Time Zone met a fairly cool reception upon its release. It wasn’t panned in the magazines; bad reviews were all but nonexistent in this era. Still, it received surprisingly little coverage for such a major release from such a major publisher. When it was discussed, the main preoccupation was its immense size, with little attention given to its other qualities. Most likely those assigned to write about it were as intimidated by it as everyone else, and didn’t know quite where else to begin.

Feedback from the everyday gaming public in the only form that ultimately matters to a publisher, sales, was also very disappointing. As they had for the other Hi-Res Adventures, On-Line had announced plans to port the game to the Atari 400 and 800 — where, thanks to the small disk capacity of those machines, it was projected to occupy an astounding 20 disk sides. In the wake of very poor sales, however, they quietly shelved those plans, judging it not worth the effort. Within a few months all active promotion had ceased, as On-Line wrote the game off as a failed, not-to-be-repeated experiment and moved on. Luckily they still had plenty of more successful software, enough so that the Time Zone project, while it certainly didn’t help the bottom line, didn’t by itself endanger the house that Ken and Roberta had built.

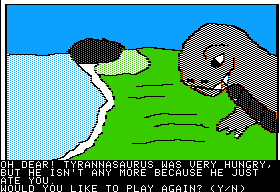

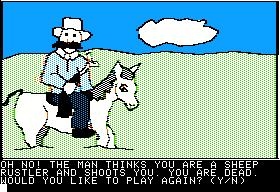

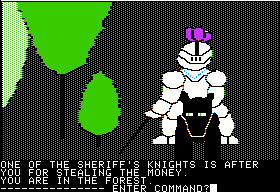

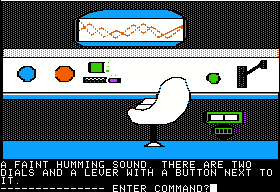

It’s tempting to see in Time Zone‘s failure the adventuring public standing up for their rights at last, rejecting the absurdities of the genre to the strains of “We’re Not Gonna Take It” (hopefully the Who’s version rather than Twisted Sister’s). Alas, this probably wasn’t the case. Cruelty and unfairness were still largely what was expected of an adventure game at this stage. Of the games I’ve looked at so far for this blog, only (bizarrely enough) Softporn is not at least a little bit sadistic, and that hadn’t prevented many of them from becoming hits. Time Zone‘s sins were not so much unique as compounded by its size, affirmatively answering the question of whether a game could be simply too big.

The other question Time Zone answered was whether an adventure game could cost too much, and therein lies the more obvious reason for its failure. Prices had escalated rapidly since the days of 1978, when individual programmers had sold games in Ziploc baggies for $5 or $10. Publishers watched in delight as they raised their prices — to $20, $35, finally to $50 with the arrival of Wizardry — and people just kept on buying, even as the United States and the world plunged deeper into the worst recession prior to the recent one. Looked at from today’s perspective, the games business circa 1982 looks like the proverbial license to print money, as publishers could sell games created in a few months by one or two programmers for prices that were, when considered with inflation, equal to or greater than those of modern AAA titles developed by teams of hundreds. Yet there was a limit, and Wizardry and Time Zone by their respective success and failure pretty definitively found it. From then on publishers would not dare to venture much beyond $50 for even their most lavish productions. As the public’s expectations went up, resulting in games that needed bigger development teams and ever more time to make, profit margins correspondingly shrank. No wonder so many game-makers from those halcyon days can’t help but look back on the early 1980s with a certain wistfulness.

There were of course some people who bought Time Zone, and even some who claimed to enjoy it. It managed to place 20th in Softalk magazine’s readers’ poll for the best software of 1982, beating out the likes of Infocom’s Deadline. And Electronic Games magazine gave it a year-end “Certificate of Merit.”

The most prominent fan of all was Roe R. Adams III, the prolific adventure-game reviewer and columnist for several magazines who according to legend became the first in the world to solve the game, just one week after its release, and according to Steven Levy’s Hackers then “declared Roberta’s creation one of the greatest gaming feats in history.” Adams was active on a telecommunications service known as The Source, an important early online community that was the first of its kind barring only PLATO, and as such is probably worthy of a post or three in its own right. After watching his other, less adept adventuring friends flounder in the game, he convinced the powers that were on The Source to set up an area called the Vault of Ages, dedicated to plumbing the mysteries of Time Zone collaboratively. Users were greeted with the following upon going there:

Welcome to the Vault of Ages. Here we are coordinating the greatest group effort in adventure solving — the complete mapping of On-Line’s Time Zone.

I am the curator of the vault. You are the 85th intrepid time traveler to seek the knowledge of the vault. Herein we are gathering, verifying, and correlating information about each time zone. Feel free to visit here anytime, but remember that for the vault to fill, we need your contributions of information. Anytime you have new information about mapping, puzzle solutions, traps overcome, items found, s-mail this info to me. After verification, your contributed jigsaw puzzle piece will be added to the vault file, and your name will be entered upon the rolls as a master solver. Now step this way and I will introduce you to the Master Catalog.

Eventually with more than 1800 members, the Vault of Ages is a fascinating example of early crowd-sourcing, an ancestor of everything from Wikipedia to a thousand Lost message boards, and as such of perhaps more ultimate significance than Time Zone itself.

Within On-Line, Time Zone was notable in retrospect for being the first project of Jeff Stephenson. The great unsung hero of On-Line’s (soon to be Sierra’s) glory years, Stephenson would largely take over from Ken Williams as the company’s hacker-in-chief as the latter found business concerns monopolizing his time. Stephenson became the technical architect behind the next two generations of Sierra adventure games, designing the AGI and SCI engines and development tools that allowed Sierra’s games, like Infocom’s, to run on any platform for which the company wrote an interpreter. We’ll be getting much more familiar with Stephenson and his work in the years to come.

Still, most within On-Line were happy to forget about Time Zone as quickly as possible. That’s not all that surprising, given the chaotic development process, the unsatisfying final result, and the commercial failure of the project. Yet it went beyond even that. There was something ill-starred about Time Zone that seemed to affect many involved with it. Most of the youngsters who worked on the game left for university or other greener pastures upon its completion, happy not to have anything more to do with the games industry. Terry Pierce, the 18-year-old artist who had drawn all of those 1400 pictures virtually singlehandedly, burned out more dramatically. He was the best friend of Ken’s little brother John, who was only slightly older but already filling numerous high-profile roles at On-Line, including putting together the packaging for Time Zone. John describes a “kind of psychotic episode,” in which Terry was found “walking down the snowy highway at night in below freezing weather with no shoes or shirt on.” He also was gone shortly after that incident, severing all contact with his erstwhile best friend and everyone else at On-Line for over 20 years.

But the saddest tale of all was that of Bob Davis. Davis, you’ll remember, was the personable fellow who had gone from clerking at a liquor store to designing his own game to heading the Time Zone project in six months. He had a history of alcoholism and drug abuse, but had managed to get himself basically clean and sober by the time he started working for On-Line. But around the time that Time Zone was wrapping up, Davis, making more money than he ever had in his life, started to indulge in a big way again. He quit his job shortly after, deciding he could write games on his own and sell them to publishers. Davis was a bright guy when sober, but he hadn’t a prayer of authoring a game from scratch when bereft of tools like Ken’s ADL adventure-scripting language. He fumbled with learning assembly language for the Atari VCS, one of the most notoriously difficult programming platforms ever devised. But mostly he shot up drugs.

Soon the royalty checks started to get smaller as his game Ulysses and the Golden Fleece went from new hit to catalog status, and soon after the money was gone along with his wife. Davis began calling On-Line’s offices on an almost daily basis, asking for a job he obviously was no longer capable of doing — or, even better, just a straight handout. Knowing where the money would go if he just gave it to him, one kind-hearted old colleague offered to pay his mortgage directly; Davis angrily slammed down the phone in response. He started trying to pass bad checks all over town, becoming a pariah in this small community where everybody knew everybody. In a story that rings familiar to all too many of us, he “flamed out in a way that burned every bridge along the way,” in John Williams’s words, and by the end of the year was in jail in Fresno. I don’t know what happened to him after that, although I can say that he never rejoined the games industry to build on his unlikely early success. John believes he called On-Line just once after his release from jail, to an understandably “chilly reception.” But Bob Davis, first through all those increasingly desperate phone calls and then through the bad memories of his fall from grace, haunted On-Line for years afterward, casting a pall over everyone’s memories of Time Zone itself.

And that sad note is where we’ll have to leave it with Time Zone. As we’ll soon have several occasions to learn again, individuals and companies could fall as fast as they rose in the early PC industry.