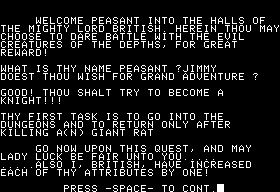

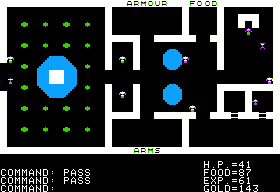

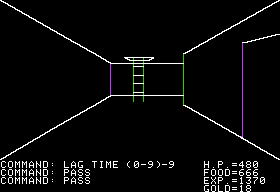

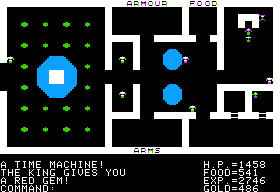

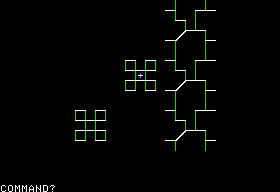

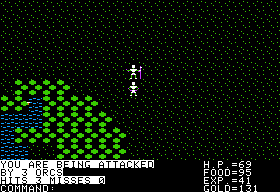

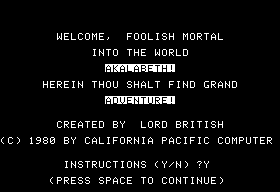

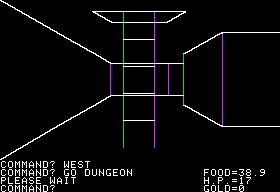

As anyone who’s ever played an Ultima can tell you, our first step upon beginning a new game must be to seek out the castle of the in-game version of Lord British. Unlike in Akalabeth, shown to the left above, castles in Ultima are implemented as little navigable worlds of their own, complete with king, guards, jesters, and even a handy princess awaiting rescue; in the image below I’m standing at the bottom right, just outside her cell.

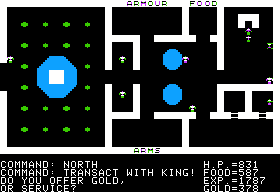

Every castle, like every town, is identical except for its name and the king we find there. Like in Akalabeth these kings provide us with direction for the bulk of the game in the form of quests, a welcome design choice that helps Ultima, again like Akalabeth, avoid the sense of aimless needle-in-a-haystack wandering that plagues so many other early adventure games. In Ultima, we can also opt for “gold” instead of “service” when speaking to a king, meaning we can trade cash for hit points.

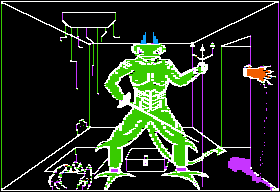

Here I have to take a moment to talk about this game’s, um, unusual approach to character building. Hit points here are a collectable resource awarded by the game or bought from kings, with no relation to anything else about your character. There is, in other words, no maximum total of hit points to which you can be healed and, indeed, no real concept of healing at all. You simply earn hit points questing or buy them from kings, and spend them fighting monsters. And that’s just the beginning of the strangeness. The game provides a running total of experience points, but I haven’t been able to actually determine what they do for you. In a Republican’s fever dream of a socialist dystopia, leveling up is simply a function of hours spent on the job; every 1000 turns earns you another level. (There’s actually no variable at all in the code assigned to your character’s level; the game just divides time by 1000 every time it needs to print your level.) And then there’s the game’s oft-remarked obsession with food: you consume a little bit with every move, and if you ever run out you die — instantly. I kind of like what one Ophidian Dragon said about Akalabeth‘s food system, which worked the same way: “It’s like you have a gigantic bag of potato chips on your back, and are constantly munching on them, and when the bag is empty you instantly die!” Such absurdities are sometimes necessary to make of a piece of ludic narrative a playable game, but the mechanics of this and later Ultimas are often suspect not just from a narrative but also from a game-design perspective. The joy of Ultima is more in exploration and discovery than in strategizing. In other words, Ultima is no Wizardry (and vice versa — and if you don’t know what I’m talking about, well, we’ll be getting to Wizardry soon).

After leaving Lord British, we head for the nearest town — Britain, natch — to stock up on supplies. Like the castles, the towns are now implemented as navigable environments of their own, albeit once again all identical. There’s an unusually off-color element here in this otherwise asexual world: if we drink too much at one time in a pub (in best D&D fashion, a necessary source of hints and tips about goings-on), we get seduced by the local wench, who gives us a “long night” but takes all our money in return. I suppose you get what you pay for. (And apparently our character is a heterosexual man. Good to know.)

More productively, we can pick up some new armor and weapons. Trouble is, we’re not exactly flush with cash. Luckily, there’s the handy “Steal” command. But if we get caught, the whole town goes apeshit and comes after us. So we do what Ultima players have been doing for time immemorial: save our game outside town (the only place saving is allowed), then enter and try our luck. With a bit of patience if not much fidelity to the game’s fiction, we eventually equip ourselves with plate armor and a blaster. “Wait,” I hear you say, “a blaster? Like a Star Wars blaster?” Just hold off; we’ll get to that.

Incidentally: in one of those user-interface choices that make these early games such a delight, we steal by pressing “S.” We’re thus pretty much guaranteed to do lots of accidental stealing when we really want to “sell,” at least until we’ve gotten it pounded into our little heads that the command for selling is actually “Transact.” And don’t even get me started on “Klimb,” or the immortal “Ztatistics” command.

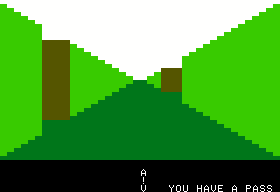

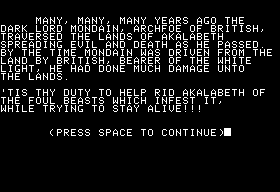

Journeying onward, we spend some time killing monsters outdoors to build up our cash reserves and test out our ill-gotten hardware. Then we visit the Castle of the Lost King and accept our first quest: to kill a gelatinous cube. Doing so requires venturing into a dungeon. And doing that in turn brings on a case of deja vu: the dungeon-delving part of Ultima has been left unchanged from Akalabeth.

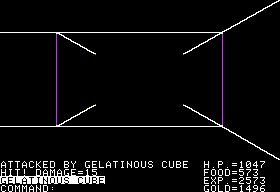

Well, I say unchanged, but it sure feels like it’s gotten even slower. Most of one’s time underground is spent watching the screen lugubriously redraw itself. A few of Mr. Arnold’s assembly-language routines would have been welcome here. In between redraws, we fight a mixed bag of monsters, many of them, like the gelatinous cube we’re after for this first quest, drawn straight from the D&D Monster Manual. (A quick way to guess whether a given monster is drawn from some mythology or fiction or original to D&D: the more ridiculous it is, the greater the chance of the latter.) The gelatinous cube is kind of annoying in that it’s really, really hard to see against the walls of the dungeon itself.

It’s also kind of annoying in that it eats our armor when it hits us successfully. We could carry nine or ten suits of plate mail with us for occasions just like this (no sniggering on how ridiculous that is!), but, thanks to a bug or Garriott’s just never having gotten around to it, it’s actually impossible to equip new armor while in a dungeon. Sigh.

So, by this point the structure of the game begins to become clear. There are eight castles to be visited, arranged, in that symmetric way so common to made-up worlds, two to a continent. Four of the kings — you guessed it, one per continent — send us on quests to kill progressively more dangerous monsters at progressively lower dungeon levels. When we complete each of these quests, each king gives us a gem, and also babbles something or other about a time machine.

The other four send us to seek out above-ground landmarks, but only raise our strength score in return. (The landmarks themselves raise our other statistics.) Of course, all is not as easy as it sounds. Unlike the later games, Ultima shipped with no map of its world, meaning just finding all of the castles and landmarks requires quite a bit of patient, methodical exploration. At least our searching expends the turns needed to gain levels, a good thing considering we need to get to at least level 8 to finish the game.

One thing we can do to speed our development is to rescue princesses. Note the plural; there’s one in every castle, and since each castle is reset as soon as we leave it we’ve got an effectively infinite supply of damsels in distress. Exactly why these presumably benevolent kings are keeping the poor princesses under lock and key is never adequately explained. Indeed, Sosaria is not so much a world as a shadowy projection of the possibility of a world, onto which we can graft our own fictions and justifications. Or not: as we’ll soon see in the context of the princess as well as other things, there are plenty of signs that Garriott doesn’t take it all that seriously himself.

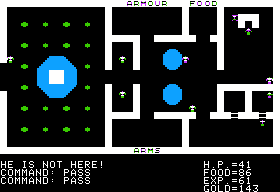

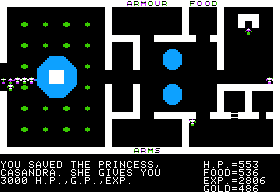

Rescuing a princess first involves killing — yes, killing, in cold blood — the jester who is helpfully yelling, “I’ve got the key!” every few turns. After that the castle guards go predictably apeshit, while we check our “Ztats” to see whether we got the key to Cell #1 or Cell #2. In the former case, we can only run for it — or restore a saved game — and try again. In the latter case, we can effect our rescue. In the screenshot below I’m at the extreme left edge, just making my escape with the princess and most of the castle guards hot on my heels. My reward is 3000 hit points, 3000 gold pieces, and 3000 experience points. Not bad.

Now, there’s so much about this game that is so ridiculous that it’s hardly worth flying into a rage about the moral shadiness of all this. I do want to be sure to point it out, however, because Garriott would later have something of an epiphany after taking a hard look at the many situations like this in his own works and decide to stand up for morality. But that’s a story for another time.

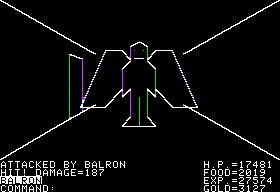

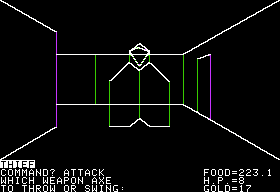

We eventually acquire the fourth and final gem by killing a “balron,” a creature that in Akalabeth was named after the balrog of Gandalf-killing fame. As the game industry grew in size and public exposure, Garriott and other designers slowly found themselves having to be more careful about the niceties of copyright law. He even made some efforts in Ultima to rename some of the obviously D&D-inspired monsters; the carrion crawler, for instance, becomes the “carrion creeper.” Anyway, Garriott’s balron looks more like a kid in an angel costume than Gandalf’s “foe beyond any of you.”

Notice in the screenshot above the ridiculous number of hit points we’ve bought by this point.

With the balron dispatched, we’re about to move past the mushy middle toward the climax. And things are about to get weird. We’ll try to finish up next time, if we can manage to find a plot. I’m pretty sure there’s one around here somewhere.