If Ian Bell and David Braben, brashly young and brashly nerdy in that traditional math-and-science sort of way, became the baseline expectation for British game developers, Mike Singleton, creator of the beloved adventure/strategy hybrid The Lords of Midnight, was the outlier. He was older for one thing, already in his mid-thirties at the peak of his fame in the mid-1980s. And his background was also different. After a failed stab at becoming a theoretical physicist, Singleton had graduated university with of all things a degree in English, and spent a decade teaching the subject before computers arrived to provide an outlet for his latent talents for game design and programming. As Singleton himself put it, this background gave him an advantage over many of his peers in that “I am able to spell correctly, thank goodness.” More significantly, there’s a certain sense of nuance, even of grandeur, to The Lords of Midnight and some of his other games that distinguishes them from the more typical teenage-Dungeon-Master virtual worlds that crowded them for space on store shelves. His road from English teacher to one of the most famous developers in Britain not named Bell or Braben began in the late 1970s with, of all things, a betting shop.

The shop in question was owned by a friend in his home town of Liverpool. Said proprietor was always complaining about the math involved in some of the more elaborate bets favored by his patrons, such as the “around the clock,” which consisted of thirteen individual wagers placed on three different horses. Singleton offered to help out by writing some routines on the Sinclair programmable calculator he’d just received as a birthday gift. When that looked promising, they spent £100 on a Texas Instruments TI-59 calculator to take things to the next level. When that also went well, they upgraded yet again, this time to a Commodore PET with the idea of creating a complete PET-based software suite for managing all of the functions of a betting shop — a package which they could sell. But it didn’t work out. They just couldn’t figure a way to get the software to run fast enough to keep up with the fingers of an experienced bookmaker with a line of eager punters to service.

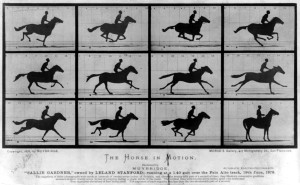

Looking around for some alternative use for their hardware investment, Singleton and his partner came up with an idea that was, in its way, visionary. What if they let customers play and bet on the computer whilst hanging about the shop waiting for race results? Singleton’s first game (of a sort, anyway), Computer Race, was born for this mercenary purpose. Customers who fed it money were rewarded with an onscreen, animated horse race. Singleton based his horses’ movements on a picture to be found on the wall of half the betting shops in Britain, Eadweard Muybridge’s “The Horse in Motion.”

The outcome of each race was determined randomly, with the customary small edge for the house. Again, Singleton and partner envisioned selling the game to betting shops all over the country. But again, their hopes came to little. This time they were undone by a legal rather than a technical problem. They ran afoul of British laws designed to keep betting shops as unwelcoming as possible. Singleton: “Having chairs is a little bit dicey, you might be contravening the laws — you’re encouraging people to go in a betting shop.” After narrowly losing a test prosecution, they decided the plan was too risky to go ahead with. It seemed the era of virtual racing must still be some years away. They sold exactly one Computer Race setup, to a betting shop in Ireland not subject to British law, where it played merrily for some years.

Having failed to become a gambling mogul, Singleton “took the computer and ran” to see if he could find another way to earn back its purchase price. Already a pretty good assembly-language programmer thanks to his experience with the betting shop, he wrote an action game he named Space Ace and sold it to PETSoft, one of the first software publishers to spring up in Britain. It sold 200 to 300 copies — not bad given the size of the British computer market at the time. But Singleton sensed a bigger opportunity in the offing. Despite their name, PETSoft had entered negotiations with Sinclair Research to market a line of programs for that company’s first microcomputer, the ZX80. Unfortunately, the deal fell through. Fortunately, Singleton was a persistent sort. He called Clive Sinclair directly to offer his services as an experienced programmer with a published game to his credit. Uncle Clive took a shine to him, and invited him up to Cambridge to pick up a prototype of and sign a contract to develop some games for Sinclair’s second machine, the ZX81.

To say the scope of possibility was limited on the ZX81 hardly begins to state the case; the machine had all of 1 K of memory. Over his two-week break from teaching that Christmas of 1980, Singleton knocked out half a dozen simple BASIC games and shipped them back to Sinclair to become Games Pack I. Now he began to reap some real financial rewards from his efforts at last: Games Pack I, that product of two weeks’ effort, earned him an astonishing £6000 during the following year. By way of perspective, know that £6000 was the average Briton’s yearly salary in 1980. “It was the best rate of pay I’ve ever had or am ever likely to have!” noted Singleton wryly.

If he’d been chasing the money until this point, that didn’t mean that Singleton didn’t genuinely love games. He was an avid board gamer and would-be game designer from childhood; he designed his first “James Bond-style” board game at 13, and retained an enduring fascination with Go throughout his life. In 1977 he discovered his first computer game (again, of a sort). Starweb was a play-by-mail game from the pioneer of the format, the American company Flying Buffalo. A harbinger of countless space-based grand-strategy games to come, Starweb required that players communicate each move on paper via post, writing their commands out using an arcane language to be entered into the game’s host, an exotic Raytheon 704 minicomputer. Once all of the players’ moves were entered, the Raytheon spit out the results in another arcane format that was, just for extra fun, completely different from the command-entry format. These reports were sent to players by return post. When two players met in the game, each was provided with her counterpart’s address, so they could talk amongst themselves and plot alliances and wars. And so it went, at a cost of $1.75 per move. Despite the extra postage cost and time delay entailed by his living in far-off England, Singleton was entranced. His first game lasted two years, ending in his victory over about fifteen others. He continued to play avidly thereafter. (Starweb, now approaching its 40th anniversary, is still an ongoing concern. The only obvious change from the game Singleton knew is that the communication can now be done via email.)

With that £6000 burning a hole in his pocket, Singleton now decided to press his faithful PET into service yet again to be the host of Starlord, a, shall we say, tribute to Starweb more accessible to British and European gamers. The PET got some pricey exotic technology which ate up a good chunk of the £6000: a hard disk and a color ink-jet printer. The latter allowed him to send players full-color maps of the galaxy and their position in it. Indeed, he made the entire game more colorful and friendly than its inspiration: “order forms” were now used to communicate your moves and their results were sent back in plain, readable English along with the map and copious status reports. All for the modest fee of £1.25 per turn. It was a lot of fiddly work for Singleton, but with players soon numbering in the hundreds (the game would peak around early 1984 with over 700), it was also quite profitable. When he realized he was earning more from Starlord than he was from teaching, he quit his day job.

He supplemented his Starlord income with more action games for the low-cost microcomputers that were now starting to flood Britain. First came Shadowfax, an unauthorized Lord of the Rings knockoff of the sort the rising profile of the computer-games industry wouldn’t allow for much longer. It had you playing Gandalf riding against the Black Riders; he reused the horse animations from Computer Race. It was also the first sign of a Tolkien fixation that would flower more elaborately in The Lords of Midnight. Shadowfax was followed by Siege and then Snake Pit (Singleton’s personal favorite from this early stage of his career). All were released for the Commodore VIC-20 and later the Sinclair Spectrum on the Postern label, and all did quite well.

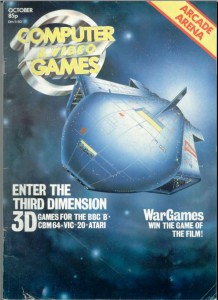

He went through a phase of being fascinated with the possibilities for 3D displays — meaning 3D in the sense of those funny glasses you wear at the movies, not 3D rendering as in Elite. 3 Deep Space, released initially for the BBC Micro — Singleton apparently never met a machine he didn’t want to program — would be, Computer and Video Games magazine confidently predicted, “the first of a flood of stereoscopic games to hit the micro shops.” Or not, although Singleton gave it a hell of a try, porting 3 Deep Space to the Commodore VIC-20 and 64 as well as the Spectrum and publishing a bunch of 3D type-in listings along with the bound-in glasses to view them in the same issue of Computer and Video Games that made the aforementioned prediction (funny how that worked out). 3 Deep Space became the first flop of Singleton’s career.

His close relationship with Computer and Video Games was thanks to his friendship with that innovative magazine’s founder and editor, Terry Pratt. He even once ran a special simplified version of Starlord (called The Seventh Empire) just for the magazine’s readers. Pratt left Computer and Video Games in 1983 to take charge of a new publisher being set up by the media conglomerate EMAP, to be called Beyond Software. He immediately started urging Singleton to leave Postern and come write games for him. In September of 1983 Singleton invited Pratt to his home in Chester, where they discussed three different ideas that might be turned into games. By the time of a 2004 interview for Retro Gamer magazine Singleton had forgotten what two of them were, but the third had been indelibly stamped not only in his head but in that of many thousands of gamers. It was a new graphics technique he called “landscaping” which he believed could be made to work on the Speccy. Given a grid-based map containing forests, plains, mountains, lakes, etc., landscaping would let him programmatically generate and draw a first-person view from any square on the grid, facing in any of the eight compass directions. He thought he might use it in a game far more ambitious than his previous simple action titles: something like the current bestseller The Hobbit, only much, much better. He believed he could pack a 64 X 64-square “game board” into his Spectrum’s 48 K of memory. This added up to 4096 individual locations to visit, each with eight possible views: over 32,000 individual pictures to see. The ad copy would practically write itself. Pratt told him to go for it: “I would first implement the technique and then, providing it worked, we’d go ahead with the full game.”

As would be the case with David Braben’s first rotating 3D spaceships, from this technical germ would be born a spectacularly innovative game design. Singleton envisioned a strategic war game that would play like an adventure game. Instead of viewing the conflict from on-high, you would see it through the eyes of those whose actions you controlled, whom you would be able to switch among and order about individually. The experiential aspect of war games, the role of the imagination in evoking their unfolding narratives of conflict in the mind’s eye, had always been an important part of the form’s appeal, much as stuffy grognards muttering about analyzing history and scoffing at games of mere make-believe might have sometimes been loath to admit it. Now Singleton could really bring that aspect to the fore, really let you live the experience through your generals’ eyes in a way that felt more like an adventure game. Yet there would be no parser, and text would be kept to a minimum to save memory for code. Singleton, who like many hardcore strategy gamers had little use for traditional adventures with their static worlds and static puzzles, was determined that his game be an unpredictable, dynamic, replayable experience like the cardboard war games he loved: “Routes aren’t dictated by the programmer in advance. You are in control of the main characters and their ultimate destiny.”

Of course, he would need a fictional context for the game. He thought of adopting the setting of a new play-by-mail design he’d been working on called The Lords of Atlantis, but Pratt wasn’t excited about that. Anyway, an underwater setting probably wasn’t worth the trouble. A medieval fantasy setting, he decided, would yield the best combination of popular appeal and ease of implementation, and be a natural fit for the sensibility of a Tolkien fan like himself. He decided to make his land a cold, icebound place simply because he “liked the combination” of the Spectrum’s shades of white and blue. He conceived of a land in which seasons last eons. His story would take place on the winter solstice, the darkest, coldest point just before a hoped-for new dawn and gradual thaw. The Lords of Atlantis became The Lords of Midnight. Now he started in earnest to build a world:

I drew a large map, which I still have, in nice felt-tip colours. It isn’t quite as difficult as it sounds and really I bet Tolkien did the same — you start off with a few word endings and tack different syllables on the front until you come up with something that sounds good, so you sit there going “Ushgarak, Ashgarak, Ighrem” to yourself until you get something that sounds nice or horrible according to what you want. [In reality the linguist Tolkien, who started with rigorously worked-out made-up languages and wrote The Lord of the Rings and the rest of the lore of Middle Earth largely to learn about the people speaking them, would have been aghast.] And once I got the map, then I started doing the story before I got on with any programming, and it was really the story that built up the atmosphere. I managed to get through the story quite quickly, in about three weeks. And that clarified all the major characters.

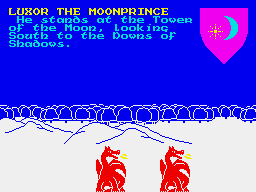

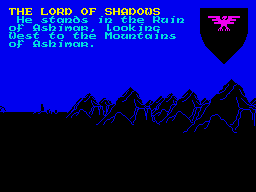

The story Singleton wrote, the preamble to the War of the Solstice, would eventually be included with the game as a novella. Taken on one level it’s just another Tolkien knockoff, if reasonably well written as such things go. We’ve got the usual stand-ins for Sauron (Lord Doomdark), Aragorn (Luxor), Frodo (Morkin), Elrond (Corleth), Gandalf (Rorthron), Gollum (Fawkrin). The game itself flies its Tolkien flag with equal pride. There are two ways to win which neatly parallel the two stories told in The Two Towers and The Return of the King: use Luxor (Aragorn) and as many of the thirty other Lords of the Free as he can rally to his banner to defeat Doomdark (Sauron) militarily, or sneak Morkin (Frodo) deep into Doomdark’s realm to destroy the Ice Crown (One Ring), source of Doomdark’s power.

Yet there’s a sense of the timeless to The Lords of Midnight which is seldom seen in other games then or now. Singleton does not just appropriate the surface tropes of The Lord of the Rings but also manages to capture some of its epic grandeur. In their advertising copy, Beyond would ceaselessly pound on that word “epic”: “The Lords of Midnight is not simply an adventure game nor simply a war game. It is really a new type that we have chosen to call an epic game, for as you play The Lords of Midnight you will be writing a new chapter in the history of the peoples of the Free.”

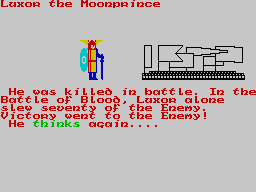

“Epic” is a word, like “tragedy” or “hero,” that’s been overused by our Hollywoodized culture to the point of meaninglessness; these days movies based on toy robots are epic sagas, and that party your friendly local teenager went to last weekend was epic, dude. The Lords of Midnight, however, reaches back to the word as it applies to The Iliad, The Odyssey, Paradise Lost, and, yes, Tolkien’s modern epic The Lord of the Rings. Not that I’m making direct artistic comparisons here, mind you. It’s just that there’s a similar if more modest windy majesty blowing through Mike Singleton’s land of Midnight, something I can’t quite put my finger on that makes it more than your typical fantasy pastiche. One need only read a few comments from the many players who remember the game well to realize that I’m not the only one to feel it. More so than strategic depth (which it has to a surprising degree; folks continue to discuss and refine their strategies to this day) or anything else, that feeling seems to be the defining trait of The Lords of Midnight for most players. It manages to be epic in the classical sense when other games settle for adjectives like “exciting” or “interesting” or “immersive.” It’s in the graphics; it’s in the simple elegance of the mechanics (there are only a few actions each character can perform); it’s even in the text, which is stately, literate, and dignified while necessarily remaining very succinct. Even when you lose — and you will lose, early and often, before you work out how everything works and develop a serviceable battle plan — you feel like the destruction of the People of the Free also has an epic resonance of its own; the story of Hector can be as compelling as that of Odysseus, after all.

Although they are very different games with very different personalities, The Lords of Midnight and Elite have a similar sense of scope about them. Both are incredibly complex systems in light of the hardware on which they run. More importantly, however, both are masterful examples of the Eliza effect writ large: they make you want to believe — make you actively imagine — that there is more to their universes than there actually is. Paradoxically, their very verisimilitude can be linked back to their hardware limitations. With scant memory and no disk storage to fall back upon, their creators were forced to generate most of their content procedurally rather than constantly slurping up static assets — whether in the form of graphics, sounds, data, or just text — from disk. The result feels unpredictable, flexible, and responsive to you in a way that most contemporary “epic” American adventure and CRPG games, which by The Lords of Midnight‘s time routinely spanned multiple disk sides, never manage with all their reams of static data. Taken purely in terms of the feeling of scope and possibility that they evoke, The Lords of Midnight and Elite are still some of the most awe-inspiring virtual worlds ever made.

Whatever other qualities The Lords of Midnight shares with Elite, it had nothing like that game’s extended gestation time. Having spent the last three months of 1983 developing the landscaping technique and designing the game and its world and of course writing the novella, Singleton didn’t start actually coding the game until January. He finished in a bare three more months of twelve-hour days, turning the whole thing in to Pratt that April. The whole project consumed less than seven months from start to finish. Within weeks, the game was on shelves. The final product was, in defiance of Beyond’s less than rigorous testing regime and the hard-won wisdom of anyone who’s ever programmed seriously, very nearly bug free. It’s a remarkable achievement indeed, one of the last of the great lone-wolf games. Singleton had done everything: design, graphics, coding, even writing most of the manual in the form of that novella. Technology and ever-greater player expectations would soon make such an approach, even for an apparent near savant like Singleton, untenable.

Beyond, who had failed to make much of a splash with their first few titles, knew they had something special in The Lords of Midnight. They began previewing the game even before Singleton was completely done with it, creating a buzz of interest. By now it had become standard practice in Britain for publishers of hot new games to tell players to contact them as soon as they won for booty and ten minutes of fame that was either explicitly or implicitly up for grabs to the quickest and the cleverest. Recognizing the game’s literary texture, Beyond came up with one of the craziest such contests ever staged. Prospective winners, they said, should laboriously print every single screen of their experience, using a command Singleton had helpfully added for that purpose, to create “an illustrated history of the War of the Solstice.” The first person to send in a complete history of a winning game would become “the coauthor of a fantasy novel based around your adventures in Midnight,” which Beyond would “arrange for a fantasy writer to turn into a book to be published by one of the UK’s top fantasy publishers.” An audacious idea indeed, but one that turned into a fiasco. Whatever agreements Beyond had or thought they had, they ultimately couldn’t find any name author to write such a book nor anyone to publish it. The winning player, who had sent in his thick sheaf of papers just two weeks after the game was released, was quietly pacified with some alternate prizes and the whole episode flushed down the memory hole as quietly as Beyond could manage.

That hiccup aside, everything went smashingly. The Lords of Midnight sold 10,000 copies in its first two weeks at the unusually expensive price of £10. It turned into a solid success, albeit one that hovered around the tenth position on the sales charts for months on end rather than a chart-topper. No worries; that felt somehow appropriate, given the sort of slow-building but ultimately entrancing experience it is to play. Almost every Speccy-focused or platform-agnostic games magazine in existence published tips, maps, and often complete strategic solutions for both the quest victory and the military victory over the next year. There’s no better illustration of the esteem in which it came to be held by at least the more cerebral wing of Speccy gamers than Crash magazine’s big 1984 year-end poll. The Lords of Midnight was voted “Best Text/Graphical Adventure” by no less than 51% of voters; its closest competition came in the form of Sherlock with all of 10% of the vote. The game’s reputation only continued to build as the years passed and magazines like Crash turned more and more to dwell on past glories in light of the slowly dwindling supply of new Speccy games. In 1991 they dubbed it and its sequel “probably the two most exciting computer games ever written.” Its position in Spectrum lore remains inviolate today. (Beyond also funded ports to the Commodore 64 and Amstrad CPC, but those, while very positively reviewed and successful enough, never quite attracted the worship that Speccy lovers continue to bestow on the original.)

That aforementioned sequel, Doomdark’s Revenge, appeared, following another frenzy of design and programming on Singleton’s part, just in time for Christmas 1984. It was largely what one might expect: an even larger map, a few new commands to try, “few major surprises” (as Crash admitted in an otherwise glowing review). It was undoubtedly (as another reviewer noted) “more sophisticated and more difficult,” and became another big success for Beyond, but most today feel it failed to improve on its predecessor as either game or fiction. While it’s not a bad game by any stretch, even Singleton himself eventually came to recognize the original as superior. Ironically, some of its flaws were down to its increased “sophistication,” particularly its elaborations on the rather simplistic AI of the original. Singleton:

With 20/20 hindsight, the way the characters in Doomdark’s Revenge made and broke alliances of their own accord and moved about the map on their own quests made things too unpredictable for the sort of strategic planning a player could do in Lords. Perhaps some other feedback — in the form of news or intelligence information — to the player on what was actually going on in the (largely unseen) background between the other characters would have made this feature really work.

That said, I should also note that there is a substantial minority of players who prefer the larger map and more unpredictable play of Doomdark’s Revenge. Whatever else we say about it, the fact that a program running on a 48 K Spectrum is making and breaking alliances amongst non-player characters is pretty amazing in the same way as are the dynamic characters of The Hobbit and Sherlock — and, perhaps, similarly problematic from the standpoint of playability, falling into an uncanny valley of the AI which lessens rather than furthers the Eliza effect.

The scope of The Lords of Midnight and Doomdark’s Revenge as well as innovative techniques like landscaping were so inspiring that Singleton couldn’t help but become a hacking hero even amongst Spectrum owners who lacked the patience to sit down and properly play the games. While he would never challenge Bell and Braben in the mainstream-fame sweepstakes, he was a big, big man in British computing for several years, with the magazines all jostling to interview him about not only coding and design but also such pressing concerns as his favorite food (steak and chips) and favorite pop groups (Pink Floyd, Deep Purple, and Led Zeppelin; 1970s hard rock was quite the staple amongst 1980s hackers).

But the interviewers’ favorite question was always about the status of The Eye of the Moon, the final game in what had been promised from the first would be a trilogy (how could such an unabashed Tolkien pastiche be anything else?). Singleton delivered tidbits about what the last game would entail, including a yet larger map and a different structure that would break the game (and the map) into a number of smaller quests, each building upon the previous and increasing in difficulty, to keep it from getting overwhelming in the way in which Doomdark’s Revenge was already arguably verging. But first he wanted to write a new, different sort of game for the Commodore 64, his first with a collaborator — thus marking the end of this lonest of lone-wolf coders, a sign of changing times if ever there was one — called Quake Minus One. Then Beyond, after barely two years as an independent entity, got bought by the giant British Telecomsoft, who were throwing their weight and money around the British games industry like crazy during the mid-1980s. BT had already, you may remember, outbid everyone else for the biggest game in the industry, Elite. They had also bought a Star Trek license from Paramount, and Singleton was drafted to work on that game for a while while The Eye of the Moon continued to languish. The Star Trek project didn’t go well at all, and he left to form his own small development house, Maelstrom Games. In the end, The Eye of the Moon never appeared, doomed by some combination of other pressing priorities, over-ambition, and legal uncertainty about who really owned what; Singleton and Pratt, you see, hadn’t bothered with contracts, only “gentleman’s agreements,” which was fine until a big, fussy company like BT came into the picture. Maelstrom did finally make and release an alternative concept as a third game, Lords of Midnight 3: The Citadel, in 1995 on the Domark label, but probably shouldn’t have bothered; few have much good to say about that effort.

Singleton’s career after his glory years of the mid-1980s is a motley mix of worthy and similarly underwhelming games, with one more unimpeachable classic, 1989’s Midwinter, thrown in for good measure. Lords of Midnight 3 marked his last project in the role of designer. He remained in the industry until his untimely death in 2012, but was forced to content himself with lower-profile, mostly purely technical roles on big teams, working on games whose titles sometimes sound like something from an Onion parody of manic videogame culture: HSX: Hypersonic Extreme, Wrath Unleashed. A long, long way from the stately dignity of The Lords of Midnight…

Having praised that game so effusively here, I should note before concluding that it isn’t as playable as, say, Elite. Formulating a strategy and keeping track of up to 32 individual leaders of the Free, not to mention Doomdark’s hordes, all but requires extensive notes and visual aids. The map views and more usable status screens that a modern strategy game of this ilk would have are painfully missing, leaving your own elbow grease as the only viable alternative. Perhaps the most practical approach is to print out one of the detailed maps published by one of the magazines on the biggest sheet of paper you can find, then to borrow some counters to use on it from the nearest handy board game. I’ve included a pretty good map, from Crash‘s July 1991 issue, along with the Spectrum tape image and the manual in a zip file which you’re welcome to download.

If all that sounds like too much effort, I highly recommend that you check out Chris Wild’s loving remake for iOS, Android, OS X, and Windows. It adds exactly those conveniences that can feel so painfully missing to modern sensibilities while still preserving the atmosphere and wonder of the original. Either way, by all means play it if you haven’t already. It’s one of the greats — and, particularly when taken in tandem with Midwinter, more than legacy enough for anyone.

(Sources: Crash of June 1984, January 1985, February 1985, March 1985, June 1987, April 1989, September 1991; Micro Adventurer of August 1984, November 1984; Personal Computer Games of August 1984; Your Computer of April 1986, December 1987; Big K of July 1984; Computer and Video Games 1985 Yearbook and of May 1982, January 1983, October 1983; Popular Computing Weekly of November 29 1984, March 13 1986; Retro Gamer #4. The painted flavor illustrations were taken from the August 1984 issue of Personal Computer Games.)