The user-interface constructs that are being developed in computer games are absolutely critical to the advancement of digital culture, as much as it might seem heretical to locate the advancement of civilization in game play. Now, yes, if I thought my worth as a person would be judged in the next century by the body counts I amassed in virtual-fighting games, I guess I’d be worried and dismayed. But if the question is whether a wired world can be serious about art, whether the dynamics of interactive media’s engagement can provide a cultural experience, I think it’s silly to argue that there are inherent reasons why it cannot.

— Michael Nash

The career arc of Michael Nash between 1991 and 1997 is a microcosm of the boom and bust of non-networked “multimedia computing” as a consumer-oriented proposition. The former art critic was working as a curator at the Long Beach Museum of Art when Bob Stein, founder of The Voyager Company, saw some of the cutting-edge mixed-media exhibitions he was putting together and asked him to come work for him. Nash jumped at the chance, which he saw as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to become a curator on a much grander scale.

I was very interested in TV innovators like Ernie Kovacs and Andy Kaufman, in the development of music videos, and in the work of artists using the computer. [I believed] that opportunities can open up for artists at key times in the history of media — artists dream up the kinds of possibilities that push media to envision new things before the significance of these things is generally understood. “Where do you want to go today?” the [technical] architects of the new media ask, because they don’t know. They’re waiting for some great vision to make all this abstract possibility into compelling experiences that will provide shape, purpose, and direction. The potential of the new media to express cultural ideas has increased much faster than the development of new cultural ideas, so the potential is there.

Michael Nash’s official title at Voyager was that of Director of the Criterion Collection, the company’s line of classic films on laser disc — also its one reliably profitable endeavor, the funding engine that powered all of Bob Stein’s more esoteric experiments in interactive multimedia. But roles were fluid at Voyager. “It felt like a lair of tech-enamored bohemians,” remembers Nash. “The company style was 1970s laid-back mixed with intense intellectual ferment and communalism. The work environment was frenetic, at times even a little chaotic.”

As the hype around multimedia reached a fever pitch, everyone who was anyone seemed to want a piece of Voyager. In a typical week, the receptionist might field phone calls from rock star David Bowie, from thriller author Michael Crichton, from counterculture guru Timothy Leary, from cognitive scientist Donald Norman, from Apple CEO John Sculley, from computer scientist Alan Kay, from particle physicist Murray Gell-Mann, from evolutionary biologist Steven Jay Gould, from classical cellist Yo Yo Ma, and from film critic Roger Ebert. The star power on the production side of the equation dwarfed the modest sales of Voyager’s CD-ROMs almost to the point of absurdity. (Only two Voyager CD-ROMs would ever crack 100,000 units in total sales, while most failed to manage even 10,000.)

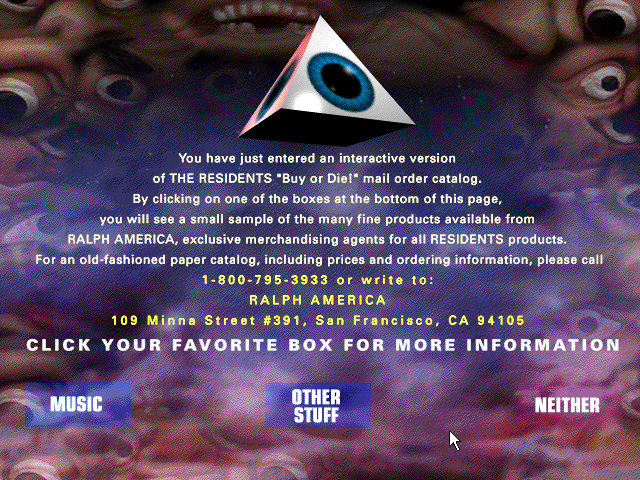

Another of the stars who wound up working with Voyager — a star after a fashion, anyway — was the Residents, a still-extant San Francisco-based collective of musicians and avant-garde conceptual artists whose members have remained anonymous to this day; they dress in disguises whenever they perform live. Delighting in the obliteration of all boundaries of bourgeois good taste, the Residents both deconstruct existing popular music — their infamous 1976 album The Third Reich n’ Roll, for example, re-contextualized dozens of classic postwar hits as Hitler Youth anthems — and perform their own bizarre original songs. Sometimes it’s difficult to know which is which; their 1979 album Eskimo, for instance, purported to be a collection of Inuit folk songs, but was really a put-on from first to last.

During the 1980s, the Residents began to make the visual element of their performances as important as the music, creating some of the most elaborate concert spectacles this side of Pink Floyd. The term “multimedia” had actually enjoyed its first cultural vogue as a label for just this sort of performance, after it was applied to the Exploding Plastic Inevitable shows put on by Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground in 1966 and 1967. Thus it was rather appropriate for the Residents to embrace the new, digital definition of multimedia when the time came. It was Michael Nash who made the deal to turn the Residents’ 1991 album Freak Show, a song cycle about the lives and loves of a group of circus freaks, into a 1994 Voyager CD-ROM. Nash:

Within alienage, we discover a lot about the paradox of our own alienation. The recognition of difference is the way we establish our identity and the uniqueness of our own point of view. We are drawn to extreme kinds of “alien” identity — freak shows, fanatics, psychotics, serial killers, nightmares, monsters from outer space — because we are fascinated by absolute otherness, lying as it does at the heart of our own sense of self. We never tire of this paradox because it is so charged by opposites: quirky, eccentric, weird, dark, transgressive vision is so different from our own and yet so full of the very thing that makes us different, that gives our identity its integrity. I think it’s a powerful dynamic to draw on in establishing the essential attributes of extraordinary inner realms that distinguish the best work in the field.

Critics of the capitalistic system though they were, the Residents weren’t above using the Freak Show CD-ROM to sell some other merch — in a suitably ironic way, of course.

Personally, I find the sentiment above — and the tortured grad-school diction in which it’s couched — to be something the best artists grow out of, just as I find raw honesty to produce a higher form of art than the likes of the Residents’ onion of off-putting artificiality and provocation for the sake of it. Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks, the obvious inspiration for the Residents’ album and the CD-ROM, offers a more empathetic, compassionate glimpse of circus “aliens” in my opinion. But to each his own: there’s no question that Freak Show was another bold statement from Voyager that interactive CD-ROMs could and should deal with any and all imaginable subject matter.

The same year that Freak Show was released, Michael Nash left Voyager to set up his own multimedia publisher. Freak Show had been one of the few Voyager discs that could be reasonably labeled a game. Now, Nash wanted to move further in that direction with the company he called Inscape. In a testament to both the tenor of the times and his own considerable charisma, HBO and Warner Music Group agreed to invest $2.5 million each in the venture. Any number of existing games publishers would have killed for a nest egg such as that.

But then, Inscape and Michael Nash himself were the polar opposite of all existing stereotypes about computer games. Certainly the dapper, well-spoken Nash could hardly have been less like the scruffy young men of id Software, those makers of DOOM, the biggest hardcore-gaming sensation of the year. The id boys were just the latest of the long line of literal or metaphorical bedroom programmers who had built the games industry as it currently existed, young men who played games and obsessed over the inner workings of the computers that ran them almost to the exclusion of all the rest of life’s rich pageant. Nash, on the other hand, was steeped in a broader, more aesthetically nuanced tradition of arts and humanities, and knew almost nothing about the games that had come before the multimedia boom he found so bracing. In an ideal world, each might have learned from the other: Nash might have pushed the existing game studios to mine some of the rich veins of culture beyond epic fantasy and action-movie science fiction, and they in their turn might have taught Nash how to make good games that made you want to keep coming back to them. In the real world, however, the two camps mostly just sniped snidely at one another — when, that is, they deigned to acknowledge one another’s existence at all. Nash was too busy beating the drum for “radical alternative subversive perspectives, what I call transgressive work” to think much about the more grounded, sober craft of good game design.

Most of Inscape’s output, then, is all too typical of such an entity in such an era. The Residents stayed loyal to Nash after he left Voyager, and helped Inscape to make Bad Day on the Midway, another, modestly more ambitious take on the lives of circus freaks. Meanwhile Nash, who seemed to have a special affinity for avant-garde rock music, also joined forces with the only slightly less subversive but much more commercially successful collective known as Devo — in a reflection of their shared sensibilities, both Devo and the Residents had once recorded radically deconstructed versions of the Rolling Stones classic “Satisfaction” — to make something called Adventures of the Smart Patrol. Such works garnered some degree of praise in their time from organs of higher culture who were determined to see that which they most wished to see in them; writing for The Atlantic, Ralph Lombreglia went so far as to call Smart Patrol “the CD-ROM equivalent of Terry Gilliam’s remarkable film Brazil.” Those who encounter these and other, similar rock-star vanity projects today, from artists as diverse as Prince and Peter Gabriel, are more likely to choose adjectives like “aimless” and “tedious.” (“Will we look back in nostalgia on such titles as Bad Day on the Midway and Adventures of the Smart Patrol?” asked Lombreglia in his 1997 article, which was already mourning the end of the multimedia boom. Well, I’m from the future, Ralph… and no, we really don’t.)

It seems to me that the discipline of game design has often suffered from the same fallacy that dogs writing: the assumption that, because virtually everyone can design a game on some literal level, the gulf between bad and good design is easily bridged, with no special skills or experience required. Most of the products of Inscape and their direct competitors serve as cogent examples of where that fallacy — and its associated disinterest in the process that leads to compelling interactivity, from the concept to the testing phase — can lead you.

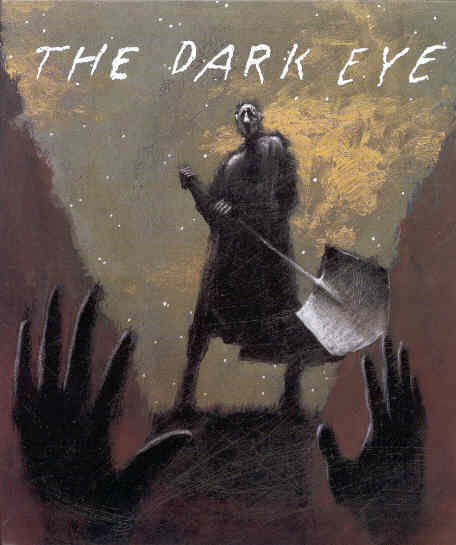

In the case of Inscape, however, there is one blessed exception to the rule of trendy multimedia mediocrity. And it’s to that exception, which is known as The Dark Eye, that I’d like to devote the rest of this article.

The Dark Eye was Inscape’s very first game, released in late 1995. It’s an interactive exploration of the macabre world of Edgar Allan Poe — not a particularly easy thing to pull off, which explains why games that use Poe’s writings as a direct inspiration are so rare. When we do encounter traces of him in games, it’s generally through the filter of H.P. Lovecraft, the longstanding poet laureate of ludic horror, who himself acknowledged Poe as his most important literary influence. But Poe, whose short, generally unhappy life ended in 1849, was a vastly better, subtler writer than his twentieth-century disciple, with both a more variegated and empathetic emotional range and an ear for language that utterly eluded him. While Poe can occasionally lapse into Lovecraftian turgidity in prose, his poetry is almost uniformly magnificent; works like “The Bells” and “Annabel Lee” positively swing with a musical rhythm that belies his popular reputation as a parched, unremittingly dour soul. Like so much of the best writing, they beg to be read aloud.

The problem with adapting Poe’s stories into a computer game — or into a movie, for that matter — is that their action, such as it is, is so internal. Their narrators, who are generally mentally disturbed if not outright insane and therefore thoroughly unreliable, are always their most fascinating characters. Their stories are constructed as epistles to us the readers; we learn of their protagonists not through dialog or their actions in the physical world, but through the words they write directly to us, explaining themselves to us. Without this dimension, the stories would be fairly banal tales of misfortune and mayhem, pulp rather than fine literature.

Bringing the spirit of Edgar Allan Poe to life on the computer, then, requires getting beyond the realm of the literal in which most digital games exist. It requires an affinity for subtlety and symbolism, and a fearless willingness to deploy them in a medium not terribly known for such things. Fortunately, Michael Nash had a person with just such qualities to hand, in the form of one Russell Lees.

In 1994, Lees was an electrical engineer and aspiring playwright who had little interest in or experience with computer games. But then Nash, a “friend of a friend,” happened to show him Freak Show. He found it endlessly intriguing, and was in fact so enthusiastic that Nash suggested he send him a list of possible projects he might like to make for this new venture called Inscape. One of the suggestions Lees came up with was, he remembers, “dropping into the tales of Poe.” Only after Nash gave the Poe project the green light and Lees found himself suddenly thrust into the unlikely role of game designer did the difficulties inherent in such an endeavor dawn on him: “What have I done? Dropping into the tales of Poe? What does that mean? It’s a completely nonsensical sentence!”

Lees and Inscape eventually decided to present three Poe stories in an interactive format, along with an original tale in his spirit that would serve as a jumping-off and landing place for the player’s explorations of the master’s works. Two of the trio, “The Tell-tale Heart” and “The Cask of Amontillado,” are among Poe’s most famous works of all, the stuff of English-language high-school curricula for time immemorial; the other, “Berenice,” is less commonly read, but is if you ask me the most disturbing of the lot. All are intimate tales of psychological obsession and, in two cases, murder. (“Berenice” settles for necrophilia in its stead…)

The game begins with you knocking on the door of your uncle’s house. Once inside, your casual family visit takes on a more serious dimension, when you become the reluctant go-between in a love affair between your beautiful young cousin and your brother — a love affair of which your uncle most definitely does not approve. (The relationship is a presumably deliberate echo of Poe’s courtship and marriage to his own thirteen-year-old cousin Virginia Clemm, whose long, slow death from tuberculosis became the defining event of his life, the catalyst for his final descent into alcoholism, despair, and at last the sweet release of death.) As this frame story plays out, you’re periodically plunged into nightmares and hallucinations in which you enact Poe’s tales. In fact, you enact each of them twice: once in the role of the aggressor, once in that of the victim.

Through it all, The Dark Eye shows the unmistakable influence of the adventure games that other studios were making at the time. The creepily expressive human hand it uses for a mouse cursor, for example, is blatantly stolen from The 7th Guest. But the more pervasive model is Myst. The Dark Eye‘s node-based navigation through contiguous environments, first-person viewpoint, and minimalist, inventory-less interface are obvious legacies of Myst. The technologies behind it as well are the same as Myst: a middleware presentation engine (Macromedia Director in this case), 3D modelers, QuickTime movie clips, all far removed from the heavily optimized bare-metal code which powered games like DOOM (and thus one more reason for fans and programmers of games like that one to hold this one in contempt).

Likewise, all four of the stories that make up The Dark Eye engage in a style of environmental storytelling — or, perhaps better said, backstory-revealing — that will on one level be familiar to players of Myst and its many heirs. And yet it serves a markedly different agenda here. The character you played in Myst was you or whomever else you chose to imagine her to be, a blank slate wandering an alternate multiverse. Not so in The Dark Eye. Lees:

I think coming from a theater background influenced how I thought about it. In my head, “dropping into the tales of Poe” is only interesting if you drop into a character: if you drop into some character’s head. We’re asking the player to not play themself. In many games, the whole idea is that the player gets to be themself, with all kinds of freedom. If you’re playing Grand Theft Auto, you’re you, but a different version of you who can steal cars.

We weren’t interested in that at all. What we were interested in was… you drop into a character, and basically you’re an actor trying to play that character. What does that mean? If you’re a real actor playing the narrator in “The Tell-tale Heart,” for example, you would read through [the script], come up with some backstory for the character, try to flesh the character out so that every line in the performance resonates with a life lived. As the player, you’re not going to get that. So, how do we make up for that in an interactive situation? The way we solved it — and I feel like we did solve it, in fact — was this:

We tried to map that psychological investigation that an actor would bring to a part onto spatial investigation. You’re exploring a space where certain objects have importance to you. It’s not just, I pick up a letter and learn about my character [by reading it]. It’s, I pick up an object that’s important to my character and I hear my character thinking about it, or that object triggers a movie where I see something from my character’s past, or maybe it just plays a little bit of music. So, all these objects are imbued with something from your past. We were trying to “trick” the player into doing a psychological investigation of the part they were playing.

The Dark Eye is interested in enriching your experience of the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, not in giving you a way of changing them; you can’t choose not to plunge the knife into the old man who is murdered in “The Tell-tale Heart.” But you can inhabit the story and the characters in a way interestingly different from, if not necessarily superior to, the way you can understand them through the pages of a book. The best compliment I can give to Russell Lees is that the framing story and the three Poe narratives from the perspective of the victims feel thoroughly of a piece with the three more familiar stories and perspectives. It’s no trivial feat to expand upon the work of a literary master so seamlessly.

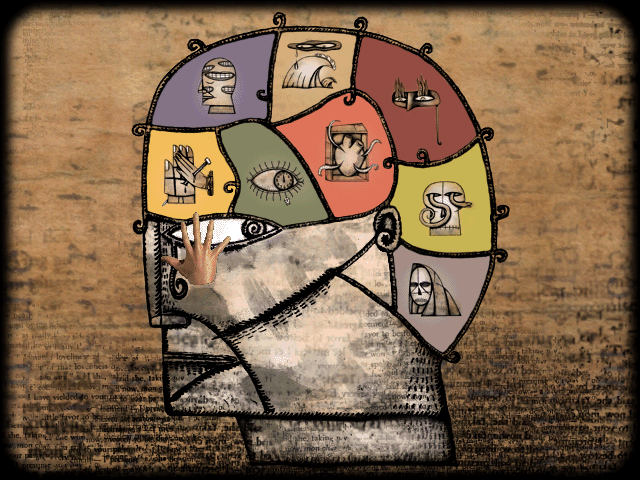

The Dark Eye employs many tricks to evoke Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic nineteenth-century world. As you uncover more story segments, for example, you can return to them from this screen. It’s based upon the pseudo-science of phrenology, of which Poe, like many of his peers, was a great devotee. (“The forehead is broad, with prominent organs of ideality,” he wrote in a typical reference to it, in an 1846 character sketch of his fellow poet William Cullen Bryant.)

“The Tell-tale Heart”

“The Cask of Amontillado”

“Berenice”

Like so many of gaming’s more esoteric art projects, The Dark Eye is a polarizing creation. Some people love it, while others greet it with a veritable rage that seems entirely out of proportion to such a humble relic of a bygone age. It rams smack into one of the fundamental tensions that have dogged adventure games as long as they have existed. Ought you to be playing yourself in these games, or is it acceptable to be asked to play the role of someone else, perhaps even someone you would never wish to be in real life? The question was first thrashed over in the gaming press in 1983, when Infocom released Infidel, a text adventure whose fleshed-out protagonist was almost as unpleasant as a Poe narrator. It has continued to raise its head from time to time ever since.

But there’s even more to the polarization than that. It seems to me that The Dark Eye divides the waters so because, although it bears many of the surface trappings of a traditional adventure game, its goals are ultimately different. While a game like Myst is built around its puzzles, The Dark Eye has quite literally no puzzles at all. In fact, admits Russell Lees, freely acknowledging the worst of the criticism leveled against it, it has “no gameplay beyond exploration.” You don’t “beat” The Dark Eye, in other words; you explore it. More specifically, you explore its characters’ interior spaces. Watching many gamers engage with it is akin to watching fans of genre fiction confronted with a literary novel, except that here “where’s the puzzles?” stands in for “where’s the plot?” This is not to say that those who appreciate The Dark Eye are better, more refined souls than those who find it aimless and tedious, any more than those who enjoy John Steinbeck are superior to readers of John Grisham. It’s just to say that clashes of expectation can be difficult things to overcome. “We need some new words for works that are interactive but aren’t so much games,” says Lees — a noble if hopeless proposition.

We can see these things play out in the reaction to The Dark Eye from the gaming press after its release. Most reviewers just didn’t know what to do with it. The always articulate Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World reacted somewhat typically:

As with many of the new “exploration” adventure games, the environment reeks of emptiness, especially at first. But it’s worse here than in most: not only are there too many empty rooms, but you aren’t asked to solve puzzles of any sort, not even the lame brainteasers most games use as filler. Making matters worse, there are hallways you see that, for no apparent reason, the computer doesn’t let you go down; doors the game doesn’t let you open; and characters the game doesn’t let you click on. Even the few objects you run across — a meat cleaver, a paper knife — the game doesn’t let you take.

But, because he is a thoughtful if not infallible critic, Ardai must also acknowledge The Dark Eye to be “a singular, disturbing vision equal to the task of rendering Poe’s nightmare worlds.” He even calls it “brave.”

Instead of puzzles, The Dark Eye gives you atmosphere — all the atmosphere you can inhale, enough atmosphere to send you running to a less pressurized room of your house after spending a while in its company. You witness no actual violence on the screen; the camera always cuts away at the pivotal moment. Yet the game is thoroughly unnerving, more psychologically oppressive than a thousand everyday videogame zombies; this game will creep you the hell out. It’s in vacant eyes of the stop-motion-animated digitized puppets that are used to represent the other characters; in the way that the soundtrack, provided by associates of avant-rock musician Thomas Dolby, suddenly swells with nerve-jangling ferocity and then fades into silence again just as quickly; in knowing what awaits you as perpetrator or victim in each of the stories, and being unable to stop it.

The crowning touch is the voice of the legendary Beat author William S. Burroughs, a rare instance of stunt casting that worked out perfectly. Michael Nash, who seemed never to have heard of an edgy cultural icon whose involvement in one of his multimedia projects he didn’t want to trumpet in his advertising, sought out and cast Burroughs for the game without Lees even being aware he was attempting to do so. But Lees was very, very happy when he was informed of it. Burroughs plays the part of your crotchety uncle in the game, and also provides two non-interactive Edgar Allan Poe recitals for you to stumble across: of the poem “Annabel Lee,” which you can hear earlier in this article, and of the story “The Masque of the Red Death.” One anecdote which Lees has shared about the three days he spent directing Burroughs’s performances in the author’s Lawrence, Kansas, home is too delicious not to include here.

He liked starting off the day by toking up. We’re in the [sound] booth and he’s lighting up his marijuana and he says, “Do you want a drag?” And I say, “You know, Inscape’s spending a lot of money to send me out here. I think I have to stay on the ball. You go ahead.”

So, he’d start off by getting a little bit high, and that would loosen him up. Then in the afternoon he liked to drink vodka and Sprite. He would start around 3 PM, and things would get a little mushy, but it also brought some interesting performances out.

I have to admit that on the very last day when we were finishing up, he lit up a joint, and I did share it with Bill.

Within two years of these events, the confluence of cultural forces that could produce such an anecdote would be ancient history. Russell Lees was about halfway through the production of a game based on the Tales from the Crypt comic books and television series when Michael Nash sold Inscape to Graphix Zone, a Voyager-like publisher of multimedia CD-ROMs that was scrambling to reinvent itself as a games publisher in a changing world. The attempt wasn’t successful: the conjoined entity, which was known as Ignite Games, disappeared by the end of 1997. Nash went on to a high-profile career as a music executive, and was instrumental in convincing the hidebound powers that were in that industry to reluctantly embrace streaming rather than attempting to sue it out of existence in the post-Napster era. Russell Lees continued to bounce among the worlds of theater, home video, and games for many years, until finding a stable home at last as a staff writer for Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed franchise in 2011.

As the fate of the company that developed and published it would indicate, The Dark Eye wasn’t an overly big seller in its day. Yet it’s still remembered fondly in some circles today — and deservedly so. It solves one of the basic paradoxes of licensed works by not attempting to replace the stories on which it’s based, but rather to complement them. If you haven’t read them before playing it– or if you haven’t done so since your school days — you might find yourself wanting to when you’re done. And if you have read them recently, the new perspectives on them which the game opens up might just unnerve you all over again. Then again, you might merely be bored by it all. And that’s okay too; not all art is for everyone.

(Sources: in addition to the Edgar Allan Poe collection that belongs in every real or virtual library — the Penguin one is excellent — the book DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text by Mark Parker and Deborah Parker; Computer Gaming World of April 1996 and May 1996; Electronic Entertainment of August 1995; MacAddict of December 1996; Next Generation of August 1997; Wired of March 1995; Los Angeles Times of July 12 1994 and February 28 1997; American Literature of November 1930. Online sources include “What Happened to Multimedia?” by Ralph Lombreglia in Atlantic Unbound and an accompanying interview with Michael Nash, Emily Rose’s podcast interview with Russell Lees, and Lees’s own website.

The Dark Eye isn’t available for sale, but the CD image can be downloaded from The Macintosh Garden; note that you’ll need StuffIt to decompress it. Unfortunately, it’s a Windows 3.1 application, which means it’s somewhat complicated to get running on modern hardware. But you can do it with a bit of time and patience: Egee has written a very good tutorial on getting Windows 3.1 set up in DOSBox, and you can find the vintage software you’ll need on WinWorld. Another option is to run it on a real or emulated classic Macintosh, as the CD-ROM is a hybrid disc for both Windows and Mac computers. See my article on ten standout Voyager discs for some advice on doing this.)