Suppose that in some alternate universe you are William Shakespeare. Strolling about London one day in the late sixteenth century, mulling over plans for your next novel, you come upon some workmen erecting a large wooden structure of peculiar shape. The design of the building strikes you as inappropriate for either a dwelling or a place of business.

A few questions gain you some information about a recent invention (this is an alternate universe, remember) called the “play.” Live people, sometimes costumed and in makeup, are getting up on a flat surface called a “stage” and acting out stories!

The clever people who have designed and built the first stages, as well as the inventors of acting, are right in there writing and directing the best plays they can come up with. (At least the best they can come up with in their spare time — each of these people necessarily has one or two active careers already going.)

In one of the earliest successful plays, dummies representing invading aliens (Frenchmen, perhaps, or Spaniards, from across the Channel) were lowered on ropes from concealed positions above the stage, while the actor (this play needed only one) ran back and forth, following shouted directions from the audience, trying to shoot all the dummies before they touched the floor. The audience liked this play a lot and cheered it enthusiastically.

In a somewhat more recent show, also very popular, the lead actor climbs about on a crazy scaffolding of planks and ladders, trying to accomplish some rather simple-minded tasks, while others costumed as fantastic creatures try to knock him off by throwing barrels. It’s good slapstick fun, and the audiences love it.

“Wait a minute,” you say to these eager people who have been proudly explaining how plays work. “Wait a minute. That all sounds amusing, yes. But l really think you’re on to something bigger. Let me go home and think about this for a while… How many people can you get onstage at once? How many lines can an actor memorize? Can you have it dark on one half of the stage and light on the other half?”

They look at each other. “We’re not really sure,” one replies at last. “Our stages are still pretty primitive. Our actors are all new at the job. Everybody is. Next year we’ll be able to do more. But what should we try to do?”

You don’t have any instant answers for them. A lot of vague ideas suddenly churning. Possibilities. …

“I hope you will go home and think about it, Will,” says one of the stage managers. “You’re good with words. Maybe we could have the man on the ladder say something more than ‘Ouch!’ and ‘Wow!'”

“Yes, something more,” you agree thoughtfully, turning away. The other stage people call good wishes after you. But you scarcely hear them. Your mind is involved with new ideas.

To work with — depend on — carpenters, actors, experts in stage machinery and lighting? Whatever story emerged would no longer be purely your own. But already you can see that the stage those others have created can capture the imagination and enthrall an audience, even with no more than a few clowns and ladders.

You head for home, for a place where you can sit down and think, and write. Your thoughts are on a story that you had planned to make into a book. The one to be called Hamlet…

The words above were written by science-fiction author and would-be gaming entrepreneur Fred Saberhagen in a feature article about the possibilities for interactive fiction (“Call Yourself Ishmael: Micros Get the Literary Itch”) in the September/October 1983 issue of Softline — the same article in fact that contained the first published discussion of Floyd’s death in Planetfall and what it portended. Saberhagen, whose own flirtations with interactivity would be considerable but commercially frustrating, was at the vanguard of an emerging conventional wisdom about the intersection of computers, games, and books. He and his fellow pundits that started to emerge during 1983 weren’t the first to begin to think along these lines. The editors of SoftSide magazine had first started writing about the literary potential of “compunovels” back in 1979, truly a leap of faith in light of the strangled prose and plots of the Scott Adams games and the other 16 K adventures that were pretty much the only ones available to PC owners at the time. But it took the efforts of not only Saberhagen but also, and probably more significantly, respectable folks writing for respectable mainstream publications like The New York Times Book Review, Time, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe Magazine, and Scientific American to make of it a full-fledged meme. The boldest pundits declared that we were on the cusp of nothing less than a whole new form of literature that could be as rich, meaningful, and aesthetically brilliant as anything put down by Shakespeare or Melville. Suddenly what had once been dismissed as mere “adventure games” were worth taking seriously.

All of the articles just mentioned focused primarily or entirely on Infocom, the only company in the field whose games could realistically stand up to any scrutiny at all as literary works. Seeing this, and seeing Infocom growing less and less afraid to lay claim to the mantle of literary artists under such persistent stroking, lots of other companies started asking how they could steal some of Infocom’s cultural thunder and get a piece of what the pundits said would be the literature of the future. The players who now started entering the field were a surprisingly motley lot. There were the expected startups as well as old dogs in the software game looking to learn some new tricks. Epyx, Brøderbund, and Electronic Arts amongst others all discovered a latent passion for text, as did of all people console developer Imagic, whose action games for first-generation consoles like the Atari VCS had been enormously successful but who were now floundering like everything else in that industry in the wake of the Great Videogame Crash. But technologists were not the only opportunists looking to jump on the bandwagon Infocom was driving. The huge publishing houses of Simon and Schuster, Addison-Wesley, and Random House also started software arms, as did smaller publishers like science-fiction paperback specialist Baen Books. On the other end of the distributional pipeline, the two biggest American bookstore chains, Waldenbooks and B. Dalton, both set aside areas in their stores for entertainment software, as did the ubiquitous W.H. Smith in Britain. To complete the strange mixture and hedge the bets of their own software arm, Addison-Wesley signed a deal with Infocom in early 1984 to distribute their games to the bookselling trade, an important contract that got Infocom into thousands of bookstores populated with just the sort of literate customers they were trying to reach.

All of this forthright investment in the idea of interactive fiction as a serious literary force by such pillars of mainstream American business feels a bit unbelievable today. Nor is it without a certain note of tragic resonance as the great What Might Have Been for people like me who still unabashedly love the idea. We see here the culture and, at least as importantly, the culture’s business interests trying to work out just what computer games were, what they could be, and perhaps what they should be. It’s a fascinating process to watch, if also — again, for people with my sympathies — one with kind of a heartbreaking ending. Were computer games actually games in the way that, say, Monopoly was? Or were they more like books? Or movies? Or were they — and this was the most messy and complicated and also the most likely answer of all — like any or all or none of the above, depending on the particular title in question and its genre and target audience? The answer to these questions was essential to answer another, more practical one: how, where, and to whom should computer games be sold? The folks we’re concerned with today are those who decided to bet on computer games, or at least a segment of them, as the next iteration in the long history of the book. Even on the business side of the development equation their efforts mix the expected desire to shift a lot of units and make a lot of money with a genuine idealism about the artistic potential of the form in which they were working. It was, as should be more than clear by now, an odd time in media.

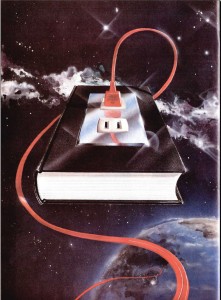

If computer games were or could be literature, and if they wanted to be taken seriously as such, said many people, the smartest thing to do was to get people who already knew how to write literature — or at least readable popular fiction — involved in their creation. Or, failing that, the next best thing must be to play in the rich fictional worlds they had created. Lots of people in lots of companies followed this chain of reasoning simultaneously. Thus began the era of what the British press pithily came to call “bookware,” the splicing of the new frontier of computer games with the old of books and their authors, who were sometimes (but not all that often) actively involved, sometimes disinterested but happy to be getting another royalty check, and sometimes dead and thus blissfully unaware of the whole exercise. A trend that had been presaged in 1982 by The Hobbit reached manic full flower in 1984.

The list of bookware that flooded the market in both the United States and Britain between 1984 and 1986 is long, and includes some of the biggest names in genre fiction of the era as well as some surprisingly high-brow figures. An incomplete list might include: The Robots of Dawn (Isaac Asimov); The Mist (Stephen King); Amnesia (Thomas M. Disch); Mindwheel (future American poet laureate Robert Pinsky); High Stakes and Twice Shy (Dick Francis); Wings Out of Shadow (Fred Saberhagen); The Fourth Protocol (Frederick Forsyth); The Dragonriders of Pern (Anne McCaffrey); The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World (Harry Harrison); The Pen and the Dark (Colin Kapp); The Saga of Erik the Viking (Terry Jones); The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Sue Townsend); The Width of the World (Ian Watson); The Colour of Magic (Terry Pratchett); and Infocom’s own The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Douglas Adams). Those whose tastes ran more to the classics could choose from Pride and Prejudice (Jane Austen); The Time Machine (H.G. Wells); Sherlock (Arthur Conan Doyle); Macbeth (William Shakespeare); The Snow Queen (Hans Christian Andersen); Dante’s Inferno; and Dracula (Bram Stoker). The list of games for which contracts were signed but which went unreleased due to the bookware bubble’s bursting includes Glory Road (Robert Heinlein); another Inferno (this one by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle); Animal Lover (Stephen R. Donaldson); 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Jules Verne); Special Deliverance (Clifford D. Simak); Soldier, Ask Not (Gordon R. Dickson); and The World Thinker (Jack Vance). The publishers involved with all these efforts largely abandoned the old labels of “adventure game” and “text adventure” in favor of ones that reflected their literary aspirations. Some shamelessly appropriated “interactive fiction” from Infocom (who had themselves, of course, shamelessly appropriated it from Robert Lafore). Others made “interactive novels” or “computer novels.” Bantam Software came up with a particularly catchy label: “living literature.” Mosaic in Britain just bowed to the inevitable and stuck “bookware” on their boxes.

But it was none of the companies or games already mentioned who made the biggest bet on bookware. That was in fact a rapidly growing publisher located ten minutes from Infocom in Cambridge which had heretofore specialized in educational software: Spinnaker. Spinnaker debuted not one but two new imprints for bookware in 1984: Trillium (later Telarium, for reasons we’ll get to shortly), for book adaptations aimed at adults and teenagers; and Windham Classics, aimed at a somewhat younger set. They released no fewer than seven games between the two lines in 1984 alone (two more than Infocom’s total output for the year), followed by another five in 1985 and a final straggler in 1986, the twilight of the brief bookware era.

The story of Trillium and Windham Classics begins with a remarkable young publishing mogul named Byron Preiss. Born in 1953 in New York City, Preiss was one of those characters like Steve Jobs who could seemingly talk anybody into anything, one who as a callow youth not yet out of his teens was already able to convince older and supposedly wiser businesspeople to back his many and varied schemes. Throughout his career, Preiss mixed business with an idealism that seems to have been anything but affected. He first made a mark at seventeen, when he wrote and distributed The Block, an anti-drug comic book written for a near-illiterate reading level and aimed at grade-school children growing up in inner cities. He traveled around the country relentlessly to promote it, and eventually won the official endorsement of the Children’s Television Workshop of Sesame Street fame, as well as the lifelong friendship of one of the most important figures there, Chris Cerf. That’s just the way it was with Preiss throughout his life. He seemed genuinely unaware of the barriers between him and the people of power who could realize his dreams, and in consequence they seemed to just melt away. His gifts for gab and inspiration were legendary, as recalled by Leigh Ronald Grossman, one of a stable of young writers he came to nurture:

He had to be the most passionate person I’ve ever known, able to visualize what was special and exciting about EVERYTHING. I remember going to lunch with Byron and another publisher, in which the discussion hinged on a tired project that the whole staff was sick of dealing with after years of development. By the end of the lunch I was thrilled to be working on such a visionary project… and I’m still not quite sure how he did it.

He founded his own publishing company, Byron Preiss Visual Publications, in 1974 while enrolled in the film program at Stanford University. Through it he designed and/or published a variety of interesting, often groundbreaking work: a line of paperbacks that tried to revive the pulp adventures of the 1930s more than five years before Raiders of the Lost Ark; adult comics that didn’t involve superheroes and were forerunners of what have come to be called “graphic novels” today; Dragonworld, a beautifully illustrated epic fantasy novel which he himself coauthored; The Illustrated Harlan Ellison, whose pictures were in 3D and could be viewed through a pair of 3D glasses bound into the volume; various profusely illustrated nonfiction volumes for children and adults, on subjects ranging from the Beach Boys to dinosaurs. Throughout he assiduously cultivated relationships. By the time he turned thirty, Preiss’s Christmas-card list included people like Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, the aforementioned Harlan Ellison, and Ray Bradbury in addition to many of the biggest names in the business of publishing and, yes, the members of the Beach Boys as well. C. David Seuss (a man whose role in this story will become clear shortly) believes that his sheer likability was perhaps his biggest asset of all; “people just wanted to go along with his ideas because he was just so nice.”

Throughout his career Preiss pushed the boundaries of what a book could be — physically, formally, and aesthetically. It’s thus little surprise that he got involved when the idea of the interactive book began to emerge in earnest in the early 1980s. His first project was a unique series in the crowded field of Choose Your Own Adventure books and copycats that dominated the children’s sections of bookstores at the time. The Be an Interplanetary Spy series mostly replaces simple choices of the “what do you want to do next?” variety with visual and logic puzzles that have to be solved to advance the narrative. In keeping with the through-going theme of Preiss’s career, the books are also lavishly illustrated, to the point that they are more interactive comic book than conventional text; the illustrations are often more important than the words. He would later create two more traditional but also fondly remembered gamebook series, Time Machine and Explorer.

Preiss had been well aware of computers and computer games since the mid-1970s, when like so many other Stanford students he paid a visit to nearby Xerox PARC. By mid-1983, with home computers booming, he felt the time had come to get involved with them as yet another facet of what a book could be. Indeed, the Be an Interplanetary Spy books, which started to appear at just this time, show more than a hint of influence from games like those of Infocom in their many puzzles and their replacing the occasional choices of Choose Your Own Adventure with almost constant interaction. By packing three or four puzzles and narrative branches onto almost every page he was able to make the books feel less granular, more like a parser-based adventure game than a Choose Your Own Adventure book. Still, Preiss wanted to go further. He started shopping around an idea for a series of computer games based on works by established authors, many of whom he just happened to have personal relationships with and whose participation — or at least willingness to sign a licensing contract — he could thus all but assure. He found himself a dance partner in the aggressive young Spinnaker Software.

Founded in April of 1982 by two friends from Harvard Business School and the Boston Consulting Group, Bill Bowman and C. David Seuss, Spinnaker was, like Electronic Arts, one of the new guard of slicker, more conventionally professional software publishers that began popping up during 1982 and 1983. Neither Bowman nor Seuss had a hackerish bone in his body. For proof, one need look no further than the ties they insisted on wearing to work every day at Spinnaker, or Bowman’s habit of getting up at 5:30 every morning to attend mass, or his seven children that were often hovering around Spinnaker’s offices after school hours (a marked contrast to life at Infocom, populated mostly by childless twenty- and thirty-somethings). They were savvy businessmen who saw an opportunity to get in on the ground floor of an emerging market after the arrival of the IBM PC (Bowman believes he has one of the first hundred ever built) and the wave of purpose-built home computers that was set off by the Commodore VIC-20. The legendary venture capitalist Jacqueline Morby funded a nationwide jaunt to talk to retailers and look for obvious holes in the market, which revealed an exploding demand for educational software that could not be met by under-capitalized semi-amateurs like Edu-Ware. They jumped at it, with the aid of millions in venture capital arranged by Morby and her company TA Associates. (Morby would also take a place on Spinnaker’s board, along with that of Sierra On-Line and several others, making her one of the most powerful hidden shapers of the software industry of the 1980s.)

Spinnaker released their first products just in time for the Christmas of 1982. Some were done in-house, some by outside developers like educational pioneer Tom Snyder Productions. Quality inevitably varied, but some, like Snyder’s In Search of the Most Amazing Thing, have become children’s classics. Still, Spinnaker was emblematic of the changes that swept the software industry with the the home-computer boom and the arrival of traditional big-business interests — and big-business money — looking to capitalize on it, yet another sign that the era Doug Carlston referred to as the software “Brotherhood” was well and truly ended. Their agenda plainly included driving older rivals like Edu-Ware out of the market entirely, a goal they soon accomplished. They placed all but unprecedented emphasis on licensing, branding, and advertising, a result of what Seuss calls his “First Law”: “Apply money at the point of resistance.” Spinnaker poured some 15% of their total earnings for 1983 back into huge advertising buys, much of it outside the trade press in places like Good Housekeeping, Better Homes and Gardens, and Newsweek. They soon hit upon the scheme of releasing their software under a number of sub-brands, each of which would be as often as possible a licensed take on an already well-known consumer entity. By the end of 1983 their stable already included Fisher-Price (educational software for the very young; name licensed from the huge toy company), Nova (science education; name licensed from the long-running PBS television series), and Better Living (personal productivity software), as well as the flagship Spinnaker brand. Whatever its other merits, the approach was a clever sleight of hand for a company that aimed to do nothing less than own educational software, and in time and with luck to extend that dominance to home-computing software as a whole. Bowman:

“Shelf space is all that matters in this business. If everything is under the Spinnaker brand, the consumer feels he’s not getting much of a choice, but here he can choose any of six brands.”

Feel free to put your own scare quotes around “choose” there. Spinnaker drew analogies between themselves and General Motors, who had their Buick, Chevrolet, Oldsmobile, etc. — if nothing else an indication that Bowman and Seuss weren’t afraid to dream big. When Byron Preiss came along with his idea for a new line of bookware, it was both an opportunity to add yet more brands to the stable and to begin to make inroads into entertainment software (something that had been on their long-term agenda from the start), just as the Better Living brand represented their first explorations of the productivity market. Their internal industry studies showed adventure games to be a very good place to start. While they currently sold in less than one-third the numbers of action games, the segment was growing rapidly, while action games were doing just the opposite.

Shortly after Preiss came on the scene, one of Spinnaker’s best outside developers, Dale Disharoon, came to them with a bookware idea of his own: to make edutainment based on classic and contemporary children’s books. Disharoon’s educational titles sold in huge numbers for Spinnaker, so when he talked they tended to listen. Thus was born the Windham Classics line, brand number six for Spinnaker, as a companion to Trillium.

Preiss was most closely involved with the latter, and that’s also where we’ll be spending most of our time. As should be clear by now, Trillium owed its existence to a mixture of artistic idealism and commercial pragmatism — not that such strange bedfellows aren’t pretty much business as usual in any media industry. For Preiss, Trillium represented nothing less than the future — or a possible future — of fiction. For Spinnaker, it represented a bit of the same but also yet another branding opportunity, the chance to stamp the names of popular authors onto boxes and get in on the hot new trend in entertainment software. They placed a young marketer named Seth Godin in charge of Trillium’s image. (Godin has since gone on to a career as a prominent marketing guru.) Now it was time to start rounding up authors.

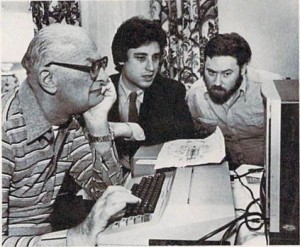

Here Preiss proved the value of all those connections to the world of written science fiction. He pulled out his thick phone list and started calling some of the name authors with whom he’d carefully built relationships over the last decade. He soon had Arthur C. Clarke signed for an adaptation of Rendezvous with Rama and Ray Bradbury for Fahrenheit 451. He also reached a tentative agreement with Robert Heinlein to adapt his juvenile classic Starman Jones, and initiated talks with Roger Zelazny, Philip José Farmer, Harry Harrison, and Alfred Bester. As with most of the products of the era of bookware, the question of how involved these authors were actually willing to be was always a delicate one. Mostly they wound up doing little more than politely sitting through presentations of the latest versions, with their creative role amounting to little more than a never- or almost never-exercised veto power. And that was about it, beyond signing their name to an appropriately glowing endorsement for the back of the box. Only Ray Bradbury was willing to get somewhat more involved, actively drawing up plot ideas for and by reports even contributing some prose to the Fahrenheit 451 game.

Thus when Spinnaker approached Michael Crichton about adapting one of his books, they must have been thrilled to learn that Crichton had already been working on an original game with some associates for eighteen months, and was in fact looking for a publisher. More problematic was a game called Shadowkeep, a text-adventure/CRPG hybrid offered to Spinnaker by a small developer called Ultrasoft. A book or an author was nowhere in sight, but it was just too impressive a game to pass up, so Spinnaker simply flipped the process on its head by hiring Alan Dean Foster, the reigning king of media tie-in novels (he had made his name in the industry by ghost writing the novelization of the original Star Wars for George Lucas), to write a book based on the game. He would thus have his name displayed in huge letters on the box of a game he had had absolutely nothing to do with. For the Windham Classics line, Spinnaker took advantage of some blessedly out-of-copyright children’s classics like The Swiss Family Robinson, Treasure Island, Alice in Wonderland, and The Wizard of Oz, but did sign a license for the recent Green Sky Trilogy, whose author, Zilpha Keatley Snyder, did heavily involve herself in the design of the resulting game. That game, Below the Root, is not a text adventure at all but is a lovely, lyrical classic in its own right.

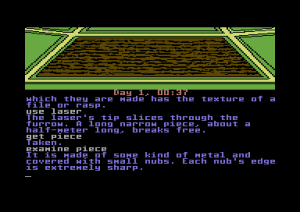

Indeed, the games of Trillium and Windham Classics take a surprising variety of approaches, mixing illustrated text adventure with action and CRPG elements, sometimes in the same game. But the fundamental goal, particularly for the Trillium games, was to outdo Infocom at their own game. Largely at Seth Godin’s behest, Spinnaker put the Trillium games inside mouth-wateringly beautiful gatefold boxes that on aesthetic grounds might just outdo — dare I say it? — Infocom. They also started a newsletter in an effort to build a community of loyal customers in the same way Infocom had, although they were a bit stumped as to what to put in it beyond plugs and order forms for the games; Spinnaker’s offices weren’t filled with the same sort of inspired madness that made The New Zork Times such a constant delight. Infocom couldn’t help but feel the target Spinnaker had plainly painted on their back, couldn’t help but feel a bit unnerved by this big company — already much larger than them — with their big-name authors and their illustrations and other additional gimmicks that was determined to wrest away from them their comfortable niche in the industry. Spinnaker even negotiated a deal to get the Trillium games into every Waldenbooks in the country to sit side by side with the Infocom games that had also just arrived there thanks to Infocom’s deal with Addison Wesley. Various Infocom folks have quietly acknowledged that Spinnaker was the only competitor who ever really made them nervous in 1984, the year they sold more games than in any other.

They thus must have been quite pleased when the Trillium line hit a major snafu within weeks of launching in the fall of that year. It seemed there already existed a tiny publisher of educational books using the name of “Trillium.” Now the original Trillium’s lawyers came calling. Seuss feels they could have fought the suit and likely prevailed (the original Trillium had never actually registered their name as a trademark), but it would have been time consuming, disruptive, and expensive. Spinnaker chose instead to start the embarrassing process of re-branding the entire line with a new name. They chose “Telarium,” a name that, for what it’s worth, I like a lot better anyway. (To avoid confusion as we crisscross the Trillium/Telarium split in this and future articles, I’m just going to refer to the brand as “Telarium” from now on.)

The whole debacle was anathema to a company that was so focused on branding. And it was almost as frustrating when negotiations with the Heinlein people to release Starman Jones, previously considered a done deal to the extent that a huge amount of work had already been done on the game, reached an impasse from which they would never emerge despite months and months of Telarium’s optimistically announcing the nearly completed Starman Jones as “coming soon.”

The arrival of Telarium was greeted with hostility and even a certain amount of contempt, not only at Infocom but amongst their other peers as well. Jon Freeman, never one to pull his punches, delivered a withering takedown via his column in Computer Gaming World:

In the first place, the economics of the situation almost guaranteed that the programmers involved, despite the hype, would not be first-class. Big Name Authors and Best-Selling Books don’t come cheap. Although the draw of author and book is clearly a marketing advantage — and should therefore be paid out of the marketing/advertising budget — the cost is normally borne by R&D. A big chunk of the royalties that would otherwise go to the developers of the game is paid, instead, to the author of the book. What top-flight game designer or programmer would take that kind of a pay cut? Regardless of their deficiencies as game designers, most good programmers are still at work on their own ideas. Those who can’t come up with original subjects for games are busy making a lucrative living converting popular games to new computers. Therefore, the majority of programmers available for these book projects are either inexperienced or inadequate or both.

The worst part is that the SF people involved don’t know how little they know about the subject. Few of the authors involved in all these projects play games: most lack the time; many lack the inclination. Technophobes like Ray Bradbury, who admits that he cannot use the computer he owns, believe the apex of computer usage is to enter the text of a book and read it on the CRT. Would he know a good computer game if he fell over one?

Yes, Freeman’s logic is questionable at best. Still, many of the people who had been in the industry for years saw Telarium as calculated and soulless, and not without cause. There was an air of contrivance, even perhaps a note of disingenuousness about the whole enterprise. Seth Godin claimed, “We wanted to go to the people who could write [the games] the best. And that’s not programmers — it’s authors.” Which would be fine if only the authors in question were actually deeply involved; witness the particular absurdity of Shadowkeep as an “Alan Dean Foster” game. Meanwhile Telarium’s addition of graphics and music and even action sequences to the Infocom template just screamed of bullet points on some marketer’s demands for more, more, more than the competition. When the line ultimately proved commercially disappointing, few felt much sympathy. In fact, they cheered the failure as an object lesson that you can’t buy your way to success with big licenses and an overstuffed marketing budget. (A lesson subsequent gaming history has not, alas, always borne out.)

Yet there was also, as I’ve already noted, that idealistic side to Telarium that hasn’t been discussed enough. A genuine aesthetic vision drove Telarium — a vision for games as coherent lived fictional experiences. Byron Preiss:

“We’re trying to make a game that is based on plot and characterization, not puzzles — the way a book is. If you read Fahrenheit 451, you don’t get stuck on page 50. And if you play the game, you don’t get stuck on frame 50, because the whole idea is that you’re interested in the game because of the characters and the plot and what’s happening. You care about what’s going on.”

Or, as he put it another way: “When you’re reading a good book, say a Ludlum thriller, you’re really sweating because you believe you’re part of the story. Adventure games weren’t doing that because the puzzles kept bringing you back to reality.” People in and around Telarium expressed over and over this determination to get beyond arbitrary, often frustrating set-piece puzzle solving to something worthy of Infocom’s chosen label of interactive fiction. To what extent they succeeded is debatable; certainly the games have plenty of rough edges. Still, they’re also more than worthy of the sort of careful second look that too few of the non-Infocom works of the bookware era have heretofore received. We’ll begin the process of remedying that next time.

(Many thanks to C. David Seuss for answering questions and sharing his memories with me. A Harvard Business School case study on Spinnaker was also invaluable. Particularly good contemporary articles on Telarium and the bookware phenomenon are in: the September/October 1983 Softline; the December 1984 Compute!’s Gazette; the June/July 1985 Commodore Power Play; the February 1985 Compute!; the April 1985 Electronic Games; the June 18, 1984 InfoWorld; the July 30, 1984 InfoWorld; the August 13, 1984 InfoWorld; the August 1984 Computer Gaming World; the February 1985 Micro-Adventurer; and the May 1985 Commodore Microcomputers. All were used for this article and the ones on individual Telarium games that will follow, as were Jason Scott’s Get Lamp archives which he kindly shared with me. The great illustration that begins this article was taken from the April 1985 Electronic Games.)