Stan Kent and his company AstroSpace may have exited the stage, but Avant-Garde Publishing, the new owners of HES, weren’t ready to give up on Project: Space Station. They reached out to Larry Holland to finish the game.

Holland shares with Stan Kent some impressive academic credentials, but he’s otherwise his polar opposite: a quiet just-get-the-job-done sort who has always avoided interviews and public exposure as much as possible. After earning a Bachelors in anthropology and archaeology from Cornell in 1979, he spent two years out in the field, working on digs in Africa, Europe, and India, before starting on a PhD at Berkeley. He settled there near Silicon Valley just as home computers were beginning to take off. He bought himself one of the first Commodore 64s, learned to program it, and was hired by HES in early 1983 to port action games like Super Zaxxon to it. He proved himself clever and reliable at the work, enough so that it was decided to dump Project: Space Station in his lap. It was just the chance Holland needed to show what he could really do. He pared down and refined AstroSpace’s shaggy mixture of advocacy and simulation, synthesizing a bunch of disparate pieces that looked more like engineering tools than pieces of a game into something that fit on a single disk side and was actually fun — and all without sacrificing the spirit of the original concept.

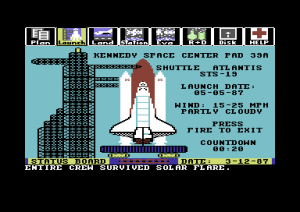

Project: Space Station starts you out on July 1, 1985, with two space shuttles, $10 billion(!), and high hopes. You’ll have to plan and build your station module by module, while also, this being the new era of space exploration, earning enough from commercial satellite launches and the results of the experiments you run up there to keep the project going. From the perspective of today especially, Project: Space Station is a simulation of an alternate history in which the American space station not only got funded and built in the 1980s but all of NASA’s manned-space initiatives — most notably the shuttle — lived up to all of their plans and hopes. In this timeline shuttle launches are truly routine. You can assign a couple of astronauts to a shuttle, launch it, bring them down a few days later after having delivered their payload, then launch them again a week later like the space truckers they are. In a small concession to reality, every ten launches or so the shuttle might lose some thermal tiles, thus needing an extra ten days or so for repairs, but the thing blessedly never blows up or burns up. You even have clients asking you to hoist satellites for them for $40 million to $70 million a shot, and the shuttle is cheap enough to operate that you can turn a profit on that; pack several satellites into the cargo bay and send ‘er up before your arch-rival, the European Space Agency with their boring unmanned rockets, steals the job from you.

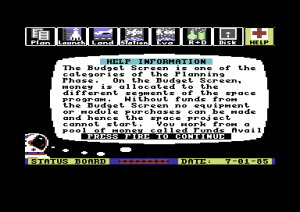

The first thing you notice when you first start Project: Space Station is how friendly it strains to be. I’ve made it a point to mention in the past how the innovations of the Lisa and Macintosh trickled down to cheaper machines in a way that gave the Apple computers influence far out of proportion to their actual sales numbers. That influence is all over Project: Space Station; this program simply couldn’t have existed a couple of years earlier. Everything is presented via icons and menus, navigable with the trusty joystick, while the space-station design screen has you sketching out your station by pulling modules into place with a “mouse” pointer. There’s even a — get this — context-sensitive help system to guide you through the game along with some canned tutorials to get you started. Hardware limitations inevitably restrict all of this in practice, but Project: Space Station feels like it was looking ahead about ten years into the future of software — or just looking very carefully at what was happening on the Mac, which largely amounted to the same thing.

The other obviously extraordinary thing about Project: Space Station is the fact that it runs entirely in real time. There were plenty of grand strategy games already available for machines like the Commodore 64; SSI alone had published dozens of them by 1985. But, true to that company’s roots in cardboard wargaming, most of these felt like tabletop rulesets that had been translated to the computer. Project: Space Station, however, is undeniably a born-and-bred computer game. There are no turns here. As you navigate through its screens the clock is constantly ticking, sometimes much to your consternation, as when you find yourself with research projects that need to be tweaked, a shuttle costing you money in space that needs to be landed ASAP, a precious satellite contract about to be awarded to those pesky Europeans, and another shuttle on the launch pad about to begin its countdown. Where do you begin? This game does nothing if not teach how to prioritize and how to manage your time. It also does a great job of not making you feel like you’re just tinkering with a dry spreadsheet, a syndrome that afflicted many other contemporary strategy games, a genre not exactly known for its graphics at a time when graphics in general were, shall we say, somewhat limited in comparison to today. Project: Space Station‘s graphics are actually quite nice for the era and the machine. But more importantly, you get to do such a variety of stuff in this game that it stays fresh and interesting for a surprisingly long time. When you’re tired of budgeting, there’s a shuttle to land via a real-time action game; when you’re tired of tweaking research projects, there’s that new laboratory module to move into place via an EVA.

So, let me walk you quickly through the different sections of the game, each of which is represented by and always accessible via its icon at the top of the screen.

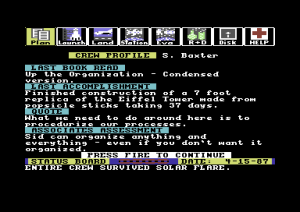

The Plan section is the expected spreadsheet portion of the game, where you allocate funds to your different departments; buy the actual pieces of the station which you’ll be assembling, erector-set-like, in orbit; hire and fire astronauts; and provision and schedule shuttle launches. The most interesting and surprising part of this section is the astronaut-selection process. Each of the 32 possible astronauts has not only a professional specialty but also a personality. You have to consider whom you put together, because personality clashes can and will result if you put, say, a control freak together with a more laissez-faire kind of fellow. You’ll grow attached to some of these folks, and you’ll feel awful if you kill one or more of them by stranding a shuttle in orbit or botching an EVA.

Shuttle launches are affected by the weather; you’ll want to watch it carefully, and delay the launch if conditions are too unfavorable. Occasional mechanical snafus will also cause delays. Once the candle is lit, you take control, guiding the shuttle into orbit via a little action game that doubtless would have horrified the original Project: Space Station team with its lack of realism but is nevertheless a nice, not-too-difficult break from the strategic side of the game. If you stray too far off course, the shuttle will end up parked in orbit far from your station, making any EVA operations to expand or repair it much more time consuming and hazardous.

Shuttle landings also involve a simple action game. Rough landings can result in damage to the shuttle and extra repair time before it can fly again.

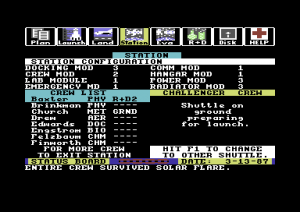

The Station section is there mainly to let you transfer astronauts between a shuttle in orbit, which can hold up to six people, and the station, whose capacity depends on how many crew modules you’ve bought, flown into orbit, and linked up, along with how much additional station infrastructure you’ve built to support the crew: power modules, radiator modules to disperse heat from the power modules, emergency modules to protect the astronauts from the occasional solar flares. And of course there’s not much point in having people at the station without something for them to do — meaning research projects, which require laboratory modules, which require yet more power modules, which… you get the picture.

The EVA section is the most fanciful part of the game. You venture outside shuttle and station using worker pods that have everything to do with 2001: A Space Odyssey and nothing to do with anything NASA was likely to come up with in the mid-1980s. You use the pods to construct the station, clear occasional debris that’s made its way into the station’s orbit, and launch commercial satellites; in the screenshot above, I’ve just attached a Payload Assist Module to a satellite to boost it into geosynchronous orbit. It’s very easy to run out of fuel or damage a pod so badly that it’s no longer functional. When that happens, you’d best have a backup pod that you can use to rescue the first before oxygen runs out. Once you’ve experienced a single time the excruciation of waiting for an astronaut to die from oxygen deprivation, unable to do anything about it, you’ll make sure you always do, believe me.

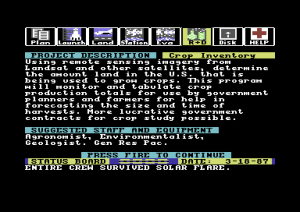

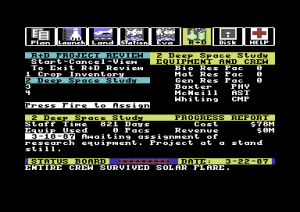

Finally there’s the real heart of the game, the R & D section; after all, it does bill itself on the box as a “science simulation in space.” You can have up to four research projects running at once, assuming you have a station that can support them. While you receive a generous initial budget which you can supplement with satellite launches, your research should eventually become the heart of your revenue stream, as it is the heart of the game’s rhetorical argument for a space station as a fundamentally practical, commercial proposition that will eventually pay for itself and then some. Some projects can also yield practical improvements that will make your station run more efficiently. There are 40 impressively specific projects to choose from, divided into 9 categories: Agriculture, Astronomy, Bio Medical, Earth Watch, Geology, Materials Science, Meteorology, Physics, and Space Technology. It’s a big thrill when one yields a major breakthrough, enough so that you’ll probably be willing to ignore questions like why it’s necessary for people in space to examine the satellite imagery used to make a crop survey.

I don’t want to overstate the case for Project: Space Station. While thoroughly entertaining in its early stages, it does have a litany of little problems that are very likely to turn you off eventually. Many involve research. If you don’t happen to be watching an R & D project when a milestone is completed, it’s very easy to miss it; once replaced by something else, each R & D notification from each project is lost forever whether you’ve actually read it or not. That’s a very bad thing because each project yields exactly three milestones, after which it continues to suck money from your budget but doesn’t earn you much of anything. You’re thus often left uncertain whether a given project has run its course or a big windfall might be just around the corner. Even more infuriating is when a project starts saying a “key scientist” is needed for research to continue, without telling you whom or even what type of scientist you should be looking for. Gameplay then devolves into a tedious — and expensive — ferrying up of shuttleloads of possibilities and swapping them in one at a time, whilst you wonder what the hell sort of a research team would just tell you they feel the need for someone else but not whom or what for.

There are a number of other areas like this where the game’s ambitions outrun the capabilities of an 8-bit 64 K computer with a blocky low-resolution screen, where you feel like the game just isn’t telling you things you really ought to be able to know. Which research projects are expected to yield the most immediate returns for the early days of your station? When can you expect the next injection of financial assistance from Congress, and how much will it be? If a research team is suffering personality clashes, who exactly is having a problem with whom? And then there’s the goal problem, in the sense that there really isn’t one. The whole affair must presumably spin down into entropy at some point, when you’ve done all of the research projects and can no longer sustain your station, although it seems that can take a very long time; on his now-defunct blog dedicated to the game, Geof F. Morris posted screenshots of a station that lasted into 2007 in game years. I would venture to guess that Larry Holland was not so much unaware of these problems as just unable to push the hardware any further to correct them. Project: Space Station‘s sensibility is so modern that it can lead us to expect more from it than a Commodore 64 can deliver even under the control of a great programmer.

The game didn’t have much commercial luck. It was released at last in late 1985, some three years after Stan Kent had first conceived it and just a few months before the Challenger, which features as one of the two shuttles in the game, blew up on its way to orbit and suddenly made Project: Space Station‘s sunny optimism about a future in space feel tragically anachronistic. Avant-Garde Publishing went under shortly thereafter, marking the final end of the HES label. Yet Project: Space Station wasn’t dead yet. It ended up in the hands of Accolade, who rereleased it in 1987 as a member of their Advantage line of budget games, with some small but important changes: the Challenger was replaced by the Discovery, and the starting date was moved up to 1987. It made no great impact then either, and faded away quietly into commercial oblivion at last.

Surprisingly given its (lack of) commercial performance, Project: Space Station spawned a modest, oddly specific sub-genre of space-station-building games that also included Electronic Arts’s Earth Orbit Stations as well as Space MAX from the perfectly named Final Frontier Software and the more fanciful E.S.S. Mega from Coktel Visions, which replaced American with European boosterism. Buzz Aldrin’s Race into Space, a management simulation of the Moon race, might also be considered something of a spiritual heir. All except that last share with the space shuttle itself today a certain melancholia. Thoroughly of their time as they are, they can be a bit disconcerting to us in ours, showing as they do ambitions never fulfilled, grand adventures never quite undertaken.

Project: Space Station is even more fascinating as a piece of history than many of the titles I write about, being a document of our sunniest expectations for a future in space prior to the Challenger explosion that changed everything. But even taken as just a game, it’s impressive and noble enough that I’d recommend you play it for a little while in spite of its issues. You can download the original Commodore 64 version from here if you like, or find its ports to the Apple II and IBM PC on other sites. Most games — even the equally-noble-in-its-own-way Ultima IV — treat life so cheaply, sending you off to slaughter in the name of becoming a hero. It’s nice to play a game that’s all about preserving the precious lives of your astronauts, that shows that a game can be absolutely without violence and still be riveting, that shows that heroism need not come with a body count. Would that ludic history had many more like it.

(Larry Holland — who in later years tended to be billed as Lawrence Holland — has generally managed to avoid talking much about his personal life and background as well as his early career. The best print source is a profile in the spring 1992 issue of LucasArts’s newsletter The Adventurer. While I generally try to avoid wikis or overly fannish sources, his page on Wookiepedia is also very complete and appears to collect just about everything we know about him, scanty though it may be.)