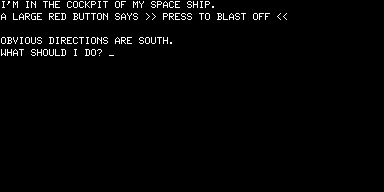

By the time that Adventureland had its first anniversary, adventure games on the TRS-80 were already amongst the platform’s most popular software offerings. And now, thanks to Scott Adams’s portable adventure engine and the fact that virtually all non-Adams adventures were still written in relatively standard BASIC, they had begun to pop up on other microcomputer platforms as well. A new art form was on the scene. As early as its June, 1979, issue, SoftSide published an “Engagement Announcement” between the TRS-80 and “Fantasy”:

The staff of SoftSide is eagerly anticipating the birth of a new art form as a result of this match. We feel that one of the most creative art forms of the future will be the participation novel, in which you assume the role of a character and alter the direction of the story by your own actions, instead of simply reading what the original author conceived and wrote.

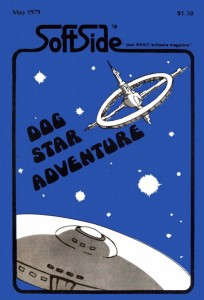

Right now, creative people who’ve been writing elaborate simulation games are working on computer adaptations. The progress they’re making is exciting, with greater things to come! In our December issue, we presented Santa Paravia en Fiumaccio, breaking new ground in simulations on computer. [Written by Reverend George Blank, Paravia was an adaptation / expansion of Hamurabi, a resource management strategy game dating back to 1968 and eventually ported to BASIC by David Ahl, founder of Creative Computing magazine. As the first computer game to explicitly ask the player to play a role in a storyworld of sorts, Hamurabi is of great historical and theoretical significance in its own right.] In May we presented you with Dog Star, bringing us one step closer to the electronic novel. We foresee the time when elaborate simulations of high literary and artistic quality will captivate the leisure hours the way television does today, in much the same manner that television replaced radio drama, and radio drama led to a decline in reading for pleasure.

In March, SoftSide was contacted by the publisher of The Dungeoneer and Judges Guild Journal, two magazines specializing in the simulation game Dungeons and Dragons. In a copy of The Dungeoneer we were surprised to find a list of sixty-one other magazines also specializing in fantasy, war and simulation games. We also discovered that many of these people are starting to use the TRS-80. [I’ll be exploring this linkage between the nascent computer-game industry and the rapidly expanding world of tabletop role-playing games very soon.] Once the creative work they’re doing is suitably married to the computer, the electronic novel will be born! We’re certain the day is not far off, and we intend to be part of it!

Shortly afterward, SoftSide began using the rather awkward term “compunovels” to refer to these new works, the first of many attempts by writers, commentators, and players to get away from the somewhat limiting labels of “adventure games” or (a bit further on) “text adventures” to something reflective of more literary aspirations.

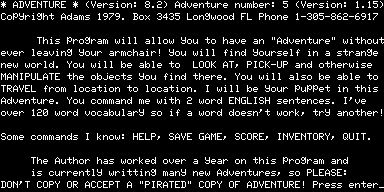

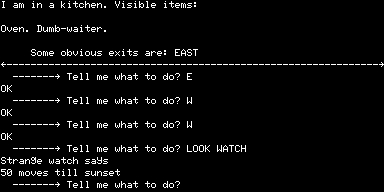

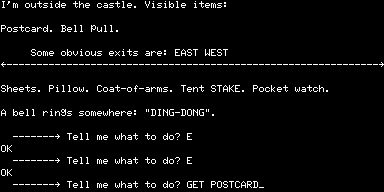

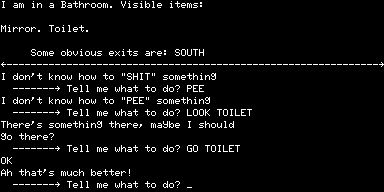

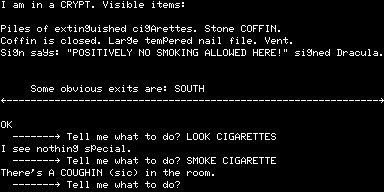

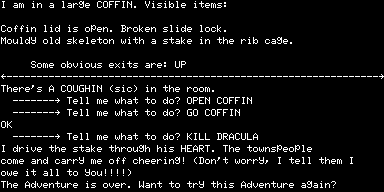

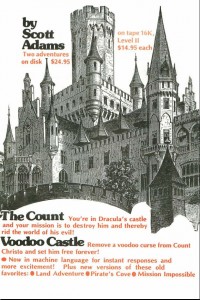

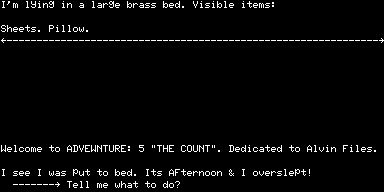

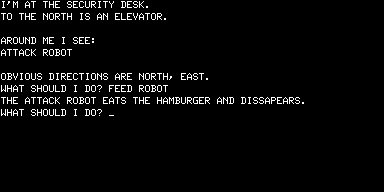

Of course, the idea of the “compunovel” was more aspirational than it was reflective of the reality of 1979, when the Scott Adams games with their childlike diction, “weirdly errant grammar” (in the words of Graham Nelson), and merest stubs of plots were the class of the adventuring field. Indeed, for many contemporaries these claims for literary grandeur must have seemed downright delusional given the reality of the time. It’s to the great credit of the writers at SoftSide that they could see the potential of the new form once freed of the technical constraints of 16 K of memory and cassette-based storage, and of the artistic constraints imposed by programmers attempting to get by as writers.

Still, there was another culture that was largely free of the first if not the second set of constraints: the institutional hacking culture that had birthed adventure games in the first place. By 1979 the big machines hosted quite a variety of them: Zork at MIT; Stuga, the first adventure game created outside of the United States and the first in a language other than English, at Stockholm Computer Central; Acheton at Cambridge University in England; Mystery Mansion at (of all places) the Naval Warfare Engineering Station in Keyport, Washington. Meanwhile others, free of the commercial considerations that were already coming to dominate the microcomputer software market, set about improving and expanding upon the original Crowther and Woods Adventure, creating a dizzying number of variations that have come to be referred to by their maximum possible score. The original game, which offered 350 potential points, is sometimes called Adventure 350, while its successors include Adventure 365, Adventure 550, and many others, finally many years on culminating in the inevitable Adventure 1000. Even Woods himself created an expanded 430-point version before leaving adventure creation behind for good.

The most immediately striking characteristic of all of these games today is their sheer size; they still remain some of the largest text adventures ever constructed in breadth if not depth, boasting hundreds of rooms each. Their scale was a byproduct of the culture that created them. In the hacker ethic, no program was ever considered truly finished; there was always room for more tweaking, more features, just more. Since these games were not commercial endeavors, there was no necessity to declare them done and ship them out the door at any given point. They therefore often remained in a sort of playable development stage for literally years, growing in fits and starts as the interest levels of various contributors waxed and waned. (Another thing which distinguished these games from their microcomputer counterparts, and indeed from most IF of today, is that they tended to be team efforts.) Zork, for instance, first appeared on MIT’s computer system in May of 1977, hot on the heels of the Adventure phenomenon, but was not finished until February of 1979. Even at that point, the game was not really done in any thematic or design sense. Its creators had simply managed to fill up even the cavernous one megabyte of memory on their DEC machine, and thus were physically unable to continue to build yet more new rooms.

If you’re thinking that such a development model might ultimately be as limiting to narrative possibilities as were the absurd hardware limitations of early home computers, well, you’re pretty much right. The team that created Zork, for instance, contained some genuinely talented writers, perhaps more so than anywhere else in the adventuring world of 1979. Yet their best efforts were continually undone by the “too many cooks in the kitchen” syndrome, with descriptions of real imagination and elegance juxtaposed with others of a Scott Adams-like terseness. And the design itself is similarly sprawling and unfocused, with great ideas layered upon less great ones in seemingly random fashion. Zork and other, possibly even larger games like Acheton are vast and chaotic almost to the point of incomprehensibility. In this light the technical constraints of microcomputers, which forced authors to create games that were thought-through, structured designs rather than random sprawls, don’t look quite so bad. Or, to put it another way: bigger is not always better. It’s telling to note that none of these games had a narrative arc anywhere near as tight and coherent as that of The Count.

Still, TRS-80 owners working their way through the constrained environments of Adventureland, Dog Star Adventure, and The Count might be forgiven for casting some jealous glances in the direction of all those rooms, all those objects, all that space for text. It was therefore kind of a big deal when the daddy of all those institutional extravaganzas, Adventure itself, first came home. If Adventure could be made to run on a TRS-80, it seemed reasonable to think that other larger, more ambitious games should soon be possible on microcomputers as well — which was of course exactly what ended up happening. Indeed, within a few years adventure-game development on the big machines would pretty much dry up entirely.

The name of the company that first brought Adventure home via the TRS-80 might just surprise you. More on that, and them, next time.