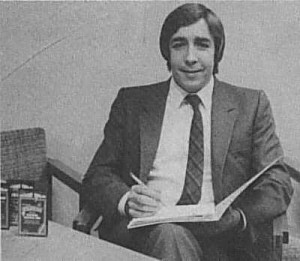

The young and brash Tony Rainbird had never made a good fit with the rigid management structure of British Telecom. Thus when in late 1986 he suddenly left the hot new label he had formed barely a year before it came perhaps as more of a surprise to outsiders than to said label’s inner circle. The question of whether he jumped or was pushed will probably never be publicly answered. Asked later about his departure, Tony’s answer could be seen to imply either: “For about 60 different reasons, really, but they added up to a lack of respect for the senior people in the British Telecom hierarchy.”

In a telling indication of just how close he had become in a very short while with his favorite signees, Tony actually moved his office into those of Magnetic Scrolls for a while after leaving British Telecom, working as a management consultant and accountant and even occasionally pitching in on game design in between taking other consultancy gigs for other companies. Meanwhile the engine he had set in motion at British Telecom would continue to chug along apparently business as usual for quite some time; Tony himself noted that he “had recruited a very good team that were well able to take over.” In time, however, the loss of Tony Rainbird’s drive and vision couldn’t help but have an effect on his namesake label. Their most successful games and developer relationships by far would prove to be those initiated during his own brief tenure. By 1988 a distinct state of diminishing returns would set in, with major consequences for Magnetic Scrolls. In the meantime, though, they found a patron of a very different stripe in Michael Bywater, whose presence looms not only over the history of Magnetic Scrolls but also the late history of Infocom.

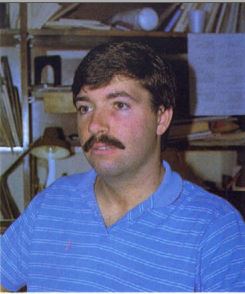

For many Michael’s chief claim to fame was and is his longstanding friendship with Douglas Adams. This state of affairs has often irked him, and understandably so, given his own considerable accomplishments. The pair’s long, occasionally tempestuous relationship dates back to the early 1970s, when both were reading English at Cambridge and performing with the Footlights, the legendary comedy troupe whose rolls have included the likes of Graham Chapman, John Cleese, and Eric Idle of Monty Python amongst many other prominent comedians, actors, and writers. Michael’s schtick was to perform ribald comic songs, self-penned or parodic, whilst accompanying himself on piano, while Douglas performed as a comic actor — not, it must be admitted, a very good one — and wrote skits. They bonded — or not — over a girl that they both fancied. Michael won the romantic competition, marrying (and eventually divorcing) her, but Douglas was never one to hold a grudge. When he hit it big at decade’s end on the back of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, he happily supported his still-struggling old friend for a time as Michael slowly built a career of his own as a working writer for many forms of media: film, television, newspapers, magazines. Michael’s own, admittedly more modest sort of big break came when he was hired as a contributing editor at Punch, a slightly long-in-the-tooth but still respected magazine of politics, culture, and, most of all, satirical humor. In addition to that job, he wrote regular columns for The Observer newspaper and MacUser magazine.

Like Douglas, Michael had a fascination with technology, particularly computers, particularly particularly Macs. Indeed, the two old friends had much in common. Both were interested in just about everything, priding themselves on keeping one foot planted in the world of art and literature and the other in that of science and technology. Both knew intimately and drew liberally from the great British tradition of absurdist, satirical comedy that reaches back from Monty Python through P.G. Wodehouse (always Douglas’s favorite humorist) to Jonathan Swift. Both were great raconteurs who loved nothing more than to be the center of attention at a party; Michael was the hit of many a lavish Douglas Adams shindig with his piano playing and his comic songs. And both strongly held plenty of opinions that they weren’t shy about sharing with each other. Their sparring matches about every subject under the sun became famous amongst their circle of acquaintances. In the midst of one heated exchange, Douglas picked up a fish from his plate at a fine French restaurant and smacked Michael across the face with it, leaving the latter as one of the few people in the world able to make reference to a certain old British cliché from actual experience. Still, their arguments did no apparent lasting damage to their friendship.

Quite the contrary: Douglas believed deeply in Michael’s literary talent and found him personally inspiring. At the time that Magnetic Scrolls was hitting it big with The Pawn, Douglas was struggling with his fifth novel, Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, his most earnest attempt ever to separate himself from a legacy that often felt to him like a millstone and define himself as a writer of general note, not just the guy behind that wacky Hitchhiker’s Guide stuff. The titular detective is based in whole or in part on Michael: in the words of Douglas’s biographer Nick Webb, “plump, bespectacled, addicted to cigs, delinquent about money, randy yet unfulfilled, given to gnomic utterances, exploitative, guilty, not entirely wholesome, irritatingly right, and possessed of high-powered but usually non-linear thought processes.” In between using him for inspiration and as a sounding board and editorial consultant for his own writing, Douglas sometimes found writing gigs for Michael to handle on his own, sometimes out of mere loyalty to his old mate and respect for his talents, sometimes and less magnanimously as a surrogate to take on projects he’d gotten himself into and didn’t want to follow through on.

It was largely the latter motivation that led Douglas to get Michael his first gig as an author of interactive fiction. Douglas had convinced Infocom that they would follow up the Hitchhiker’s game not with a direct sequel right away but with a different sort of collaboration, a slice-of-life comedy about the petty bureaucratic tyrannies of modern life. What with his enthusiasm for the project having begun to flag almost immediately after agreeing to do it, he eventually enlisted Michael as a sort of British-humorist surrogate to take it on. The latter thus traveled to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in late 1986 to spend a month holed up in a hotel room near Infocom’s offices with programmer Tim Anderson, writing or rewriting much of the text in Bureaucracy. The full story of Bureaucracy is a long one that we’ll get to in a future article. For now, suffice to say that Michael knew interactive fiction quite well on account of his work on that game as well as his friendship with Douglas Adams when he first met Anita Sinclair at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas in January of 1987.

Michael was there to cover the latest and greatest in the world of technology for his various journalistic beats. Anita was there to promote The Pawn, still her company’s only released game, as well as to preview their next, another fantasy romp to be called Guild of Thieves. The two hit it off immediately — Michael still calls Anita “one of the most fascinating and brilliant women I’ve ever met” — and were soon a romantic item. By virtue of, as he himself puts it, his “sleeping with the boss,” Michael became a significant figure at Magnetic Scrolls for the two years or so that their relationship lasted. Leaving their romantic attraction in the realm of the personal where it belongs, the reasons for the professional attraction aren’t hard to suss. Michael was witty, urbane, erudite, and literary down to his bones, exactly the way Anita ideally envisioned Magnetic Scrolls. Anita, meanwhile, was building little virtual worlds out of text and code, something that struck Michael as delightfully futuristic and exciting. They also had something else in common: Michael’s career was destined to be discussed all too often through the prism of Douglas Adams, just as Anita’s career with Magnetic Scrolls would be through that of Infocom. By way of fair warning, I should say now that I’m going to be doing a lot more of both in this very article.

We’ll get to Michael’s creative contributions to Magnetic Scrolls momentarily. First, though, let’s talk intangibles. An association with Michael Bywater, whether personal or professional, usually brought with it an association with his good friend and occasional patron Douglas Adams. Thus Anita was soon living next door to Douglas in Islington and attending many a party at his flat. For Magnetic Scrolls, a relationship with Michael and Douglas led naturally to the furtherance of a relationship with Infocom that had already been tentatively established at the end of 1986, when Anita attended Infocom’s Christmas party and met most of the Imps for the first time. The two companies soon became quite chummy with one another indeed, visiting one another’s offices any time they had an excuse to travel across the ocean. Both have stated on many occasions that they genuinely, personally liked one another, enjoyed socializing together and talking shop about the esoterica of parsers and world models that almost no one else in the world was struggling with with the same degree of seriousness. There was occasional talk amongst the more paranoid souls at both companies of trade secrets and the theft thereof, but the two companies’ core technologies were built on such different lines that the idea was almost inapplicable. Their conversations tended to be more philosophical and general than technical and specific.

The overall market for text adventures was undeniably dwindling by the late 1980s, but if anything this only served to strengthen the relationship. Anyone buying a Magnetic Scrolls or Infocom game from 1987 onward was almost by definition a member of the hardcore who would happily buy from both companies; it wasn’t a zero-sum game like, say, two competing word-processor makers. On the contrary, each could do something for the other. Infocom, after largely ignoring the world outside of North America for years, very much wanted to establish a presence in Europe and especially Britain, not least because their North American sales were continuing to trend so relentlessly downward; they could very much use Magnetic Scrolls’s advice and public support in making this international push. And Magnetic Scrolls craved the cachet that still clung to the Infocom brand, the legitimizing effect brought to their little operation by, say, a joint press conference in London with Dave Lebling. The public relationship was always a bit asymmetrical, with Magnetic Scrolls always pretty clearly the junior partner; Magnetic Scrolls strewed their games and feelies with references to Infocom and the Imps, as if to brag about the connection, while, tellingly, Infocom never bothered to reciprocate. There are also some odd instances of apparent wishful thinking from Magnetic Scrolls’s side, such as Anita Sinclair’s claim in late 1987 that she had actually brokered the deal between Infocom and Michael Bywater that finally got Bureaucracy finished, a claim that just doesn’t hold water in light of the established historical timeline. Still, Magnetic Scrolls, alone amongst the other makers of adventure games, had won for themselves a seat at the table with the best in the business.

Indeed, Magnetic Scrolls continues to benefit from the Infocom association to this day, being widely regarded — occasional naysaying fans of the admittedly longer-lived and more prolific Level 9 to the contrary — as the “British Infocom.” Given that appellation, it’s worth noting that Magnetic Scrolls’s games are far from clones of Infocom’s. There is first of all their very British Britishness, which actually played very well in North America, where there was always a substantial demographic overlap amongst fans of Monty Python, fans of Douglas Adams, and fans of text adventures. If anything, Magnetic Scrolls would play up the Britishisms even more in the games that followed The Pawn, to the point that it could start to feel painfully self-conscious on occasion. They found that doing so made their games stand out on foreign shelves; it just made good commercial sense.

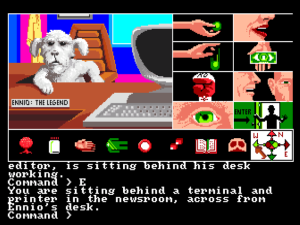

But there are also less immediately obvious differences. Magnetic Scrolls, especially in their early games, didn’t embrace storytelling to anywhere near the degree that Infocom had been doing for years now. Their games remained largely text adventures rather than interactive fictions, setting your anonymous avatar loose in a big, interesting environment and just letting you get on with it, collecting stuff and using it to solve puzzles. This was reflected in their development system, which emphasized the simulation aspect of virtual worldbuilding much more than did Infocom’s games. Every object had a weight, a size, even a strength — to determine what would happen if you tried to “break” one item with another — and this data was maintained quite scrupulously in comparison to Infocom’s more relaxed approach to realism. At its best, this could lead to interesting and unanticipated emergent effects. Michael Bywater has told the story of an experimental in-house game that had a rat which could, like all items in the game, be frozen in a tub of liquid nitrogen. Afterward, and much to the surprise of everyone involved, the frozen rat’s tail could be used to slice open a sack in lieu of the knife that had been put in the game for that purpose.

More commonly, though, the emphasis on simulation just leads to you the player carrying around a lot of objects given arbitrary labels like “broken” which the game doesn’t seem quite certain how to deal with. Modern interactive-fiction author Emily Short describes the dangers of out-of-control simulationism:

The premise “the world will have everything!” is not a story concept. It’s a recipe for disaster. It’s much better to go in with one specific thing you want to achieve, and execute that really well. If that happens to include building out a liquid system or weather that changes over the course of the story, that’s fine. But you need to have a reason for everything you put in, or it will just get out of hand.

The hard truth that all-encompassing simulationism is more interesting for the programmer than it is for the player would seemingly begin to dawn on Magnetic Scrolls as time went on, but never as fully as it did on Infocom. While Infocom had years to build on their own early games with their hunger, thirst, and sleep timers, harshly realistic inventory limits, and even occasional randomized combat, Magnetic Scrolls’s career of active game-making was dramatically compressed in comparison: less than half the time, about 20 percent the total completed games.

There were also marked differences in process as well as philosophy. Infocom never abandoned their conception of their games as works of one or at most two authors, like the novels they were so self-consciously styled to echo in so many ways. As time went on and the dream of Infocom as pioneers of a new genre of mainstream literature began to fade, they only clung to this vision all the tighter. Beginning with Leather Goddesses of Phobos in 1986, Infocom began putting each game’s author right there on the cover in the place once occupied by the genre tag. When circumstance and happenstance forced collaboration on them, as in the case of Bureaucracy, their internal processes, so efficient in so many other ways, just didn’t seem to be able to deal with it — a failing that has been individually raised as one of the company’s most persistent unsolved problems by quite a number of insiders. Each Magnetic Scrolls game, by contrast, was very much the product of a team process. Artists, designers, programmers, writers, literally the whole staff of the company — all joined in to contribute and complete the game.

At the same time, though, when it came to the most important collaboration of all — the testing process — Magnetic Scrolls trailed far behind Infocom. Too much of the time their games have that echo-chamber quality of works that have never been experienced by anyone other than the people who made them. As I’ve said quite a number of times before, it’s first and foremost a tribute to Infocom’s testing regime that their games managed to be so consistently good as they were. Magnetic Scrolls, with no testing regime to match, couldn’t hope to match Infocom’s level of polish. In addition to a dribble of typos and textual glitches that you just wouldn’t see in an Infocom game, every one of their games seems to be marred by at least one or two Really Bad Ideas that thorough testing would have done away with. “The testing, debugging, and refining process can take forever, but you have to draw the line at some point,” Anita once stated. “Otherwise the game would never see the light of day.” Fair enough, but one could wish at times that Magnetic Scrolls had been willing to draw their line just a bit closer to that infinity.

That said, Magnetic Scrolls’s second game, Guild of Thieves, did manage to put a much better foot forward than The Pawn, becoming in the process their most prototypical game if arguably not their absolute best, the logical first choice for anyone who wants to get a taste of what they were all about. As he had for The Pawn, Rob Steggles during a break from university sketched out virtually the entire design on four pages of closely spaced notebook paper in a matter of a few days, then left it to the rest of Anita’s little team to realize it. The game even took place in Kerovnia, The Pawn‘s fantasy world. The final result, however, turned out much better. Rob Steggles himself admits today that Guild of Thieves “was certainly a lot more accessible and coherent than The Pawn.” For all the praise The Pawn accrued in the press, back-channel communications — quite possibly including some feedback from their new mates at Infocom — must have led Magnetic Scrolls to realize that that game wasn’t quite an ideal adventure. “One of the things people objected to about The Pawn was our weirdness,” said Anita at the time of Guild of Thieves‘s release. “We’ve taken a lot of our weirdness out of Guild of Thieves.” Conflating fairness with difficulty in a way that was depressingly common at the time, Anita declared that the new game would be much “easier,” “aiming at a much more straight-forward market. I mean, you won’t have to be an avid adventurer to enjoy this product.”

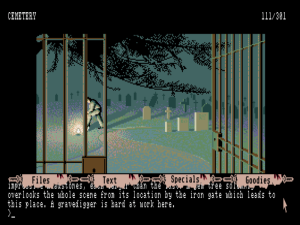

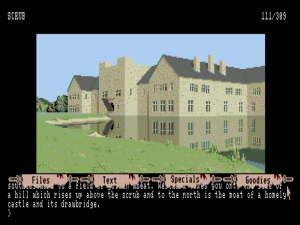

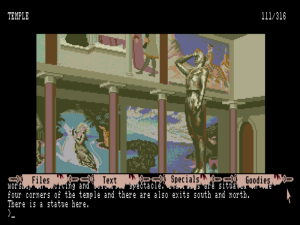

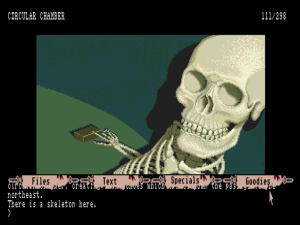

Magnetic Scrolls’s second game Guild of Thieves may just contain artist Geoff Quilley’s best work for the company.

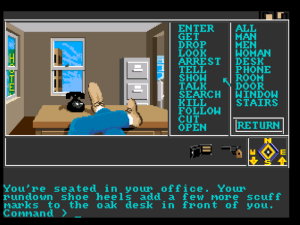

Well, I’m not quite sure about that last statement, and I certainly wouldn’t characterize Guild of Thieves as “easy.” I would, however, characterize it as a very, very good old-school adventure game, one of my absolute favorites of its type. You play an apprentice thief whose trial of initiation into the Guild entails looting a castle and its surroundings of valuables. Even in 1987 its plot — or almost complete lack thereof — marked it as something of a throwback, an homage to classic formative works like Adventure and Zork. You’re free to roam as you will through its sprawling world of a hundred or more rooms right from the beginning, solving puzzles and collecting treasures and watching your score slowly increment. Most of the individual puzzles are far from overwhelming in difficulty; for the most part they’re blessedly fair. The difficulty is rather more combinatorial. Guild of Thieves, you see, is a very big game. You’re quite likely to lose track of something in the course of playing it, whether it be a forgotten treasure or an unsolved puzzle. Still, it’s only when you reach the end game, which entails penetrating the Bank of Kerovnia to recover all of the treasures you’ve been “depositing” there for points, that a few of the puzzles begin to push the boundaries of fair play. (Text adventures and banks apparently just don’t agree with one another: one of Infocom’s most famously bad puzzles took place in the Bank of Zork in Zork II.)

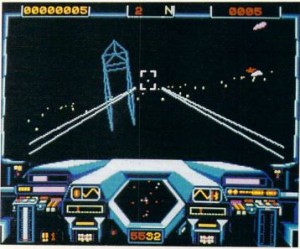

Guild of Thieves is old-school in conception, but it’s not without Magnetic Scrolls’s trademark technological inventiveness. The ability to simply “go to” any location in the game in lieu of compass directions and the associated ability to “find” any item is more than just an impressive gimmick; it’s a huge convenience for the player, one might even say a godsend given the sheer sprawl of the game. Magnetic Scrolls’s much-vaunted “data-driven” model of adventuring also bears some useful fruit in the ability to reference objects by kinds. If you are, for instance, carrying a bunch of billiard balls, you can drop them all — and nothing else — by simply typing, “drop balls.” If the parser in Guild of Thieves still isn’t quite as flexible and responsive as Infocom’s — it guesses at your meaning occasionally to sometimes unfortunate effect, and its error messages are nowhere near as comprehensive and useful — it’s very, very close, the closest anyone would ever manage during the era of the commercial text adventure. Certainly it’s the first and only to make one sit up and say from time to time, “Gee, I wish I could do this with the Infocom parser.” That Magnetic Scrolls did this while also shoehorning lovely graphics and a much larger world than was typical of Infocom into the humble little Commodore 64 gives considerable credence to the British press’s oft-repeated assertion that their technology was actually much better than that of Infocom.

The prose in Guild of Thieves is mostly fairly matter of fact, with just the occasional flash of whimsical humor. A fellow thief who’s also casing the place for treasure provides the most frequent and amusing source of comic relief. But otherwise much of the game’s personality and the bulk of its humor are off-loaded to What Burglar, a sort of Guild newsletter largely authored by none other than Michael Bywater. Michael:

It was the time of the breakdown of trades unionism in Britain and there were all these terrible dinosaurs representing The Working Man and in reality just buggering up The Working Man’s life with rules and restrictions and terrible tortured constipated bureaucratic language and all the rest of it… and I thought it would be fun to apply that mindset — of truculent respectability — to something which wasn’t in the slightest bit respectable. And it just went from there.

The humor’s somewhat hit and miss, with more than a little of that “I’m trying ridiculously hard to be very, very British” quality that occasionally dogged Magnetic Scrolls in general, but when it hits it hits very squarely indeed. I particularly like the Guild’s reaction, so typical of any hidebound bureaucracy when its comfortable status quo is threatened, to members who decide to jump ship: “Beaker said he was ‘sick as a macaw’ with young apprentices training at the Guild’s expense and then ‘going off the straight and narrow — becoming doctors and shopkeepers and such.'”

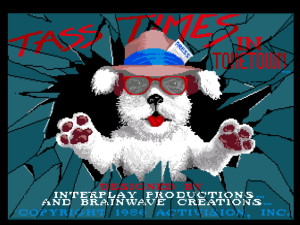

While creating Guild of Thieves was a relatively smooth process for the close-knit little group of friends who had already created The Pawn together, the process of creating Magnetic Scrolls’s third game was so torturous that it found expression in the very name of said game. Originally titled Green Magic, it was to be a contemporary urban fantasy written and designed by Anita’s sister Georgina, author of the novella that accompanied the Rainbird release of The Pawn. If Guild of Thieves was Magnetic Scrolls’s Zork, Green Magic was to be their Enchanter, its puzzles revolving around collecting spells and using them to solve more puzzles to collect more spells and… you get the picture. As Anita later put it, though, “Everything seemed to go wrong that possibly could.” Whether despite or because of the familial connection, Georgina just never got on with the team who would be responsible for implementing her ideas, leading to lots of tense conversations and lots of fruitless wheel-spinning on the part of just about everyone involved. Meanwhile the design seemed to wander off-course almost of its own accord; what was supposed to have been a game about spell-casting ended up with just five under-used spells in it as other puzzle ideas kept taking precedence. As the changes came and went and the cost mounted it started to look more and more like a bad penny that just wasn’t worth saving. “I think if you’d taken a poll at Magnetic Scrolls a few months ago about whether we would continue with it or not despite the work we’d already put into it,” said Anita just before its eventual (miraculous?) completion, “just about everyone would have voted to drop it completely.” At last Georgina delivered a final draft and pronounced herself done with it. In Anita’s opinion the writing still just wasn’t very good: “When the first ‘finished’ version came in, I felt like picking it up and giving it a good shake. It was rather twee.”

Christmas 1987 was looming, and Rainbird was expecting a second game from Magnetic Scrolls for the year. Anita therefore once again enlisted her beau Michael Bywater. Initially she asked him to simply polish up some of the worst parts of the text, but Michael, an established professional writer, was understandably not excited about becoming Georgina’s editor. Working in a similar creative frenzy to the one that had yielded the finished Bureaucracy, fueled by coffee and cigarettes and Anita’s encouragements, he rewrote every bit of text in the game in a matter of a few weeks. Michael:

The process was quite interesting because the game logic had already been coded and only the descriptors were changeable. For example we might have had, at the logical level, X cuts Y and A opens & B comes out. Well, you could start with “The fairy sword cuts the cobweb mantle and the magic room opens and Euphorbia the tinkling gnome dances out.” You might think, no, we’ll change all that and have “The enraged ogre’s penknife cuts the imbecile mountaineer’s safety-rope and his anorak tears open and his lunch falls out,” which is obviously a completely different narrative passage, but the underlying structure is the same. And that’s basically all I did. I got the structure and changed the way that structure was enacted.

As for the game’s new title, it was a natural outgrowth of the black humor that had now been surrounding it for some time amongst its would-be creators: Jinxter.

Sometimes Jinxter echoes just a bit too closely the work of Michael’s friend and patron Douglas Adams. See for instance this part that pays homage to Infocom’s Hitchhiker’s game on perhaps one or two too many levels:

>get keyring

As you bend to pick up the keyring, a sudden tremendous roaring fills your ears, like the roar of the sea. It is not, however, the roar of the sea, but the roar of an inhumanly, abominably, unfairly colossal bus. Your response to this hideous threat to your existence is to stand immobile with your mouth hanging open.

>examine bus

You are about to die. Your job is to come to terms with the situation. It's pointless to try to examine anything.

>run

No time for that now. There is a squeal of brakes, followed by a sickening dull cliche as a small dog (which was innocently munching on a passing microscopic space fleet) is propelled into the Land Where Doggies Are Eternally Blessed by a large bus. You, on the other hand, are propelled to the kerbside by a firm grip on your collar, and, when you recover your so-called "senses," you see a large, pot-bellied figure in a herringbone overcoat hovering a couple of feet above the pavement munching on a cheese sandwich.

Yes, I’m afraid it now once again becomes hard to talk about Michael Bywater without using Douglas Adams as the chief point of comparison. Dave Lebling once described Michael as “writing like a somewhat more acerbic Douglas.” Certainly Michael’s humor lacks the humanity of Douglas Adams at his best. If Douglas is laughing at the absurdities of the universe and the people that inhabit it, Michael is laughing at you, out there wasting your time with this silly adventure game. Douglas liked his haplessly average hero Arthur Dent so much that he just kept getting him out of scrapes for book after book. When he finally killed him at the end of Mostly Harmless, he regretted it almost from the moment the book went to press; this senseless murder, which he attributed largely to depression and existential angst following the death of his father, pained him for the rest of his life. Jinxter‘s equivalent to Arthur Dent is your avatar, rescued from the death by large bus described above by forces beyond her ken to save the world. When she gets done doing that, Michael sends her back to be flattened after all; this marks the “winning” ending of the game (Scorpia was once again not amused). Needless to say, Michael has never expressed one instant of regret.

The art in Jinxter is more pixellated and less dazzling, likely a result of the time crunch under which it was finalized. Ah, well, Michael Bywater’s prose perhaps dazzles enough.

Michael Bywater’s writing is sometimes ostentatious and sometimes cuttingly cruel but almost always wickedly clever. In fact, the prose in this badly flawed game is almost enough to gambol away entirely with my critical judgment. There’s some Carrollesque wordplay:

>examine roll

The plum roll has the plum role in the entire game, but otherwise is just a red herring.

There’s some adroitly adept alliteration:

>examine fire engine

The furiously flashing fire engine sports a splendid ladder and a fanfare for forcing foot-travelers to flee from its feverish fire-dousing fury (all fundamentally fictitious flapdoodle, of course; for, though finely-forged, this fire engine is a fake, fixed firmly in the fairground).

There’s some unlikely metaphors that would make Dickens proud:

>examine stationmaster

This old buffer has, after years of contact with trains, become at least 50% train himself, as is obvious from the way he steams and puffs and whistles his way around his domain.

There’s even a bit of sly innuendo to remind you that Jinxter came from the company that made the protagonist of their first game a pothead.

>examine harmonica

This is the Larry Adler Special Chromatina, as featured in the movie "Blow Mah Organ, Big Boy." If you put it in your mouth and blow, it makes a happy sound. Same old story, huh?

But we really do need to talk about the flaws now. They’re strangely well-hidden, easy to overlook at first in light of the oft-crackling prose. Then in the final stage you penetrate the castle of the villain, only to get yourself thrown into the dungeon. There comes a puzzle at this point that neatly illustrates everything that went wrong far too often for Magnetic Scrolls. Here’s the setup:

Dungeon

This room has been carefully decorated in traditional dungeon style, and thus is disgusting. Damp drips from the crumbling walls, to which a set of heavy manacles are immovably pinioned. Nearby hangs a rope which appears to be attached to a wooden hatch.

>lift hatch

Try as you might, the hatch won't budge.

>examine rope

This old, rotted rope is attached to the wooden hatch. Looks like you pull on the rope to get the food in the hatch. If there were any food in the hatch, that is. Anyway, you get the picture.

>pull rope

Interesting... as you pull on the rope, the shutter rises to reveal one of those little "dumb waiters." That is to say, a little space with another shutter on the far side. It looks as though the outer shutter closed by means of some interlocking mechanism as the inner shutter opened, probably so that the unfortunate prisoner could get at his food without ever being able to glimpse the outside world.

After a few moments, the weight of the shutter becomes too much for you; you let go of the rope, and the hatch crashes shut.

>tie rope to manacles

You raise the shutter with the rope, which is now long enough to reach the manacles. Once tied, the taut ropes keeps the hatch shutter open.

>enter hatch

Dumb Waiter

You are compressed like toothpaste in a tube into this pigswill-stinking compartment between two hatches, one leading to the dungeon, the other to the kitchen. In the good old days, at this point, a prisoner would have flung open the hatch and eaten you.

>open outer hatch

Try as you might, the outer hatch won't budge.

>close inner hatch

Try as you might, the inner hatch won't budge.

The obvious problem here is how to get the outer hatch open — or the inner hatch closed, which amounts to the same thing given the mechanism that links them. You have quite a collection of items in your inventory, but for purposes of this puzzle the relevant ones are a top hat, a candle, and a book of matches. Feel free to give it some thought before proceeding if you like, although I’m not sure it will do you much good.

So, the solution is to put the top hat below the rope that’s tied to the manacles, put the candle in the top hat so it doesn’t fall over, light it with a match, dive into the hatch, and wait for the candle to burn the rope enough that it breaks. Now, this makes no sense on multiple levels. It’s not a bad puzzle because it’s contrived; most adventure-game puzzles, including just about all of the classics (hello, babel fish!), are contrived, and if you can’t accept that you’re unlikely to be able to accept playing adventure games. It’s a bad puzzle because it just doesn’t make any sense given the consensus physical reality the player expects to share with the game. How on earth can a top hat as wide as my head hold up a narrow little candle? And if it’s some weird, fat candle — the game never describes it as anything other than “a stick of wax with a wick up it” — it should be more than stable enough to stand on its own, sans hat. And can even an “old rotted rope” that must be at least a foot or so above the candle, given that it’s tied to manacles mounted on the wall, really be burned by it enough to break? And then why can’t I just eliminate the middle man, as it were, and light the rope itself on fire? Well, actually, I can, but I just get the message that “The rope burns away” before I can do anything else, an emergent effect of the generic simulationism of which Magnetic Scrolls was so proud. As the cherry on top of this delightful shit sundae of a puzzle, the whole thing is subtly but persistently and thoroughgoingly bug-ridden if you head off on anything but the game’s arbitrary right track. Burning the rope itself directly, for instance, leaves the game in hopeless confusion about whether it’s actually there or not anymore, while tying the rope to other stuff gives a wonderful lesson on all of the ways that ropes in adventure games are notoriously difficult to implement, to such an extent that the advice of many long-time interactive-fiction authors to beginners on the use of them can be summed up in one word: “Don’t.”

As bad as that puzzle is, there’s one that follows that may be even worse, a sliding-blocks puzzle implemented in text — a questionable premise to begin with — that has you moving a bunch of numbers around with no clue whatsoever of what configuration you’re intended to bring them into. This compulsion so many text-adventure designers had to make the final sections of their games really, really hard — i.e., unfair — is frustrating to say the least. As Graham Nelson amongst other interactive-fiction critics has often noted, endgames should if anything ratchet down in difficulty as the player gets closer to victory. By the time she gets to the final puzzle or two, she’s so close she can taste it; she just wants to win. The game should do her that kindness by not throwing impossible barriers in her path.

But you still haven’t yet heard the worst of it with Jinxter. I thought there was no capriciously cruel thing that an adventure game could still do to leave me shocked, but when I played Jinxter recently for the first time it proved me wrong. Unless you’ve been playing straight from a walkthrough or have been otherwise forewarned, your first time through the game is almost guaranteed to end like this:

Hallway

The spiral staircase leads downwards from this hallway, which, from its atmosphere of nervous anticipation, would seem to be some sort of waiting room. There are two Gothic doors set into the far wall. You begin to realize that the architect of this place had something of a one-track mind. You can hear a fearful fracas taking place behind the doors.

>open left door

The left door is now open.

>enter left door

Wrong, wrong, wrong. That was a BAD move. Bet you're wishing you'd gone through the other door, aren't you? Well, it wouldn't have helped. Not one bit. The fact is, you just weren't lucky enough to get out of this scrape. Not this time. Not here. Not now. Had you been a little further up on the luck scale, so to speak, perhaps things would have been different. As it is, they're not, but you are, different that is. You're out of luck. Totally. Completely. It's all gone, and so have you. Goodbye.

It seems that the game has been keeping track of your depletable store of luck all along. Many things that seemed like close calls just added to the game for atmosphere — like the piece of barbed wire that almost hit you in the face when you cut through a fence way back at the beginning — have been depleting this store. Use luck one time to get out of a scrape, and you’re toast when it comes to the endgame. Now you get to play it all over from the beginning, trying to identify and head off these situations; you’ll find out how successful you were only when you get back to the scene above. I’ve played a lot of adventure games, but I’m not sure I’ve ever seen one quite as heartless as this one — and that, my friends, is saying a lot. Certainly I’ve never seen a game revel in its cruelty as much as Jinxter does in the paragraph above.

The question I’m left with is Why? Cruel tricks were usually included to pad a game’s length, but Jinxter, like its predecessors, is a big game already, with lots of puzzles and plenty to see and do. One wonders why no one told Magnetic Scrolls that torturing the player like this was a really, really bad idea, not exactly the sort of thing that sends her whistling happily off to the shop to buy the next one. The most logical conclusion, especially given the rush to complete Jinxter, is that no one told them because no one else ever even played it before it shipped. In one or two interviews Anita mentioned Jinxter‘s luck mechanic in passing, bizarrely spinning it as sort of progressive design choice, a way to let beginning players see more of the game without getting stumped by the hardest puzzles. One could reply to that simply by pointing her to Wishbringer, a game that uses a similar mechanic in a way that leaves the player who’s taken the easy way out once or twice with a satisfying winning screen that encourages her to play again for a better score rather than cutting her off at the knees for failing to solve puzzles she didn’t even know existed. About the only thing Jinxter encourages a beginning player to do is not to play any more text adventures.

Speaking of which: Guild of Thieves sold well, but somewhat less well than The Pawn, while Jinxter registered another substantial drop-off from its predecessor. This steady downward sales trend would continue for Magnetic Scrolls, who would never manage another game with anything like the commercial impact of The Pawn. But their games themselves would remain consistently interesting if also consistently inconsistent, and we’ll continue to follow them in future articles. As for Michael Bywater, he wouldn’t have a hand in any of the Magnetic Scrolls games to come, but he’s definitely a character we’ll be meeting again around here for other reasons.

(Sources this time are largely the same as those from my last article. Also: a fascinating if confused and ill-advised article by Andy Baio and the comments therein and Michael Bywater and Steve Meretzky’s joint appearance at an event organized by Yoz Grahame circa 2005. And two biographies of Douglas Adams: Nick Webb’s Wish You Were Here and M.J. Simpson’s Hitchhiker. You can download the Amiga versions of Guild of Thieves and Jinxter from here if you like, or download the games and an interpreter to run them on many modern platforms from The Magnetic Scrolls Memorial.)