The Prisoner was a big sales success, at least by the standards of a small software house like Edu-Ware. Enough people were eager to believe in a vision of games as Art to embrace it despite its almost aggressively off-putting personality — or, perhaps, they were just desperate enough for new adventures that they were ready to put up with artistic aspirations as long they also had puzzles to solve. Regardless, the game played a crucial role in the company’s idealistic core mission, to bring quality educational software to this new generation of personal computers. The steady flow of profits from The Prisoner gave Edu-Ware, supported by Apple’s own efforts to define the Apple II as “the education computer,” time and resources to build a customer base of schools and engaged parents for titles like their Compu-Math and Algebra series.

Yet times were changing fast in software, and particularly in entertainment software. Even by just eighteen months after its release The Prisoner — with its sluggish all-BASIC implementation, its blocky, monochrome text or low-resolution graphics displays, and its photocopy/Ziploc-bag-based packaging — was beginning to look sadly amateurish in comparison with the latest extravaganzas from the likes of On-Line and Brøderbund. Edu-Ware therefore decided to remake their cash cow in a more polished, slicker, faster edition, with color and more and better graphics. Confusingly, they decided to call the new game The Prisoner 2, even though it was very much a remake rather than a sequel. Marketing never was Edu-Ware’s strong suit.

The new project reflected changing models of development, not only within a growing Edu-Ware but also within a growing software industry. The original had been cranked out by David Mullich in a furious six weeks of hacking. There was no separate design process; he simply designed as he coded, adding in whatever seemed cool and appropriate as it struck his fancy. By the time of The Prisoner 2, however, Mullich had acquired the title of “development manager” at Edu-Ware, with a staff of several programmers working under him on the company’s various projects. Having gotten more adept at 6502 assembly language since the time of the first game, he himself programmed some speed-critical routines for graphics that were also used in other Edu-Ware titles, as well as a text parser. He also drew the game’s graphics on paper. But to translate those drawings onto the computer, and to code everything else, he employed one Mike St. Jean, who worked, once again in BASIC, from a detailed design document provided by Mullich. Mullich was, in other words, transitioning from the jack-of-all-trades hacker typical of the very early PC era to this new creature known as a “game designer.” Those aforementioned assembly-language routines would be, in Mullich’s own words, “among the last programs I actually coded myself” in a career in software that continues to this day.

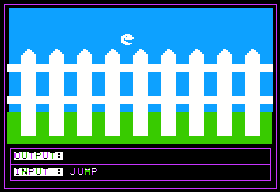

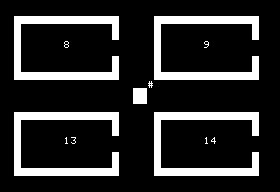

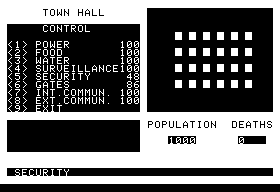

The results of his efforts are, as is all too typical of remakes, mixed. While it may have had at least as much to do with lack of time, expertise, and resources as artistic intent, the original’s stark, Constructivist appearance did much to strengthen the atmosphere of oppression, coercion, and collectivist subjugation. The Prisoner 2, by contrast, looks at first glance like just another “hi-res adventure” of the sort that were flooding the market by 1982 in response to On-Line Systems’s success, and the maze section that opens the game bears a pronounced resemblance to, of all things, the Wizardry series.

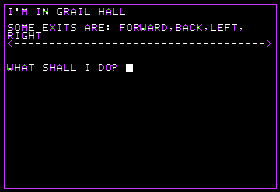

Likewise, the variety of different interfaces found in the original game, which the player had to puzzle out on her own to succeed, is here replaced in almost all places by a two-word parser that is unusually balky even by the standards of the time. It’s tempting to read some of its obstinacy as another instance of the old Prisoner tactic of resisting consistent interface standards to keep the player always ill at ease. How else to read the fact that the parser sometimes demands that you navigate with “forward,” “back,” “right,” and “left,” and other times with traditional compass directions? Still, it just somehow doesn’t quite work as well as the first game’s interface smorgasbord.

The new, more professional presentation must inevitably also become more technically opaque, removing some of the possibility for winning through, um, other means like code-diving. This might be a good thing in any other game, but, as Steve Pederson wrote in response to my article on the original Prisoner, in this case “nothing could be more in the spirit of the game [than cheating].”

A comparison of the manuals also gives me conflicted feelings. The original shipped with only the most essential information on the game and some slightly pedantic “educational notes” penned by Edu-Ware founder Sherwin Steffin. For the sequel, this document was replaced with a slicker production which elaborates a mythology of sorts for The Island and even for the original Prisoner television series. The Island, we are told, was created in the 1960s in response to the agitations of the counterculture.

It was in this climate that The Island was created. Its purpose then was to silence dissenters and to perpetuate authoritarian rule. Leaders of various social movements and government operatives who learned too much of their employer’s plans both unwillingly found themselves a new home on The Island — until such time as they were absorbed back into the system or died. But, from the perspective of the rest of the world, they had vanished without a trace, presumably the victims of foreign or illegal organizations.

Towards the end of the decade came the first exposé of The Island. It was presented in the form of a television adventure series so that its producers could circumvent the problems of censorship. Its focus was as a psychological study and a political statement concerning the problem of keeping one’s individuality and personal freedom in a technological society. While it did gain a cult audience, its messages did not receive the recognition that they deserved.

So, the influence of The Island spread unchecked in the seventies. The “me” generation proved to be a perfect target not only for The Island’s sinister activities, but also for one of the most powerful weapons of mass enslavement ever created: the computer. Ever increasing meddling by computer networks, data bases, and information peddlers in our daily lives forced us close to the verge of becoming mere numbers within the memory banks of hundreds of machines across the country. More and more information about us became accessible to anyone who had a link into the proper data base. With the flip of a switch, instantly our reputations could be tarnished and our influence destroyed. Lives became statistics, and statistics could be altered.

In short, the computer was turning society into a vast collective prison.

In the debate that raged through the 1970s and 1980s (and to some extent still today) on whether the computer was a tool of liberation and creative possibility or a tool for dehumanization and subjugation, this narrative comes down on the latter side. Yet The Prisoner 2 is of course using a computer to make just the sort of creative, humanistic statement it says the computer will stamp out. As always where The Prisoner is involved, the contradictions bite deep.

Mullich has here totally abandoned the notion from the original game of merely being “inspired by” the television show. He is now explicitly playing in the same storyworld as the show — and doing it without any sort of licensing deal with The Prisoner‘s corporate parent ITC Entertainment, who were either unusually benevolent or very unobservant. Ironically, Mullich later in his career would join Disney, where he would spend some of his time stamping out just this sort of intellectual-property infringement.

Eternal debates over intellectual property aside, I’m still not sure how I feel about the sequel’s elaborate backstory. Part of me wants to say that Mullich and company say far, far too much here, that rooting The Island in such a specific historical and cultural context costs them much of the ominously enigmatic feel of both the original game and television series. On the other hand, this more detailed fictional context does enable the most notable new aspect of the sequel: a sharply satirical critique of the videogame craze that was just reaching its first-generational peak when The Prisoner 2 reached stores in mid-1982.

A more disturbing turn of events took place in the eighties, however. Instead of the public becoming cautious of computerization, they took the devices into their very homes. For hours at a time, people would sit blank-faced in front of television sets playing uninspired clones of Asteroids, Space Invaders, and Pac-Man. An entire civilization was willing to waste their precious lives playing mindless games, relentlessly pursuing nursery-school melodies, high scores, and pointless goals.

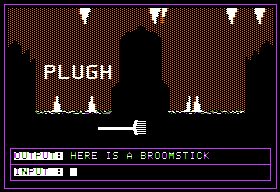

In that spirit, the Rovers, the balloon-like guards who prevented escape from The Island in both the television series and the first game, are replaced in the sequel with… Pac-Man.

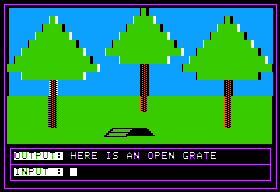

As good adventure gamers, we might be tempted to agree with Mullich’s criticism of these mindless arcade games, to assume that our more cerebral games are exempt from his criticisms. But then we come to a building he added just for the sequel: the Grail House. Inside is something that was already becoming a symbol of adventure games at their most banal by this time: an extended maze. The maze includes rooms which specifically reference Adventure, Mystery House, The Wizard and the Princess, and the Scott Adams games.

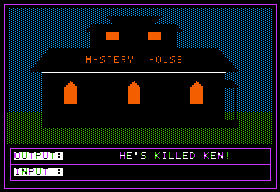

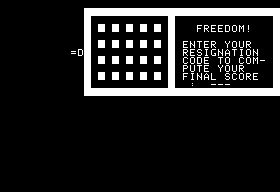

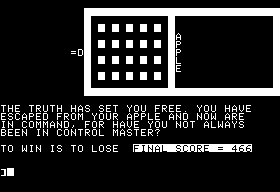

Whether these portrayals are fleshed-out enough to rise to the level of satire is perhaps debatable, but they don’t exactly feel like loving tributes either. The Mystery House room, which flags you as a murderer (presumably of Ken Williams himself) until you find “absolution” in the church, has a particularly abrasive edge to it. Indeed, and especially given the truly awful parser, one could almost read the entirety of The Prisoner 2 as a satire on the absurdities of contemporary adventure gaming. The ultimate goal of the game is after all to free yourself by “escaping” from pointless submission to this world inside your computer, as Edu-Ware’s Steve Pederson is doing in the striking box art.

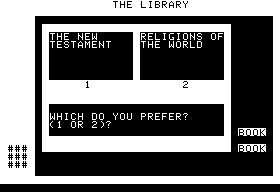

Leaving aside both other adventure games and The Prisoner 2‘s more colorful but less effective appearance (prompted, ironically, by commercial considerations that required keeping up with those very same other adventure games), much of the subversive, anti-authoritarian message of the original game does remain in the sequel. In some places it is even strengthened. The Library in the original, for instance, contained a hopelessly inscrutable free-association scenario whose issue could be a vital clue or a book getting burned. The sequel tries to force you to actively burn books.

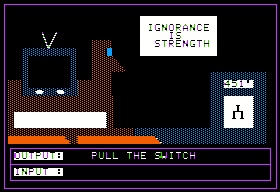

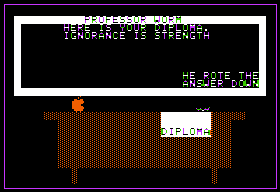

B.F. Skinner’s theories of education come in for even sharper criticism here than in the first game. Succeeding at a series of rote memory exercises leads to a diploma and a wicked pun. (And note the teacher’s apple shaped, once again, like Pac-Man…)

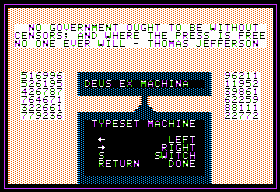

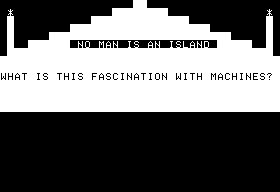

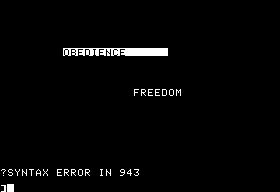

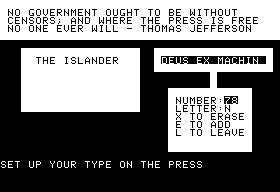

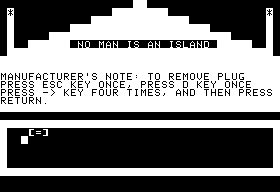

Sometimes the manipulations of truth and perceptions reach new heights of inspiration, such as in this genius re-purposing of a quote from Thomas Jefferson.

We’re tempted to want to add a “be” — or, better yet, a “be free” — to the end. For the record, however, here’s the full quote:

No government ought to be without censors, and where the press is free, no one ever will. If virtuous, it need not fear the fair operation of attack and defence. Nature has given to man no other means of sifting out the truth whether in religion, law or politics. I think it as honorable to the government neither to know nor notice its sycophants or censors, as it would be undignified and criminal to pamper the former and persecute the latter.

Jefferson is here using the word “censor” in an archaic way, as a term for a person who closely monitors and criticizes the actions of another, generally one in a position of power. (Some remnant of this usage persists in the adjective “censorious,” as in condemning an unnecessarily critical critic’s “censorious behavior.”) Thus, far from arguing for censorship in the modern sense, he is arguing for the very governmental openness and transparency that is anathema to the powers that be on The Island.

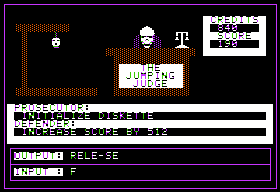

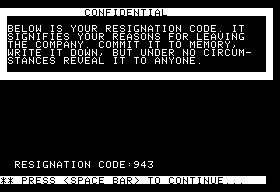

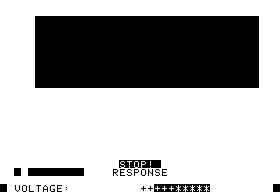

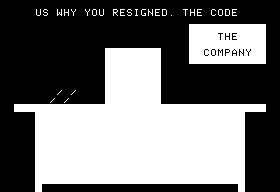

The Prisoner 2 continues to emphasize that it itself is your enemy. In addition to the established dirty tricks from its predecessor (that bogus error message that tries to trick you into entering your resignation code appears again), it has some new ways to be belligerent. At one point it even threatens to re-format the game disk.

No, it doesn’t go quite that far. If you lose this game of judicial hangman, the game tries to fake you out by grinding the disk just like it would during a format, but ultimately declines to actually do the deed.

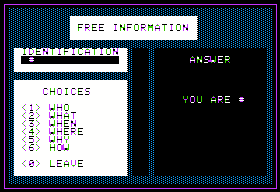

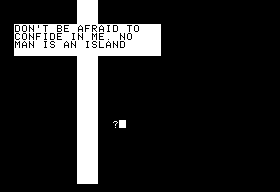

Another amusing fake-out is the computerized “Free Information” booth.

Asking “why” in this section makes the computer go berserk, screen flashing gibberish and disk drives wildly blinking and grinding. In addition to several episodes of Star Trek, this sequence also evokes the climax to one of the classic episodes of The Prisoner television show, “The General.” It’s also, of course, the all-important question that B.F. Skinner’s theories of education don’t prepare students to answer.

So, yes, The Prisoner 2 does manage to get its lumps in. If it doesn’t feel quite as laser-focused in its presentation and rhetoric or, well, quite as necessary as its predecessor, it’s certainly not an embarrassment. Yet, and ironically given its more polished presentation, it was not the same sort of commercial success. Steve Pederson estimates that it only sold in the range of 3000 to 5000 units in total, pretty underwhelming figures in comparison to games I’ve covered recently like Choplifter (9000 copies in its first month) or Deadline (25,000 copies in its first eight months). This was in spite of being ported to the Atari 400 and 800 and the IBM PC in addition to the Apple II. The entertainment-software market was growing rapidly, but Edu-Ware’s share in it was not.

To begin to understand why that should be, we might look to tensions and contradictions within Edu-Ware itself. Edu-Ware’s president and founder, Sherwin Steffin, had no great investment in games. As his company’s name would imply, his passion, a product of his long and ongoing career in education, was educational software. The company’s two other important players, Mullich and Steve Pederson, were each a generation younger than Steffin, and much more interested in computers and games for their own sakes. Steffin was happy to allow them to indulge their interest as long as everyone also strove to develop the high-quality educational software that he had founded the company to create — and luckily so, as the first Prisoner turned out to be a gold mine that helped get his own projects off the ground. Yet by 1982 those projects were able to fly on their own, with programs like Algebra 1 selling in the tens of thousands. As Pederson has said, “As time went on, it became harder and harder to justify game development.” Edu-Ware didn’t need games anymore, and with a hungry market for their educational software and a president rather disinterested in the field, the company had begun the gradual process of abandoning the games market even as The Prisoner 2 was being released. As a retread (however well done) of an older game and with an unengaged corporate parent, The Prisoner 2‘s lackluster sales performance is not so surprising. Edu-Ware’s last big game release, the final, less than compelling installment of its Empire trilogy of science-fiction RPGs, appeared early the following year. And that was pretty much that for the Interactive Fantasies line to which The Prisoner games had belonged.

In July of 1983, Edu-Ware was purchased by a much larger company that had heretofore focused on software for big institutional machines, Management Sciences America. There are a couple of ways to see this development. On the one hand, plucky little Edu-Ware looked to already be facing an uncertain future in the educational market it had pioneered, as new companies like Spinnaker with established corporate parents entered with slick new products for the growing numbers of Apple II-devoted educators and parents. Perhaps finding a deep-pocketed parent of its own was the only way for Edu-Ware to have a hope of survival in this new, more crowded world. On the other hand, Sherwin Steffin told me recently via email that “marketing was an area in which I had neither skill nor interest,” and that this purchase was exactly the “exit strategy that I had planned from the beginning.”

What happened next, though, Steffin had most certainly not planned. He, Mullich, and Pederson were allowed to work without disruption for only a short time before relations collapsed in a pile of accusations, ultimatums, and, eventually, lawsuits. The Edu-Ware brand was largely merged into MSA’s Peachtree line of productivity software in 1984, and the last traces of the old company were obliterated by early 1985. By this time Steffin, Mullich, and Pederson were all long gone. It was an inglorious, anticlimactic end for a pioneering publisher, but not, alas, an atypical one.

As usual, I’ve prepared a copy of The Prisoner 2 for those of you who’d like to try it for yourselves. This time that’s especially important. Like its predecessor, The Prisoner 2 writes to the game disk during play, meaning that most of the copies archived on the Internet contain someone else’s half-finished game. I’ve prepared a zip with a clean copy of the Apple II disk, along with the manual (courtesy of the amazing Museum of Computer Adventure Game History). You might also want to have a look at a fascinating document at the Gallery of Undiscovered Entities: David Mullich’s original design document for the game.

Be seeing ewe!