Zork didn’t turn into the hit that Infocom needed it to become. Released in October of 1987, it sold a little over 45,000 copies. Those numbers were far better than those of any of the other Infocom games of 1987, proof that the Zork name did indeed still have some commercial pull, but paled beside the best sellers of previous years, which had routinely topped 100,000 copies. Enough, combined with the uptick in sales of their other games for the Christmas season, to nudge Infocom into the black for the last quarter of 1987, Beyond Zork wasn’t enough to reverse the long-term trends that were slowly strangling them. Moriarty himself left Infocom soon after finishing Beyond Zork, tempted away by Lucasfilm Games, whose own adventure-gaming star was rising as Infocom’s fell, and where he would at last be able to fulfill his ambition to dump the parser entirely. We’ll be catching up with him again over there in due time.

(Sources: As usual with my Infocom articles, much of this one is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Other sources include the book Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; Byte of December 1980; Questbusters of August 1987 and January 1988; Commodore Magazine of March 1988.

Beyond Zork is available for purchase as part of The Zork Anthology on GOG.com.)

Brian Moriarty

November 6, 2015 at 2:40 pm

Mia culpa.

However, if my aging memory can still be trusted, the default character name was not Buck Palace. It was Frank Black, named after the character (played so memorably by Dennis Hopper) in the David Lynch film BLACK VELVET, which was released early in production.

Matthew Murray

November 6, 2015 at 3:09 pm

I just replayed this game (for the first time in like 20 years) a month ago. The default character name is Frank Booth.

Bob Reeves

November 6, 2015 at 5:37 pm

Actually it’s Frank Booth, in the game and the movie. You’re thinking of the Pixies, maybe. Anyway, thanks for a great game despite Jimmy’s mostly just criticisms.

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2015 at 5:48 pm

Yes and no. :) If you take the default character his name is indeed Frank Booth. (Not, as Bob noted, Frank Black of the Pixies, although that would have been fun too.) However, if you make your own character and make him male the default name, which you can change if you like, is Buck Palace.

Matthew Murray

November 6, 2015 at 9:22 pm

That’s just not correct in the version of the game I have. No matter what you to do to create a male character, it’s always Frank Booth. Never Buck Palace.

Nathan

November 7, 2015 at 7:27 am

It’s Buck Palace in versions 47 and 49, Frank Booth in 51 and 57.

Brian Moriarty

November 7, 2015 at 4:19 pm

Ahem. Make that BLUE VELVET.

Hanon Ondricek

November 6, 2015 at 3:47 pm

I loved Beyond Zork for its replayability.

Quick typo:

About the best thing I can say about the plot is that you hardly knows it’s there when you’re actually playing the game

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2015 at 5:51 pm

Thanks!

Torbjörn Andersson

November 10, 2015 at 3:55 pm

This sounds a bit odd to me:

“It does seems that the game has, once again, actively …”

I’m not a native English speaker, but should that be either “It does seem” or “It seems”?

Jimmy Maher

November 10, 2015 at 6:07 pm

Yes, it should. Thanks!

doug egan

November 6, 2015 at 4:34 pm

Jimmy,

Maybe you, or one of your readers, can answer a question that has dogged me for years. I played Infocom games on my C64 in the early to mid 80s. I had a piece of software at that time called “Disc Doctor” that allowed me to scan discs by block and sector. I swear I read every block and sector of the Zork I disk looking for ascii characters. The only ones I ever found were “saving” and “loading” type message

After failing to find any ascii, I starting thinking like a cryptographer and looking for patterns that might have represented coded text. Still nothing.

So how was the text encoded on the discs? Would it ever have been possible for me to read text directly from the disc, or was it coded in a way that would have made that effectively impossible?

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2015 at 5:54 pm

Infocom’s text was stored in a format they called ZSCII. It permitted them to store 3 characters for every 2 bytes of space, and had the additional virtue, as you discovered, of making the text impossible to read with a sector editor or hex editor. Everything you could possibly want to know about the format is here: http://inform-fiction.org/zmachine/standards/z1point1/sect03.html.

Donnie

November 9, 2015 at 6:16 pm

I remember somehow figuring out how those characters were stored when I was in high school. I didn’t know the slightest thing about virtual machines, but I had some kind of suspicion of it. It was very exciting to finally see all that Infocomish text scrolling down the screen of my Commodore 64.

Matt Reichert

November 6, 2015 at 4:51 pm

First of all let me say that Beyond Zork is my favorite Infocom text adventure hands down. The humor and writing style are right up my alley, I still have a homemade Christmas Tree Monster that I pull out around Christmas time and place next to the regular tree.

I thought the CRPG addition to the standard text adventure was a stroke of genius. It really adds a new dimension to the then aging plain text adventure. The fact that the game is never truly the same twice is a huge plus to me as I like to replay BZ at least once a year and even though I know the answers to all the puzzles it still seems a little fresh. In fact I still find new things in the game each time I play like that Tasting the nectar coating in the goblet increases your luck or wearing the cloak lets you always run away from enemies. It’s little things like this that make BZ one of my favorite games to this day. I still like to see how much I can max out my stats when I play. I wonder if anyone has made a list of all the things in the game that can affect your stats?

Actually that cloak caused a bit of a problem for me back in the day. I knew you had to lead the mother Hungus to the idol to get the jewel out (I cheated and looked up to solution as that puzzle was TOUGH), but she can’t follow you if you have the cloak on. I thought there was some sort of bug in the game and had to restart. I was able to solve the puzzle because I did it before getting my hands on the cloak, but I didn’t know that was the cause of the problem until years later.

BTW the default name is Frank Booth (not Black). I’ve never seen Black Velvet and never knew where that name came from until just now. Another mystery solved.

Hanon Ondricek

November 6, 2015 at 7:50 pm

I must see this Blue/Black Velvet movie starring Frank/Buck Booth/Black/Palace that Brian Moriarty made!

Hunter

May 26, 2016 at 10:07 pm

I’m also a huge Beyond Zork fan. I wish there were more text games like it.

TsuDhoNimh

November 6, 2015 at 5:17 pm

Something that’s even more frustrating about the Idol Jewel puzzle is that, at least on the Apple IIgs version, it is not even necessary to win the game, if you’re willing to take advantage of a bug in the store.

(possible spoilers below)

For some reason, you could sell the butterfly at the store for a small amount, and then leave the store. The butterfly would fly back out to eat the nectar on the goblet. You could then go in and sell it again for double the price as before. Repeat this about five or six times, and you have enough money to buy everything you need in the store without having to get and then sell the jewel.

I was also frustrated that you couldn’t just blast the idol with the staff of Destruction to get the jewel or use the staff of Levitation to get it.

I enjoyed this game perhaps more than it deserved back in the day. At the time I was still a big fan of Eamon and was excited that Infocom had finally tried to make an RPG.

Markus

November 6, 2015 at 5:25 pm

“Buck Palace” is the default name in the early version, later it’s “Frank Booth”. Do the bugs and idiosynchracies as mentioned appear in later versions as well? That said, the Beyond Zork interpreter evolves a bit as well, version A is slightly less sophisticated than, say, version J.

And hey, no mention of other Beyond Zork interpreter specifics, such as the MODE and STATUS commands, and MONITOR, and COLOR, NAME, PRIORITY, OOPS, REFRESH, and uh…

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2015 at 6:09 pm

As noted elsewhere, I don’t believe the default character names change between versions. I played the first released version, serial number 870917. Beyond Zork did get an unusual number of updates for a late-period Infocom game, three of them. One would certainly hope these fixed some of the minor glitches, but I’m sure the more fundamental problems — or what I consider to be fundamental problems, anyway :) — remained. (It’s also possible that some of these releases were not updates at all but just versions for different platforms. Infocom’s cross-platform ideal was starting to get a little more threadbare by this point, in spite of the attempts to built more flexibility into the version 5 Z-Machine.)

Matt Reichert

November 6, 2015 at 6:14 pm

On the Apple II version (which was the one I had) it was always Frank Booth. Even when you made a character (which I always did) it said Frank Booth. I never saw Buck Palace as the name.

Markus

November 6, 2015 at 11:41 pm

Checked it quickly, it seems to be “Buck” in in 47/870915 and 49/870917, and “Frank” in 51/870923 and 57/871221. Changing the interpreter and/or platform – in Frotz or for real – doesn’t seem to have an impact except for the obvious front-end aspects (colors and all). To figure out how this is coded in(to) the story file I’d have to undust my (already limited) skills in using Disinform, do I really want to do that? Hm…

There seems to be no female default name. If you, say, choose a preset character and opt for female, it still offers only Buck (or Frank).

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2015 at 11:43 pm

I guess that settles that then. Thanks for taking the time to check it out!

Markus

November 6, 2015 at 5:31 pm

Sorry, you do mention MODE. Right. Not enough coffee.

S. John Ross

November 6, 2015 at 7:17 pm

I don’t know if it’s obvious (it’s MEANT to be obvious, but I may have botched that aspect) but the game Treasures of a Slaver’s Kingdom is _about_ is Beyond Zork, both in terms of celebrating it and (in some small areas) building upwards from it. Beyond Zork is, despite its occasional difficulties, tied for favorite among the Infocom games (tied with LGoP), and I still return to it for comfort, inspiration, and renewal of purpose. Where Tolkien and Howard and others failed to make fantasy “click” for me, Beyond Zork succeeded (it’s also the tonal parent of Uresia: Grave of Heaven, and I even contacted the BZ cartographer to do graphic work for me; I just couldn’t afford him)!

Matt Wigdahl

November 6, 2015 at 10:42 pm

In retrospect the many mechanical similarities and in-game homages should have been obvious, but I missed it at the time, being completely sucked in by your alternate-reality CogniKing/Encounter Critical meta-backstory.

If there are folks reading this that enjoyed Beyond Zork, you will almost certainly enjoy Treasures of a Slaver’s Kingdom.

S. John Ross

November 7, 2015 at 12:24 am

Aw, thank you Mr. Wigdahl =)

And I get pretty sucked into the meta-backstory myself. The ratio of irony to sincerity in that game leans a lot more sincere than I should ever explicitly admit to …

matt w

November 7, 2015 at 4:53 am

I haven’t played Beyond Zork, but as soon as I read Jimmy’s description of the monsters as gates, I thought “Ooh, just like S. John did in Treasures of a Slaver’s Kingdom!” So in its odd way it was obvious to me.

And yes, enthusiastic second for the Treasures of a Slaver’s Kingdom recommendation.

S. John Ross

November 8, 2015 at 9:30 am

Sa-ho!

Jimmy Maher

November 7, 2015 at 8:36 am

I never made that connection either, although I enjoyed Treasures a lot. If I remember correctly, it focuses much more on the combat and doesn’t try to offer puzzles of anywhere near the complexity of Beyond Zork. Perhaps for that reason I found it very playable and solvable. And, yes, hugely entertaining with the backstory that practically reeks of nerdy 1980s kids playing D&D for hours on end in their parents’ basement (not necessarily a smell you want to experience in real life, believe me). In short, count me as another enthusiastic thumbs-up!

S. John Ross

November 8, 2015 at 9:30 am

Thank you, sir =) And yeah, Treasures isn’t really interested in Zork-level lateral thinking, partly because I’m personally bad at SOLVING such puzzles, and partly because it would clash with the tone of Encounter Critical and (I suspect) discourage the EC fans I built it for, who are, as a group, AWARE of text-adventures but with highly variable levels of investment in the form. I was sincerely shocked when Real Actual IF Enthusiasts also liked it.

Duncan Stevens

November 6, 2015 at 7:47 pm

Much as I enjoyed Beyond Zork back in the day, I mostly agree with Jimmy’s criticisms now. But I would characterize BZ more as a fairly good text adventure with some less-successful CRPG elements here and there, and while there are some bad design aspects, they’re not usually the CRPG elements’ fault, as such; they’re just poor design choices. The hungus puzzle is probably the worst example; the other bad choices are more in the category “event that occurs only once, and there’s a good chance you won’t realize its significance the first time,” like the minx and pterodactyl. Put another way: the deterministic aspect you describe interferes with the CRPG play because the player is reluctant to use resources (and, in at least one instance, may be inclined to keep bashing away at monsters when there was a puzzle-style way of getting rid of them), but the character-skill-building aspects don’t interfere with the text-adventure play. At least, they didn’t for me; the idea that the moss was the solution to the jewel puzzle never occurred to me, and I can’t think of any other times when I thought a problem would be solved with more skill. (And it wasn’t that I just didn’t play CRPGs, so the idea didn’t occur to me. I had played all the Wizardry games that had come out to that point.) The finite-use items didn’t bother me in the puzzle-solving–for whatever reason, I felt pretty confident that I wasn’t overusing them (perhaps because when I did use them, they appeared to be one of several potential solutions, such as the unicorn-in-the-stall puzzle).

(Interestingly, the fellow behind the CRPG Addict blog, who has systematically been working through CRPGs and has now made it up to 1990 or so, played Beyond Zork a while back and enjoyed it, surprisingly to me. First of several posts. He did say in the first post that he enjoyed text adventures, but not as much as CRPGs; considering that BZ works much better as a text adventure than as a CRPG, I’d have expected him to be lukewarm at best.)

On the design, there was good and bad. The triggers worked for the Wizard-of-Oz-parody bit, where (as I recall) you wouldn’t be sent to get a vital object until you knew what you would be looking for. It quickly became apparent to me that most of the magic was redundant: you could solve things with magic a lot of different ways (see the unicorn again). I was less enamored of the Zeno’s-bridge puzzle, which wasn’t actually a puzzle that could be solved (and when I encountered a dispel staff, it seemed like it should have worked; it didn’t), and as funny as the idea of the cruel puppet was, I was expecting a Scroll of Indifference or some such thing that would defeat him in a similarly creative way, but no. I’d say there were some quite good, and generally fair, puzzles–helmet/hourglass, dorn, cliff riddle, volcano/caterpillar, mirrors/darkness–mixed in with some bad ones, of which the idol puzzle was undoubtedly the worst.

Jimmy Maher

November 7, 2015 at 8:24 am

For me, the Zeno’s Bridge puzzle is an example of the expectations of the text adventure and the CRPG conflicting. You expect these magic items to work consistently everywhere, in harmony with the more emergent, simulation-oriented approach of a CRPG. But they just don’t, and it’s hard to figure out where the boundaries lie, hard to know what’s a set-piece, deterministic puzzle and what’s a more flexible piece of world model. There are puzzles — or maybe one should say “situations” — like the unicorn that are admirably flexible, but there are others like the idol that are specific and persnickety. Even taking the idol puzzle on its own terms, it would have been nice if it was possible for me to just pile enough stuff inside the mouth to offset my own weight. But this doesn’t work; the simulation doesn’t go far enough. Likewise, it would have been nice if a character with really high dexterity, regardless of how it was acquired, could leap to safety.

I don’t think Beyond Zork is an irredeemable design at all. If I was making the game today, I would include a manager to make sure you can’t lock yourself out of victory: drop another magic item into the land somewhere if you use up something vital, etc. The game could still be a challenge, since you’d still need to find that item and figure out how to use it, but it wouldn’t be so cruel as what we have now. And I would push the simulation much further: give every item a weight for handling the idol puzzle, more use of ability scores to make playing with different characters feel more unique, etc. In other words, I like much of what Beyond Zork is trying to do, I just wish it did it *more* and more consistently. But obviously Infocom was never going to be able to add this complexity to a game that was already pushing the limits of the Z-Machine’s resources. This may be a failure, to whatever extent it is one — as shown by the comments here, opinions vary on this score — caused more by overambition in the face of technical constraints than anything else. Definitely an idea I’d like to see revisited.

S. John Ross

November 6, 2015 at 7:52 pm

On reflection, my only real complaint with this excellent article is: not a single word for Bruce Hutchison?

Jimmy Maher

November 7, 2015 at 8:09 am

Just following Infocom’s lead: https://www.filfre.net/misc/bz.png

S. John Ross

November 8, 2015 at 9:17 am

Fair, but … sigh =)

I know when you write about Infocom and graphics it’s about the _computer_ graphics, but Hutchison’s work on the feelies is a huge part of the beauty of BZ, I think, and I’d love to learn more about his involvement someday. I guess I could just pester him myself, but I’m happy letting you do all the journalism while I just sit back and read =)

ZUrlocker

November 9, 2015 at 4:59 pm

Who is Bruce Hutchison?

Jimmy Maher

November 10, 2015 at 7:59 am

Drew the decorative map included as a feelie.

S. John Ross

November 11, 2015 at 8:45 pm

(And illustrated Lore & Legends of Quendor)

S. John Ross

November 11, 2015 at 8:47 pm

You really ARE determined to follow Infocom’s lead, aren’t you? =)

S. John Ross

November 11, 2015 at 8:52 pm

The real name of the scratchboard artist Infocom credited as “Bruce Hutchinson.” He illustrated Lore & Legends of Quendor, and drew the game’s poster-map.

whomever

November 6, 2015 at 9:10 pm

A recent Dr Who Christmas Special had a killer christmas tree that totally made me think of the monsters (probably independently developed though).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGe4JDbAfEk

Matt Wigdahl

November 6, 2015 at 10:39 pm

Count me as another fan of Beyond Zork from back in the misty past. Although I enjoyed several of Infocom’s other titles more than BZ, there was a lot here to like. In particular, the ability to name items was a great feature I lifted for _Aotearoa_.

I thought the combination of CRPG and text adventure just worked for this game, and worked better than I think any previous game had achieved.

I fondly remember many hours of playing this game with friends from high school and trying to finally crack some of the tougher puzzles.

Monty

November 6, 2015 at 10:49 pm

My favorite reference in Beyond Zork is the Christmas Tree Monsters, which call back to the “How to Play” text in the original manual for (at least Starcross, possibly more):

> GIVE THE CATERPILLAR TO THE CHRISTMAS-TREE MONSTER.

THE CHRISTMAS-TREE MONSTER IS REVOLTED AT THE THOUGHT OF ADORNING ITS BRANCHES WITH A CATERPILLAR.

I remember being delighted when the canonical nature of Christmas Tree Monsters hating caterpillars was confirmed.

Rowan Lipkovits

November 7, 2015 at 4:48 am

The deterministic text adventure and the emergent CRPG end up rubbing each other raw almost every time they touch

Really this just makes Quest for Glory look better and better when you consider the delicate job they later did engaging essentially the same undertaking two years later.

Jimmy Maher

November 7, 2015 at 8:04 am

Yes, those are really well-designed games. Looking forward to writing about them, not least because I will get to play them again.

Lisa H.

November 7, 2015 at 9:55 am

to wish that it had made it into more than the single Infocom game that would ultimately feature it

Er, Arthur? Zork Zero? Or are you speaking only of this specific combination of features?

Steve Meretzky, who loved worldbuilding in general, also loved the lore of Zork to a degree not matched even by the series’s original creators.

Can’t blame him, really. Especially with the extra flavor contributed by things like The Lore and Legends of Quendor, it’s really a fun playground, despite its sparseness.

like the platypus, horseshoe, and whistle from Wishbringer

And the Shoppes with their old women and curtains, like the Magick Shoppe?

But still more depressing is the way that Beyond Zork now comes along to muck it up. You play a novice enchanter (where have we heard that before?) who, even as the wise and powerful hero of Spellbreaker sets about destroying magic, is dispatched by the Guild to retrieve the “Coconut of Quendor” that can safeguard it for a return at some point in the future. Why couldn’t Moriarty just leave well enough alone, find some other premise for his game of generic fantasy adventure?

Pendulum swinging back and forth between Science and Magick?

Ethereal Plane Of Atrii, Above Fields

I like the Invisiclues question and first answer for the “vague outline”, which is something like: What on earth do I do with a vague outline? Nothing – on earth.

hippopatamus

Hippopotamus? (unless [sic] in the source, I guess.)

Taking a cue from the roguelike genre, large chunks of Beyond Zork‘s geography are randomly generated anew every time you play

I think it’s not completely random, though, rather that there are a few possible maps the game selects between?

I finally start thinking that maybe it can’t be solved because I didn’t give my character enough dexterity at the very beginning of the game. This can actually happen; Beyond Zork is quite possibly the only text adventure ever written in which you can lock yourself out of victory before you even enter your first command.

Just curious, have you actually encountered this with anything other than the compassion stat?

Moriarty himself left Infocom soon after finishing Beyond Zork, tempted away by Lucasfilm Games […] We’ll be catching up with him again over there in due time.

LOOOOOOOOOOOOOOM*koffkoff* er, don’t mind me…. I’ll see myself out.

Jimmy Maher

November 7, 2015 at 3:42 pm

Yes, the latter.

Thanks. Never could spell that word. We should just call them riverhorses, like so many other languages.

No, I think it’s quite a bit more sophisticated than that. I’ve seen a lot of layouts, and don’t believe I’ve ever seen two exactly alike. The randomization only happens when you first enter one of the varying areas, so if you restore to a point before that you see something new and have to redo your map. In other words, yeah, I saw a *lot* of different maps.

Haven’t tested the other stats exhaustively, no. Might be interesting to see if you can get out of the cellar with no points at all put into dexterity at the beginning of the game…

Lisa H.

November 14, 2015 at 5:42 am

I think it’s not completely random, though, rather that there are a few possible maps the game selects between?

No, I think it’s quite a bit more sophisticated than that. I’ve seen a lot of layouts, and don’t believe I’ve ever seen two exactly alike.

I just poked around with going down into the cellar near the start of the game, and I think you’re right, there’s something more sophisticated going on than just selecting between a handful of preset maps (considering only room connections, and not placement of magical objects). I saved just before going down to the cellar and on 7 entrances, got 6 different maps; one was a vertical mirror image of a previous one. So, I still think not 100% random, but neither is it just selecting from a small pre-set.

Peter Piers

November 7, 2015 at 12:18 pm

I’ll be very happy to catch up with Moriarty later. And I obviously don’t mean Tully Bodine. Loom remains one of the most beautiful games I’ve ever played – though nostalgia surely has a lot to answer for, in light of some stupendous games I’ve played since. Regardless, it made a deep impression on me as a child and I still find its brilliant blend of music, plot and gameplay (as well as the actual choice of music) to be unique.

Pedro Timóteo

November 7, 2015 at 1:23 pm

Great as always. I haven’t played this one yet, but I will (watching out for all those dead ends). :)

I don’t think that Apple II screenshot looks that bad, the map with character graphics looks fine to me. Maybe it’s because I played a lot of Nethack in text mode back in the 90s…

Interestingly, Windows Frotz allows us to choose the system (Amiga, DOS, Mac, etc.) the interpreter tells the game it’s running on, and it’s nice to see the differences (no graphics in some versions, different default colors, etc.). If you choose DEC 20, the game asks whether you have a VT220 terminal or not (with graphics only if you answer yes).

As a curiosity, I believe this is the fourth (and last) Infocom game released for the Commodore 128 but not the C64 (with the others being AMFV, Trinity and Bureaucracy). Infocom was really about the only developer to ever support the C128, unfortunately.

Jimmy Maher

November 7, 2015 at 3:50 pm

The industry’s lack of support for the Commodore 128 is one of those things that I still can’t completely explain. For two or three years it was one of the better-selling platforms on the market, with a user base positively slavering for just about *any* game that ran on the 128 in 128 mode. Yet… (almost) nothing.

In the early days there were several games announced. Sierra planned for a while to bring the AGI games like King’s Quest to the 128, and Telarium announced The Scoop, and I believe there were a number of others. But all fell through. There seems to have been a bit of groupthink going on: “If no one else is bothering with the 128, why should we?” If someone had been brave enough to bring out a reasonably impressive graphical 128-mode game, I think they could have cleaned up. That would likely have prompted others to do the same, and this little corner of computer history could have been very different.

Brian Bagnall

November 12, 2015 at 2:56 am

That is a good mystery why there wasn’t more software and especially games produced for the C128. Wikipedia says there were 5.7 million C128’s sold (it says 4 million elsewhere in the article) vs 5-6 million in the entire Apple II series, yet the size of the Apple II library is way out of proportion. I don’t see references for the C128 sales figures, so possibly the total units is exaggerated. With Infocom pulling out of the C128 market after the 4 games in 1986, this might be as good an indication as any of a weak C128 software market. It also seems likely that Commodore didn’t do very much to promote software development for the C128. I’m going to try to interview an accountant from Commodore who might be able to provide some hard numbers.

Commodore probably thought that it could sell a lot of C128’s due to the pull of a huge C64 library, and then eventually when the installed base of the C128 was large enough, software for the 128 mode would appear. I gotta say, that sounds like a realistic strategy and I’m kind of puzzled why it didn’t happen if the numbers above are even close to accurate.

Jimmy Maher

November 12, 2015 at 8:12 am

I don’t know where there those numbers came from either, but they strike me as absurd. There were shocked reports in the press of 1986 that the 128 was outselling the Amiga by “four to one.” Since the Amiga sold about 100,000 units that year, that would mean that the 128 sold about 400,000 units, which strikes me about right. And that was almost certainly its best year. All indications are that sales all but stopped in the wake of the Amiga 500’s release; the latter made a much better choice for someone looking to spend a little more and step up from a 64. In 1989 the 128 was already cancelled due to lack of interest from buyers. It was a success, but a very brief-lived one.

My own best guess would be, at best, around 1 million 128s sold — and I think even that’s quite a generous estimate. If the 128 really sold 4 million units (much less 5.7 million), it would had to have been handily outselling the 64, which moved a fairly steady 1 million units per year during the mid-1980s and a little beyond. There’s absolutely no indication in the press of the time or anywhere else that that was happening.

The 64’s sales figures were similarly inflated for years, until pagetable.com did an analysis of the serial numbers to arrive at a likely worldwide total of about 12.5 million (http://www.pagetable.com/?p=547). I wish that someone with the skills and connections would do something similar for the 128.

That said, Infocom’s 128 games did do fairly well for them. Brian Moriarty has often mentioned eager 128 buyers as the main reason that his dark, off-putting Trinity *wasn’t* a complete bomb, and they probably contributed considerably to Beyond Zork’s relatively impressive sales numbers for a late-period Infocom game as well — not to mention Bureaucracy, Infocom’s next best-selling game of 1987. I think a graphical game would have done still much better. The Infocom games, after all, were not only all-text but ran only in the 128’s 80-column mode — a mode that many, perhaps most, 128 buyers who hadn’t also bought an RGB monitor couldn’t access. In short, I think there was a huge hunger for a 128 game that publishers never fed. Whether continuing to make 128 games beyond the first that just about every owner would have rushed out to buy would have been worthwhile is, of course, another question…

Markus

November 13, 2015 at 7:24 pm