As 1983 transitioned into 1984, the British games industry’s fortunes were soaring alongside those of its star platform, the Sinclair Spectrum. Mainstream press coverage soared right along with sales. Having not experienced the arcade- and console-videogame boom and crash to the extent of the United States, the press in Britain lacked a certain ennui that infected coverage of computer entertainment in that country. Thus picking up a tabloid newspaper really could make you think that games and their makers had arrived as mainstream entertainment, while several specialized weekly newsletters devoted to casual computing could be found at any newsstand, full of all the latest gossip. Trip Hawkins and Electronic Arts, who were earnestly trying to manufacture just this kind of mass-market buzz around their games and their “electronic artists” in the U.S. and largely failing, must have been green with envy. Of course, Britain’s homegrown electronic artists were also garnering a whole lot of money as well as a whole lot of press attention, giving Britons their first real exposure to the software superstar, generally in the form of a skinny, socially awkward young man rather incongruously sporting a Ferrari and a designer suit.

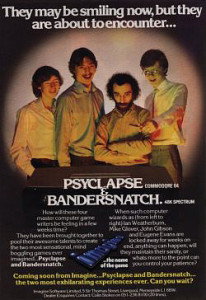

Imagine Software was the very personification of all this hype and excess. Founded by a few bright young sparks in Liverpool in 1982, Imagine burst to prominence and crazy profitability on the back of a slick action game called Arcadia, one of the early Speccy showcases which first made that machine the most popular gaming platform in the country. Thus when Imagine suddenly collapsed in about the most dramatic fashion imaginable in June of 1984 — employees returned from lunch to find the doors barred and their offices occupied by bailiffs working on behalf of Imagine’s creditors, with the whole thing being filmed for national television — it was tempting indeed to conflate their fate with the prospects of the industry as a whole. In truth, Imagine had worked hard to deserve their fate by being richly, conspicuously stupid. They invested in vanity projects like a misbegotten would-be advertising agency called Studio Sing; they refused to hire a single proper, professional accountant (perhaps because they didn’t want to hear what she might say); they twice moved into bigger, flashier offices before the lease on the previous had expired, thus paying double or triple rents for months at a stretch when they couldn’t begin to fill even one of their properties; they threw huge piles of cash into a never-released “mega-game” to be called Bandersnatch which they planned to sell for £40 (the typical going rate for a game at the time was about £5 or £6) and about which nobody was quite sure what it was supposed to be; they allowed their staff of artists and programmers complete “creative freedom,” which translated into many of them not really doing much of anything at all. Against all this, the Ferraris and racing motorcycles everyone at the company seemed to own represented a fairly modest problem.

It was also true, however, that the British software industry as a whole was bound for a stern reckoning with reality, just as was the American. Unlike the American, the British industry was also forced to contend with what they claimed was a booming trade in not just pirating (that was something the Americans knew all too much about) but commercial counterfeiting, a byproduct of the fact that most software was still distributed on cassettes in Britain. These were easy and cheap to duplicate in large quantities, and the simplistic packaging still common in the industry was also quite easy to copy well enough to get the job done. Counterfeiters, industry insiders claimed, could be found selling their wares at every flea market and village festival in Britain. Some even started their own little mail-order operations, selling through advertisements in newspapers. The industry claimed counterfeiters and pirates were costing them at least £100 million every year.

It’s difficult to assess the veracity of such claims. Certainly the games industry in Britain as well as elsewhere has a long history of overheated, overly alarmist rhetoric on the subject, which can perhaps make one more dismissive than one should be of legitimate concerns. What is clear is that, whatever the cause, the software industry didn’t grow in 1984 like it had in 1983. There were now simply too many publishers competing for the same customers. The prudent professionals like Alfred Milgrom of Melbourne House and David Ward of Ocean survived; the muddle-minded amateurs like the boys at Imagine were left with only their memories of one hell of a ride. The shakeout was inevitably wrenching, enough so that the more heatedly apocalyptic predictions for, as it was dubbed in a trade paper, “this tormented industry of ours” can be forgiven. Roger Kean offered a more balanced take in an editorial in Crash magazine:

There is nothing new in this; it seems inevitable that all “new” industries must start in back bedrooms and move to the conglomerate boardroom. If an industry is worth it, big money will move in. Competition increases, tougher marketing emerges, and the under-capitalized pioneer suffers. The benefits of programmers marketing their games through the larger software houses shouldn’t be overlooked though. The programmer is free to concentrate on what he does best while being linked to sufficient finance to market the game well, and at the same time is freed from the real headache of all companies — financial controls.

Melbourne House aside, most of the biggest of the big boys weren’t heavily invested in adventure games. Britain would never have another adventure phenomenon quite like The Hobbit. What it got instead was something that is in its way more inspiring. To program a sellable arcade game on even a simple machine like the Spectrum required quite a depth of knowledge in assembly language and the quirks of the Speccy itself. However, an adventure game was a less daunting prospect, especially with the aid of a tool like The Quill. Accordingly, new adventure games appeared by the handful virtually every week, sometimes from established publishers but also from plenty of teenagers possessed of an entrepreneurial bent, blank cassettes, and Ziploc baggies. This output dwarfed that of the U.S. in quantity if not in quality; World of Spectrum currently has archived 2217 commercial text adventures for the Speccy alone, and I’d venture to guess that at least that many more have been lost to history. Few of them would ever threaten to crack the software top ten, but they nevertheless fueled a thriving cult of eager players.

To sort through this flood in any rigorous way would require more time and dedication than I can muster. Having already looked at Sherlock, the biggest adventure of the year, we’ll just dip in another toe or two before moving on, checking in on a couple of other friends we already met in earlier articles. Being part of the less roller-coastery adventure scene, both Peter Killworth and the Austin family who ran Level 9 weathered the year’s storms quite comfortably.

The connection between Cambridge University’s Phoenix mainframe culture and Acornsoft continued to hold strong in 1984, with Peter Killworth continuing to serve as the conduit. Having ported the Phoenix game Hamil to the BBC Micro the previous year, Killworth did two more direct ports this year. One, of Rod Underwood’s 1980 game Quondam, is of particular value for Phoenix historians: the original, you see, is one of at least two Phoenix games to have been lost entirely in their original incarnations, and thus Killworth’s version represents our only way to play it today. (Sadly, the other — Xerb by Andrew Lipson — would seem to truly be lost forever.) Killworth’s other port was a technical tour de force that consumed most of a year: he managed to cram all of the monumental Acheton onto two BBC Micro disks, using one as a database to fetch text into memory as needed. That dependence on disk storage cut into sales severely; disk drives were still a relative rarity on British home computers, even on the fairly expensive BBC Micro line. But if nothing else Killworth and Acornsoft had bragging rights as purveyors of easily the biggest adventure game yet to appear on a microcomputer, on either side of the Atlantic. Acheton and Quondam otherwise remain the same sort of exercise in mathematics and masochism as the Phoenix/Acornsoft titles I’ve already discussed, so I won’t belabor them any more here. By now we know what we’re getting into with these games.

Level 9 celebrated the New Year with a new game — literally; they started selling it to mail-order customers on January 1. Lords of Time is unusual in being one of very few Level 9 games not solely designed by Pete Austin. Its germ was a proposal sent to the company by a fan named Sue Gazzard, “mother of two boys and reluctant housewife.” The Austins liked her idea for a time-traveling adventure inspired by a certain long-running British science-fiction series so much that they asked her to design it for them, with Pete in the role of programmer and occasional co-designer. Before release Gazzard’s original title of Time Lords became Lords of Time and the more overt Doctor Who references were smoothed away. Yes, the days when Level 9 could innocently release a trio of games that amounted to Lord of the Rings fan fiction were behind them; they would soon be scrubbing those games similarly clean of their inspiration, yet another sign of a maturing industry.

Lords of Time marked the end of an era in another sense: it was the last Level 9 game without pictures. In the eyes of Level 9, the success of The Hobbit had made them a veritable commercial necessity. Most other publishers seemed to agree. Absent an Infocom to fly the pure-text standard proudly, almost every high-profile British adventure game from here on would have to have pictures, despite the resource drain they represented on little computers already being pushed to their limit. (The Acornsoft adventures were among the few exceptions — but they were already becoming something of a specialized taste anyway.)

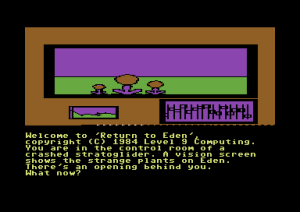

Having decided to take the plunge, the Austin brothers managed using their usual technical wizardry to pack an absurd number of pictures into a tiny amount of memory. Pete claimed that they could fit 300 pictures into 6 or 7 K of memory using an ultra-compressed version of the vector-graphics techniques Ken Williams had first employed for Mystery House and The Wizard and the Princess in the U.S. The end result was not aesthetically masterful, but there was something to be said for giving the people what they wanted. The first Level 9 game to include graphics was Return to Eden, second in the Silicon Dreams trilogy they had begun with Snowball.

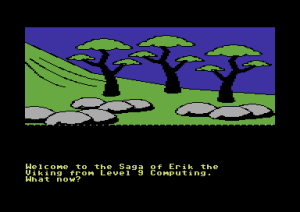

They rounded out the year with a third game, which appeared under the imprint of Mosaic Publishing rather than their own. The British equivalent to the American Telarium, Mosaic was busy pushing out an ambitious lineup of bookware, including titles based on books by Harry Harrison, Dick Francis, and Michael Moorcock. Level 9’s contribution was The Saga of Erik the Viking, a ludic sequel to the very popular 1983 children’s book by the improbably versatile Terry Jones of Monty Python fame.

Before I started writing this blog, I didn’t know nearly as much about Level 9’s games as a person who already years ago presumed to write a history of interactive fiction probably should have. Given their popular reputation as “the British Infocom” (admittedly, a title also sometimes ascribed to their later rivals Magnetic Scrolls), I dearly wanted to enjoy their games in the course of remedying that. But I must confess I’m finding that easier said than done. Snowball gave me hope that Level 9 was maturing, both with its more coherent fictional context and its fairer — albeit by no means entirely fair — puzzles, but this trio of games represents if anything a step backward. While I can overlook a lot of parser limitations and some strangled prose in light of the games needing to run on a 48 K machine with no recourse to disk-based virtual memory and now the added requirement of pictures, the unsolvable puzzles and the unnecessary cruelties are harder to forgive. There’s a locked door in Lords of Time that can be opened only by typing the magic word “EUREKA.” The only hint given for this is the fact that the door happens to be in an inventor’s laboratory. Otherwise, zilch — not even a nudge that you’re expected to use a secret word at all as opposed to opening the door by some more physical means. No wonder that programs to list the parsing vocabulary of Level 9 games were such a hot item in the magazines of this period. This sort of puzzle always frustrates me because it’s so… well, somehow dishonest. It’s easy and cheap to make a puzzle, or a game, that’s impossible to solve. The art and the craft come in making one that’s interesting, challenging, and solvable.

Return to Eden and Erik the Viking don’t feature any one puzzle quite so absurd, but in the aggregate are just about as impossible to solve and equally rife with annoyances and boring things required just for the hell of it. Eden, for instance, features a helicopter which constantly patrols overhead looking for you. You must “HIDE” every time it appears, which sometimes seems like every other turn. This goes on for literally most of the game; miss an appearance and it’s instant death. In no universe is this sort of thing remotely fun. Meanwhile the carefully worked-out setting of Eden‘s predecessor has been largely replaced with one more typical of adventure games — i.e., one a bit more on the absurd side.

That said, Level 9’s stellar contemporary reputation isn’t hard to understand. Thanks to their compression wizardry, they offered far more to do in every game than virtually anyone else, while their prose was generally a cut or two above the average and even their parser, while limited, was less limited than most. But I’m afraid their games — or at least those of this era — haven’t aged as well as one might wish. In the defense of Level 9 and others working the British market, I should note again that they were contending with horribly restrictive hardware in comparison to their American counterparts. The fact that they got as much game and as much text and graphics as they did into 48 K or (absent the graphics) even as little as 32 K of memory is remarkable in itself.

Still, the most remarkable and inspiring of all aspects of the British scene were all those amateur and semi-amateur creators making games for themselves with The Quill and other tools. They would become — and far sooner than the bigger publishers dreamed — the eventual face of interactive fiction. I probably haven’t quite given them their due, and probably won’t in the future, but I want to at least give them one more round of resounding lip service here.

Yet text adventures were not the most important games to come out of Britain in 1984. Indeed, for all its commercial uncertainty 1984 was an artistic year for the ages, one full of iconic titles and stone-cold classics, arguably the gaming year of the decade in Britain. I’d be truly remiss to not look at this creative explosion in other genres for which the British computers were, truth be told, probably better suited than displaying streams of hand-crafted text. So, next time we’ll jump into the first of a few of the most important and interesting titles from one hell of a crowded field.

(Paul Anderson and Bruce Everiss, respectively the maker and one of the stars of the BBC’s 1984 documentary on the British games industry that captured Imagine’s downfall, were reunited in 2011 at BAFTA for an interesting discussion. Other useful sources for this article: the Your Computer of November 1984; Crash of July 1985; Computer and Video Games of May 1984; and Micro Adventurer of July 1984. Oh, and feel free to download Peter Killworth’s two games of 1984 as well as Level 9’s three in versions for, depending on the game, the BBC Micro or Commodore 64.)