(Wikimedia Commons: Jcb-caz-11)

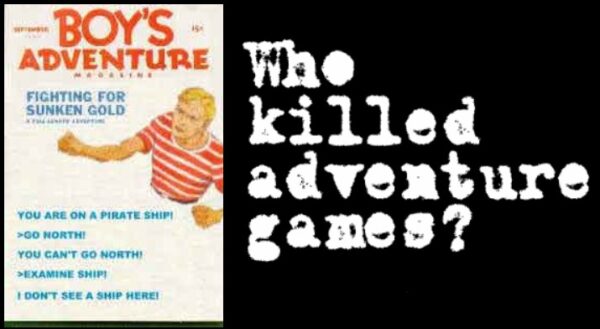

Believe that there is a secret and you will feel an initiate. It doesn’t cost a thing. Create an enormous hope that can never be eradicated because there is no root. Ancestors that never were will never tell you that you betrayed them. Create a truth with fuzzy edges; when someone tries to define it, you repudiate him. Why go on writing novels? Rewrite history.

— Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

Before all of the conspiracies, there was just a village.

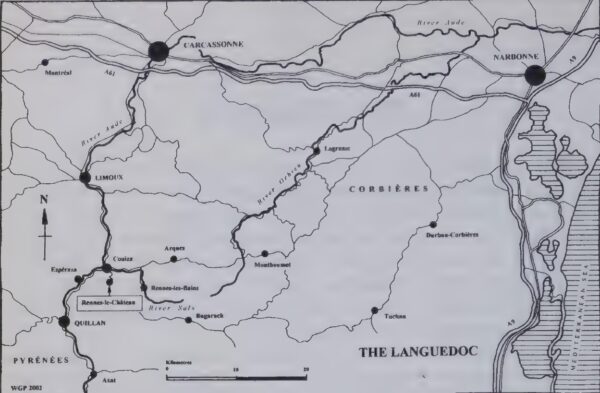

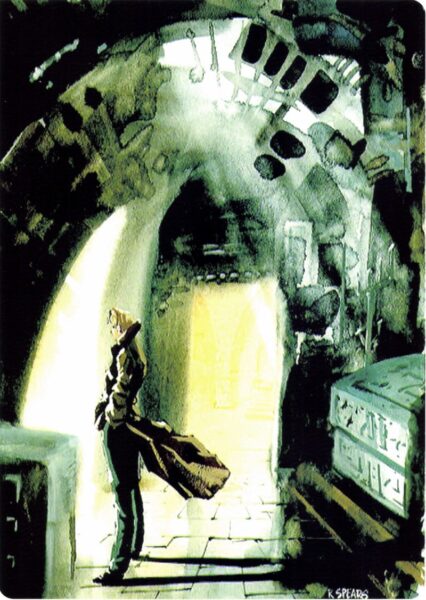

Rennes-le-Château sits perched atop a 300-meter-high promontory in the foothills of the Pyrenees Mountains. It has today a permanent population of fewer than 100 souls, who are clustered together on a plateau approximately 200 meters long by 100 meters wide. The only way to reach the village is by walking, cycling, or driving up a single narrow, twisting four-kilometer road that leaves from the closest neighboring town of Couiza (population 1100) and terminates here. But if there is only one physical road to Rennes-le-Château, there are a thousand or more imaginative ones. It is the Rome of the conspiratorial view of history, the place to which all conspiracy theories seem to lead sooner or later. Once you reach the village, whether in person or merely in spirit, there is literally nowhere else to go.

It may feel like a place out of myth, but it is not one without a website. During the high season, at least half of the single access road’s traffic consists of tourist buses. Their windows act as frames for the portraits of their eager passengers, visions of arcane mysteries swirling almost visibly around their heads like halos or thought bubbles, placed there by the guide at the front of the bus who knows perfectly well what stories she needs to recite to butter her bread. When the visitors pour out of their buses at the top of the hill, the villagers greet them with a smile, if sometimes a weary one. Whatever its drawbacks, living in one of the world’s most unlikely tourist traps is an undeniable improvement over the farming or mining by which their parents or grandparents made a living.

Rennes-le-Château owes its place on so many package-tour itineraries to the insatiability of the human appetite to believe weird shit. For every man, woman, and child who lives in the village today, there have been six or seven books published that prominently feature it. If we wind up nuclear-bombing or fossil-fueling or populist-politicking our way back to the Stone Age in the near future, there will still be some of us sitting around in our caves after the apocalypse, prattling on about Mary Magdalene and holy bloodlines and Knights Templar — always Knights Templar — to distract from the wolves howling in the lonely desolation outside. For a really good sinister conspiracy theory is counterintuitively cozy, what with the way it collapses the amorphous mass of real history, where cause and effect are as muddled as are heroes and villains, into a comforting clockwork mechanism of cogs in cogs. Small wonder that pseudo-history tends to thrive best when real life seems most vexed and confusing.

Rennes-le-Château lies within Occitania, the most southeasterly of the eighteen administrative regions of modern-day France. But for centuries the largest portion of this region, including the one that contains our village, was known as the Languedoc, a name by which it is still colloquially referred to this day. The Languedoc has long been characterized by a stubborn independent streak and an uneasy relationship with the powers that be in far-off Paris. To this day, some of the locals there prefer to speak their own language of Occitan, a direct descendant of the Latin spoken by the Romans who first settled here a century before the birth of Jesus Christ, rather than the language spoken by the rest of France.

Humans have been living in the Languedoc since 5000 BC at the latest; Neolithic cave dwellings have been found in many of the cliff faces that dot this craggy region. When the Romans arrived circa 120 BC, they brought with them bureaucracy, literacy, and in time Christianity in return for the ores and minerals of which the earth of the Languedoc is rich, from iron to copper, lead to gold. They may have built a village on the promontory where Rennes-le-Château stands today, or a villa, or a temple, or a fortress, or most probably nothing at all.

The Romans were eventually displaced by the Visigoths, who were on a tear after sacking Rome itself in AD 410. They evolved a civilization far more sophisticated than their barbarous reputation. Once the most febrile stage of their conquering was over, the Languedoc came to mark the northernmost part of their empire, which otherwise filled most of the Iberian Peninsula to the south. Further north was the burgeoning kingdom of the Franks, the forefather of the nation we know as France.

Some have connected our promontory with a major regional center of the Visigoths, which appears in some of the scant surviving records from the period under the name of Rhedae. But this idea appears to be, like so much about the story of Rennes-le-Château, an example of wishful thinking. Rhedae was supposed to have had a population of up to 30,000 people, meaning it would have had to have sprawled well beyond the promontory itself. Yet there is no trace in the surrounding countryside of the debris a settlement of that size should have left behind. Coins, jewelry, and axe blades should have been regularly churned to the surface by the farmers who have worked the land around here for centuries — not to mention the thousands of amateur archeologists who have descended on the area since Rennes-le-Château became such a nexus of conspiracy theories.

At any rate, the end came for the Visigoths at the beginning of the eighth century, when the Iberian Peninsula was invaded by Arab Muslim armies which had crossed the Mediterranean from Africa. The Muslims pressed northward from Iberia, taking the Languedoc and the entire southern half of modern France, until they were finally stopped by the Franks near Poitiers in 732. The Franks then pushed them back roughly as far as the modern border between France and Spain.

Yet the same Frankish kings who had triumphed over the fearsome Muslim armies found the settled inhabitants of the Languedoc a tougher nut to crack. The craggy landscape, it seemed, bred equally craggy souls. The region became a patchwork of small fiefdoms, home to a people who continued to hew to their own culture and language. Even the vaunted Charlemagne was able to fully assimilate the Languedoc into his empire only briefly.

One of the independent lords built a castle — a château in French — along with an accompanying church at the top of our promontory around the year 1000; this marks the first point where we can say with absolute certainty that people had begun to live there year-round. We don’t know precisely who built the castle, or why, beyond noting that high ground like this is always a natural place to fortify. It is likewise unclear by what name the complex was known. The name of Rennes doesn’t appear to have marked the site until the eighteenth century, Rennes-le-Château not until the nineteenth — by which time, ironically, the titular castle was no more than a romantic-looking ruin.

In the middle of the twelfth century, the Languedoc demonstrated its independent streak in the most flagrant possible fashion, when it became the locus of a breakaway sect of Christianity known as the Cathars, one of a succession of “proto-Protestant” groups who predated Martin Luther. In fact, the Cathars’ ideas were much more radical than those of even that radical reformer. Borrowing from the texts of the ancient Gnostic Christians, they thought that Jesus Christ had been an angel, an ethereal being whose physical form was only an illusion, who by his very nature could not have been physically killed and brought back to life, who had only created the illusion of these events. As if that wasn’t heretical enough, they also believed that there were two gods rather than one, an evil God of the Earth who was the protagonist of the Old Testament and a loving God of the Heavens who had announced his arrival in mortal affairs through the angel Jesus. They believed that the popes in Rome were the servants, wittingly or unwittingly, of the bad god rather than the good.

Of course, such a slate of beliefs was a recipe for trouble in Medieval Europe, and trouble the Cathars soon got. Pope Innocent III declared a Crusade against them in 1208. Savage warfare consumed the Languedoc for decades; whether and in what capacity the castle at Rennes was involved is unknown. Matters finally came to a head in 1243, when the heart of the Cathar army was besieged at the Château de Montségur, just 35 kilometers west of Rennes. On March 12, 1244, the starving remnants of the Cathar defenders embraced their martyrdom willingly, marching out of their castle’s gate with linked arms to face grisly death at the hands of the papist antichrist’s minions.

But it has long been said that, before they did so, they managed to sneak some great treasure past the enemy and hide it away somewhere. Some say it was the treasure of Solomon’s Temple, which was stolen from Jerusalem and taken to his own capital by the Roman general Titus in AD 70, then stolen again and brought to the Languedoc by the Visigoths. Some say the treasure might include the Holy Grail that was used to catch some of Jesus’s sacred blood at the crucifixion. (The fact that the Cathars didn’t believe that Jesus had a physical form from which to bleed real blood seems to have bothered remarkably few of the seekers of this “Cathar Treasure” over the years.) There is a legend about a Languedoc shepherd boy who in 1645 fell down into a hole while searching for a lost lamb; there he found skeletons surrounded by great heaps of gold. He filled his hat with gold and returned to his village, only to be stoned to death as a thief. (Justice was apparently even harsher than we imagine it to have been in that century, and the normal spirit of human curiosity strangely lacking.) This, then, is the original would-be treasure of the Languedoc. Rest assured that there will be others.

With the crushing of the Cathars, the Languedoc was firmly incorporated into the kingdom of France for the first time. From here, its history becomes a part of the history of France, much though some of its people may resist that notion. At the risk of offending these folks, we shall skip forward now, all the way to the late nineteenth century, by which time the castle on our promontory has been long abandoned and the rest of the misnamed Rennes-le-Château is a tidy if nondescript village of farmers and miners, population about 300 people, enough to support a Catholic priest of their own in their little Church of Saint Marie Madeleine. (This church may or may not be the one that was first built in the year 1000 or earlier; a fifteenth-century map of the local diocese shows two churches on the promontory, the other one being known as the Church of Saint Pierre. Even if it is the newer of the two, however, the Church of Saint Marie Madeleine is still at least 700 years old, because it is mentioned by name in an inventory dating from 1185.)

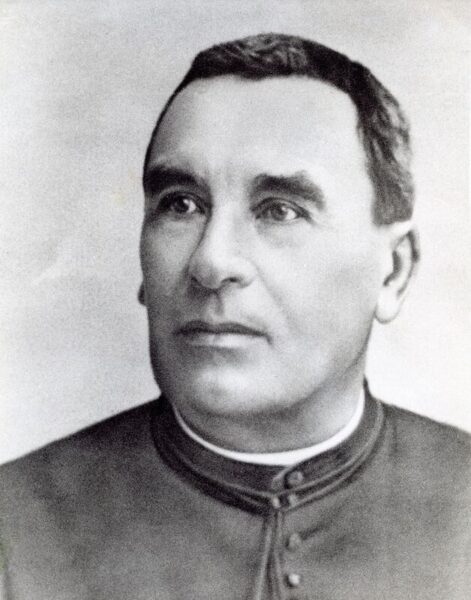

In 1885, Rennes-le-Château was assigned a 33-year-old priest named François-Bérenger Saunière, a native of the Languedoc who had been ordained in Carcassonne, the nearest cathedral town. Initially, he seemed to serve his flock faithfully and unremarkably enough. For six years after his arrival, nothing untoward occurred.

Then, in 1891, he took it upon himself to repair the high altar of his church. Inside one of the altar’s pillars, workers found some hollow wooden tubes containing documents written in Latin. They took them directly to Saunière, he being the only person in the village with the ability to read them.

Not long afterward, Saunière launched a new program of building and renovation, on a scale dwarfing the repair of a single altar. He remodeled the interior of his church in a striking and often jarring Gothic style, built a new chapel in the cemetery, laid out a decorative grotto, built a water tower for his parishioners, and graded the road still used by all of those tourist buses of today. The crowning glory was an elegant Mediterranean-style residence which Saunière dubbed the Villa Béthanie. Behind its high fence could be found a dramatic garden running right up to the edge of the promontory, an ornate orangery, and a neoclassical observation tower offering gorgeous views. In the base of this latter structure, which Saunière named the Tour Magdala, was to be found his library, housing his impressive collection of occult books.

The villagers would continue to talk about the salad days of Saunière for decades after the priest was no longer with them; some of their descendants continue to talk about them today. It is said that opera divas, high-ranking members of the French cabinet, and scions of the Habsburg dynasty came to stay in the villa. Saunière himself was frequently away from home, on jaunts that seemed to span the width and breadth of Europe. No one knew for sure where the money for all of this was coming from, but the rumor mill had it that the priest must have found a hidden treasure somewhere close to the village. The money certainly wasn’t coming from the Catholic Church, whose representatives were as flummoxed by what was going on in Rennes-le-Château as everyone else.

In 1910, the bishop of Carcassonne demanded that Saunière tell him plainly how he was funding all of this construction. Saunière flatly refused to do so. As a result, he was defrocked by an ecclesiastical court on December 5, 1911, temporarily at first and then permanently, once it had become clear that he intended to remain obdurate on this issue.

But Saunière simply refused to leave Rennes-le-Château in the aftermath of the verdict. He set up an altar inside his house and held Masses there for any who wished to come, in competition with the new priest who performed the same service inside the church that Saunière had remodeled so audaciously. He stayed a squatter on the territory of the Catholic Church until his death in 1917. When he was lying on his deathbed, a priest grudgingly agreed to come in from a neighboring parish to hear his Confession and administer the Last Rites. Real or purported witnesses have said that this priest came out of the sickroom looking visibly shaken, muttering that Saunière’s sins had been so immense that he had been unable to give the dying man the absolution he required to enter the Kingdom of God.

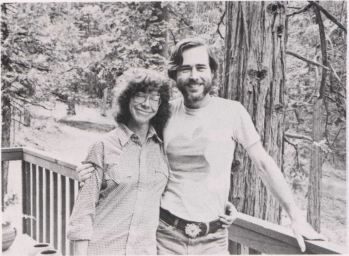

Albert Salamon, right, sits with Noël Corbu, on the boozy night in January of 1956 that injected the treasure of Rennes-le-Château into the mass-media bloodstream.

The foregoing have been the broad historical facts surrounding Rennes-le-Château, to whatever extent we are able to discern them. The story of how these facts evolved — some might say, were twisted — into one of the most prominent conspiracy theories of modern times is in some ways even more interesting. This tale begins less than three decades after the death of Bérenger Saunière, with the arrival in Rennes-le-Château of an inveterate dreamer, schemer, and chancer named Noël Corbu.

A venturesome streak ran through the Corbu family; Noël’s older brother Pierre had been an aviator who disappeared while trying to fly from Paris to New York in an experimental aircraft, just weeks before Charles Lindbergh became one of the most famous men in the world by accomplishing the feat in reverse. (So thin is the line between historical oblivion and eternal fame.) Born in Paris in 1912, Noël Corbu invested in airlines rather than becoming a pilot himself, then ran a pasta factory and tried his hand at writing detective novels. During the Nazi occupation of France, he started a black-market-smuggling operation in the Languedoc town of Perpignant, providing luxury goods to the Germans and French alike, whoever could afford to pay him. Alas, what he had seen as nothing more nefarious than a business opportunity primed for the taking got him tarred as a collaborator once the Nazi-installed Vichy regime was toppled. In 1945, he and his wife and two children made a hasty exit to the town of Bugarach, just twelve kilometers from Rennes-le-Château.

His new neighbors told him some of the rumors that swirled around the tiny but imposingly situated village and its former priest — rumors which were at this time still local to the area. If Bérenger Saunière’s will was to be believed, he had died penniless, except for the beautiful residence in which he had expired. This he had willed to, of all people, his housekeeper, a woman named Marie Dénaraud who, it was rumored, may have done more for him in his bedroom than wash the rugs, drapes, and linens. If Saunière had found a treasure, his home was surely the most logical first place to look for the booty, or at least for a clue as to its current whereabouts. Dénaraud was still living in the villa in 1945. Thoroughly intrigued, Noël Corbu decided to go and see her.

One glance at the Villa Béthanie was enough to tell him that, if there was treasure still hidden inside its walls, Marie Dénaraud hadn’t figured out how to make it liquid. She had sold the priest’s occult library to an antiquarian bookstore in Britain well before the war, but she hadn’t been seen hawking any gold or jewels. The place was in serious disrepair: the garden overgrown with weeds, the shutters falling off the windows, the once-gleaming steel frame of the orangery now more rust than metal. The woman who answered his knock on the front door was in no better condition. Dénaraud was a slatternly scarecrow who looked like she hadn’t eaten a decent meal in years.

Negotiations ensued between the two, about which we know sadly little. Was the savvy black marketeer played by the even savvier old woman, who could surely sense his mercenary motives? Did she drop hints about what might lie hidden somewhere inside the falling-down house? Maybe. Or maybe there was more mutual understanding and affection than that cynical interpretation allows for. At any rate, Corbu became a regular caller at the house, and on July 22, 1946, the two signed a contract. In it, Dénaraud gave the Villa Béthanie to Corbu outright, in return for a pledge from him that he would allow her to remain living there for the rest of her days.

If Corbu had signed the contract in the hope that Dénaraud would then let him in on some lucrative secret, that hope was frustrated soon after, when Dénaraud suffered a stroke which left her unable to speak. Corbu did find a substantial quantity of documents in the house: bills and work orders for the many construction and renovation projects, account books, legal records of Saunière’s difficulties with his bishop, even some personal journals. But none of it seemed to explain where his money had come from; nor did it have anything to say about any treasure that might still be hidden somewhere. If the Latin documents that had been found in the altar’s pillar were among the ones in the house, Corbu was not enough of a scholar to recognize them for what they were.

More years went by, during which the villa only grew more dilapidated. Dénaraud seldom poked her head out of doors, and Corbu too was rarely around, being engaged with business ventures that took him as far away as Morocco, where he made and just as quickly lost a small fortune in the sugar industry. In 1953, Marie Dénaraud died. She was buried next to Bérenger Saunière in the churchyard in accordance with the terms of her will, prompting a fresh round of tongue-wagging from the village old-timers.

Dénaraud’s death came shortly after Corbu’s Moroccan sugar disaster. Perhaps not coincidentally — on either point — he now began to take a serious commercial interest in her old residence for the very first time. He brought teams of workmen in to clean the place up, intending to turn it into a restaurant and hotel. But Corbu needed an angle compelling enough to make people drive up the twisting road that dead-ended here. He needed a reason to put Rennes-le-Château on the map, as it were. He turned to the same reason that had caused him to knock on Marie Dénaraud’s door for the first time eight years earlier. For if it had worked on him, he reasoned, it ought to work just as well on others.

He bought himself a tape recorder and recorded a précis of the strange case of Bérenger Saunière and his mysterious riches. His operative theory at this point was that the treasure Saunière had uncovered had once belonged to the French crown. In 1248, just a few years after the Cathar movement had been decapitated and the Languedoc incorporated firmly into the kingdom of France, King Louis IX had invaded Egypt at the head of the Seventh Crusade. He had left his mother, Blanche of Castile, to look after things in Paris while he was away. But the city had been plagued with unrest during this period, being stuffed to the gills with wayward noblemen who couldn’t see their way to being ruled by a woman. Corbu now concluded that Blanche must have emptied the royal treasury to keep it out of unfriendly hands, sending the whole kit and caboodle to the war-ravaged Languedoc, the part of the kingdom that was farthest from its capital in both geography and spirit. Who would think to look for it there? No one, it seemed, until Saunière had found some record of it hidden inside his church.

But in order to connect these two dots, Corbu had also to explain why the treasure had never been recalled to Paris after Louis IX had returned to the capital and things had settled down there. By way of doing so, he noted that Blanche had died in 1252, two years before her son’s return. (The hapless fellow had gotten himself captured by the Egyptians and spent four years as their hostage before he was ransomed.) Amidst the shuffle of regents and monarchs, the royal family had just plain forgotten where they’d put the treasure, in the same way that I can never figure out what drawer my wife has put the batteries in when she goes off to a conference and leaves me all alone at home.

It was a theory anyway. Corbu set great store by the fact that Philip IV, king of France from 1285 to 1314, had been infamously cash-poor, to the point of having to counterfeit money to keep his government from collapsing. Surely this was because silly Blanche had misplaced most of his inheritance a few decades earlier. No mention of the confusion appeared in any historical documents because the whole mess was just too embarrassing to talk about.

Based on no particular evidence, Corbu declared confidently that the royal treasure found by Saunière consisted of 18.5 million gold coins weighing 180 tons, plus countless jewels and religious objects; together it would be worth 4 billion francs in 1950s money. For all practical purposes, the store of wealth would have been inexhaustible. The primary purpose of Saunière’s many foreign trips had been to turn Medieval coinage into present-day francs, by melting the coins down and selling the lumps of raw metal that resulted. “A person from Carcassonne who is still alive assured me that he saw in the priest’s house a chest full of gold ingots,” Corbu insisted. Who could doubt such ironclad testimony?

In 1954, Corbu opened his restaurant. His taped story of Bérenger Saunière and the royal treasure was played to all of the diners during their meals. “Thus in this quiet village with its magnificent view and glorious past, there is one of the most fabulous treasures in the whole world,” he said at the end of the tape. Tell your friends! Don’t they deserve to bask in the mystery too?

The restaurant did well enough that Corbu could afford to convert the Tour Magdela into a hotel the following year. Meanwhile he continued to look for ways to get the word out to folks beyond the immediate vicinity of Rennes-le-Château. He hit pay dirt in January of 1956, when he lured in Albert Salamon, a journalist for the newspaper La Dépêche du Midi (“The South of France Dispatch”). Under the banner headline “The Fabulous Discovery of the Priest with Billions!”, Salamon laid it on thick. The trilogy of articles he wrote for his newspaper opens like a Gothic horror story, more Bram Stoker than Edward R. Murrow.

Dusk was advancing rapidly over the countryside as my friend’s cantankerous car carried us with steady rhythm along the steep winding road to the “high place” of Rennes-le-Château. At the top of the hill, the car was swallowed up among the centuries-old stones of an ancient queenly citadel, and then the tower appeared, a black shadow on the starry background.

The aim of the nighttime excursion? To answer an invitation to meet with M. Noël Corbu, founder and proprietor of the Hôtel de la Tour at Rennes-le-Château. I was eager to make the acquaintance of the brother of the test pilot Pierre Corbu, who died in 1927 with his comrade Lacoste on the Bluebird while he was trying for the third time to cross the Atlantic.

Mme. Corbu served us a meal of chicken, accompanied by fine wines. In the dining room, my curiosity was aroused by a portrait of a priest with a piercing gaze. “A relation, M. Corbu?”

A thick file was placed before me. The diary of the priest, plus hundreds of letters, bills, plans, estimates… and the story began.

These last words would prove true in a more all-encompassing way than Salamon could ever have dreamed at the time. For the media story of Rennes-le-Château really does begin precisely here. He was the first in a long line of credulous or calculating writers — the jury is still out for many of them — who have spun yarns around the little village that are as exciting and enticing as any avowedly fictional thriller. Seen in this light, it feels only fitting that the process culminated almost 50 years after Salamon’s articles in a bestselling, zeitgeist-defining novel and blockbuster movie.

For now, though, Salamon left the Villa Béthanie with a head stuffed full of mythical imaginings.

It is one o’clock in the morning. The ghosts that sat down at the host’s table in the course of this thrilling story have kept secret right to the end the mysterious hiding place whose “open sesame” the abbé had stumbled upon. And when the door of the Hôtel de la Tour was opened onto the night, and I held out my hand to M. Corbu in au revoir, there seemed to to be shining, where a moment ago there were stars, millions of golden pieces of the fabulous treasure…

It seems to have been the imagination of Salamon rather than the equally prodigious one of Corbu which added a new twist to the story, one that would become very important in the course of time. At the very end of his third and last article, Salamon mentioned the longstanding legends about “Cathar treasure, including the famous Holy Grail” being hidden somewhere in the Languedoc. Might it actually have been this treasure rather than that of the French crown that Saunière had stumbled upon? It did seem more plausible in some ways. Corbu too would gradually adopt this theory of the case.

Over the years that followed Salamon’s articles, Corbu’s Hôtel de la Tour marked the center of a slowly expanding circle of curiosity and greed. The phenomenon was nothing like what it would become, but it was sufficient to support a hospitality business in this rather far-flung location. The smoky air inside Corbu’s restaurant was filled with the speculations and arguments of mystics, cranks, and dreamers.

By 1960, the circle had expanded enough to reach the Parisian headquarters of the ORTF, France’s national broadcasting service. A film crew came to Rennes-le-Château to shoot a television documentary about the village and the mystery; these were quite possibly the first moving images ever captured in the place. The program aired throughout France in April of 1961, under the name of La Roue Tourne (“The Wheel Turns”). As far as I have been able to determine, only a single clip has survived, just 40 seconds in length. It reenacts of the discovery of the mysterious Latin documents inside a pillar next to the church’s altar. Corbu has gamely put on priestly vestments to play the role of Saunière as the documents are handed to him by a member of the work crew.

Outside of this clip, we have only a handful of newspapers reviews to fall back on. These serve to remind us that the more things change, the more they stay the same. One of them, which appeared in L’Indépendant, mentions a “hypnotist” cum treasure hunter named Domergue, who “based on the revelations of his medium, thinks that the famous treasure is actually contained in fourteen barrels, but that one of them has been emptied by the abbé. Even if only thirteen remain, however, their discovery would still cause a considerable stir around the marble escarpment of Rennes-le-Château.” (This is an understatement!) Our friend Domergue is sanguine about his prospects of success: “I’ll be resuming my excavations in June. I’m not very far away from my target, and before the end of the summer I’ll have reached the gallery leading to the barrels of gold.” The journalist chronicling all of this wonders, a little plaintively, “Will the secret and the mystery which surround the treasure be resolved one of these days?” The naïve fellow has no idea that “the secret and the mystery” are just getting off the ground.

The documentary caught the attention of at least one sober-minded historian as well. René Descadeillas had lived most of his 53 years in Carcassonne, whose municipal library he had headed since 1950. He knew the area’s past and present intimately. In December of 1962, he deposited into his library’s archives the results of a careful factual inquiry into Bérenger Saunière’s controversial tenure in Rennes-le-Château. In some ways, his investigation still stands as unique, in that it was undertaken early enough that some of the events in questions were still within living memory. Trolling through the documents of the period and interviewing witnesses and their descendants, he uncovered some interesting facts and testimony that cut against more fantastical interpretations of the case.

He learned, for example, that Saunière had already conducted some renovations of the church before 1891, for which he had paid the less than piddling sum of 518 francs, which was itself far beyond the means of his modest priestly stipend; he must, in other words, have had some alternative source of money even before the discovery of those Latin documents. Further, there were reports that Saunière had been explicitly asked by the village mayor what said documents were about, and had replied that they dealt strictly with technical details of the construction of the church. He could have been lying, of course, but his manner hadn’t struck anyone present at the time as particularly suspicious.

Descadeillas put forward a freshly prosaic explanation for Saunière’s sudden influx of cash after 1891, assuming he had been the beneficiary of one at all. It involved a windfall discovery of a sort, but one of a more modest scope and scale than our hypnotist friend’s fourteen barrels full of gold, much less Corbu’s 180 tons of the stuff. During the chaos of the French Revolution a century before Saunière’s arrival, when atheism had briefly become the order of the day throughout the country, an elderly village priest named Antoine Bigou was reported to have “buried his savings at the same time as the religious objects that he wished to preserve for the future.” As Descadeillas described it, “this was not a ‘treasure’ in the usual sense of the word, but a nest egg.” He actually talked to a still-living stepsister of Marie Dénaraud, who was “adamant” that Saunière had found “a pot of gold pieces” — but only the single pot — during the renovations of 1891. This fortuitous find could easily have planted the seed for the rumors of a lost treasure — rumors which would only grow in the telling, as such things inevitably do.

Still, the fact remained that such a comparatively modest quantity of gold couldn’t have paid for all of Saunière’s construction projects. Descadeillas strongly suspected that the rest of Saunière’s wealth came from criminal enterprises rather than from buried treasure. His younger brother Alfred had also been a priest, a known corrupt one who had gotten himself excommunicated in 1904 for stealing from his flock and fathering a child with one of them; he had then drunk himself to death the following year. An intriguing letter from Saunière to his lawyer described this brother as his “middle-man for generous deeds.” Descadeillas was convinced that one part of the brothers’ mutual activities had been “the selling of the Mass,” a way for people who were living less than righteous lives — such as gangland operators, perhaps? — to buy absolution for themselves; family members of the newly deceased unrighteous could likewise pay the priests to buy their relatives a ticket into Heaven. Descadeillas tracked down a postal worker in Couiza who remembered Saunière stopping in almost every day to pick up and deliver suspicious little envelopes — envelopes full, Descadeillas was certain, of money going one way and certificates of absolution going the other way. This sort of thing, known historically as the selling of “indulgences,” had once been accepted practice in the Catholic Church, had in fact been the proximate cause of Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation. Now, however, it was known as simony, one of the gravest sins which a member of the clergy could commit. The old story about the priest who went to deliver the Last Rites to Saunière, only to come out of the sickroom looking shocked to the very core of his being, suddenly made a lot more sense in this light.

But it seemed unlikely that even simony would have paid well enough to fit all of the facts of the case. The brothers must have been up to other sorts of corrupt dealings; of this Descadeillas was sure, even if he couldn’t prove it. He noted one more piece of circumstantial evidence: Saunière’s financial situation seemed to have taken a dive during the years after his brother’s death in 1905. He had funded little to no new construction after that point, and he had even had to take out a substantial bank loan in 1913 just to maintain his villa. Was this due to the loss of his “middle-man?” It seemed that he might truly have died as penniless as his will had claimed. The bank had finally forgiven the loan after Saunière’s death, when it decided that Marie Dénaraud had no realistic means of paying it back. Bankers usually have a sense about such things.

Much remained unexplained, but Descadeillas believed that the explanations, should they ever come, would prove to have more to do with everyday corruption and criminality than any centuries-old treasure trove. “The treasure of Rennes does not exist,” he wrote in conclusion. “But the secret of the priest of Rennes is real. And it is there that the mystery resides.”

All of this was perfectly reasonable and sensible, but it was always going to be doomed to have a tough time competing against tales of a grandiose Cathar treasures hoard. It didn’t help that René Descadeillas was a quiet, scholarly man by nature, content to write his report, drop it into his library’s archive for posterity, and move on to the next project. No film crews came around to get his side of the case. That said, we haven’t heard the last of Descadeillas, a rare and therefore invaluable voice of reason in the story of Rennes-le-Château.

For the time being, though, life went on as usual at the Villa Béthanie. The treasure hunters streamed through, each of them leaving empty-handed but full of new esoteric theories about where to dig next time. They became a nuisance for the local landowners, who were constantly finding new holes in the most likely and unlikely of places, as if their holdings had been infested by giant moles. In 1965, the municipal government issued a decree: no more excavations allowed without a permit. That helped somewhat, but the most dedicated seekers just took to digging under the cover of night. It was more atmospheric at night anyway.

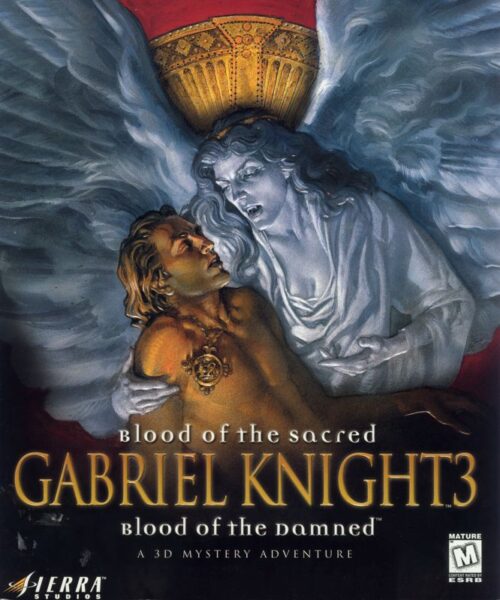

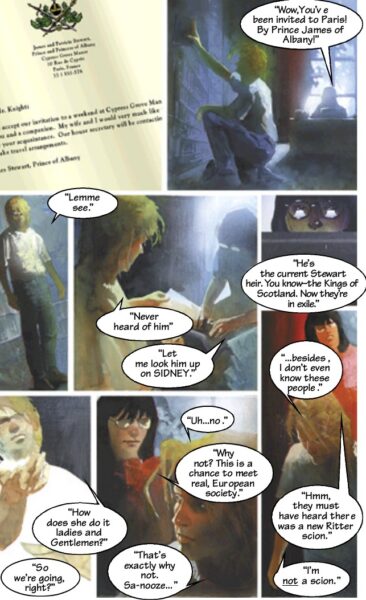

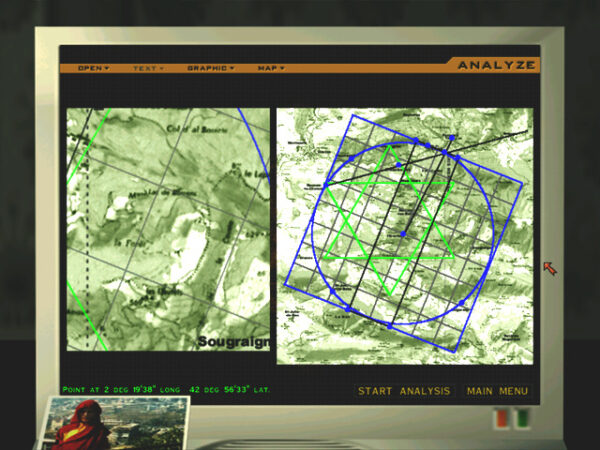

Gabriel Knight 3′s Aussie treasure hunter John Wilkes, who takes an elaborate high-tech approach to the search, is of a type well-known to the locals around Rennes-le-Château. In the 1960s, metal detectors, Geiger counters, and dousing rods were the tools of choice, but the spirit remained the same.

That same year, Noël Corbu sold the Villa Béthanie to a man named Henri Buthion. Restless serial entrepreneur that he was, Corbu had set up a side business making ladies’ fans and lampshades in the villa’s orangery. It was going pretty well; he wanted to expand it, but there just wasn’t enough space to do so in such a little village. Meanwhile much of the fun of running a hotel and keeping the mystery of Bérenger Saunière alive through year after year in which nothing concrete was discovered had run its course for him and his wife. So, he sold out and went on to the next adventure. Sadly, though, the adventure of life was almost over for him: he was killed in a car accident in 1968.

But the ball that Corbu had set rolling now had an unstoppable momentum of its own. Buthion continued to run the Hôtel de la Tour pretty much as his predecessor had, albeit with slightly less dramatic flair. He would be the witness and benefactor rather than the instigator of the next chapter of the saga of Saunière’s treasure. The whole thing was about to get a massive injection of plot inflation from a couple of new voices on the scene. This shit was about to get a whole lot weirder.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Holy Blood, Holy Grail by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln; Bloodline of the Holy Grail: The Hidden Lineage of Jesus Revealed by Laurence Gardner; The Treasure of Rennes-le-Château: A Mystery Solved by Bill Putnam and John Edwin Wood; The Holy Grail: The History of a Legend by Richard Barber; Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-religions by Ronald H. Fritze; The Tomb of God: The Body of Jesus and the Solution to a 2,000-Year-Old Mystery by Richard Andrews and Paul Schellenberger; Rennes-le-Château et l’enigme de l’or maudit by Jean Markale. Skeptical Inquirer of November/December 2004; La Dépêche du Midi of January 12, 13, and 14 1956; L’Indépendant of April 22 1961.

Online sources include the websites Rennes-le-Château: Where History Meets Evidence and Priory of Sion.com