Peter J. Favaro started blending computers with psychology some eight years before Activision published his groundbreaking “life simulator” Alter Ego. In his first year as a graduate student of Clinical Psychology at Long Island’s Hofstra University, he and another student developed an obsession with the early standup arcade game Space Wars (a direct descendent of that granddaddy of all arcade games, MIT’s Space War).

During one of the many psychological discussions which developed around those sessions, I wondered whether the games served some kind of therapeutic function for us. They took us away from the pressure of graduate school for a short time and gave us a chance to act out some of our competitive urges. I also wondered what kinds of motor and reflex skills the games were training in us. One of the last things we said about video games that day was that they would be fun to study in some small research projects.

Games and the mostly young people who played them would come to dominate Favaro’s years at Hofstra.

As arcades and the Atari VCS grew in popularity over the course of those years, an anti-videogame hysteria grew in response. The Philippines and Singapore banned arcades outright, claiming they “cause aggression, truancy, ‘psychological addictions’ akin to gambling, and encourage stealing money from parents and others to support children’s videogame habits.” Closer to home, the Dallas, Texas, suburb of Mesquite banned children from playing videogames in public without a parent or other adult guardian, prompting a rash of similar bans in small towns across the country that were finally struck down by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional in 1982. Undaunted, Ronald Reagan’s unusually prominent new Surgeon General, C. Everett Koop, waded in soon after, saying videogames created “aberration in childhood behavior” and, toting one of the anti-videogame camp’s two favorite lines of argument, claiming again that they addicted children, “body and soul.” Others colorfully if senselessly described videogames as substitutes for “adolescent masturbatory activity,” without clarifying what that deliciously Freudian phrase was supposed to mean or why we should care if it was true.

Favaro labored to replace such poetic language with actual data derived from actual research. His PhD thesis, which he completed and successfully defended in late 1983, was entitled The Effects of Computer Video Game Play on Mood, Physiological Arousal, and Psychomotor Performance. One of the first studies of its kind, it found that there was nothing uniquely addictive about videogames. While there were indeed a small number of “maladaptive” children who played videogames to the detriment of their scholastic, social, and familial lives, the same was true of many other childhood activities, from eating sweets and chips to playing basketball. With regard to the other popular anti-videogame argument, that they made children “aggressive,” Favaro found that, while violent videogames did slightly increase aggression immediately after being played, they actually did so less than violent television shows. Also discredited was a favorite claim of the pro-videogame camp, that the games improved hand-eye coordination. Favaro found that playing a videogame for a long period of time made children better at playing other videogames, but had little effect on their motor skills or reflexes in the real world. Favaro would remain at Hofstra doing similar work until several years after completing his PhD.

While he was conducting his research, Favaro, an ambitious, personable fellow who had become something of a hacker following his purchase of an Atari 800, fostered links with the computer-industry trade press. After contributing articles to various magazines for some months, he became a “Special Projects Editor” with SoftSide beginning with the January 1983 issue, curating features on education and the relationship of children to computers until that magazine’s demise a year later. He then spent almost two years with Family Computing in largely the same role. He wrote cover-disk programs like Relaax…, which walks you through a series of relaxation exercises, and Pix, which lets you draw pictures by assembling, collage-like, smaller images on the screen. His most notable creation of this period for our purposes is Success, a multi-player Life-like computerized board game that starts by having you choose a personality — “aggressive,” “impulsive,” “pragmatic,” or “romantic” — and a goal in life — “money,” “knowledge and intellectual curiosity,” or “health and happiness.” You then move around the board flipping “cards” that affect your progress in the various goals: a “recent swamp purchase” decreases your money by $150, while a marriage proposal sends you to an arcade-style mini-game that places you behind the wheel trying to get to the church on time. Other ideas that would be incorporated into Alter Ego can be found in his articles on game design. Presaging the innovative character-creation system of Ultima IV as well as Alter Ego, he suggests in SoftSide‘s September 1983 issue quizzing the player of an adventure game about her personality before kicking off the proceedings in earnest:

In a situation where danger was imminent, would you

A) Ask for help.

B) Take charge and take action.

C) Run for your life.

The same article suggests a scoring system based on the player’s “display of bravery, risk-taking, judiciousness, pragmatism, or whatever else you would like to reinforce.”

In an interview he gave in 2007 which contrasts weirdly with the idealistic tone of magazine articles like that one, Favaro claimed he made Alter Ego for very pragmatic reasons: out of his “love for game design and the prospect of making some money,” using his academic background as “a way of breaking out of the pack of other designers.” It’s not clear how rigorous his claimed research for the game — interviews with “hundreds of people” about their “most memorable life experiences” — really was, or whether it was even conducted solely in the service of this project or was a more general part of his ongoing psychological research at Hofstra. What is very clear, however, is that his idea for a “life simulator” was just the sort of high-concept, innovative project that Jim Levy’s Activision 2.0 swooned over. It didn’t take much to convince them to sign the project. Favaro would write and prototype the game on his Macintosh, while Activision would contract the final programming out to two outside developers: Kottwitz & Associates to do the Apple II and MS-DOS versions, and Unimac to do the Macintosh and Commodore 64 versions. Activision loved the cachet bestowed on the project by Favaro’s status as an actual psychologist so much that they always made sure to refer to him in the packaging, the manual, and advertisements only as “Peter J. Favaro, PhD.”

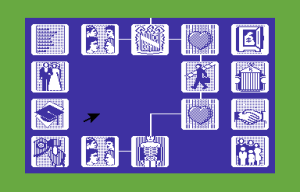

Alter Ego, which comes in a male and a female version, begins with a multiple-choice personality test that sets your initial scores in twelve characteristics that will be tracked throughout the game: Calmness, Confidence, Expressiveness, Familial, Gentleness, Happiness, Intellectual, Physical, Social, Thoughtfulness, Trustworthiness, and Vocational. You then get to live an entire life: the first scene has you in the womb getting ready to make your big exit (or, if you like, entrance), while the last is the scene of your death, at whatever age and in whatever manner your choices and the cruel vagaries of chance cause that to be. The years between are divided into seven distinct phases: Infancy (birth to age 3), Childhood (ages 4 to 12), Adolescence (ages 13 to 17), Young Adulthood (ages 18 to 30), Adulthood (ages 31 to 45), Middle Adulthood (ages 46 to 64), and Old Age (age 65 to death). Each phase plays out as a series of little interactive vignettes, both universal “life experiences” in the form of the track running down the center of the screen and “life choices,” having to do with relationships, marriage and family life, your career and finances, etc., represented by icons to either side of the experience track. Playing Alter Ego is a matter of choosing to have a life experience or to make a life choice by clicking the appropriate icon, then reacting to what follows as you believe you would in real life — or as you believe the character you’ve chosen to play would. The outcome of most vignettes will affect you in some way, whether by changing some of your twelve characteristics or by bringing more concrete changes to your life, like marriage, a new career, the death of somebody close to you, or for that matter your own death. If nothing else, some time will pass and you will age that little bit. (In a ludic illustration of the way time just seems to fly by faster as you get older, time jumps in larger chunks between later episodes as compared to earlier.) Your personality characteristics, relationship and marriage status, income, etc., in turn affect the vignettes themselves — closing some off to you entirely, altering what transpires in others. While there are still plenty of times where the lack of more comprehensive state-tracking can make the episodes feel inappropriate for your you, Alter Ego does its best, and its best is sometimes better than you might expect.

Leaving aside for a moment the larger thematic innovations of Alter Ego, the interface itself is well worth considering. It is, first of all, yet another impressive implementation of a Macintosh-style interface on computers that predate the Mac itself by years. But more important is Activision and Favaro’s decision to not try to make Alter Ego work through a parser. I’ve railed before against games that want to present big, life-changing choices rather than dwelling on the granular minutiae of Zork, but that insist out of misplaced traditionalism on forcing you to make those choices through a parser. Alter Ego, however, at long last shows the courage to break with tradition. Rather than offer only a few options but force you to wrestle with a parser to divine what they are, Alter Ego just shows you your options and lets you choose one. That may seem reasonable and unremarkable enough today, but it makes Alter Ego one of the first computerized hypertext narratives, a forerunner of Storyspace and the many similar systems that followed. I don’t make any claims to absolute firsts for Alter Ego; our old friends Level 9 in Britain among others were also experimenting with choice-based narratives by the mid-1980s. Still, Alter Ego stands as the most prominent early example of the format. Given that a menu of choices is so much easier to implement than a parser and the relatively complicated world model that must lie behind it, one might well wonder what took the industry so long. My suspicion, for what it’s worth, is that developers were consciously or unconsciously concerned about differentiating themselves from the Choose Your Own Adventure books that were all the rage at the time in children’s publishing.

But now it’s time to get beyond mechanical innovations and the brilliantly original concept itself and look at what it’s actually like to play Alter Ego. More so than even a typical text adventure, which has puzzles and other logistical concerns to distract, a game like this lives and dies for me on the quality of its writing. In this department Alter Ego is, at best, a mixed bag. The early vignettes are the most natural and effective — perhaps because Favaro was technically a child psychologist by trade, perhaps because he was only in his late twenties at the time he wrote the game and thus had only his book learning to draw from when describing the later stages of life. I’m afraid I’m going to be pretty hard on old Peter J. Favaro, PhD, soon enough, so let me first offer a couple of childhood episodes that I really like. One might make you laugh, and the other might… well, okay, it’s a bit sentimental and contrived, what with both husband and daughter managing to get themselves killed by the same freight train, but it’s also very sweet. (In the extracts that follow, I’ll be mixing the male and female versions of the game pretty freely.)

You are sitting in a large place, and a furry man walks up to you. He's walking around you in circles.

Select a mood:

curious

frightened X

Select an action:

point at the furry man

make noises at/talk to the furry man X

The furry man walks right up to you and smells you up and down. His nose pokes into your face and neck. It's cold.

Select an action:

cry X

grab the furry man by the head

push him off you

Your mom comes over and says the furry man is just playing. She takes your hand and puts it on the furry man's back and says, "Nice 'doggie'."

Select an action:

pet the man X

stay frightened and go away from the man

See? It isn't that bad. You pound on the man's back and say, "Nice 'doo-gee'."

There is an elderly woman who lives in a house up the street. Everyone calls her "the witch." Some people say she's really paranoid, calling the cops on kids all the time and screaming out the window, even when there is nobody there. At night she keeps her light on all the time and sits looking out the window.

For the past few days the light has been off. Some of the kids think she's just dead in there or something. They jump in front of her house and sing "Ding dong, the witch is dead, the witch is dead," and laugh.

Select a mood:

sad X

happy

Select an action:

sing with everyone else

try to see if anything is wrong X

One afternoon after school, you look from outside the gate to see if there is anything going on inside the house. There is nothing. You can:

go through the gate and knock on the door X

ask a friend to go with you

You hear a voice call out from the back of the house, "Go away and leave me alone!" You can:

say "I'd like to know if you're o.k. in there." X

quit trying and leave

You hear nothing for about 30 seconds. Finally, the door opens. The woman looks pale and dazed. She seems smaller than you imagined and very delicate. In the corner of her almost-bare living room there is a television set; beside it is a large box of old rubber balls and toys that were left, or had accidentally fallen, on her lawn.

She asks you why you have come. You mention that you noticed that the light has gone out, and you thought she might be needing some help. She explains that she has no way to replace it. She is too old to climb up to do it. You can:

ask her if she would like you to do it X

excuse yourself, now that you know it's just a problem with a light bulb

She thanks you. Her face softens. While you are fixing the light, she tells you a very sad story: A long time ago, she had a little girl very much like you, so polite and so kind. She says her daughter was beautiful, and repeats it over and over--"as beautiful as a picture."

She and her husband lived with their daughter not too far from the train yard. She used to tell her child, "Anne Marie, stay away from the tracks, or you'll get hurt." One day, her daughter and her husband went out to play catch with an old ball. The ball got away from Anne and rolled across the tracks.

While she was chasing it, her foot got wedged between two rails. Her father and she struggled to release it, but before they could, they were both struck by a freight train and killed. She's been alone ever since.

When you are finished fixing the light, the lady gives you some milk and freshly-baked cookies. It almost seems as though she doesn't want you to go. Before you leave, you:

thank her for the cookies and ask if she would like someone around to do odd jobs X

thank her and excuse yourself

Her face brightens. "You must be paid," she says. "I can't afford much, and you'll have to do a fine job, but you can have all the cookies and brownies you can eat. I promise you that." You have done a much kinder thing than you can probably imagine at your age. You've given this woman a reason to live.

Many other vignettes unfortunately manifest the clunkier qualities of the one above without the same endearing sweetness.

The subject of sex has inspired far more bad writing over the course of history than any ten other topics combined. For better or for worse there’s lots and lots of sex in Alter Ego, so much so that it obviously made Activision more than a little nervous; there are prominent warnings on the box and in the manual, and when you actually stumble into a vignette with naughty content you get a big warning message so you can quickly back out with your delicate sensibilities undisturbed. (When we played Alter Ego as kids, of course, that warning meant we’d hit pay dirt.) Some of these episodes feel like they’re lifted from a late-night skin flick.

Perri Barber is an acquaintance who has taken a few of the same classes you have. She is a petite brunette with gorgeous green eyes, a nice smile, and a slim athletic body. She approaches you on campus and asks if you would be interested in helping her paint her dormitory room. What will you do?

help her decorate X

pass on the opportunity

During the course of the afternoon, you get to know one another very well. You work together in close quarters (the room is very small), so a lot of accidental touching and bumping occurs during the day. You aren't sure, but you think that Perri is coming on to you.

Select an action:

suggest that the two of you shower off together

ignore any signals that she might be giving you X

I guess this is not your style. It IS Perri's style, though. She asks if you would like her to scrub all that paint off your gorgeous body.

Select an action:

accept the offer X

reject the offer

The two of you take a nice, warm, romantic shower together. I'll leave what comes after the shower up to your imagination. [Thank God for that!]

When not indulging in teenage-boy fantasies, Alter Ego‘s attempts at the risqué manage to be weirdly, anticlimactically square, the sort of things a gaggle of Monty Python housewives would define as transgressive.

Until now, your sexual experiences with your wife have been the standard fare. You've done a little experimenting with positions but that's about it. Have you been thinking about suggesting something a little more out of the ordinary?

"as a matter of fact, yes" X

"no"

What would you like to try?

oral sex X [Shocking!]

being tied up and tickled [No, I couldn't possibly...]

experimenting with marital aids (vibrators, creams, etc.) [Gasp!]

suggesting a menage a' trois (sex with your wife and another woman at the same time) [Now we're getting somewhere... and why do I find the game's need to define this phrase so unaccountably hilarious?]

Your wife is too inhibited to do this, she tells you she would rather not. [Oh, well, it was worth a try...]

In case you were wondering: no, if you play as a woman, you don’t get to ask for sex with two men at once. The woman always gets the short end of the stick in Alter Ego, about which much more in a moment.

Alter Ego is relentlessly hetero-normative. Apart from the ménage à trois, which at least in this context is of course really a heterosexual male fantasy, there are only a couple of places where the game even acknowledges the possibility of alternative sexualities. At one point you can be asked by your French teacher, Mr. Andre, “who everyone in school claims is gay,” to stay after school to help him clean his office. If you ignore the teasing of your classmates and brave the danger, he turns out to not be a Big Scary Gay Man after all: you learn he has a wife and a beautiful daughter, whom he sets you up with to boot. (The game’s blasé assumption that because he has a wife he doesn’t have feelings for men and doesn’t desire you is… interesting.) In another vignette a friend tells you that he believes he is gay, a revelation that the game treats with the same tragic gravity as a terminal disease.

But then, considering the time and place that spawned it, it’s not really fair to expect much more from Alter Ego. It’s very much a product of its time — sometimes depressingly, oppressively so. And, as Adam Cadre once hilariously noted, that time never changes even as a lifetime’s worth of personal experience plays out. Alter Ego‘s milieu is a frozen-in-amber world where a 512 K PC is the best you can buy, where The A-Team and Miami Vice rule the television, where Jordache jeans and Members Only jackets rule in schoolyard fashion, where Madonna is all over MTV (okay, maybe some things really are eternal). Whether you find this horrifying or nostalgically comforting depends on the player I suppose; I lean toward the former personally. Social change — history in general — just doesn’t happen in Alter Ego, which can be as strange to experience as it is understandable from a design perspective: having already tried to create a complete interactive life story, it’s a bit much to expect Favaro to create a believable future history to accompany it, and it likely wouldn’t have turned out very well had he tried. Still, playing Alter Ego is like living your life inside the white-bread confines of a 1980s version of The Truman Show. Literally white: apart from the occasional socially-inept immigrant kid you can choose to feel sorry for, everyone in this game is the whitest shade of pale.

If Alter Ego‘s lack of inclusiveness is to some extent forgivable given its origins, I do have more problems dismissing Favaro’s cluelessly demeaning sexism. As with a lot of games I write about, I played Alter Ego with my wife Dorte. She played with the female version, I with the male, and we took turns playing through a life phase at a time and comparing notes. Our agreed approach was to each play ourselves, making the choices we thought we would make at those ages in those situations. As we played, I found myself getting more and more angry at the game and sad for Dorte, as I kept getting to do cool and/or bold things and she kept being offered only meek girlie stuff. I got to go skydiving; she got to get an eyebrow tattoo. I slashed a hated teacher’s tires; she got a new hairdo. I got to buy video equipment or a flash new computer; she got to buy jewelry or “gourmet cooking accessories.” She always got offered the subordinate role, the pretty girl cheering on the boys who were actually doing something. I got to try out for the baseball team; she got to try out for the cheerleading squad. I got to start a rock band with some buddies; she got to call in to a radio show and win backstage passes to a concert (“Could you SCREAM?”).

Favaro’s concept of feminism feels at least two decades behind the times — i.e., about five decades behind our modern times. Alter Ego treats the decision to pick up a single restaurant tab for your steady boyfriend as a blow for “Woman’s Libbers” — when was the last time you heard that term? — everywhere, one so bold that it makes your boyfriend feel “uncomfortable” and emasculated. A male chauvinist you meet at work is just a mustache-twirling villain who says things absolutely no one would dare say openly even in 1986 and who has little to do with the real issues women still confront every day in the working world.

You have been going through a difficult time with an influential businessperson who seems to really enjoy making people miserable with his sexist attitudes, his arbitrary decision-making and his arrogance.

You get called into his office to take the heat for a relatively minor error. The conversation begins, "Look, Darling. I've always believed that a woman's place is in the home. Unfortunately, those bleeding hearts upstairs have made it impossible for me to deal 'man-to-man' around here. There are some problems here that I want resolved, AND NOW!"

One of the interstitial quotes Alter Ego occasionally puts up is this bit of condescension by Sigmund Freud: “The great question… which I have not been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?'” Peter J. Favaro, PhD, also doesn’t have a clue. I normally resist the urge to psychoanalyze the people who write the games I write about, but, given that Favaro spends the entirety of Alter Ego analyzing me and offering commentary and criticism on my every action, I’ll make a slight exception and wonder if this passage, which is worthy of a certain rotund cigar-chomping radio host, reflects deeper insecurities.

Mary Lou Stoker is a friend of your closest female companion and a staunch feminist. The truth is that she is not a feminist in the true sense of the word; she simply despises and resents men, misapplying the feminist philosophy to suit her needs.

One afternoon, you overhear Mary Lou telling your best friend that the love of your life "really doesn't give you that much room to breathe." She says, "I mean, he's okay, considering the rest of the garbage that's out there these days, but I wonder if she feels a little trapped in the same place day in and day out?" She goes on this way for quite a while.

My favorite, unintentionally revealing part of this is the phrase “the feminist philosophy,” as if feminists represent a political party — or conspiracy — who all march in lockstep to the same playbook.

The most cringe-worthy parts of Alter Ego as a whole are those parts of the female version that deal with the sexual side of puberty and adolescence. Really, can there be any worse subject for a less-than-subtle 28-year-old male writer to tackle? Despite close competition from the likes of discovering your breasts are growing, getting your first period, and having your first orgasm, I think your first visit to a gynecologist makes for the creepiest episode in the game; this fellow is actually far creepier than the Chester the Molester who tries to pick you up outside your school. After making inquiries with one or two women of my acquaintance, I’ve confirmed that if you’re spending any time at all “naked” in a gynecologist’s office then something is very, very wrong.

Your mother calls you in for a talk about something she says is "very very important." She thinks that it might be a good time to go for a checkup with a "gynecologist," a doctor who specializes in women.

Select a mood:

afraid X

comfortable

Select an action:

go for an exam X

don't go for an exam

On the way over, your mother explains to you, "It's a little embarrassing at first, but he really is a gentle doctor." You dwell for a moment on the word "he," and realize that a man is going to see and "mess around with" all of your most intimate parts.

Select an action:

change your mind and tell her you don't want to see a man doctor

go anyway X

The gynecologist is a very sweet old man. Most of the time you spend naked is with a nurse who helps prepare you for the exam. The doctor is kind enough to warm up the instruments before he examines you.

When the examination begins, he shows you various different parts of your reproductive system and teaches you how to give yourself a breast examination, which he says is very important.

He asks your mother if she would be kind enough to leave the room. When she does, he asks you whether you are sexually active and if you are using birth control. He then asks if you would like more information about birth control.

Select an action:

get more information

say, "no." X [Get me out of here!]

He sees that you are feeling a bit uncomfortable and tells you that if you ever need information about birth control to give the office a call. He leaves you with a little warning. "Don't experiment before you get the facts, young lady."

Alter Ego strictly enforces the law of social averages. There are very good design reasons that it can’t allow you to become an astronaut, a rock star, an international drug smuggler, or even a homeless tramp; doing so would invalidate virtually all of the other vignettes that deal with daily life as most Americans of the 1980s knew it. But if the emphasis on the ordinary is defensible given Alter Ego‘s design constraints, the reductive judgments the game is constantly making about your actions certainly are not. Alter Ego is forever telling you why you’ve done something, and then whether that’s good or bad. If you respond to a blue period by just “letting it pass,” it tells you you’re “denying your feelings” and that “it’s okay to feel blue some of the time.” (When did I say that it wasn’t?) If you fail to gush with loving support after your dad gets fired from his job, you’re scolded for not telling him “he is a worthwhile and cherished human being.” (What if I’ve always had a difficult relationship with him and can’t help but remember that he was never really there for me in similar situations, and thus my feelings are more complex than just a “cherishing”?) If you fail to volunteer time or money to a charity that knocks on your door, you’re called in so many words a selfish jerk who can’t be bothered to think of the children! (What if I’m a bit suspicious of big international charities, and prefer to do my giving in other ways?) If you commit suicide — presumably due to all that feeling-denying that was going on earlier — you’re told that suicide is always “an act of anger,” but the last laugh’s on you, because “the people you leave behind will try very hard to put this event in their pasts as quickly as possible.” (Suicide is way more complex than just another way of acting out, as someone with a PhD in Psychology really ought to know.) If you try to offer a little advice to a friend who’s having an affair, you’re mockingly told to butt out, “Sigmund.” (Oh, the irony…) When you have your inevitable midlife-crisis, you’re given this semantic drivel about “wishing” and “wanting”:

One of the key things to consider is the difference between WISHING and WANTING. You can spend the rest of your life WISHING for something magical to happen that will change your unsatisfying situation. If you WANT something badly enough, you do whatever is necessary to make it happen, even if it is difficult.

Playing Alter Ego today as a crotchety 42-year-old, my reaction to stuff like this is to ask what the hell do you know about it, Peter J. Favaro, PhD? No one has the right to pass such easy judgment on the complexities of life. If you’ve ever spent time flipping through self-help books, passages like those above may have a familiar ring, and for good reason: Favaro has since built a career around such pat aphorisms, writing a number of pop-psychology books and appearing on the low-hanging fruit of the talk-show circuit — places like The Montel Williams Show and Fox News morning shows — as a “television psychologist.”

I know I’ve been awfully hard on Favaro today, and perhaps not entirely fairly. His project was in a way doomed from the start. I’m sure that neither I, nor you, nor any one person could have done it justice, brilliant as the idea of it is. I’d therefore like to see a modern version of Alter Ego that would try a different approach. Instead of a single author, inevitably blinkered by her experiences and prejudices, I’d like to see a crowd-sourced Alter Ego. People from all over the world, and of all ages, races, genders, and sexualities, would be able to submit their own vignettes reflecting their own lived experiences. The result would be a constantly expanding tapestry of the human experience, accessible to anyone who ever felt an urge to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes. Rather than flatten the human experience into some idea of the psychologically normal, it would celebrate all of the different ways there are to think and feel and be.

As for the original Alter Ego, it did moderately well commercially; Favaro claims it earned him enough to buy “a house and a car.” Activision and Favaro made plans to release a follow-up called Child’s Play, “a humorous simulation about raising children,” but sweeping changes at Activision in the months after Alter Ego‘s release soon brought an end to that project, and with it Favaro’s career as a game designer.

Alter Ego enjoyed a big revival in the mid-2000s thanks to Dan Fabulich’s web-based version. He’s since also made it available as apps for Android, iOS, and even Kindle e-readers. It’s safe to say by now that many more people have played Alter Ego in its accessible modern incarnations than did so back in the day when it was a $35 boxed game. And indeed, while it does kind of annoy the hell out of me with its dodgy writing, lecturing authorial persona, and blinkered worldview, it’s still worth a look. Not only is it interesting purely for what it tries to do, but many other players genuinely enjoy it on its own terms. And hey, even if you feel like me about it you can still enjoy yourself a lot by making fun of it. Dorte and I had a blast doing that.

In that spirit, I’ll leave you with my favorite male-version/female-version juxtaposition of all.

The female version:

You are getting dressed one day and notice a small red mark on your lip. Could it be some kind of disease? You think about all the boys you've kissed in the past month and decide to kill anyone who has given you a terminal disease.

And the male version:

You are getting dressed one day and notice a small red mark on your penis. Could it be some kind of disease?

Maybe I should take back what I said about the female always getting the short end of the stick…

(Notable writings by and about Favaro can be found in the October 1982 Compute!; the April 1983 and October 1983 Creative Computing; the November 1984 Family Computing; and the November 1982, March 1983, August 1983, September 1983, and January 1984 SoftSide. His three pre-Alter Ego games that were mentioned in the text appeared in SoftSide Selections 54, 58, and 60.)