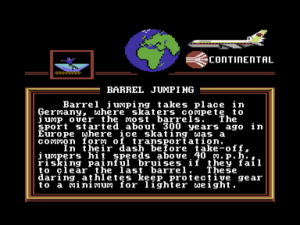

In a hole in a mound there lived an orc. Not a clear, dry, sandy hole with only spiders to catch and eat, nor yet a comfortable hobbit hole. It was an orc hole, and that means a dirty, clammy, wet hole filled with bits of worms and a putrid smell.

It had a perfectly round garbage heap, blocking the doorway, with a slimy yellow blob in the exact middle for spitting practice. The doorway opened onto a sewer-shaped hall — a deeply unpleasant tunnel filled with smoke, with secret panels, and floors snared and pitted, provided with treacherous chairs and lots and lots of booby traps — the orc was fond of visitors.

But what is an orc? Orcs are not seen much nowadays, since they are shy of human beings. They are a pungent people, little bigger than overweight elves, with the charisma of blow flies and the appetite of gannets. Orcs have little or no magic, except a rudimentary skill with knives and strangling cords and, in short, they are evil little pits.

This orc was unusually ugly, even for an orc. His name was Grindleguts.

Grindleguts had lived in the neighborhood of The Mountain for about a year and most people considered him two steps lower than a tapeworm, not only because of the smell and the plague, but because he kept eating their household pets.

— Knight Orc

Level 9 signs with Rainbird. From left: Nick Austin, Tony Rainbird, Paula Byrne, Pete and Mike Austin.

The Austin family who ran Level 9, suddenly Britain’s other great adventure house, would have had to have been almost incomprehensibly magnanimous not to have resented just a little bit Magnetic Scrolls’s breathtaking ascent to prominence on the back of The Pawn. By the time they too signed with Rainbird in 1986 Level 9 had been selling adventure games for four years, amassing a stellar reputation for their ability to pack a staggering amount of text and gameplay into the likes of a little 48 K cassette-based Spectrum. Their games had their problems in terms of puzzles that really needed more thought or at least more hints, but that was such par for the course at the time that British gamers barely seemed to notice whilst marveling over their expansive worlds and the pictures the Austins were soon managing to shoehorn in on top of everything else.

What the Austins couldn’t seem to manage, however, was that single breakout hit that would separate itself from their catalog. This wasn’t hugely surprising in itself; the British adventure market was largely a niche market. Only once every year or two did an adventure like The Hobbit or Sherlock become a force to be reckoned with outside of the magazines’ specialized “Adventure” chart listings. Level 9’s best-selling single game to date had been their least typical. Published by Mosaic rather than Level 9 themselves at the height of the British bookware boom, The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 was essentially a Choose Your Own Adventure version of Sue Townsend’s comic epistolary novel of the same name, which was a popular literary sensation in Britain at the time. The ludic version consisted of episodes lifted directly from the novel glued together with unsightly globs of Pete Austin text trying rather too hard to recreate the voice of Townsend’s fussy hypochondriac of a teenage boy. No matter — the license alone was strong enough to push sales well past 150,000 and prompt a second, somewhat less successful game based on the next book in the burgeoning series.

When Level 9 opted to forgo publishing their own parser-driven adventures and signed a contract with Rainbird in early 1986, it was with some hope that the latter could foster the big hit that had so far eluded them and make a name for them in the fabled land of milk and honey known as North America, where money rained from the sky and punters picked it up and plunked it down to buy computer games costing $40 or more. Tony Rainbird’s right-hand woman Paula Byrne whilst working for Melbourne House had brokered the deal that had brought The Hobbit to North America in a deluxe package under the Addison-Wesley imprint, where it had done almost as well as it had in Britain. Thus the Austins could feel reasonably hopeful that she might be able to do something similar for their next game. How disappointing, then, when Rainbird’s big transatlantic hit of an adventure game turned out to be one from a company no one had ever heard of before the launch. To be fair, it was awfully hard for Level 9’s crude vector graphics to compete with the beautiful hand-drawn pictures in The Pawn, and equally hard for the three boffinish Austin brothers to win any attention from the mostly young male trade press when the alluring Anita Sinclair was available for questions somewhere else on the same show floor.

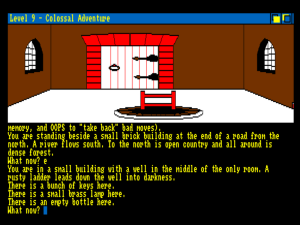

Jewels of Darkness on the Amiga. The graphics didn’t compare too favorably to those of The Pawn.

It also didn’t help that Level 9’s first game for Rainbird was a retread. Jewels of Darkness packaged together their first three games, their so-called “Middle Earth” trilogy, with the Tolkien fan-fiction serial numbers filed away; it was actually something of a small miracle that Level 9 hadn’t been sued by the Tolkien estate already. Level 9 added vector graphics to the text-only originals and, this being a Rainbird game, a novella to set the scene. While it was politely received by reviewers in Britain, sales were doubtless impacted by the fact that many of the hardcore adventurers most likely to buy the somewhat pricy collection already owned one or more of these games in the original. In North America, where Jewels of Darkness became the first ever Level 9 game to be sold, the reception was less polite. Without the historical context or the requisite warm haze of nostalgia in which to view these fairly primitive games, reviewers were left to nitpick the collection’s shortcomings and dwell on the fact that the first game of the trilogy, Colossal Adventure, was essentially an uncredited ripoff of the original Adventure. It was by no means the first version of Adventure to be sold without permission from or reparation to Crowther and Woods, mind you, but its being sold at this late date and under another name fueled a belated sense of outrage on the part of many. When not accusing the Austins of plagiarism, reviewers just talked about how bad the pictures were in comparison to those in The Pawn.

Level 9’s second game for Rainbird, Silicon Dreams, was another collection, this time of their “Eden” trilogy of science-fiction titles that had begun with Snowball, still perhaps their most innovative and interesting game to date. But few took the time to notice the charms of Snowball or either of the other included games. Without controversy to win it even a modicum of attention, Silicon Dreams just vanished.

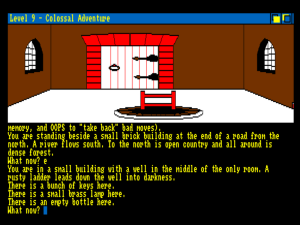

The underwhelming performance of the two trilogies is understandable, but I’d be doing Level 9 a disservice to join so many contemporary reviewers and gamers in dismissing them completely. As primitive as the games themselves are, you see, the interpreters in which they run on the bigger, newer machines like the Atari ST and Amiga are anything but. Level 9 took advantage of the acres and acres of unused memory available to them on those platforms to implement a number of conveniences that go beyond even what Magnetic Scrolls was doing at the same time. Rather than constantly blocking your machine, pictures load and draw as background tasks whilst you continue to interact at the command line, even on machines that don’t normally support multitasking. You can save a game quickly in memory instead of on disk to come back to it later by using the “ramsave” and “ramload” commands. You can scroll backward and forward through your command history using the arrow keys. And, most impressive of all, you can undo up to about a dozen turns by simply typing “oops.” When you enjoy these sorts of features on a modern interactive-fiction interpreter, you’re enjoying ideas pioneered by Level 9. To take the time to credit Level 9 for them here can feel a bit like celebrating the guy who devised a new bolt to hold your car together, but these sorts of innovations are important in their own right in making text adventures more enjoyable and accessible. So, credit where it’s due. These are conveniences the like of which Infocom and Magnetic Scrolls would never implement to anything like the same degree; neither, for instance, would ever offer more than single-level undo, and even that would be long in coming.

Indeed, Magnetic Scrolls, sexy pictures or no, can feel like quite the hidebound traditionalists in relationship to the late works of Level 9. Nowhere is the difference starker than when we get to Level 9’s third game for Rainbird, an original work at last. Boy, was it original. While Magnetic Scrolls was polishing up a more perfect Zork in the form of Guild of Thieves, Level 9 was seemingly trying to blow up just about every assumption ever held about the genre with Knight Orc.

Released in July of 1987, Knight Orc is a glorious hot mess of a game that introduced Level 9’s newest adventure engine: KAOS, the Knight Orc Adventure System. No, the acronym doesn’t quite match the name, but I think we can forgive them a bit of fudging because never has an acronym better fit to a game’s personality. Rather than the static worlds that were still the norm in adventure games, KAOS worlds were to be filled with active characters — potentially dozens of them — moving about following agendas of their own. Each is effectively your equal, able to do anything you can instruct your own avatar to do. In fact, learning to use these characters as alternatives to the character you directly control is key. Once you bring a character under your sway, whether through bribery or coercion or plain old kindness, you can issue commands to that character through the mouth of your own, get that character to do just about anything your own can do — and sometimes a bit more, if she has abilities your own does not. You can issue long strings of commands to your minions that might take ten turns or more to carry out. The more complex problems you encounter can require using this capability to orchestrate the actions of several non-player characters working in carefully plotted concert with your own.

Level 9 also announced that beginning with Knight Orc they were just so over mapping, quite a reversal indeed from this company that had previously felt obligated to put at least 200 locations into each of their games. KAOS games would still consist of a grid of discrete rooms, but the right-thinking player would use a handy in-game map or list of notable landmarks to get around by using “go to” in lieu of tedious compass directions.

It all added up to the most radical single reimagining of the text adventure of the genre’s commercial era. Infocom had played with more dynamic, responsive storyworlds of their own, particularly in their first trilogy of mystery games, but never on a scale like this. Perhaps the only games that really compare are Melbourne House’s The Hobbit and Sherlock, which offer much the same Looney Tunes, even-the-programmer-has-lost-control-of-this-thing experience as Knight Orc. Pete Austin actually called Knight Orc Level 9’s “Hobbit basher” before its release. Yet, impossibly, Knight Orc is even stranger. Not even The Hobbit let you orchestrate the activities of multiple minions, like a strategist sitting at the center of a web of action and reaction. What the hell was Level 9 thinking?

Well, whatever they were thinking, it was something of a thoroughgoing theme by this period in their history. The Austins had spent much of their time during 1985 and 1986 on a quixotic project to create a multiplayer text adventure similar to but much more advanced than Richard Bartle’s M.U.D. This was a fairly logical leap to make from single-player text adventures, one Level 9 was hardly alone in contemplating; Infocom, for instance, also spent considerable energy on a proposed online version of their interactive fiction during their salad days. Level 9’s plans, however, were unusually grandiose by anyone’s standards. Avalon was to be based on the Arthurian legends, and was to play in a virtual world consisting of 10,000 locations and 1000 non-player characters — all the standard cast like Arthur, Merlin, and Morgana included — in addition to the many real humans who would also be logged in and wandering about. It would offer an “incredible number of puzzles” for them to solve in traditional text-adventure fashion in the beginning, but Level 9 anticipated that as a player grew in wealth and power her experience would gradually transform, as in some high-level Dungeons and Dragons campaigns, into one of strategy, politics, and resource management. The whole thing would run on a network of souped-up Amigas and/or Atari STs attached to banks of modems.

It was all hopeless, of course. Level 9, still a tiny family company, didn’t have anything like the resources to pull it off, even assuming they could answer the million practical questions raised by even the quick summary I’ve just given. (What happens when all those puzzles have been solved by eager players? What happens to this Arthurian mythos when some enterprising player kills Arthur? Etc., etc.) Avalon was quietly abandoned by the end of 1986.

KAOS was not, as one might initially suspect, a single-player consolation prize that went into development after Level 9 realized that Avalon just wasn’t going to work. The two projects were actually in development in parallel for some time. Indeed, both were manifestations of deeper predilections that had been with Level 9 for a very long time now. Their very first attempt at an adventure game, written in BASIC for the Nascom kit computer well before Colossal Adventure, had been called simply Fantasy. The game itself seems to have been lost to time, but its description reads like a dry run for Knight Orc. Pete Austin:

It was a game with about thirty locations. It had people wandering about and essentially it was one of the few games where the other characters were exactly the same as the player and they were all after the gold as well. What made it amusing was that they had quite interesting characters, each had a table of attributes, some of them were cowardly, some of them were strong — that kind of thing and we gave them names. There was one called Ronald Reagan and one called Maggie Thatcher and so on, so you could wipe out your least favourite person!

This desire to find a way to let you share your adventure with others, whether in the form of dynamic non-player characters or other flesh-and-blood humans, had obviously never left Level 9.

Level 9’s seemingly sudden abandonment of mapping and traditional navigation was similarly not quite so sudden as it appeared. As early as Snowball with its 7000 rooms set inside a vast generation ship in interstellar space, they had begun to show an interest in more organic, realistic storyworlds where success didn’t depend on methodically visiting every location and plotting it all on paper but rather going where the situation — the plot — led.

And what a plot and situation Knight Orc had to offer! If the quote that opened this article makes you laugh half as much as it does me, you’re on this game’s wavelength. Now consider this: you play the benighted orc Grindleguts. Much of the credit for the… um, unique atmosphere of Knight Orc must go to one Peter McBride, a talented writer who sparked up a friendship and, soon, a working relationship with Pete Austin circa 1984 that would turn him into the most significant single contributor to Level 9’s games without the last name of Austin. A computer hobbyist and self-taught programmer in his own right, McBride already had quite some experience combining computers and writing before meeting the other Pete, authoring books and many a simple BASIC program for the Spectrum. His first major job for Level 9 was to write the novellas, almost 50 pages each, that accompanied Jewels of Darkness and Silicon Dreams. After that he wrote the novella for Knight Orc, of which the introduction above is just the beginning. It’s been described by Robb Sherwin as “the finest piece of authorized fiction ever to accompany a game,” and offhand I certainly can’t think of a better to use in disagreement. Just as importantly, McBride played a big role in crafting the game itself, writing or rewriting much of its text.

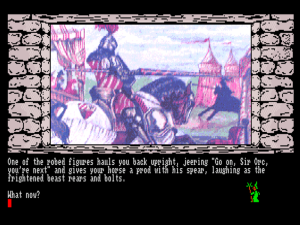

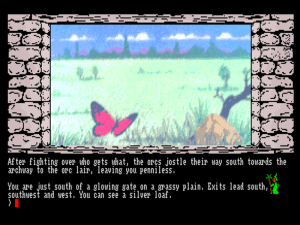

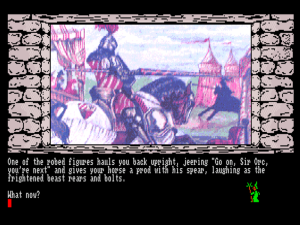

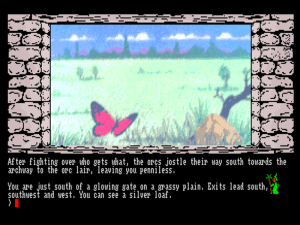

Knight Orc on the Amiga.

Where to start with the walking, talking collection of lowest common denominators who inhabit Knight Orc, all squabbling after the treasures lying about the place and inflicting their petty little cruelties on poor little… well, okay, Grindleguts is equally loathsome. Maybe with the jousting horse who looks like “a flatulent barrel.” Or with the fighter who looks like “a butcher’s shop on two legs.” Or the ant-warrior Kris who looks like “an ogre-sized fried roach.” Or the town layabout, “a lanky, twitchy-fingered nicotine addict.” The most cutting statement of real-world politics comes with the village priest:

He is a sweaty paedophile, quite happy to swarm on about the meek inheriting the Earth, turning the other cheek and the love of you know who... until you mention liberation theology, disarmament, or anyone other than male humans becoming ministers.

And then there’s the knight. God, I love the knight in all his sub-Chaucerian splendor.

>examine knight

"A handsome, parfait knight, great-muscled, fit and slim.

Almost a giant in height, and long and straight of limb.

Clad all in green is he, and green his skin and hair.

His eyebrows are mossy, bright emerald his stare.

No shield, helm or plastron, nor bright chain mail has he.

Of armour has he none. Just, in one hand, holly.

Storm-like and strong, he seems. And swift to strike and stun.

Dreadful his blows, one deems. Once dealt, true death has come."

In other words, he is a bully of the worst type.

The green knight puffs himself up and stares down scornfully from the back of his overgrown pony.

"If thee be brave, not coward base,

Then thee must now my challenge face.

With this, my axe, strike blow for blow.

I'll let thee strike first. Have a go!"

He indicates his mighty axe.

>hit horse with axe

With a surprisingly dextrous stroke you behead the horse. The green knight shouts in surprise, but, before he can retaliate, the massive steed has fallen on him!

That’s such a delicious scene, pretty much exactly what I want to see someone do every time the battle improbably stops around Aragorn in the Lord of the Rings movies so he can make another speech about Courage and Honor. Cheaters always win and karma doesn’t exist in Knight Orc. This combined with the focus on dynamic characters makes the game an experience all its own. There are some set-piece puzzles that could have been dropped into almost any adventure game, but they’re in the minority. The majority of the problems you face must be solved by interacting with the others — often, as in the case above, treacherously and to their considerable detriment.

When you die you’re taken to Orc Heaven, revived, and spit back out into the game. The same goes for all of the various other characters, whether killed by you or by each other. This only adds to the Bizarro World personality of the game. If Level 9 had imagined that their active characters would make the game more realistic, would advance them toward that ultimate dream of making the player feel she had (to paraphrase Infocom) “woke up inside a story,” their efforts can only be judged a failure. For one thing, you can’t really talk to any of your minions at all beyond saying “hello”; you can only order them about, using them like automatons at your beck and call. Level 9 themselves would come to talk about their “characters on rails,” a phrase which gives a pretty good sense of the experience of playing Knight Orc. I don’t really say this to criticize, merely to try to describe just what a deeply weird experience it is.

Knight Orc is really, really funny, but it’s also really, really broken. Let me give an example, involving the most low-rent possible version of an English gentleman hunter. Every time you come to a certain crossroads, he bursts out of hiding to harass you:

A mounted hunter bursts through the trees and spurs his nag towards you. Repeated shouts of "Yoiks! Tally ho!", together with his choice of red as camouflage, demonstrate his hunting skill. The fool is waving his lasso and clinging on for dear life.

Not surprisingly, the hunter gets hopelessly entangled in his lasso and misses you completely. Unfortunately, his horse has better luck when it lashes out with one huge hoof.

Woops! That hoof sends you to Orc Heaven.

My eventual solution to this dilemma was to get the hunter to kill someone called Denzyl in my stead, “a right gullible and stupid-looking person” who’s just gullible enough to take me as his friend.

>denzyl, kill hunter

Denzyl says, "No sooner said than done."

The hunter strikes out wildly with his whip. As is traditional when orcs or their allies are attacked by humans, his blow is deadly. Odin enters from the southwest. Not surprisingly, the hunter gets hopelessly tangled in his lasso and misses you completely. Unfortunately, his horse has better luck when it lashes out with its huge hoof.

In spite of that last sentence which would seem to imply the contrary, I’m still alive at this point, standing there with a suddenly passive hunter and his horse who’s now willing to trade me his lasso — the real point of this whole exercise — for a bit of treasure. Problem solved, right? Well, yes, except that this whole solution was dependent on some combination of emergent behavior and simple bugginess; as best I can tell, the game seems to have been confused by the fortuitous arrival of Odin (don’t ask!) just as the hunter’s horse was about to kill me. The “official” solution to this puzzle is to tie a rope to some signposts, thereby tripping the hunter’s horse and sending him sprawling along with his lasso. I like to think that this little example illustrates everything that’s so good and so infuriating about Knight Orc. I got lucky this time in that “solving” the puzzle in this way didn’t break anything elsewhere. Break one of the middle links in a longer chain of causality in such a way, though, and you might not be so lucky, leaving the game in an unwinnable state that will be all but impossible to track down and correct. Building a dynamic, simulation-oriented game in lieu of just a set of set-piece puzzles is a tremendously demanding endeavor in that everything in that world — even things the programmer has never anticipated — has to work right. Knight Orc too often fails that test. It’s a complicated, difficult game that you can’t trust as a player — a fatal situation.

Unlike Magnetic Scrolls, who chose to demand a disk drive on the 8-bit machines and thus had recourse to virtual memory, Level 9 chose or felt compelled to continue to support the little 48 K cassette-based machines on which they’d built their reputation. Thus Knight Orc is artfully split into three smaller games that each load into memory separately. The first of these revolves around making a long rope to get Grindleguts back into the orc stronghold outside of which he’s been trapped by a long string of very amusing happenstance detailed in McBride’s accompanying novella. He does this by tying together every vaguely ropelike thing he can find, including the aforementioned lasso and even Goldilocks’s hair, which, in one of the most amusing bits of the game, he rudely hacks off like the sniveling little reprobate he is. This first part of the game is fairly manageable, one dodgy puzzle involving a thorny hedge and a welcome mat aside. Once you get to the stronghold, however, the complexity ramps up dramatically. Amongst other things, you need to collect and use no fewer than 21 spells, many found in the most improbable of places. As always, Level 9’s ability to squash a crazy amount of game into 48 K is impressive — maybe a little too impressive. Combined with all of the bugs, it’s enough to make the game as a whole all but unsolvable even if playing straight from a walkthrough, what with all of the wandering characters constantly mucking with everything, never being where you want them, and always stealing items from you just when you were about to use them for something. I’m told that the whole thing is eventually revealed to have taken place in a simulacrum of a fantasy world, similar to the ending of Adventure. Ah, well… Level 9 had ignored that original ending in Colossal Adventure in favor of grafting a bunch more gameplay onto the end, so I suppose they earned the right to use it here.

Knight Orc received a notably cool reception in British adventuring circles, with reviewers dwelling at some length on how all but impossible it was to actually get anywhere with it. Others seemed put off by the sheer bloody-mindedness of it all, apparently preferring their fantasy fantastic and their heroes heroic, while plenty more just wanted the sort of traditional adventure game that Knight Orc most definitively was not. Even the pictures that were included with the 16-bit versions sparked a surprising amount of vitriol. Rather than resorting to vector graphics again or drawing directly on the computer, Level 9 digitized a set of watercolor paintings provided by Godfrey Dowson. The end results have a soothing, almost Impressionistic quality that clashes with the carnal tone of the game itself, but they hardly strike me as worth getting so upset over. They’re rather nice pictures really.

Nor was Knight Orc destined to be the big break Level 9 dreamed of in North America. A milquetoast Computer Gaming World review made the very cogent observation that the puzzles “are too uneven” — “When random bad luck can spoil a well-thought-out solution, it’s hard to be sure if you’re on the right trail.” — and damned the game with the faint praise of “above average.” Most of the other magazines didn’t even notice Knight Orc, which like its two predecessors vanished quickly from the store shelves.

And so now all of Level 9’s games for Rainbird had proved to be commercial disappointments, while the British gaming press was now indulging in unabashed schadenfreude, saying that Level 9 had lost their mojo to their intra-label rivals Magnetic Scrolls. The Rainbird/Level 9 relationship collapsed under mutual recriminations. Level 9 said with some degree of truth that Rainbird had always favored Magnetic Scrolls, had given their games exactly the sort of promotional push, especially in North America, that Level 9 had never received. They claimed that any enthusiasm Rainbird had had for adventure games not from Magnetic Scrolls had ended with the departure of Tony Rainbird. Rainbird could reply with an equal degree of truth that Level 9 hadn’t given them all that much to promote: just two musty classics collections and one radical departure from their past that was wildly original but also kind of unplayable. A middle ground between retread and innovation would have been welcome at some point. By mutual decision, the two parted ways. Level 9 was now fully on their own again, forced to publish and market their next game for themselves. By 1987 that was a fairly uncomfortable place for a little family shop like theirs to find themselves in, but needs must. They would never regain the commercial mojo they had lost — or had stolen from them — in 1986.

Their best games, however, were actually still in front of them.

I’ve had a difficult relationship with Level 9 since starting this history. As the major interactive-publisher I knew least, they were the one I was most excited to learn more about, but they’ve left me feeling again and again like Charlie Brown on the football field, as their big ideas and interesting fictional concepts proved again and again to be riddled with nonsensical puzzles and fundamental issues of playability. I was ready to give them one final article today and be done with them. But then some of you encouraged me to have another look, I noticed that the games that followed Knight Orc were substantially better reviewed, and I came across this welcome statement from Pete Austin in a late interview:

It is worth saying that in the later ones when it is finished we play through it and we now have about a month’s play testing and we do take the results of the play testing quite seriously. This is from Gnome Ranger [the game that followed Knight Orc] onward. We also, where people find puzzles hard, put hints around the place or make them easier.

It seems that Knight Orc‘s obvious failings finally prompted changes at Level 9. I’ve investigated some of their games still to come, and found works that incorporate many of Knight Orc‘s innovations into more sober, accessible, solvable designs. I’m thus happy to say that there are still articles worth writing about Level 9.

In the meantime, I do encourage you to have a look at Knight Orc. It’s still one of the most unique text adventures I’ve ever played, and you can experience that uniqueness more than well enough in the reasonably playable first part. Whatever else you can say about it, it’s good for one hell of a laugh.

(Sources: Retro Gamer 6, 7, and 57; Amtix of June 1986; Page 6 of July/August 1988; Your Computer of October 1987; Questbusters of November 1987; Sinclair User of May 1985; ZX Computing of September 1986; Crash of February 1988; Amstrad Action of May 1986; Computer and Video Games of July 1986; ACE of December 1987; Computer Gaming World of April 1988.

Feel free to download Knight Orc to give it a try. The zip file contains two versions of the game: as a disk image for use with an Amiga emulator, or, in the “game” folder, as data ready for use with a Level 9 interpreter that’s available for many platforms. Open “gamedat1.dat” in the interpreter and everything should Just Work from there.)