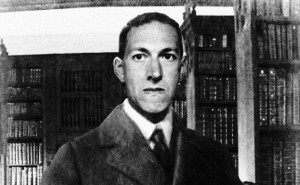

Sandy Petersen first encountered H.P. Lovecraft in the most perfect way imaginable. Poking around his father’s library as a boy in the 1960s, he came upon a battered old paperback called The Dunwich Horror and Other Weird Tales. It was an Armed Forces edition of Lovecraft, one of many hundreds of titles printed cheaply on pulp paper and distributed for free among the soldiers and sailors fighting in World War II. Petersen had no context for the book — no knowledge of the man or his times, no preconceptions whatsoever. There were just the stories. With their strange diction and their sinister air of otherworldliness, they might as well have been dropped into his father’s library from outer space. Petersen felt like one of Lovecraft’s many gentleman-scholar protagonists, encountering a musty old tome that offers a gateway to another world. It was the perfect book at the perfect age, and he was well and truly smitten. Lovecraft remains his favorite author to this day.

It wasn’t as easy to be a Lovecraft fan in those days as it is today. Most of his works were available, if at all, only in editions from the tiny independent publisher Arkham House. Petersen spent years hunting down the stories and learning about the man, treating each new piece of the puzzle as a revelation. And then there came a new obsession: Dungeons and Dragons.

During his first year at Brigham Young University in the mid-1970s, a friend introduced him to the brand new game via a copy of the rules he’d borrowed from one of his professors. Petersen was as immediately smitten with Dungeons and Dragons as he had been with Lovecraft. He soon graduated from player to Dungeon Master, the leader of his little troupe of role-players. With a friend named Steve Marsh, he designed a Dungeons and Dragons variant that Marsh named American Gothic:

By this he meant a fantasy campaign taking place in the modern era, with only a little magic, and most monsters stemming from ’50s horror movies and modern horror literature. I actually started this campaign and went to the trouble of detailing all the possible types of scenarios that could exist, and made up some special rules for combat, experience, and so forth. This campaign was short and abortive, but the things I learned from it planted the seeds for later work.

American Gothic was derailed by Petersen’s group’s love for an all-new RPG that was released in 1978 by a former board-game specialist called Chaosium. It was called RuneQuest.

At a glance, one could easily dismiss RuneQuest as just another me-too fantasy RPG chasing after Dungeons and Dragons players. Look closer, however, and it started to get a whole lot more interesting. RuneQuest games took place in a lovingly detailed world called Glorantha, which Chaosium’s president Greg Stafford had begun slowly elaborating almost a decade before Dungeons and Dragons even existed. Whereas Dungeons and Dragons took place in a vague “lazy medieval” pastiche of Tolkien and popular fantasy, Glorantha was classical in spirit, drawing heavily from Greek and Roman society and mythology. In the spirit of Homer, this was a game where even high-level characters could be killed with a single blow; hit points did not automatically increase when a character gained experience. Like the very first competitor to Dungeons and Dragons, Flying Buffalo’s Tunnels and Trolls, RuneQuest‘s rules fixed many of Dungeons and Dragons other inexplicable aspects, like the way that armor somehow made a character more difficult to hit instead of absorbing damage when she was hit. Most intriguingly of all, it replaced Dungeon and Dragons‘s system of inflexible character classes with a menu of skills from which the player could choose to truly create her own character her own way. And it was all executed intuitively and elegantly, in marked contrast to Dungeons and Dragons‘s mishmash of systems that could make it feel like about five different games stuck together. It was all so new and different that RuneQuest is occasionally still described as the first “second-generation” tabletop RPG. Petersen and company fell in love immediately.

Indeed, Petersen himself, who was now pursuing a graduate degree in zoology at the University of California, Berkeley, without much enthusiasm, was so smitten that he wrote to Stafford personally, asking if he could contribute to the game. A number of magazine articles and a supplement containing new monsters for the game followed. Then came the moment that, in light of Petersen’s twin passions, just had to arrive: he proposed an expansion for RuneQuest that would move the setting from Glorantha to the so-called “Dreamlands” of H.P. Lovecraft, site of a series of lightly interconnected fantasy stories heavily inspired by British fantasy progenitor Lord Dunsany. These tales were and remain far from the most popular of Lovecraft’s stories among fans and casual readers alike, but Petersen thought they’d be perfect for the RuneQuest ruleset.

Chaosium turned him down, delivering the surprising but exciting news that they already had not just a rules supplement but a whole new horror-themed RPG in the works. It would be largely an exercise in Gothic horror taking place in the late nineteenth century, but would nevertheless include the possibility of encountering the Cthulhu Mythos as well. They had already negotiated rights to the stories from Arkham House. (In later years, when it became clear that Arkham’s copyright claim to Lovecraft’s work wasn’t quite as ironclad as they might have wished it was, Chaosium would quietly drop the license whilst continuing to play in the Cthulhu Mythos.) The game was to be designed by an old hand in the RPG community, whose brother had introduced him to the hobby after playing in one of Dave Arneson’s original games of proto-Dungeons and Dragons. But despite its pedigree, Dark Worlds was delivered very late and in what Chaosium judged to be a very unsatisfactory state. With, as Lynn Willis of Chaosium would later describe it, “bad feelings and confusion” all around, the relationship fell apart — whereupon Greg Stafford recalled Sandy Petersen, who was so desperate to be involved in a ludic tribute to his literary hero that he’d offered to do absolutely anything to help, even if that meant just copy-editing or play-testing. Stafford now gave him much more than that to do, tossing the whole project into the lap of one astonished and delighted young zoology student. Zoology soon fell by the wayside entirely as he embarked on the career he continues to this day: that of game designer.

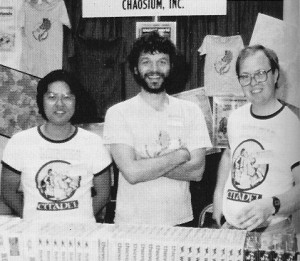

Greg Stafford (center) and Sandy Petersen (right), with Tadashi Ahara, editor of Chaosium’s in-house magazine Different Worlds.

The story of the development of this tabletop RPG of Lovecraftian horror, soon to be renamed Call of Cthulhu, is one of the more fascinating and inspiring case studies in the annals of gaming history. The end result reverberates to this day not only through the world of tabletop gaming but also through its digital parallel. Therefore I’d like to take some time today to look at just what Petersen and his friends at Chaosium did and how they did it.

The great Sid Meier has often advocated starting a game design from its fictional or historical topic rather than beginning with a set ludic genre. His early masterpiece Pirates! provides an excellent example of how productive such an approach can be. Sandy Petersen was considerably more restricted when starting to work on Call of Cthulhu — he needed to deliver something that was recognizably a tabletop RPG at least somewhat in the spirit of Dungeons and Dragons — yet there’s nevertheless much the same spirit of directed innovation about his process and his end result.

If there’s a literary model for the structure of Dungeons and Dragons and its many derivative works, including even Chaosium’s innovative RuneQuest, it must be that most seminal of fantasy novels, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Bilbo Baggins starts off weak and vulnerable, sets off on a series of grand adventures culminating in a showdown with a dragon, and finally returns home a stronger and better little hobbit. In the book he lives happily ever after, while in games he more likely heads off again to do something even more remarkable and get even stronger. Still, the general comparison holds. This is gaming as self-improvement — or, if you like, the ultimate power fantasy. There’s of course a reason that this model held and continues to hold such sway over both tabletop and computerized RPGs: it’s damn fun. Everyone loves the feeling of accomplishment that comes with new hit dice, new spells, new magical equipment. Everyone loves trouncing a monster that just a few levels ago would have trounced you. Yet this mode of play is totally at odds with the spirit of Lovecraft’s fiction. Novice designer that he was, Petersen realized this only slowly, as a project that had first struck him as “relatively easy” for a devotee of the Cthulhu Mythos like himself turned into something that left him “appalled.”

He turned back to Lovecraft’s stories, analyzing how they were put together and how they made him feel as a reader. He then asked how he could create those same feelings in his players. Most importantly, he asked what there was about horror that made it different from high fantasy or giddy adventure, and thus what should distinguish his game of horror from all the RPGs that had come before it.

How can I make the mood of a fantasy role-playing game match the mood of a modern horror story? I needed spooky happenings to get the player chilled, I needed black horrors that would chill the minds and blast the souls of the intrepid investigators, and I needed to make sure that the game did not degenerate into a slugfest or simple matching of power against power.

Lovecraft presents no comforting narratives of self-improvement. His is a deterministic universe where intentions matter little, where even the cleverest and strongest are often doomed by the whims of a malevolent fate. Assuming they survive at all, Lovecraft’s protagonists invariably end up psychologically scarred for life if not actually insane — certainly not eager to count up their newly acquired hit points and set off to do it all again. How to recreate this feeling of near powerlessness within the framework of a game that people would actually want to play? This was Petersen’s challenge.

The core of his response was Call of Cthulhu‘s sanity — or, perhaps better said, insanity — system, a brilliant innovation that is justly still celebrated today for advancing the RPG’s potential as a story-making engine. Like so many brilliant innovations, it wasn’t entirely born of its creator’s own ideas.

Looking through an RPG magazine called The Sorcerer’s Apprentice one day, he came upon an article by Glenn and Philip Rahman that offered the beginning of an attempt to adapt the Cthulhu Mythos to Tunnels and Trolls. It outlined a “willpower” statistic. If a character saw something particularly horrifying, she would have to make a willpower check to avoid running away in terror. Fail badly enough and her willpower score would be permanently reduced. The article came and went in the world of Tunnels and Trolls without making much impression. But when Petersen read it it hit him with the force of a revelation. Call of Cthulhu characters could have a “sanity” statistic that would be difficult or impossible to increase but all too easy to decrease. Knowledge of the Mythos, in many ways the very object of the game, would, almost paradoxically, have the important side effect of costing a character sanity. Once a character went insane, she would revert to the control of the “Keeper,” Call of Cthulhu‘s equivalent of Dungeons and Dragons‘s Dungeon Master, quite possibly to suddenly make life much more difficult thereafter for the rest of the players. Meanwhile the player whose character had just gone insane would have no option other than to roll up another. If nothing else, the system would ensure that the lifespan — sanity-span? — of most characters in Call of Cthulhu who persisted in their investigations would be quite short. Thus weak, inexperienced characters would remain the norm. If your Call of Cthulhu characters manage to improve more than once or twice before insanity or death get them, you’re quite probably playing it wrong. Call of Cthulhu is lethal by design.

When Petersen first tried the system on real players, he himself was shocked at how effective it proved to be in evoking the spirit of Lovecraft.

My players found a book which enabled them to summon up a Foul Thing From Otherwhere (a dimensional shambler) and decided to do so. At the moment they completed the spell, the players suddenly chimed in with comments like “I’m covering my eyes.” “Turning my back.” “Shielding my view so I don’t see the monster.” I had never seen this kind of activity in an RPG before – trying NOT to see the monster? What a concept. You may not credit it, but I had actually not realized that the Sanity stat, as I had written it, would lead to such behavior. To me it was serendipitous; emergent play. But I loved it. The players were actually acting like Lovecraft heroes instead of the mighty-thewed barbarian lunks of D&D.

The deadliness extends well beyond the sanity system that stands as the game’s most central innovation. Chaosium had extracted the core mechanics from RuneQuest to create their “Basic Role-Playing” engine, a house system meant to power all of their future games, including Call of Cthulhu. Thus Petersen’s new game already came equipped with an unusually gritty and lethal combat system. “Investigators are not fighting machines,” he wrote in the rules. He further made sure that all of the various Mythos gods and creatures would be suitably overpowered in comparison to the players’ characters. As he’s often noted since in interviews, the least dangerous opponent you’re likely to encounter in the game is a cultist, who’s pretty much just like you. Thus the best you can hope for is even odds, and as far as going toe to toe with the likes of Cthulhu himself… forget about it. There’s an old axiom among Call of Cthulhu players that if a scenario ever comes down to gunplay you’ve probably already lost. It’s the first RPG in history whose combat rules are used as often as not when the players are just trying to get the hell away from something, not to kill it. In making the characters so fragile, so human, Call of Cthulhu can prompt a connection between players and characters that other games can never hope to achieve. Death, injury, and insanity mean something in this game.

Petersen replaced combat as the main focus of Call of Cthulhu with investigation, even going so far as to officially name the players’ characters not “adventurers” but rather “investigators.” This shift was thanks to a quality in Lovecraft’s stories, seemingly so resistant to becoming conventionally fun games, that actually makes them unusually suitable for ludic adaptation in comparison to most works of horror. At heart, many of Lovecraft’s stories are mysteries. The story “The Call of Cthulhu,” Petersen’s game’s namesake for a very good reason, is a perfect example. Its protagonist is an academic who, after coming upon some curious documents among his recently deceased grand-uncle’s papers, slowly ferrets out layer after sinister layer of a global conspiracy of evil. The classic mystery structure is, as I’ve described in a previous article, a perfect setup for a ludic narrative. The real story in a mystery is fixed, leaving the game designer only to provide for the more manageable, almost purely logistical scenario of its uncovering, whilst leaving the player with an obvious goal: to learn more, to solve the puzzle that is the mystery. For this reason mystery stories and games were often intertwined well before the arrival of Dungeons and Dragons or computerized adventure games: R.A. Knox’s ten rules of good practice for designing a mystery; the Baffle Book of solve-em-yourself mystery stories by Lassiter Wren and Randle McKay; the classic board game Cluedo; the Crime Dossiers of Dennis Wheatley and J.D. Links, proto-RPGs that captivated players four decades before Dungeons and Dragons. In a sense Call of Cthulhu would merely continue an already long tradition.

As the first full-fledged RPG to do so, however, it was also unique. With combat so lethal and as often as not pointless, other skills came to the fore. Call of Cthulhu became the first and quite possibly still the only RPG where “Library Use” is one of the most valuable skills one can have. Many other skills are equally cerebral: “Accounting,” “Archaeology,” “Law,” “Linguistics,” “Geology,” “Zoology”; the list goes on and on. Playing Call of Cthulhu is a nuanced, intellectual exercise in comparison to its antecedents, a process of ferreting out information and piecing together clues that forces a real engagement with the story and the setting that most games of Dungeons and Dragons lack. Given the nature of the Mythos, it would be quite the stretch to call Call of Cthulhu “non-violent.” Yet it was certainly a different and in its way a more realistic take on violence than had been seen in RPGs before. Violence here is horrifying, as it should be. It’s also swift and deadly and deeply damaging to characters’ psyches as well as their bodies, just as it is in reality. Call of Cthulhu feels like a game for grown-ups, a game capable of producing real drama. Petersen himself notes that “no one’s impressed when a Dungeons and Dragons party kills a werewolf, but when you face off against such a fearsome beast in Call of Cthulhu and survive, it’s a tale worth retelling.” An official Chaosium description of the game further emphasizes just how markedly it departed from all that had come before:

There are no material rewards for those who choose to risk their lives and minds discovering the eldritch horrors hidden in the darkest corners of the world. There are no caches of treasure that await discovery by fearless and intrepid explorers, nor does fame and glory come to those who should defeat some being from “outside.” Those individuals who would speak publicly of what they have learned will soon find themselves ridiculed or even worse. Exploring the Cthulhu Mythos is a more or less solitary pursuit, small groups of adventurers only rarely coming into contact with others who may have some knowledge of the Mythos’s secrets. Even these individuals are usually unwilling to speak too freely of what they know and some, having lost their minds, may prove to be actual worshippers of the hideous Other Gods or Great Old Ones. Those who would choose to learn too much about the Mythos are driven mad, anyone gaining near complete knowledge losing all of his sanity permanently. The only motivation to continue the exploration of these mysteries is that of human curiosity; a desire to know the truth, regardless of the cost. This motivation is common to both the players of the game and the protagonists of the stories.

As Petersen tells the story today, Greg Stafford, Lynn Willis, and the other principals at Chaosium had “contempt” for Lovecraft as a writer, considered him a “hack.” An idealistic take on this might be to say that they were, like many others — myself included — more intrigued by the idea of the Mythos and its potential than thrilled with its actual execution under Lovecraft’s hands. But even that may be too generous a spin. Petersen claims that, eager to find a competitive edge in the increasingly crowded field of RPGs, Chaosium’s strategy at the time was simply to make games in as many viable preexisting literary worlds as possible. During the first half of the 1980s, the strategy also yielded a game called Stormbringer that took place in the world of Michael Moorcock’s fantasy hero Elric, one playing in Larry Niven’s Known Space setting, and another based on the ElfQuest line of comics. There was also a supplement that let players of many fantasy games adventure in Robert Asprin’s much-loved Thieves’ World milieu, and one that would have similarly opened up the world of Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories had TSR not wrested the license away at the last minute. None of these efforts represent quite as radical a re-imagining of the RPG as Call of Cthulhu, but all did contribute in their own way to bringing more sophistication and storytelling nuance to the form.

In the case of Call of Cthulhu, the folks at Chaosium found a task that they could approach with almost as much passion as Petersen did the core rules. Lynn Willis in particular put a great deal of time and energy into “A Sourcebook for the 1920s,” an entirely separate book included along with the core rules in the box. It’s an interesting document even for those with no real interest in playing the game to which it’s attached, including along with maps of the world as it then existed treatises on crime and law enforcement, on (non-fictional) cult activities, on travel by air and rail and sea (complete with typical timetables), on money and prices, on important historical personages. Chaosium had largely originated the idea of the elaborate RPG sourcebook with RuneQuest‘s world of Glorantha, but the one included with Call of Cthulhu, built as it is from the real world, feels qualitatively different. Petersen has since been dismissive of Chaosium’s efforts to ground the game so thoroughly in Lovecraft’s own times, saying that what is important is the horror, not the setting.

The Chaosium folks wanted to enjoy playing the game I was going to design, and they wanted a “hook” to hang their fun onto. They chose the 1920s. In their games, they loved driving old cars, talking about zeppelins, flappers, the Weimar Republic and all that stuff. My own games usually didn’t reference the era at all, except peripherally. Yeah, they were in the 1920s too, but they could just as easily have been set anywhere in the 20th century. A haunted house is a haunted house as far as I was concerned.

If he’d had his druthers he’d have placed the game in the (then) present day of circa 1980. This, he says, would “let the keeper take more for granted about the world and not get caught up in details such as ‘Were there trans-Atlantic flights in the early 1920s?'” Personally, though, I think the game benefits enormously from the efforts of Willis and company. The setting is for me a huge part of the game’s murky personality — but then, I’m the sort who gets genuinely curious whether there in fact were trans-Atlantic flights in the early 1920s. (The answer, for the record, is that there weren’t, unless you were Charles Lindbergh. Late in the decade you could book passage on a zeppelin, if you had the means.)

While the gist of the rules themselves would remain very true to Petersen’s original design, Chaosium did tinker here and there in the interest of playability. Most notably, they dialed back Petersen’s brutal sanity/insanity system just slightly by making it possible in some circumstances to regain lost sanity points, and by introducing the idea that some forms of insanity might be only temporary. It was a fine line to walk, remaining true to the spirit of Lovecraftian horror while not creating a game that just felt too futile, pointless to even bother playing. Despite his fearsome reputation, Lovecraft did occasionally allow his protagonists small victories. For instance, the labyrinthian hell beneath New York in “The Horror at Red Hook” is sealed off with concrete at the end of the story, although it’s strongly implied that this represents at best a stopgap. Similarly, “The Colour Out of Space” returns whence it came in the end — even if, ominously, it also seems to leave a small part of itself behind. Chaosium’s tweaks let Call of Cthulhu capture the feel of these small victories, a feel not so much of triumph as of having briefly delayed the inevitable, having kept the cosmic evil at bay for a few more months or years. Petersen, to this day a notoriously lethal Keeper, predictably thought that Chaosium’s tweaks went too far. Once again I disagree; I think they add just enough hope to make each new battle against the Mythos feel worthwhile. Lynn Willis:

Dark endings may be effective ways to end short stories, but they do not work for fantasy role-playing — nobody enjoys seeing their characters always crushed, impaled, drained, sliced, throttled, and otherwise made corpses without relief, and neither is it much fun to have investigators staggering from catatonia to amnesia to stupefaction without much chance to do more than shrug.

That said, the game remains insanely (ha!) deadly in comparison to most of its competition, and Call of Cthulhu thus remains a tough sell for many players. Many simply loathe the bleakness of its premise. Others point to what they see as a fundamental design flaw: the fact that the insanity system directly motivates players not to want to follow through on the ostensible goal of the game, that of learning more about the Mythos so as to better combat it. It’s hard to really argue against the truth of this statement. The question must be whether the narrative texture provided by these two competing motivations is more important than Call of Cthulhu‘s merits (or lack thereof) as a piece of traditional, fair game design. Even among fans, Call of Cthulhu seems to work best in fairly small servings. Certainly long-running campaigns of the sort that are common to Dungeons and Dragons are quite rare in the world of the Mythos. In some ways almost as much an artistic experiment as an attempt to create a likable, playable game, Call of Cthulhu‘s very structure has always limited its appeal.

Released in late 1981 with relatively little fanfare, Call of Cthulhu proved to be a steady seller if never quite a spectacular one. Chaosium supported the game lavishly, particularly for the first several years after its release, which marked a very good period commercially for the company in general. Some of the scenarios and supplements they released have become almost as iconic as the game itself. Benefiting from the fortuitous release of the hugely popular movie Raiders of the Lost Ark just a few months before Call of Cthulhu, much of this material leaned rather heavily on pulpy globe-trotting adventure at the expense of the horror, a development that Petersen always to a greater or lesser degree decried. Yet it’s also hard to argue with some of the results, especially given the element of campy fun that’s always been such a big part of Lovecraft’s own appeal as a writer. Perhaps most legendary of all the Call of Cthulhu supplements is something called Masks of Nyarlathotep by Larry DiTillio, a scenario so huge it needed to come in a box all its own to hold its 450 pages or so worth of detail along with all of its maps and other goodies. No one else in tabletop or digital games at the time was implementing scenarios of this scope and complexity. Sure, it felt at least as much like Indiana Jones as Lovecraftian horror, but, what with opportunities to travel around the world battling cultists in lovingly evoked 1920s versions of New York, London, Egypt, Kenya, and Shanghai, who could really complain? (Well, Petersen to some extent could…) Compare this with the typical Dungeons and Dragons adventure module of the day, which consisted of 20 to 30 pages mapping out the bare tactical challenges of a dungeon and its inhabitants, with all of a paragraph or two giving the players a reason to explore it. Many players found the grand international tapestry of adventure woven by Masks of Nyarlathotep and scenarios like it more compelling than the Cthulhu Mythos itself, resulting in a whole new sub-genre of RPGs focusing on pulpy inter-war adventures rather than horror.

After spending some years with Chaosium in the 1980s, working on Call of Cthulhu and other games, Sandy Petersen migrated to the digital realm, a move he frankly acknowledges to have been precipitated by the hard fact that there’s a hell of a lot more money in computer than tabletop games. We’ll likely be meeting him again in future articles in his new role as a designer of computer games. Chaosium, however, stayed the course and stuck to the tabletop, a decision that brought more downs than ups after the company peaked in influence and commercial success sometime shortly after 1984, the year of Masks of Nyarlathotep. Despite nearly going under on multiple occasions, Chaosium has straggled on right to the present day, sometimes as a “real” business with a few full-time employees, sometimes as little more than a hobby. Call of Cthulhu is the only game they’ve maintained continuously in print throughout that period, often as the only game in their catalog. Its influence and reputation have always outstripped its actual sales, but it remains a classic example of game design, eminently worthy of study by designers writing for the computer as well as the tabletop. In the latter realm, some more recent systems like Trail of Cthulhu by Pelgrane Press have attempted to create a more playable, forgiving version of a Lovecraftian RPG, while other systems, like the long-lived The Arkham Horror, have tried to do the same as board games. (Not having played any of these games, I can’t speak to their success.)

But, this site being The Digital Antiquarian rather than The Tabletop Antiquarian, I’d like to conclude this article not with an exhaustive history of the later years of Chaosium or Call of Cthulhu or its many paper-and-cardboard heirs, but rather with the real point of this side trip to the tabletop: the immense and too-often overlooked shadow that that original tabletop Call of Cthulhu casts over so much computer-gaming history that follows it. Many computer games, beginning with Infocom’s The Lurking Horror (subject of my next article), were inspired to a greater or lesser degree by Call of Cthulhu‘s example to also play with the Mythos. Some adopted a great deal of their tabletop progenitor’s structural underpinnings. The Hound of Shadow, for instance, developed by the appropriately named Eldritch Games and released in 1989 by Electronic Arts, is practically an unlicensed computerized version of Petersen’s design, complete with a set of suspiciously similar skills to choose from.

Yet almost more interesting, and probably even more important, is the role that Call of Cthulhu played as a proof of concept showing that it could be just as captivating to play someone weak and alone and afraid as an almighty world-conquering hero. Alone in the Dark, the urtext to a whole new gaming genre that became known as survival horror, put that premise to good use in 1992. Just to further underline the association, it also plays with the Mythos, being loaded with references to Lovecraft’s works and lore. Other perennial survival-horror series, like Resident Evil and Silent Hill, later built on Alone in the Dark and by extension on the original Call of Cthulhu, often losing the explicit Lovecraftian references but retaining always the delicious horror of being all alone and very nearly powerless in a cold, unforgiving world. Suffice to say that this is a thread that we’ll be coming back to from time to time just as long as I continue to write these articles for you. Credit where it’s due, then, to Sandy Petersen and Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu. Games just don’t get much more influential than this one.

(Sources: the book Designers and Dragons Volume 1: The 1970s by Shannon Appelcline; Different Worlds of February 1982, July/August 1985, and January/February 1986; interviews with Sandy Petersen by Matt Barton, The Gentleman Gamer, Yog-Sothoth, and The Escapist; Petersen’s own “review” of his game on RPG Geek; Grognardia’s post on “The Prehistory of Call of Chtulhu“; Places to Go, People to Be’s history of RPGs. Plus my own memories, alas from long ago now, of battling eldritch horrors with my friends. Thanks, Sandy!)