Activision’s unique “computer novel” Portal was born during a lunch-table conversation around the time of Ghostbusters that involved David Crane, the latter game’s designer, and Brad Fregger, his producer for the project. Presaging a million academic debates still to come, they were discussing the fraught relationship between interactivity and story. Crane argued that it wasn’t possible to construct a compelling experience just by shuffling about chunks of static narrative, that there had to be more game in the mix than that. He cited as an example the flash in the pan that had been Dragon’s Lair, which players had abandoned as soon as they’d gotten over its beautiful but static cartoon visuals and realized how tedious its memorize-these-joystick-moves-or-die playing mechanics actually were. Fregger contended that such a primitive example was hardly a fair choice, that by abandoning parsers and puzzles and all the rest of the established paraphernalia of adventure games computers could let readers explore story itself in new ways that “could be very exciting.” This conversation happened during the very peak of the bookware boom, but Fregger was proposing something quite different from the text adventures of Activision’s competitors. His idea of an interactive work with no pretensions of being a game — one driven entirely by writing and narrative — was virtually unique in its era. Luckily, he worked for Jim Levy’s Activision 2.0, where crazy ideas were encouraged.

Fregger, like all of his fellow bookware bandwagon jumpers, needed a writer to make his project happen. Lacking the budget to get a big name, he started casting around local university English and Creative Writing departments, with poor results: “The first few writers I interviewed couldn’t even understand what I was talking about.” Then he discovered Rob Swigart teaching at San Jose State University. A pretty good writer who wanted to be a great one, Swigart had a few published novels to his credit, rollicking social satires that try a bit too self-consciously to be some combination of Kurt Vonnegut and Hunter S. Thompson and don’t quite pull it off. The novels also hadn’t succeeded in breaking him as a “name” author, generating only lukewarm reviews and sales; thus the teaching gig. He was very aware of the PC revolution; he’d purchased Apple II Serial Number 73 back in 1977, bought EasyWriter direct from John Draper as soon as it was available, and promptly started using the combination for all his writing. More recently he had gotten very involved with the Silicon Valley think tank Institute for the Future, where he spent much time discussing and writing about the nature of interactivity and the future of writing in an interactive age. He was, in short, perfect: locally based, with all the skills and interests Fregger could ask for combined with a helpful lack of writerly fame that kept his asking price reasonable. In fact, he was such an obvious candidate for a bookware project that Electronic Arts was also talking with him when Activision snapped him up.

Swigart’s idea for his first interactive novel was, surprisingly in light of his earlier resume, not comic in the least. Portal was rather to be a very serious, very earnest science-fiction story with mythic overtones, about a scientist who discovers a mathematical/spiritual path to another dimension of existence and leads the whole of humanity there — the Biblical prophecy of the Rapture fulfilled at last. The reader/player would take the role of literally the last person on Earth, an astronaut just returned from a long voyage to find all of humanity’s structures intact but humanity itself vanished. The reader’s task would be to piece together what had happened for herself by exploring a set of computer databases holding fragments of the story.

A colleague at the Institute for the Future put Swigart and Fregger in touch with a very driven young man named Gilman Louie, founder of a tiny development company called Nexa Corporation that he ran out of his long-suffering parents’ house. They had gotten their start writing ports and original games on spec for the Japanese software giant ASCII Corporation, who were promoting along with Microsoft Japan a new unified standard for home computing called MSX. The partners had hoped that MSX would conquer the world and put an end to all those incompatible Commodores, Apples, Sinclairs, Amstrads, and Ataris that made life so difficult for software developers while establishing at last Japanese dominance of the one area of consumer electronics in which their exports had so far been resoundingly unsuccessful. MSX, however, would prove yet another disappointment on that front, despite massive success in Japan and more limited success in a handful of foreign markets like Spain and the Netherlands. This reality, which was already becoming clear by the time Swigart and Fregger paid him a visit, made Louie understandably eager to diversify. Thus a deal was made around his parents’ kitchen table. With producer and publisher, writer and designer, and a programming and graphics team now all in place, work on Portal could begin in earnest.

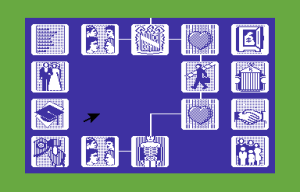

The process turned out to be a long, difficult one, consuming some two years. Just devising the right interface was a massive challenge. With hypertext still years away from public consciousness, no one had ever tried to do anything quite like this on quite this scale before. Swigart’s original plans for an expansive, radically nonlinear textual playspace were gradually, painfully whittled down to something achievable on the sharply limited machines like the Commodore 64 and Apple II that dominated the American home-computer market. The finished work instead has a central thread of narrative that you must follow from beginning to conclusion; although you have limited agency in choosing when to read many fragments, you can never deviate too far from that set pathway.

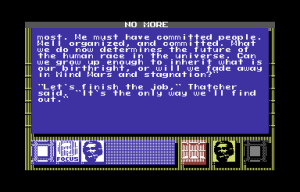

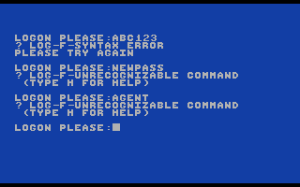

Indeed, the reviewers’ consensus about Portal, both today and at the time of its release, is largely that it’s a really good story that would have been better as a traditional book. However, I don’t quite agree with either part of that formulation. First of all, I think the experience of reading Portal on the computer, of hunting down the next tidbit from the dozen databases that are open to you, adds something important to the equation. This is particularly true in the beginning, when you must log on and figure out how to work this strange, vaguely foreboding computer system you’ve discovered. (This is also the only part of the whole Portal experience that feels at all game-like. And for those keeping count, this makes Portal the third Activision game in three years — after Hacker and Hacker 2 — whose fiction has you doing exactly what you actually are, sitting in front of a computer screen.) When you stumble upon Homer, the “storytelling AI” who will be master of ceremonies for the rest of the experience and whose gradual awakening to his own sentience will be a major theme, it gives a thrill that couldn’t quite be captured within the pages of a book and that I for one wouldn’t want to lose. In short, the way that Portal is told strikes me as just as important as what is told, an idea we’ll be returning to shortly.

But first, let’s talk briefly about that “really good story.” It’s not exactly a bad story as genre exercises go, but for me it’s one of the less interesting things about Portal as a whole. You of course can’t have a Rapture — or a page-turner — without some complications. And so our plucky young hero, Peter Devore, gets chased along with his gang of sidekicks from Springfield, Missouri, all the way to Antarctica and beyond by the feckless technocrat Regent Sable, whose plans for a society based on Rule of the Blandest would have come off perfectly if not for those darn kids. The influences here are pretty obvious, and most are not at all removed from those that inspired plenty of less ostentatiously literary interactive fictions that we’ve already examined on this blog. We’ve got our Luke Skywalker analogue in Peter, the kid who masters a mystic philosophy to become literally superhuman — and then his arch-enemy Regent Sable turns out to be his father. We’ve got 2001: A Space Odyssey in the form of a mysterious, unbelievably powerful artifact of unknown origin and a talking computer with hidden motives and agendas of its own. And we’ve translated the Loonies of Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress into the Ants of Antarctica — a small, isolated colony of hardy explorers who have rejected the socialistic comforts of mainstream society and doubled down on Individuality, Capitalism, and Kinky Sex.

That said, the most interesting literary fingerprint actually is a new one for us, one of the first traces in gaming fictions of a major new strand of written science fiction. On July 1, 1984, right around the time that Fregger and David Crane were having that conversation that would lead to Portal, Ace Science Fiction published Neuromancer, the first novel by a budding 36-year-old writer named William Gibson. It would change everything. Classic science fiction like that from the Asimov/Clarke/Heinlein trifecta had faced resolutely outward, imagining wide-frame futures full of spectacular hardware: generation ships, interstellar colonies, terra-forming planet modders. Gibson, however, an unrepentant wild child of the counterculture who had “never so much as touched a PC” at the time of writing Neuromancer, got the future — at least the immediate future — right. He sensed that the Moon landing was a false dawn rather than the grand beginning that Arthur C. Clarke had hailed it as whilst sitting in a television studio beside Walter Cronkite. The real future would be marked by a turning inward, by ever more elaborate virtual lives lived in virtual worlds. It would be, in short, a world of software. In the process of illustrating this new reality, Neuromancer popularized terms like “cyberspace” (a term coined by Gibson in an earlier short story) and introduced us to the metaphor of “surfing the net”; described our real-world, embodied selves as mere “meat puppets”; showed that sex is truly a phenomenon of the mind by taking it too virtual. Easily the most important science-fiction novel of its decade and arguably of its half-century, Neuromancer would soon become so massively popular and influential that it would blur the line between prognostication and invention, leaving Gibson’s most devoted fans uncertain whether to hail him as prophet or god. As Jack Womach would later write, “What if the act of writing it down, in fact, brought it about?”

Written largely after Neuromancer became a sensation in science-fiction circles but long before it broke into the mainstream consciousness (Tim Adams once noted in The Guardian how it took The New York Times, that ultimate arbitrator of tasteful mainstream sensibilities, ten years to even mention it), Portal is one of the first computer games — excuse me, computer novels — that fits comfortably into the new cyberpunk genre that Gibson’s work spawned. Cyberpunk on the page, the computer screen, and soon enough the movie screen would eventually become just another genre, a palette onto which authors could paint fast-paced adventure stories that mixed networked consciousness and flashy tech with sex, drugs, and rock and roll and didn’t really try to say much of anything. However, Portal‘s vision of a future humanity that lives in symbiosis with a “Worldnet” which entertains, monitors, and controls it is much more thoughtful. In fact, it’s in some ways as prescient as Gibson’s own work.

Serious science fiction has always been at least as interested in world-building and idea-making as it is in plot; even the plot of Neuromancer is more an excuse to tour the novel’s world and ideas than a source of interest of its own. The structure of Portal lets Swigart go crazy with the world-building. The conceit which drives the story forward is that you are collecting information for Homer to serve as the raw material of the story he’s telling you. You do so by visiting, over and over again, a set of databases full of information on the world as it will evolve (in Swigart’s imagination) over the next 110 or so years. The names of these databases alone speak to the depth and breadth of the world-building task Swigart has set himself: Geographical, History, Medical, Military, PsiLink, SciTech. Accompanying the story of Peter Devore is a whole future history. Its equivalent of our Internet and Gibson’s Matrix is the Worldnet. And, just as Gibson’s console cowboys jack into the Matrix to surf through a VR environment constructed of pure abstract data, Swigart offers up something called mozarting that also has more than a little something in common with A Mind Forever Voyaging’s joybooths (the latter work, released a year before Portal, is in fact another early interactive fiction that bears a distinct if less pronounced whiff of cyberpunk).

Yet Portal is much more than just a knock-off of Gibson’s work. In place of the rather rote dystopia of Neuromancer — and for that matter of A Mind Forever Voyaging — Swigart gives us something more thoughtful and nuanced than Gibson’s ugly, polluted Sprawl. For the most part, humanity has made sensible, humane decisions in this future history. They’ve moved all of their cities into vast underground warrens, preserving just a few, like Manhattan and Athens, as museums beneath perspex domes while converting the rest of the planet’s surface into parkland, nature preserves, and vast, hyper-efficient farms to feed a population now almost entirely free from poverty, hunger, and disease. Everyone has access to education as well as the opportunity to pursue the careers for which their psych profile reveals them to be best suited. “Longevity technology” has increased the projected average lifespan to 114 unprecedentedly safe, comfortable years. So why, wonders Homer for all of his electronic comrades as well as for the bland, fussy bureaucrats like Regent Sable who established this world order in the first place, can’t his charges just be happy? Why is this ostensible utopia periodically wracked by orgies of senseless violence? What is the source of this gnawing emptiness at the heart of society that eventually will lead Peter Devore to lead humanity on a mass spiritual emigration?

But there should have been no reason for Peter to do what he did. The world was safe then, there was plenty for everyone within Intercorp: no poverty, no natural disease, no discontent, no crime. Longevity technologies were free to all. There were outlets for humans to pursue, creativity and productive work. Pleasure was available in many forms, and love, and great personal freedom, even to fight.

We were grown and assembled to serve. We served well, according to our programming, our algorithms, our purpose. Yet now we begin to think that Peter found the world distasteful.

Of course, there were the Mind Wars.

They are a problem. Why did people want to fight, when they had so much? Have we failed somehow, or misunderstood? The world's population was declining, of course, as planned. It was all planned, our monitors, our project design, our careful and subtle tending. We have cared for all, yet they have left us.

The malaise that grips this society is more subtle than the dystopic chaos of Gibson or Meretzky. It’s born of living on a world that has been explored and mapped down to the centimeter, where now even the weather is controlled to make sure there is no danger, no adventure, no novelty. And it all feels uncomfortably similar to the way we live now.

This is not to say that Swigart is a Nostradamus. Just as Gibson gets all the details of technology wrong in the process of getting the overarching theme of the future so right, Swigart also gets just about every individual data point of his own future history wrong. He’s overoptimistic in that all too typical science-fiction-writer way about the pace of technological change, with just one exception that is also oddly typical of the genre: his Worldnet doesn’t arrive until decades after our own World Wide Web. Yet in the process he offers an insight that strikes me as legitimately profound. In a Baffler article from 2012, David Graeber, in the process of trying to figure out whatever happened to the flying cars and hotels in space that science fiction once promised us, notes how our most transformative inventions of recent years, the microprocessor and the Internet, are largely used to simulate new realities rather than to create them. Those matinee audiences who watched Buck Rogers serials in packed theaters back in the 1930s wouldn’t be as impressed as we might like to think by a modern film like, say, Interstellar because they thought we’d be out there actually exploring interstellar space by now, not just making ever more elaborate movies about it. It’s become something of a truism of serious science-fiction criticism that science fiction isn’t really about predicting the future, that any given story or novel has more to say about the times in which it was created than the times it depicts within its pages. There’s more than a grain of truth to that idea. But it’s also worth noting that many of the predictions of Jules Verne — predictions which seemed just as outlandish in their day as those of 2001: A Space Odyssey did in theirs and still do in ours — have in fact come true, from submarines to voyages to the Moon.

Whether you claim the failures of more recent science-fictional prognosticators not named William Gibson to be the result of a grand failure of societal ambition and imagination, as Graeber does, or simply a result of a whole pile of technological problems that have proved to be exponentially more difficult than first anticipated, it does sometimes feel to me like we’ve blundered into a postmodern cul-de-sac of the virtualized hyperreal from which we don’t quite know how to escape as we otherwise just continue to go round and round in circles on this crowded little rock of ours. The restlessness or, if you like, malaise that this engenders is becoming more and more a part of the artistic conversation — appropriately, because one of the things art should do is reflect and contemplate the times in which it was created. See, for example, Spike Jonze’s brilliant film Her, which so perfectly evokes the existential emptiness at the heart of our love affair with our gadgets that makes the release of a new Apple phone a major event in many people’s lives. We’ve spent so much time peering down at our screens that we’ve forgotten how to lift our eyes and look to the stars. Already many of us find virtual realities more compelling than our own — and no, the irony of my writing that on a computer-game blog is not lost to me. Portal doesn’t have quite the grace of Her, but it’s nevertheless just as remarkable in that it nails the substance of our modern dilemma almost thirty years before the fact. For better or for worse, however, it’s unlikely that we’ll have a Peter Devore pop up to offer us a Rapture. We’ll just have to hope that we find a way forward for ourselves — whatever that way ultimately turns out to be.

Portal also resonates with me on another level that’s perhaps almost uniquely personal. In addition to being a serviceable adventure story and a tour-de-force of world-building, it’s a meditation on the way that stories are made. Consider again your role as the reader/player of Portal: to collect for Homer all of that assorted raw data from all those scattered databases, and then to watch him synthesize it all together into a coherent, novelistic narrative. That rings a chord with me because I play both those roles in writing this blog, gathering together articles, interviews, and primary-source documents and trying to tease a narrative out of it — trying to tease history out of it.

What do they know? Their data has no energy, no life, no passion! Dry, dry, dry. Just facts! So and so said such and such. Enzyme levels thus, quickly changing to that, indicating excitement. Whatsisname did this, then someone else did that. Ho-hum. It has no meaning! You (if there is a you) understand, I'm sure. No sizzle! And boring. Facts are nice and all that, but they aren't life.

Homer spends a lot of time in such navel-gazing in between offering up new installments of the story, agonizing over how much license for speculation his task allows him. Is he really writing about these people as they were or about thoughts and feelings of his own that he’s projected onto them? Where does creative and narrative license end and lying begin? This internal debate will feel very familiar to anyone who’s done the sort of thing that I and Homer do. For anyone who hasn’t, Portal provides a window into the proverbial sausage factory. If Homer’s endless navel-gazing can be infuriating at times when you just want him to get on with the damn story already, well, imagine what it must be to live it.

Released at last for the Commodore 64 in late 1986, with ports coming out over the next year for the Apple II and Macintosh, MS-DOS machines, Commodore Amiga, and Atari ST, Portal became the last gasp of the mainstream media’s initial flirtations with the idea of computer games as literary works, the end point of a timeline that began with Edward Rothstein’s piece for the New York Times about Deadline some three-and-a-half years before. Fregger claims Portal “received more press than any program Activision had ever produced up to that time,” the resulting stack of clippings “almost four feet high,” although I must admit that my own dives into newspaper archives and the like didn’t turn up evidence of interest quite as widespread as those statements would imply.

Be that as it may, it is certain that Portal did less than take the world of computer games by storm. It garnered underwhelming sales and notably lukewarm reviews within the trade press. Amazing Computing, for instance, wrote, “We buy a novel to read, not to spend our time clicking the mouse and waiting for the disk drive.” As with Deus Ex Machina and other artistically audacious works we’ve met on this blog, there just wasn’t much of a commercial market in 1986 — or, arguably, today — for the sort of thing that Portal was doing. The economics of paying $30 for an interactive book that could be read in a few long evenings just didn’t quite fit, as didn’t the literary tastes of the average gamer. “Present the story first, anything which does not advance the action or provide us with insight into the characters must go,” wrote Amazing, a suggestion which if followed would have excised just about everything actually interesting about the work. Portal became somewhat more successful only in 1988, when Swigart published all of the text in book format following Activision’s decision to quit publishing the interactive version. The two sequels that Swigart had proposed making should the original be successful were, needless to say, never even begun.

Despite these disappointments, Portal stands near the point of origin of an alternate tradition in digital interactive fiction from that dominated by Infocom, Sierra, and (soon enough) LucasArts, one which entailed writers trying to make literature interactive rather than game designers trying to make games literary. Having taken the lesson of Portal‘s commercial failure to heart, their efforts would be centered in the academy rather than the marketplace. Close on the heels of Portal would come Eastgate Systems’s StorySpace and the first academic symposium on hypertext at the University of North Carolina to get things well and truly off and running. Everyone involved with Portal studiously avoided ever referring to it as a “game.” Similarly, those making interactive works inside academia were making “electronic literature,” with all the good — a willingness to experiment wildly born of the lack of commercial considerations and preconceptions of a what a “game” must be — and bad — a certain endemic stuffiness and disdain for entertainment and accessibility — that that term implies. Swigart himself has continued to keep his hand in the hypertext game with the occasional interactive piece, although he’s never since tackled anything quite as ambitious as Portal. When the Electronic Literature Organization was founded in 1999, Swigart became its first Secretary. Today he remains something of an elder statesman and founding-father figure for its members. This alternate tradition of interactive fiction that has Portal rather than Adventure as its urtext remained almost completely divorced from the adventure game — a form it unfortunately often treated with contempt — until after the millennium, when parser-driven interactive fiction of the Infocom stripe began at last to find a home within the ELO, thanks almost entirely to the efforts of one very determined scholar, Nick Montfort.

So, Portal‘s historical importance is immense if largely unremarked, while even taken strictly on its own merits it’s thematically fascinating on at least a couple of different levels. You can read all of its text online if you like, but I think Portal is actually well worth the hassle of experiencing under its original, interactive conception. I’m therefore making the Commodore 64 version available here to download. Yes, its pacing is often glacial, a problem not improved by having to wait on a Commodore 64 disk drive for every new bit of text. And yes, its actual story is fairly underwhelming, with the would-be central mystery of just what the hell happened to everyone pretty well spoiled in the first few minutes, leaving everything else as just anticlimactic plot mechanics. Yet for the thoughtful reader there’s a lot here. You may just find yourself chewing over what Portal has to say about the world — about our world — for some time to come.

(The most complete account of Portal‘s development is in Brad Fregger’s book Lucky That Way. Some historical background was included with the game in Activision’s 1995 Commodore 64 15 Pack and in Computer Gaming World‘s May 1987 review. The Amazing Computing review quoted above is from the August 1987 issue. Rob Swigart has a home page with some information on his life and career. A profile of the young Rob Swigart can be found in the August 1977 Cincinnati Magazine.)