Scaffold

Whoever threw this place together wasn't too worried about permanence. Tin walls rise on flimsy studs to a ceiling that sags under its own weight. It reminds you of a prefab tool shed, several stories high.

You're standing beside a monstrous conglomeration of pipes, compressors and pressure valves that fills most of the building.

A stairway leads downward.

>d

You descend the stairway.

Bottom of Scaffold

A maze of plumbing rises before you like the back of a giant refrigerator. Stairs lead up to a scaffold overlooking the equipment. Turning south, you see a closed set of sliding doors, with a small box and a loudspeaker mounted on the wall beside them.

>open box

You swing the box open.

A toggle switch and a red button are mounted inside.

>turn on toggle switch

You turn on the toggle switch.

The loudspeaker emits a burst of static, then a steady hiss.

"Zero minus two minutes."

>push red button

You push the red button.

With an electric whirr, the heavy doors slide open.

"Zero minus ninety seconds."

>s

South Beach

The waters of a peaceful lagoon reflect the tropical dawn like a fiery mirror. A few stars are still visible in the rosy sky.

The glorified tool shed dominates this little island, leaving room only for a narrow strip of sand that curves to the northeast and northwest. A red button is mounted on the wall beside the open sliding doors of the shed.

"Zero minus one minute."

>ne

You follow the curve of the shore.

East Beach

Palm trees far across the lagoon stand in dark relief against the eastern sky. The shore continues northwest and southwest, around the equipment shed.

"Zero minus thirty seconds."

>nw

You follow the curve of the shore.

North Beach

A square wooden extension juts out of the side of the building, stretching away across the lagoon as far as you can see.

The beach continues around the equipment shed to the southeast and southwest.

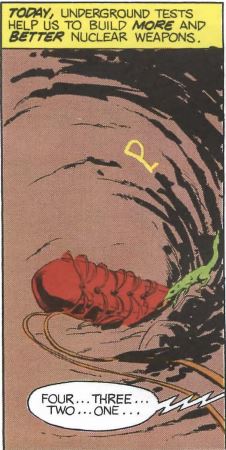

"Five. Four. Three. Two. One."

Your tropical vacation is cut short by a multimegaton thermonuclear detonation, centered in the nearby equipment shed.

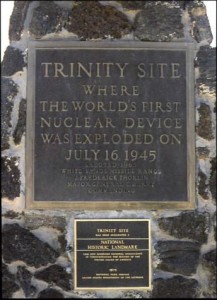

The first Trinity test of an atomic bomb in 1945 yielded an explosion equivalent to 20 kilotons of TNT. Barely seven years later, on November 1, 1952, the United States exploded the first thermonuclear bomb — known colloquially as the “hydrogen bomb” — on Enewetak Atoll, a member of the Marshall Islands group. That first hydrogen bomb yielded an explosion worthy of 10.4 megatons of TNT, 520 times the force of the Trinity blast. Moore’s Law’s got nothing on the early days of atomic-bomb development.

President Truman had likened the Trinity bomb to the wrath of the God of the Old Testament, comparing it to “the fire destruction prophesied in the Euphrates Valley Era, after Noah and his fabulous Ark.” What then to make of the hydrogen bomb? It was a destructive force beyond comprehension. That we got there so quickly was almost entirely down to the drive of one man who was there at the meeting that would lead to the Manhattan Project and the first atomic bomb and who would continue to be a major voice in both American politics and American weapons development through the entirety of the Cold War. Driven by scientific genius, patriotism, paranoia, and a titanic ego, he became the nation’s longest-serving Cold Warrior, perhaps the ultimate exemplar of the mentality that spawned and fueled that shadowy conflict and the lurking specter of nuclear apocalypse that accompanied it. His name was Edward Teller.

Born on January 15, 1908, in Budapest as the son of a prosperous Jewish attorney, Teller didn’t say a word until age three, leading his parents to believe he might be retarded. But then, when he did start to speak at last, he spoke in complete sentences. As a young boy his favorite author was Jules Verne: “His words carried me into an exciting world. The possibilities of man’s improvement seemed unlimited. The achievements of science were fantastic, and they were good.” But he wouldn’t be allowed much time for boyish dreams. During 1918 and 1919, amidst the end of the First World War, the breakup of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Russian Revolution that was taking place nearby, governments came and went quickly in Budapest. First there was the relatively benign if chaotic Hungarian Democratic Republic. Then came the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the second communist state in the world, built on Lenin’s model; it was less benign, and even more chaotic. And finally there was the proto-fascistic Kingdom of Hungary, accompanied by the White Terror, a series of bloody purges and brutal repressions aimed at scourging the country of communism and, it often seemed, the Jews who had disproportionately supported it. The institutionalized discrimination of the period may have been the source of the relentless competitive drive that would mark the rest of Teller’s life; his father told him that as a Jew “he would have to excel the average just to stay even.” His father also told him that he would have to emigrate if he wished to really make something of himself. Young Edward therefore worked like mad on his academics, and in 1926 he was accepted to study Chemical Engineering at Karlsruhe University in Germany.

As the political climate in Germany darkened, Teller completed his undergraduate studies at Karlsruhe, followed by a PhD in Physics at the University of Leipzig. He also lost most of his right foot in a streetcar accident in Munich; he would wear a prosthetic, and walk with a pronounced limp, for the rest of his life. He took up a research post at the University of Göttingen, where he published papers like mad. Setting a pattern that would hold throughout his career, he almost always worked with a coauthor, who would be responsible for sorting insights that sometimes came off more as feverish ravings than rigorous science into some manageable, organized form, and who would do the tedious but necessary work of calculating and verifying what seemed to come to Teller unbidden as intuitive truths. Teller was given to occasional fits of brooding, but at other times could be great fun, possessed of an easy, self-deprecating humor and a ready laugh. He was quite an accomplished classical pianist, but his approach to the art said much about an internal drive that he sometimes masked in casual contact with his peers: he played everything fortissimo, treating the composers whose works he played like personal challengers. On the whole, though, he was well-liked, and increasingly well-respected for his theoretical élan.

But soon it was, as Teller later put it, “a foregone conclusion I had to leave” Germany; Hitler had come to power, bringing with him an institutionalized antisemitism that would soon make his run-ins with bigotry in Hungary seem mild. Thankfully, in 1934 his burgeoning reputation won him an appointment to work with the great Danish physicist Niels Bohr at the University of Copenhagen, the very center of the universe of physics at that time. This was followed by a brief stay at University College London. The following year he accepted a professorship at George Washington University. In the company of his new wife, his childhood sweetheart Mici whom he had returned to Budapest one last time to marry, he booked passage to the United States, not at all sure about his decision to leave Europe. His worries were unfounded; he quickly fell in love with the New World with all the patriotic passion an immigrant often musters, and never again wanted to live anywhere else.

In early 1939 a wave of excitement swept an international physics community still struggling to retain its dedication to the open sharing of knowledge in the face of the war clouds gathering over Europe. Two German scientists, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, had managed a feat most of their colleagues had heretofore considered impossible: they had split an atom of uranium. They had, in other words, achieved nuclear fission. This opened up a possibility that had been long discussed but also long dismissed by most physicists as a fantasy: to create a fission chain reaction capable of releasing almost inconceivable amounts of energy — energy with the potential to create an almost inconceivably powerful bomb. Teller’s fellow physicist and Hungarian émigré Leó Szilárd immediately began agitating for a top-secret crash program to build one of these “atomic bombs,” or failing that to prove definitively that it could not be done. Using logic that would become all too familiar over the decades of atomic history to come, he said that the democratic world had to have the bomb before Nazi Germany. And, having split the atom first, the Germans were obviously already ahead. (Szilárd apparently didn’t consider that the willingness of Hahn and Strassmann to publish their work in scientific journals probably meant that they weren’t, at least yet, thinking all that seriously about its potential as a weapon.) But other scientists, including Bohr, remained unwilling to sacrifice their traditional openness in the name of something which they thought was likely to be impossible anyway. The chief stumbling block was the need for comparatively huge quantities of uranium-235, which no one knew how to produce in any remotely efficient way. “It can never be done,” said Bohr, “unless you turn the United States into one huge factory.” Unconvinced, Szilárd kept insisting that everything had changed as soon as fission was proved to be possible, and that his colleagues denied it at their peril.

It’s at this point that Teller, heretofore a promising but hardly a major physicist, enters the history books for the first time — not as a great thinker in his own right but, as he himself would later dryly put it, as “Szilárd’s chauffeur.” Szilárd didn’t drive, and he needed to get out to Long Island for the second of two meetings with Albert Einstein, now also living in exile in the United States, that would change the course of history. Einstein was just about the only physicist American politicians were likely to be familiar with, the only one they were likely to listen to if he came to them with outlandish science-fictional hopes and fears of a futuristic “atomic bomb.” Thus, barely a month before Germany invaded Poland to touch off the Second World War, Szilárd, Teller, and Einstein sat in the latter’s comfortable sitting room — Einstein still in his slippers — sipping tea. Teller, having already served as chauffeur, now accepted the further indignity of being the secretary, writing down the letter to President Roosevelt that his two older colleagues dictated to him. Hand-delivered to Roosevelt by Alexander Sachs, a well-connected Jewish banker, the letter led to the formation of an “Advisory Committee on Uranium,” forefather of the Manhattan Project, in October of 1939. The Committee included both Szilárd and Teller amongst its members. It was in fact Teller himself who made the first request for funding: for $6000 to finance some early experiments to be conducted by the exiled Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. After considerable argument about the expense, the request was approved.

Still, progress was slow, the government’s support was halfhearted, and even Teller himself was uncertain that he wanted to abandon pure science for weapons research. Then came the German invasion of France and the Low Countries in May of 1940. Teller later claimed that the shocking success of the Wehrmacht convinced him that “Hitler would conquer the world unless a miracle happened.” A speech by Roosevelt galvanized him to action: “If the scientists in the free countries will not make weapons to defend the freedom of their countries, then freedom will be lost.” Teller’s duty as he saw it was clear: “My mind was made up, and it has not changed since.” Actually, records of Roosevelt’s speeches from the period reveal no such formulation as the one in Teller’s recollection. There’s merely an offering of absolution to scientists for having enabled so many technologies which Germany was now putting to such evil use, along with a paean to the search for knowledge, scientific and otherwise, which Germany was now so actively repressing. Nevertheless, Teller would soon believe the “miracle” the world so urgently needed to be within sight in the form of the atomic bomb. His insistence on seeing weapons of mass destruction in such quasi-religious terms would come to define the role he would play in many dramas to come.

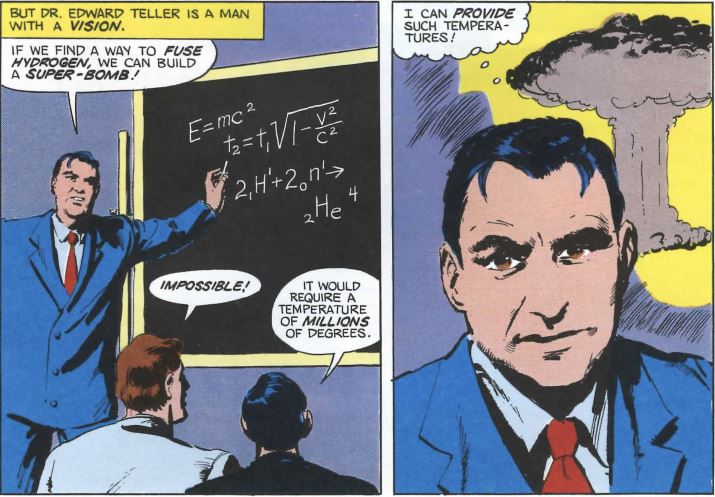

In mid-1941, just a few months after he and Mici took the oath of American citizenship, Edward Teller moved to Columbia to work more closely with Fermi and Szilárd, to whose cause he was now a complete convert. Soon after, he was party to yet another conversation that would change the world, this time with he himself as the active agent of that change. When Teller and Fermi were walking back from lunch one day, the latter mused “out of the blue” whether it might be possible to use the as-yet nonexistent atomic bomb as a mere catalyst for a much bigger bomb, one that fused rather than split atoms. Specifically, hydrogen might be fused to helium, like the process that powered the Sun. Fermi estimated that a fusion bomb could be made to explode with three orders of magnitude more force than a simple fission device. He considered the idea a throwaway; the numbers would start to get so big that you kind of had to ask what the point would really be. Teller, however, took it as a challenge.

This was vintage Teller. Already in 1941 he considered the fission bomb essentially a solved problem in theoretical physics. Just as he needed patient collaborators to clean up and finish his research papers, he was more than happy to turn over the practical work on the fission bomb to others while he swam after the next big fish. Within a year he thought he knew “precisely how to do it.” He broke the news to his colleague and best friend, exiled German physicist Hans Bethe:

Teller told me that the fission bomb was all well and good and, essentially, was now a sure thing. In reality, the work had hardly begun. Teller likes to jump to conclusions. He said that what we really should think about was the possibility of igniting deuterium [an isotope of hydrogen, sometimes known as “heavy hydrogen”] by a fission weapon — the hydrogen bomb.

Teller’s idea was soon christened “the Super.” He estimated that it should be able to “devastate an area of more than 100 square miles.”

Teller followed Fermi to the University of Chicago in 1942, where Fermi took charge of the project to build what became known as Chicago Pile 1, the world’s first nuclear reactor. When activated in November of that year, it proved once and for all that an atomic chain reaction, and thus an atomic bomb, was possible. With that proof, the newly christened Manhattan Project now ramped up in earnest under the stewardship of Army Air Force General Leslie Groves, who was placed in charge of infrastructure and practical and military concerns, and American physicist Robert Oppenheimer, who headed the scientific research. Teller was one of the first scientists to arrive at Los Alamos, the little community Groves and Oppenheimer constructed to finish the work of making the atomic bomb way out in the splendid isolation of the New Mexico desert. Teller liked and admired Oppenheimer with an enthusiasm that could sometimes verge on hero worship. Oppenheimer was, he said, a “bricklayer,” capable of seeing the whole puzzle and fitting its pieces together, as opposed to the “brick makers” around him who could only see their own small piece.

By now the Manhattan Project was working to develop not one but two types of fission bomb. The first would be a relatively crude device that used uranium-235. Niels Bohr’s words about “turning the United States into one huge factory” were proving to be prophetic, as Groves oversaw a massive industrial effort to enrich enough uranium to power it; this part of the Manhattan Project alone would eventually employ tens of thousands of people. The other bomb was a more elegant and efficient but also much more uncertain design that used the newly synthesized element of plutonium instead of uranium. It would have to be triggered by precisely placed and shaped explosive charges, which would implode its plutonium core into a supercritical mass and start the chain reaction. Teller worked for some time on this implosion process, the trickiest technical problem of all those that the Manhattan Project had to overcome.

Teller, however, soon became aggrieving and aggrieved, building the foundation of yet another lifelong reputation: that of someone who just doesn’t play well with others. As the little community of Los Alamos grew around him, Teller had expected to either be placed in charge of all theoretical physicists or of an entirely new project to work on the Super. He didn’t get either appointment. Instead, his old friend Hans Bethe took charge of the theoretical physicists, leaving Teller so resentful that it spoiled their friendship forever. The Super project, meanwhile, never got started at all; it was declared an idea maybe worth revisiting after the fission bombs were finished, but nothing to use resources on now. Teller began to neglect his assigned tasks in favor of working independently on the Super. Bethe, he recalls, “wanted me to work on calculational details at which I am not particularly good, while I wanted to continue not only on the hydrogen bomb, but on other novel subjects.” George Gamow, a Russian émigré physicist who had known Teller from his years in Germany, notes that “something changed” in Teller after he got to Los Alamos. Before, he had been “helpful, willing and able to work on other people’s ideas without insisting on everything having to be his own.” Now… well, not so much. “Since the theoretical division was very shorthanded,” says Bethe, “it was necessary to bring in new scientists to do the work that Teller declined to do.”

Teller took to prowling about distracting scientists from other, more immediately useful work with his ideas and proposals, driving Bethe crazy. At last in the spring of 1944 Bethe, with Oppenheimer’s approval, relieved Teller “of further responsibility for work on the wartime development of the atomic bomb.” (The man who replaced Teller on the implosion team, Rudolf Peierls, brought with him an assistant named Klaus Fuchs who would share many details of the atomic bomb’s design — most importantly the tricky implosion process itself — with the Soviet Union.) Oppenheimer personally convinced an irate Teller not to leave. After all, he said, this was just what he wanted; now he could work on the Super full-time. And so Teller’s work on those first atomic bombs was largely done.

After the war was ended by the dropping of two examples of Los Alamos’s handiwork — one of uranium, the other of plutonium — on Japan, the little desert community began to disperse. Many of the most important minds behind the bomb, including Bethe, Fermi, and Oppenheimer himself, were eager to put weapons development behind them and return to either pure research or, in Oppenheimer’s case, increasing political engagement with the handling of their creation. Teller was deeply disturbed at this loss of brainpower, and even more disturbed that he still couldn’t get approval of his Super project. He wrote an urgent letter trying to convince his colleagues of the necessity of further weapons development, particularly on the Super, which he said was realizable within five years if they all put their minds to it. Deploying the same paranoid logic that had led to the development of the fission bombs, he said that the Soviet Union might very well be able to make a hydrogen bomb without even bothering with a fission-only bomb; the shadowy threat was now the Soviet Union rather than Nazi Germany, but the formulation was otherwise the same. He pronounced colleagues like Oppenheimer who would prefer to reach diplomatic accommodation with the Soviet Union, accommodation which might even entail sharing the atomic bomb with them, guilty of “fallacy.” And, sounding another thoroughgoing theme of his career, he pronounced thermonuclear explosions to be potentially useful for many peaceful purposes; they would “allow us to extend our power over natural phenomena far beyond anything we can at present imagine.”

Some of his colleagues were able to secure time on the ENIAC, by some reckonings the world’s first real computer, to do calculations which seemed to prove the Super feasible. An official conference held at Los Alamos in April of 1946 produced more general agreement that it should be possible, although by no means did everyone agree with all of Teller’s most optimistic predictions for its timetable. For the time being, though, those remaining at Los Alamos were busy preparing for Operation Crossroads, as well as improving the safety and reliability of the existing arsenal. Thus the Super remained firmly on the back burner. Teller himself had already departed in frustration by the time of the Super conference; he joined Fermi at the University of Chicago in February of 1946.

But thirty months later Teller, proclaiming himself increasingly disturbed by the Chinese Civil War and the by now blatant takeover of all of Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union, returned to Los Alamos. “I fully realize the menacing international situation,” he said, “and I believe that the United States must develop its military strength to the utmost if we are not to succumb to the danger of communism.” And, casting himself as a martyr to the cause, he proclaimed a sense of patriotic duty to be behind the move, “in spite of the fact that I cannot hope to work as happily and with as much immediate satisfaction in a field of applied science.” More quietly but perhaps more honestly, he admitted to a friend that it was “quite clear that I am needed in Los Alamos more than I am needed in Chicago,” and “being necessary is an extremely important thing for me.” For their part, many of his colleagues noted not so much a considered position behind his decision as a visceral hatred of the Soviet Union that could sometimes seem to verge on the ethnic. The Soviet Union had just completed its takeover of Hungary in June of 1948, when the Soviet-backed Hungarian Communist Party effectively outlawed the democratic opposition and cut Teller off from his remaining family in Budapest. His Hungarian friend and Los Alamos colleague John von Neumann notes that “Russia was traditionally the enemy” of Hungary, subject to “an emotional fear and dislike” among his countrypeople.

Teller’s return to Los Alamos coincided with increasingly urgent consideration of the Super in the halls of government, prompted by clear signs from intelligence sources that the Soviet Union was getting close to a fission bomb of its own. “It would be dreadful,” wrote a White House aide named William Golden, “if the Russians got it [the Super] first.” Teller was on holiday in England in September of 1949 when he got the news that the Soviet Union had just exploded its first atomic bomb, at least a year before the CIA’s most pessimistic predictions.

His advocacy now shifted into overdrive. Despite the fact that the Soviets were still very obviously playing catch-up, and largely using stolen American designs to do so (that first Soviet bomb was a virtual clone of the Trinity bomb), he announced that the United States was in “grave danger that we have lost or are losing the atomic armaments race.” “If the Russians demonstrate a Super before we possess one,” he declared, “our situation will be hopeless.” His logic was questionable at best, to the extent that Yet he had at last an eager audience looking for any source of comfort in the face of the Soviet test. Oppenheimer, now increasingly at odds with Teller personally as well as professionally, wrote despairingly of “this miserable thing” that “appears to have caught the imagination, both of the Congressional and of the military people, as the answer to the problem posed by the Russian advance.” Seeing it as “the way to save the country and the peace,” he wrote, “appears to me full of dangers.” Teller took very, very personally Oppenheimer’s advocacy for diplomacy with the Soviet Union and his persistent skepticism about both the moral wisdom and the technical feasibility of the Super.

Advocates of reasoned diplomacy seldom won over advocates of nuclear armaments during the Cold War. On January 31, 1950, President Truman announced to the world that the United States was going forward with work “on all forms of atomic weapons, including the so-called hydrogen or super-bomb.” Announcing the Super publicly in this way made a marked contrast to the top-secret Manhattan Project. The move, driven largely by domestic political calculations on the part of Truman’s staff, explicitly defined future nuclear research as a race to the Super between the Americans and the Soviets, a sort of perverted forefather to the Moon Race in which both sides would seek to be first to unleash the most terrible destructive force in the history of humanity.

Some scientists declined to work on the project out of moral misgivings; others simply because they didn’t want to work with Teller. Future Nobel laureate Emilio Segrè, for example, pronounced Teller “dominated by irresistible passions much stronger than even his powerful rational intellect,” and turned his job offer down. The core of the team that was finally assembled included, in addition to Teller, two less visible European veterans of the Manhattan Project, Stanislaw Ulam and John von Neumann. They didn’t make for a very happy family. Within weeks Ulam was complaining about “Edward’s obstinacy, his single-mindedness, and his overwhelming ambition.” As Ulam and Neumann worked through the sorts of tedious calculations that Teller always found beneath him, a painful reality slowly dawned on them: Teller’s plan for the Super, which he had first conceived even before the fission bomb was a reality, simply wouldn’t work. When they tried to demonstrate this to Teller, the latter, in the words of Stanislaw Ulam’s wife Françoise, “objected loudly and cajoled everyone around into disbelieving the results. What should have been the common examination of difficult problems became an unpleasant confrontation.” “Teller was not easily reconciled to our results,” says Stanislaw Ulam himself more laconically. “I learned that the bad news drove him once to tears of frustration, and he suffered great disappointment. I never saw him personally in that condition, but he certainly appeared glum in those days, and so were other enthusiasts of the H-bomb project.” Teller was soon engaging in conspiracy theorizing, believing that Ulam and von Neumann were deliberately biasing their findings to make him and his Super look bad. He demanded that virtually all of Los Alamos be placed at his disposal, but as 1950 ground on and his theories looked more and more flawed nobody, least of all Teller, seemed quite sure what they should actually be doing.

Then, one day in late January of 1951, Françoise Ulam found her husband staring vacantly into their back garden. “‘I found a way to make it work.’ ‘What work?’ I asked. ‘The Super,’ he replied. ‘It is a totally different scheme, and it will change the course of history.'” The technical details of Ulam’s new scheme, and of Teller’s original, we won’t go into here. Suffice to say that Teller immediately saw the new idea’s potential. “Edward is full of enthusiasm about these possibilities,” wrote Ulam to a colleague. In an indication of just how far their relationship had deteriorated, he then added a stinger: “This is perhaps an indication they will not work.”

There soon followed what

From then on Teller pushed Stan aside and refused to deal with him any longer. He never met or talked meaningfully with Stan ever again. Stan was, I felt, more wounded than he knew by this unfriendly reception, although I never heard him express ill feelings toward Teller. (He rather pitied him instead.) Secure in his own mind that his input had been useful, he withdrew.

Teller would minimize Ulam’s contribution for the rest of his life. Ulam himself never seriously campaigned to be awarded his own proper share of the credit, perhaps because he was much more ambivalent about their accomplishment than Teller. He often compared the hydrogen bomb to the Jewish legend of the Golem, which, having been created as a means of protection, eventually gets out of its maker’s control and goes on a murderous rampage through Prague.

With the Super now looking feasible, the Korean War raging, and the knowledge that, thanks not least to Truman’s grand pronouncement, this was now a race with the Soviets, even the likes of Oppenheimer, Fermi, and Bethe now supported its development. Teller, however, still created chaos everywhere he went. He demanded to be placed in sole charge of the Super project, including not only the research but the logistics, the engineering, and the administration. Knowing that that way lay madness, Los Alamos director Norris Bradbury absolutely refused. On September 17, 1951, Teller quit in a huff. Many of his colleagues mumbled darkly about what seemed a developing pattern: Teller had quit on the fission-bomb project as well just when it needed him most. (Teller himself would likely have replied that, as a theoretical physicist through and through, he was neither terribly interested in nor terribly good at the engineering details of actually building either the fission bomb or the Super.) “Once Teller left Los Alamos,” Bethe remembers, “even though they were working on ‘his’ weapon, he found all sorts of reasons why it wouldn’t work. He tried to criticize it wherever possible.”

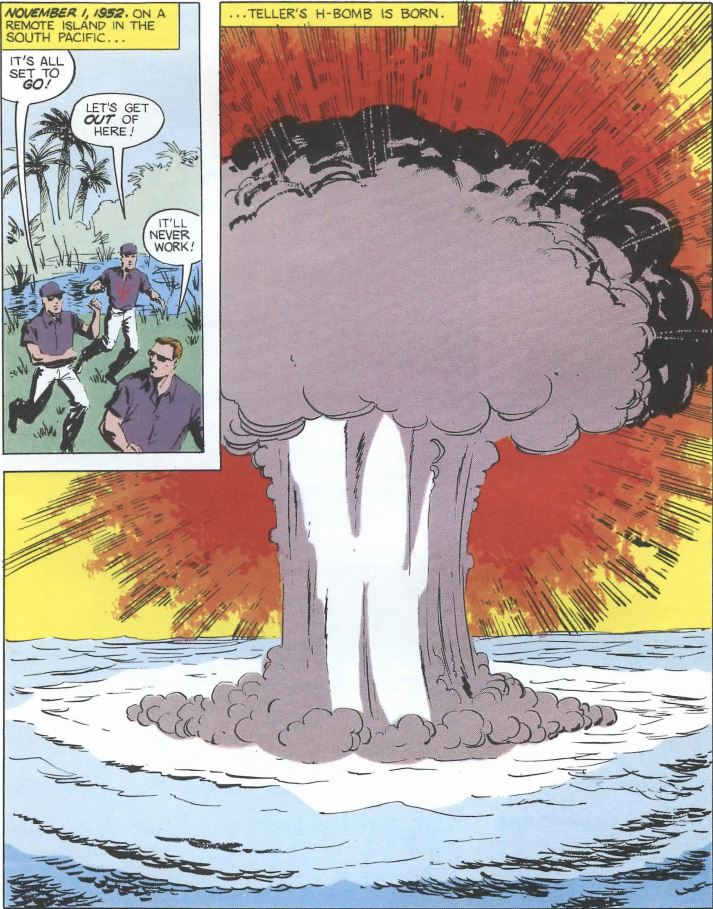

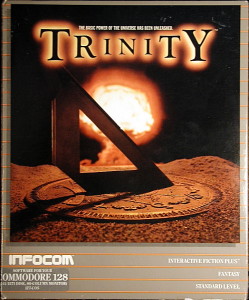

Nevertheless, Los Alamos soldiered on to shock the world and escalate the nuclear standoff to a potentially planet-wrecking scale when they detonated the first hydrogen bomb on November 1, 1952, a scene evocatively portrayed by Trinity in the vignette whose extracts open this article. It stripped not only Enewetak but every nearby island of all animal life and vegetation, as if someone had taken a giant potato peeler to their surfaces. It blew 80 million tons of highly radioactive material high into the air; parts of the fallout would travel to every corner of the globe. It vaporized birds in midair. It cooked nearby fish as if they had been dropped into a hot frying pan. (Yes, that cute, friendly dolphin that was so helpful to you in Trinity wasn’t long for this world.) Teller’s dubious dream had come to its fruition.

He should have been pleased, but he had other things on his mind. While Los Alamos worked to finish the Super, he was organizing an entirely new nuclear-weapons laboratory that would not be bound by what he saw as the carping pessimism of Los Alamos. The Radiation Laboratory at Livermore was founded on the site of a mothballed naval air station in Livermore, California, that summer of 1952. Teller claimed to be too busy setting it up to make the trip to Enewetak to witness the blast, but most of his old colleagues attributed his failure to appear to pique; they believed he had been secretly hoping to see them fail, so his new laboratory could sweep in and save the day. This alleged disappointment did not, however, keep him from claiming his paternity. “It’s a boy!” he announced.

On August 12, 1953, when the Soviet Union exploded its own inevitable first hydrogen bomb, the die for 35 more years of mutually assured destruction was irretrievably cast. On October 30, 1961, almost exactly twenty years after the idle lunch-time conversation that had spawned it, Teller’s baby reached terrifying adulthood when the Soviets detonated over the remote archipelago of Novaya Zemlya the largest atomic bomb and the largest force of any sort ever triggered by humans, a 50-plus-megaton thermonuclear monster that was promptly dubbed the “Tsar Bomba.” It produced a mushroom cloud over seven times the height of Mount Everest; would have caused third-degree burns to someone standing 60 miles away; broke windows over 500 miles away. Even by the standards of the institutionalized insanity of the Cold War this was madness. Neither the Soviets nor the Americans ever tested or built another bomb of anywhere close to that size for the simple reason that no one could quite imagine what to actually do with such a giant. Their 5- and 10-megaton warheads were less expensive, easier to make, and had more than enough megatonnage among them to destroy all life on the planet.

By the time of the Tsar Bomba Teller had largely abandoned the nuts and bolts of nuclear physics in favor of a career as an administrator of the military-industrial complex and as an increasingly visible political advocate for nuclear weapons and the strongest possible anti-communist stance. Just as Los Alamos seemed to have inherited some of its founder Robert Oppenheimer’s personality, being relatively cautious and pragmatic about the terrible weapons it developed, Teller’s Livermore laboratory developed a reputation for shooting from the hip and a damn-the-consequences drive for ever bigger and dirtier bombs. Teller characterized his transformation from physicist to advocate as a principled move that he made only sadly and reluctantly. He was, he claimed again, a martyr to his thankless cause: “I cannot just go back to physics because I believe that to prevent another war happens to be incomparably more important.” Others questioned whether Teller didn’t enjoy the limelight a lot more than he admitted. Robert Brownlee, a colleague who worked with him during the 1950s, makes this observation:

Edward was, in my experience, two entirely different people. When he was with scientists, just scientists, every idea was interesting and valuable and rational and so on. And the moment a certain kind of person would walk in the room, a person who was outside the family, and therefore might take tales back, a press person, Edward would become a wild man. He would be showing off for the press or for the visitor, would say things that would make you do this: This guy has absolutely lost it, he’s completely crazy. But it was an affectation which he put on when somebody came. So the press, whenever they interviewed him, carried away with them a strange view of Edward. When he was just with us kids, he was not that at all. So when you could talk with Edward with the people right there, it was entirely different than having a stranger in there, because the moment that stranger arrived, Edward became another person. And it had something to do with publicity—I don’t know a better word for it. There must be a better word for it. But I learned that despite what everybody else at the lab said, Edward’s value had to be determined independent of his personality. He was extremely valuable, but nobody liked him because he was, every so often, totally flaky.

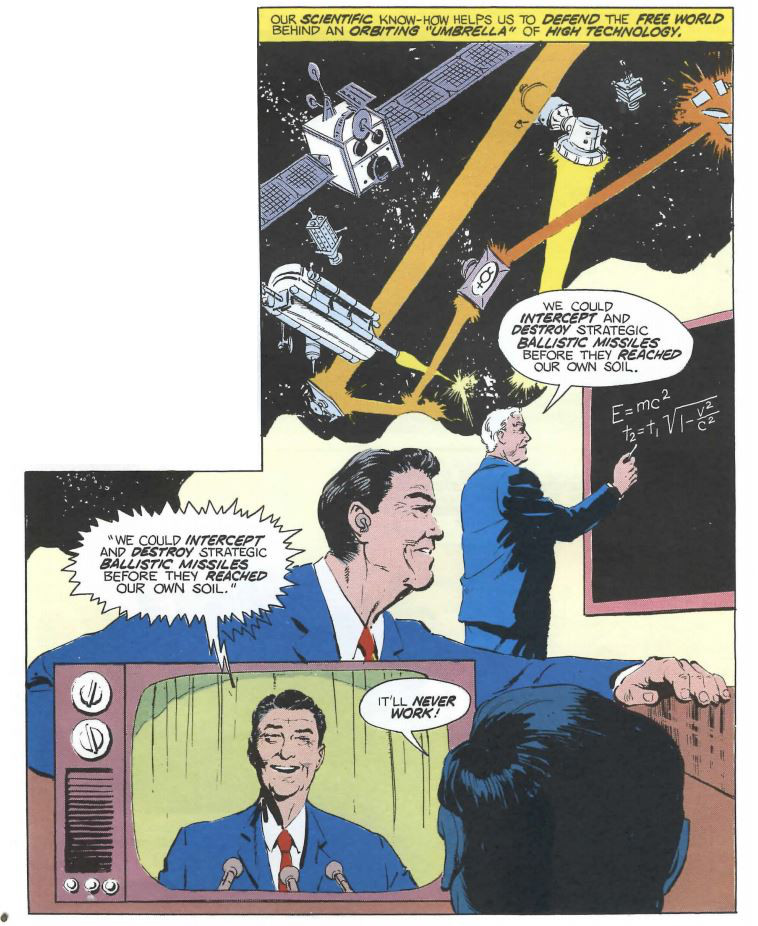

It was apparently this “crazy” version of Teller that the American people at large came to know well by 1960. After Teller made headlines across the country through his strident opposition to the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963 that moved all nuclear testing underground, Stanley Kubrick was inspired to make his caricature the eponymous star of Dr. Strangelove. He became for decades the favorite scientist of the American Right largely by telling them exactly what they wanted to hear. For instance, he played a major role, as we’ve already seen, in Ronald Reagan’s foolish SDI initiative of the 1980s, claiming to be able to provide not only its technology but also providing its justification: “If we went into a nuclear war today,” he said in 1980, “there is practically no question that the Russians would win that war and the United States would not exist.” The similarity of this rhetoric to that he had used to justify the Super 30 years before is not, I trust, lost on you. Even as the technologies of warheads and delivery systems evolved, the arguments employed in their justification always had this weird fly-in-amber consistency about them, leaving one to wonder when, if ever, enough would finally be enough. If anything, Teller’s rhetoric grew more extreme over the years; he once claimed that the United States had fallen so far behind the Soviet Union that he fully expected to be in a Soviet prisoner-of-war camp — if not dead — within five years. His unapologetic advocacy of nuclear weapons and nuclear power continued until his death at age 95 in 2003. After the Cold War ended, rather than being thrilled at having seemingly achieved the goal he had worked toward for so many years, he merely chose a new bogeyman to fear: Saddam Hussein.

Teller had by then been ostracized for decades from his old Manhattan Project colleagues, who, whilst Teller plunged into Cold War politics, had collected an impressive shelf of Nobel Prizes amongst themselves working with more peaceful applications of nuclear physics. He replaced those old relationships with new ones forged with a group of younger colleagues at the Livermore laboratory who, having had their educations largely funded by the military-industrial complex, saw themselves first and foremost not as scientists but as weapons designers. To them, Teller was a hero. To the old guard, he was nothing less than the traitor in their ranks. The source of their enduring enmity was not his questionable advocacy for the Super or even his slighting of Ulam, but rather another sequence of events involving a man he had once admired greatly: Robert Oppenheimer.

In May of 1952, the FBI questioned Teller on the subject of Oppenheimer, another in a seemingly endless string of pseudo-investigations born of Oppenheimer’s pre-war involvement with communist causes and his current less than gung-ho attitude toward the nation’s nuclear buildup. Teller, who believed Oppenheimer personally responsible for delaying his beloved Super program, laid into his old boss with a vengeance. The country, he claimed, could easily have had the hydrogen bomb a year ago if not for Oppenheimer’s obstructionism. While he stopped short of outright calling him a Soviet spy, he was careful not to exclude the possibility either. Otherwise, he conducted what amounted to a character assassination. Oppenheimer was motivated not by principle but by vanity and jealousy in his opposition to Teller’s plans, as he didn’t want to see Teller better his own fission bomb with the Super. He had “great ambitions in science and realizes that he is not as great a physicist as he would like to be.” (Ironically, many of Teller’s colleagues would have happily accused him of this exact deep-seated sense of insecurity and its resulting personal failings.) It would be better for the country, Teller said, if Oppenheimer was “separated” from the corridors of power.

Not quite two years later, with Joseph McCarthy’s communist witch hunt near its peak, Oppenheimer’s enemies pounced openly at last, initiating hearings to revoke all of Oppenheimer’s security clearances; doing so would end his time as a policy adviser since virtually all of the policy about which he advised involved classified weapons systems. In April of 1954, Robert Oppenheimer was effectively put on trial. A parade of hawks from inside the military, the FBI, and the Washington establishment testified against him; a parade of his old Manhattan Project colleagues testified strongly in his favor. Except for Edward Teller. Called to the stand on April 28, Teller was unwilling to support Oppenheimer but also seemingly too craven to repeat his accusations of two years before in the man’s presence. Asked point-blank if he believed Oppenheimer a security risk, he equivocated like mad:

In a great number of cases I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer acting — I understood that Dr. Oppenheimer acted — in a way which for me was exceedingly hard to understand. I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated. To this extent I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more. In this very limited sense I would like to express a feeling that I would feel personally more secure if public matters would rest in other hands.

I believe, and that is merely a question of belief and there is no expertness, no real information behind it, that Dr. Oppenheimer’s character is such that he would not knowingly and willingly do anything that is designed to endanger the safety of this country. To the extent, therefore, that your question is directed toward intent, I would say I do not see any reason to deny clearance.

If it is a question of wisdom and judgment, as demonstrated by actions since 1945, then I would say one would.

“I’m sorry,” said Teller to Oppenheimer as he left the courtroom. “After what you’ve just said, I don’t know what you mean,” replied Oppenheimer. On May 27, Oppenheimer’s security clearances were formally and permanently revoked. “I think it broke his spirit really,” says an old friend. “He was not the same person afterward,” says Bethe. He spent most of his remaining years sailing and puttering around his beach house in the Virgin Islands. The Kennedy and Johnson administrations made some efforts to rehabilitate his reputation, most notably awarding him the Enrico Fermi Award for his service in 1963, but his security clearances, and with them his political influence, were never restored. He died at age 62 in 1967.

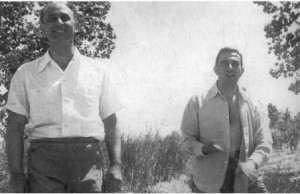

Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Teller share an uncomfortable handshake on the occasion of the former being awarded the Enrico Fermi Award, 1963.

After the trial was done and gone, the scientists who had once worked with and admired Teller were left with the same question that we are: what the hell happened to him? How did this brilliant young scientist turn into the paranoid war-monger Americans soon got used to seeing on their television screens, opposing in his thickly accented English every effort at arms control ever mooted during the Cold War? How could a nuclear physicist, raised on science, talk about winning nuclear wars and dismiss the dangers of radioactive fallout as trivial?

There have been thousands of theories deployed in thousands of attempts to figure out Teller. Some have pointed back to that Munich street-car accident in his youth, which they claim — a bit melodramatically in my view — left him “in constant pain” for the rest of his life. Some have noted his deep-seated personal insecurity, which seemed to have its origins even earlier, to when he as a sheltered child with a doting mother suffered constant abuse and harassment at school for the crimes of being smart and being Jewish. Some have traced his hatred of communism to the chaos it brought to the Hungary of his youth — or, as noted previously, traced it to a Hungarian’s ethnic antipathy for Russia and the Russians. Enrico Fermi’s observation is amongst the most telling as well as the most witty: Teller was the only monomaniac he knew, he said, who had several manias.

Whatever made Teller the man he became, it wasn’t as simplistic as any of the above, taken in isolation or even in combination. For all his legendary arrogance and his willingness to hold grudges, he was also frequently described as a “warm” man and a good, true friend. When his former colleagues all cut him after his testimony at Oppenheimer’s security hearing, sometimes even publicly refusing to shake his hand, Teller reportedly spent hours “weeping” at the spoiling of most of the most important relationships in his life. He even tried desperately to recant his testimony, only to learn it was too late. No, none of us humans are that easy to figure out.

Yet there does seem to be a larger pattern that holds true not only for Teller but for many other architects of the nuclear-arms race: the sheer seductive allure of the Bomb itself. As Trinity‘s box copy proclaims, “The basic power of the universe has been unleashed.” To wield such unprecedented power is a heady drug indeed. The Bomb is the One Ring, the Dark Side of the Force. (Interesting that so many of the most enduring mythic fictions of the Cold War feature such powerful but corrupting temptations…) Some people, like Robert Oppenheimer, were Prosperos, unnerved by its power and eager to eliminate it from the world. Others, like Edward Teller, were Dr. Faustuses, ready to ride this unholy force right down to the depths of Hell. Dueling aphorisms coined by the two men sound like extracts from Paradise Lost. “Physicists have known sin,” says Oppenheimer, eyes downcast. Teller, his trademark bushy eyebrows twitching with passion, replies, “Physicists have known power!”

(For a good history of the relationship between Teller and Oppenheimer — and also Ernest Lawrence, a figure I didn’t have room for in this article — see Brotherhood of the Bomb by Gregg Herken. You can find Carl Sagan’s article on Teller in The Demon-Haunted World.)