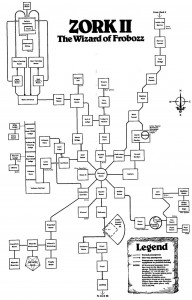

We left off last time with the Alice area at the top of the well. Let’s continue now with the rooms that sprawl around the Carousel Room, which are now much easier to get to since we’ve stopped the carousel’s rotation by switching it off from the Machine Room.

In the Dreary Room off to the north is the first recorded instance of a venerable adventure-gaming cliché: a locked door with a key in the keyhole on the other side. What follows would quickly become a pretty rote procedure for seasoned adventurers, almost like a maze, but taken without all of the baggage of games to come it’s a fresh and clever puzzle.

>PUT MAT UNDER DOOR

THE PLACE MAT FITS EASILY UNDER THE

DOOR.

>PUT OPENER IN KEYHOLE

THE LID IS IN THE WAY.

>OPEN LID

THE LID IS NOW OPEN.

>PUT OPENER IN KEYHOLE

THERE IS A FAINT NOISE FROM BEHIND THE

DOOR AND A SMALL CLOUD OF DUST RISES

FROM BENEATH IT.

DONE.

>GET MAT

AS THE PLACE MAT IS MOVED, A RUSTY IRON

KEY FALLS FROM IT AND ONTO THE FLOOR.

>GET KEY

TAKEN.

This puzzle was also present in the PDP-10 Zork; thus my relative confidence in proclaiming it the first of its kind. Interestingly, in the original game the mat that was needed was the welcome mat found all the way back outside the front door to the white house. In the PC version Lebling instead placed a handy place mat in the gazebo alongside the U.S. News and Dungeon Report.

There’s also a dragon underground, the slaying of which is a tricky but not untenable puzzle. The dragon was holding a princess captive — a princess who can retrieve a key from a certain unicorn back in the garden, solving a problem that has been frustrating us since we first wandered in. The game subtly but effectively cues us that we need something from her, and that we should be following her.

>EXAMINE WOMAN

THE PRINCESS (FOR SHE IS OBVIOUSLY ONE)

SHAKES HERSELF AWAKE, THEN NOTICES YOU

FOR THE FIRST TIME. SHE SMILES. "THANK

YOU FOR RESCUING ME FROM THAT HORRID

WORM," SHE SAYS. "I MUST DEPART. MY

PARENTS WILL BE WORRIED ABOUT ME." WITH

THAT, SHE ARISES, LOOKING PURPOSEFULLY

OUT OF THE LAIR.

>OPEN CHEST

THE HINGES ARE VERY RUSTY, BUT THEY SEEM

TO BE STARTING TO GIVE. YOU CAN PROBABLY

OPEN IT IF YOU TRY AGAIN. THERE IS

SOMETHING BUMPING AROUND INSIDE. ALL

THIS RUMMAGING AROUND HAS STARTLED THE

YOUNG WOMAN.

THE PRINCESS IGNORES YOU. SHE LOOKS

ABOUT THE ROOM, BUT HER EYES FIX ON THE

SOUTH.

THE PRINCESS WALKS SOUTH. SHE GLANCES

BACK AT YOU AS SHE GOES.

>S

DRAGON ROOM

THERE IS A DISHEVELLED AND SLIGHTLY

UNKEMPT PRINCESS HERE.

THE PRINCESS WALKS EAST. SHE GLANCES

BACK AT YOU AS SHE GOES.

>E

It’s another puzzle that needs that little nudge… no, wait, this puzzle has that little nudge. If only they were all this way…

But enough with good puzzles. Let’s talk about the first of Zork II‘s two legendarily bad ones: the Bank of Zork. In his review of the game on IFDB, Peter Pears actually called this puzzle “beautiful.” In a way I can see what he means, but for me it’s undone once again by a lack of sufficient cues as well as a lack of feedback and parser difficulties. The bank consists of several rooms, but the heart of it is the Safety Depository.

SAFETY DEPOSITORY

THIS IS A LARGE RECTANGULAR ROOM. THE

EAST AND WEST WALLS HERE WERE USED FOR

STORING SAFETY DEPOSIT BOXES. AS MIGHT

BE EXPECTED, ALL HAVE BEEN CAREFULLY

REMOVED BY EVIL PERSONS. TO THE EAST,

WEST, AND SOUTH OF THE ROOM ARE LARGE

DOORWAYS. THE NORTHERN "WALL" OF THE

ROOM IS A SHIMMERING CURTAIN OF LIGHT.

IN THE CENTER OF THE ROOM IS A LARGE

STONE CUBE, ABOUT 10 FEET ON A SIDE.

ENGRAVED ON THE SIDE OF THE CUBE IS SOME

LETTERING.

ON THE GROUND IS A SMALL, WORN PIECE OF

PAPER.

As you might expect, that “curtain of light” is actually another exit. However, we can’t go that way simply by typing “N.” That just leads to, “THERE IS A CURTAIN OF LIGHT THERE,” which is in turn likely to lead us to give up on that direction of inquiry. Yet it turns out we can “ENTER CURTAIN.” Similar parser problems dog us at every stage in the bank, but even they aren’t the worst of it. To make a long and convoluted puzzle short, the place where we go after entering the curtain of light is dictated by the direction we last came from before entering. This is never explained or even hinted at at any point, and it’s obviously a very subtle and tenuous connection to make. Most players who “solved” the Bank of Zork did so only through sheer persistence, moving everywhere and trying everything, and were left with no idea of what they had actually done or how the puzzle really worked. Like Zork II‘s other notorious puzzle (of which more in a moment), the Bank of Zork specifically informed an entry in Graham Nelson’s “Player’s Bill of Rights”: the player should “be able to understand a problem once it is solved.”

Next we explore the volcano area to the west, which we accomplish largely via a hot-air balloon. Many of the puzzles and situations in Zork were designed around the capabilities of the technology used to create the games. Having created the programming for vehicles once for the boat found back in Zork I, the designers continued to use it again and again. Like the well, the balloon puzzle first involves deducing what it — “A LARGE AND EXTREMELY HEAVY WICKER BASKET” with “A RECEPTACLE OF SOME KIND” in the center and “AN ENORMOUS CLOTH BAG DRAPED OVER THE SIDE” — actually is. We need to burn something, like the U.S. News and Dungeon Report, in the receptacle to inflate the bag. The idea that burning something as small as a newspaper could do the trick doesn’t make a whole lot of sense in the real world, but adventure games have always had physics all their own, as Duncan Stevens and I briefly discussed in the comments section of my last post. Of more immediate concern are the parser frustrations that once again make this puzzle more difficult than it was likely designed to be.

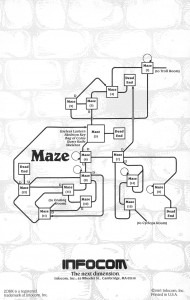

And so we come to the Oddly-Angled Room, better known as the infamous baseball maze. At first it appears to be a conventional maze, but we soon realize that it defies all attempts to map it. Every connection is literally random, changing constantly according to no rhyme or reason. The diamond-shaped windows in the floor of each room don’t seem to offer much help. The key clue is the “club” we find:

A LONG WOODEN CLUB LIES ON THE GROUND

NEAR THE DIAMOND-SHAPED WINDOW. THE CLUB

IS CURIOUSLY BURNED AT THE THICK END.

>GET CLUB

TAKEN.

>EXAMINE CLUB

THE WORDS "BABE FLATHEAD" ARE BURNED

INTO THE WOOD.

We’re expected to “run the bases”, moving diagonally through the rooms starting from home plate, which is located at the west end of the “ballpark”: southeast, northeast, northwest, southwest. The windows give us a slight clue when we are on the right track, lighting up more strongly for each correct movement we make. Even so, this is all deeply problematic on a couple of levels. Firstly, Zork eventually spread well beyond the United States, to players who had no clue about the game of baseball, inspiring the most amusingly specific of all Nelson’s Player’s Rights: a player should “not need to be American to understand hints.” But of course, even many Americans aren’t interested in baseball at all and know next to nothing about it. This right could be better rewritten as a prohibition on requiring any sort of esoteric or domain-specific outside knowledge. Yet the puzzle is even dodgy for someone like me, who loves baseball. From what I can see, there is no way to deduce that home plate in this particular ballpark is located at its western side, and thus no way to know which way to go in running the bases, at least outside of the extremely, shall we say, subtle cues offered by the windows. The baseball maze wasn’t in the PDP-10 Zork, but was devised by Lebling specifically for the PC version. He’s repeatedly apologized for it over the years since, noting that it stemmed from his boredom with mazes and desire to do something different with the general idea. Needless to say, we’d have been better off with a standard maze.

Up to this point we’ve been amassing treasures and scoring points for collecting them, but, unlike in Zork I, we’ve found no obvious thing to do with them. In the PDP-10 version, these treasures were simply more loot to be collected in the white house’s trophy case. In this game, of course, that’s not possible, what with the barrow having sealed itself behind us and the white house consigned to Zork I. The most obvious solution to this problem would have been to just give us another trophy case somewhere. That’s not, however, what Lebling chose to do. Instead he decided to devise an actual purpose for our collection beyond looting for looting’s (and points’) sake. Like other elements of Zork II, the need to restructure things for practical reasons here led Lebling to take a step in the direction of story.

Now, late in the game, we penetrate the Wizard’s inner sanctum at last. Amongst other fun and puzzles, we can summon a demon here by making use of the three magic spheres we’ve collected earlier — the one in the Alice area which the robot helped us to collect, the one behind the locked door in the Dreary Room, and one which we find in the aquarium inside the wizard’s inner sanctum itself. But demons, of course, don’t work for free. To do us a favor, he demands payment in the form of ten treasures. Yes, it’s all very pat and convenient, but combined with other innovations like the Wizard himself it gives Zork II a shred of plotting and motivation that both Zork I and the PDP-10 Zork lack. Count it as a step on Infocom’s road from text adventures to interactive fiction.

Once the demon is satisfied, we have a favor at our disposal. Unfortunately, it’s easy neither to figure out what that favor should be nor how we should go about asking for it. If we manage both, though, we’re greeted with this:

>SAY TO DEMON "GIVE ME WAND"

"I HEAR AND OBEY!" SAYS THE DEMON. HE

STRETCHES OUT AN ENORMOUS HAND TOWARDS

THE WAND. THE WIZARD IS UNSURE WHAT TO

DO, POINTING IT THREATENINGLY AT THE

DEMON, THEN AT YOU. "FUDGE!" HE CRIES,

BUT ASIDE FROM A STRONG ODOR OF

CHOCOLATE IN THE AIR, THERE IS NO

EFFECT. THE DEMON PLUCKS THE WAND OUT OF

HIS HAND (IT'S ABOUT TOOTHPICK SIZE TO

HIM) AND GINGERLY LAYS IT ON THE GROUND

BEFORE YOU. HE FADES INTO THE SMOKE,

WHICH DISPERSES. THE WIZARD RUNS FROM

THE ROOM IN TERROR.

And so the tables are turned. I feel a little bit sorry for the poor fellow. He seems more playfully insane than evil. But then again, I feel sorry for a lot of the monsters I have to kill in Wizardry, so count me as just a big softie.

We now have a magic wand at our disposal — a very cool thing. The immediate temptation is to go around waving it at anything and everything, trying out each of the Wizard’s arsenal of spells. Yet for inexplicable in-story reasons but all too explicable technical reasons, only one actually works: Float, which lifts a boulder for us to unblock an entrance in the Menhir Room and retrieve a final key item. I particularly wanted to spell a certain three-headed guard dog in the Cerberus Room, but, alas, my efforts to Ferment, Freeze, and even Filch the hound proved in vain. Only Float gave any sort of appropriate response at all: “THE HUGE DOG RISES ABOUT AN INCH OFF THE GROUND, FOR A MOMENT.” If the implementation here is kind of sketchy, the idea of having a collection of spells at one’s disposal is still a very compelling one, and one that obviously remained with Lebling and his colleagues: they would later produce a trilogy of games that revolved around that very mechanic.

We now make our way into the final room of the game, the crypt. We also now have all 400 points — and yet the game doesn’t end. We in fact have one final puzzle to solve. We need to extinguish the lantern within the crypt, using some grue repellent we found lying around to protect ourselves. In the darkness we can see the “FAINT OUTLINE” of a “VERY TIGHT DOOR,” the way forward into Zork III. It’s yet one final example of a clever little puzzle that just needed a little bit more of a nudge; the solution is arguably hinted at, but much earlier in the game, and so subtly it’s almost impossible not to overlook. For the really unlucky, the game here also unveils its nastiest trick of all. One of the spells the Wizard — luckily, seemingly very rarely — casts is Fluoresce, which causes one to glow with light, apparently in perpetuity. What a lucky break, one thinks; no more worrying about that expiring lantern! Until, of course, one comes here and can’t finish the game. Infocom may have been making them better than anyone else already, but they were still making them pretty damn cruel at times.

But that’s Zork II for you — more sophisticated technically and thematically than its predecessor, but also with more design issues and a wider mean streak. Of course, in evaluating works we always have to be mindful of the milieu that created them. Adventure games in 1981 were cruel and difficult as a matter of course. Infocom in the years to come would be largely responsible for showing that they could succeed as art and challenge as games without hating their players, but they weren’t quite there yet. Likewise, they would show that they could be about more than treasures, puzzles, and points, but Zork II merely nods in that direction rather than striding down that road with purpose. Neither a masterpiece nor an outright failure, Zork II stands as an important way-station rather than a definitive landmark.

Still, those looking for a game changer should just stick around. Infocom’s next release would not completely sort out the adventure-game design issues I’ve been harping on about for many posts now, but it would completely upend the traditional definition of what an adventure game was and what it could do.