(I was never happy with this article in its original form, so I’ve added coverage of The Scoop to that of Breakers and moved it to here in the blog’s chronology, where I feel it makes a better fit. Don’t worry, Nate, I’ve preserved your comments. Patreon subscribers: you of course won’t be charged for this one.)

As we push now into 1986 in this blog’s chronology, we’re moving into an era of retrenchment but also of relative stability, as the battered survivors of the home-computer boom and bust come to realize that, if they’re unlikely (at least in the short term) to revolutionize mainstream art and entertainment in the way they had expected, home computers and the games a relatively small proportion of the population enjoy playing on them are also not going to go away. A modest but profitable computer-games industry still remained following the exit of the pundits, would-be visionaries, and venture capitalists, one that would neither grow nor shrink notably for the rest of the decade. No longer fixated on changing the world, developers — even the would-be rock stars at Electronic Arts — just focused on making fun games again for a core audience that loved Dungeons and Dragons, Star Wars and Star Trek, and ships and airplanes with lots of guns on them. While publishers would continue to take a chance on more outré titles than you might expect, much that didn’t fit with this core demographic that stuck with gaming after the hype died began now to get discarded.

Amongst the victims of this more conservative approach were bookware and the associated dreams for a new era of interactive popular fiction. Bookware had, to say the least, failed to live up to the hype; the number of commercially successful bookware titles from companies not named Infocom could be counted on one hand and likely still leave plenty of fingers free. Small wonder, as the games themselves were, if often audacious and interesting in conception, usually deeply flawed in execution, done in by a poor grasp of design fundamentals, poor parsers and game engines, rushed development, and an associated tendency to undervalue the importance of playtesting and polishing for any interactive work. One could say with no hyperbole whatsoever that Infocom was the only company of the 1980s that knew how to consistently put out playable, enjoyable, fair text adventures — meaning I’ve spent a great deal of time and energy in the years I’ve been writing this blog merely confirming this conventional wisdom, but so be it.

Thus bookware faded quietly away, done in both by gamers who were not terribly invested in games as literature and its own consistently inconsistent quality control. Whether better works could have brought the former around, or found a new audience entirely, remains a somewhat open question. But as it was, one by one the bookware lines came to an end. Bantam’s Living Literature line stopped after just two titles; the Mindscape/Angelsoft line made it all the way to eight; other publishers like Activision, Epyx, and Electronic Arts abandoned the genre after one or two experiments failed to bear commercial fruit. And the most notable of all the bookware lines and certainly the ones we’ve spent the most time with, the Brøderbund/Synapse Electronic Novels and the Telarium games, were also not long for this world.

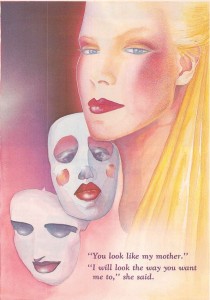

Breakers, written by a friend of the Synapse boys named Rod Smith, was the fourth and last of the Electronic Novels to be released. It’s also the largest, most complex, and most difficult — albeit mostly not in a good way. Breakers places you aboard a ramshackle space station in orbit around a planet called, I kid you not, Borg, proof that there’s a limited supply of foreboding names in the universe. It’s somewhat unusual as both science fiction and interactive fiction in being told from the point of view of an alien who’s not just your typical Star Trek-style human with different skin pigmentation or unusually formed ears. The Lau, the race to which you belong, are residents of Borg whose culture is mystical rather than technological, who communicate via telepathy. They’re now being punished for their disinterest in warfare by being rounded up and sold off as exotic slaves to customers all over the galaxy by many of the unsavory characters who inhabit the station. Meanwhile a cosmic apocalypse is in the offing which only the Lau can prevent by assembling four elements and performing a ritual. By happenstance, you’ve ended up loose on the station. You must assemble the elements to save your race and avert the catastrophe; even a text adventure that fancies itself an electronic novel often winds up a treasure hunt.

That said, the Electronic Novels seldom lacked for literary ambition, and Breakers is no exception. Smith does a pretty good job of showing the crazy cast-offs, pirates, and rogues — some with the proverbial hearts of gold, most responding to overtures only with laser blasts — from the standpoint of an apparently asexual and very alien alien. If not quite up to the standard of Lynnea Glasser’s recent, lovely interactive fiction Coloratura, it is interesting to view Breakers‘s stock-science-fiction tropes from this other, exotic point of view. The opening scene in a seedy bar filled with thumping music and humans and aliens of every description is unexpectedly compelling when viewed from the perspective of this protagonist despite being thoroughly derivative of a certain 1977 blockbuster.

All sorts of issues of technology and fundamental design, however, cut against the prospect of enjoying this world. The opening section of the game, inside that seedy bar, is so baffling that a magazine like Questbusters, one of the few with enough remaining interest in the Electronic Novel line to write about Breakers at all, dispensed with any semblance of graduated hints and just printed a walkthrough of the opening sequence — one that, tellingly, appears to rely on a bug, or at least a complete plotting non sequitur, to see it through. Smith had wanted to make Breakers rely heavily upon character interaction, a noble if daunting goal. In practice and in light of the problematic Synapse parser, however, that just leads to a series of impossible dialog puzzles that require you to say the exact right sequence of things to get anywhere. While the plot is unusually intricate, it’s essentially — if as-advertised in light of the “Electronic Novel” label — a novel’s plot, a series of linear hoops that require you to just slavishly recreate a series of dramatic beats, even when doing so requires that you deliberately get yourself captured and beat up. But, unlike in most linear games, you never know what the game expects next from you, leading to an infuriating exercise not so much in saving Borg as in figuring out what Smith wants to have happen next and how you can force it to take place.

Breakers was released by Brøderbund in a much smaller, much less lavish package than its predecessor, complete with cheesy art that looked cut out of an Ed Wood production. The Synapse name, which studio Brøderbund was now in the process of winding down as an altogether disappointing acquisition, is entirely absent from the package, as is even the old “Electronic Novel” franchise name, although it remains all over the manual from which it would presumably have been harder to excise. The game is now just a “text adventure” again, a circle closed in ironic and very telling fashion.

So, Breakers would mark the end of the line for this interesting but frustrating collection. Reports from former Synapse insiders have it that a fifth Electronic Novel, a samurai adventure called Ronin, was effectively complete by the end of 1986. But it was never released. Two more with the intriguing titles of Deadly Summer and House of Changes also had at least some work done on them before Brøderbund pulled the plug on the whole affair. My inner idealist wishes he’d had a chance to play these games; my inner cynic knows they’d likely have been undone by the same litany of flaws that make all of the released Electronic Novels after Mindwheel disappointing to one degree or another.

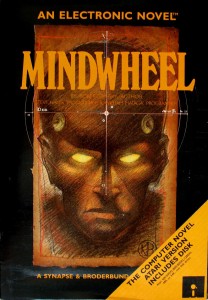

The final game in Spinnaker’s Telarium line, The Scoop, stands along with Shadowkeep as one of the two oddballs of that bunch. Its choice of source material alone is a rather strange one. As you can see from the box image above, Telarium did their best to portray The Scoop as a product of Agatha Christie. However, the original The Scoop isn’t actually an Agatha Christie novel. It’s rather an artifact of the Detection Club, a sort of casual social club of cozy mystery writers that still persists to this day. Six writers — Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, E.C. Bentley, Anthony Berkeley, Freeman Wills Crofts, and Clemence Dane — passed the manuscript in progress among themselves by post. It came to each twice, whereupon he or she added a chapter to the unfolding story and sent it on to another. Later each read their chapters live on BBC Radio, the organization that had commissioned the whole project in the first place. The installments also appeared in the BBC’s magazine, The Listener, before being eventually published in book form. Interesting as it is as an early experiment in collaborative narrative, the final product reads pretty much exactly like the patchwork creation it is, with a plot that zigs and zags in wildly divergent directions according to each writer’s whim. It’s remained only sporadically in print since its original publication in 1931, a curious piece of ephemera for hardcore Christie fans and aficionados of golden-age mystery.

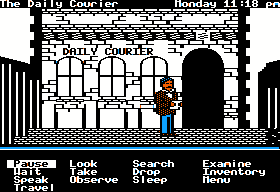

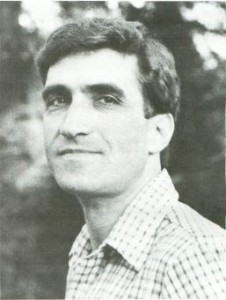

The game engine of Telarium’s version of The Scoop makes it stand out from its peers as much as its unusually obscure literary inspiration. Like Shadowkeep, The Scoop was developed by an outside developer rather than in-house, and thus doesn’t use the SAL engine that powers most of the other games. Said developer was Dale Disharoon, Inc., a tiny collective founded by the eponymous former grade-school teacher in 1983 to produce more polished versions of the educational software he had started writing for his class a couple of years earlier. Disharoon enjoyed a close relationship with Spinnaker for quite some time, one that led most notably to the gentle adventures Below the Root (1984) and Alice in Wonderland (1985). Both were largely designed and programmed by Disharoon himself and published through Windham Classics, Spinnaker’s other bookware label for children’s literature adaptations targeting a slightly younger age group than the Telarium games. Thus it must have seemed a good idea to give him a crack at making The Scoop using a superficially similar engine to the one behind Below the Root and Alice, which replaced the SAL parser with a menu-driven command system. Busy with other projects, Disharoon turned The Scoop over to writer and designer Jonathan Merritt, programmer Vince Mills, and artist Bill Groetzinger. To give them extra space to play, Spinnaker agreed to leave behind the lucrative Commodore 64 platform and release The Scoop only for machines with at least 128 K.

Alas, though, the idea sounded a lot better than it would end up playing. The mid-1980s were an era marked by widespread interface experimentation in adventure-game design, as developers tried to figure out what the logical successor to the parser should be. To its credit, The Scoop doesn’t really feel, as do many of its contemporary peers, like a traditional text adventure with a menu system grafted on. It actually sports a pretty good interface, with a reasonable selection of verbs always easily accessible at the tap of a space bar. Unfortunately, the game to which it’s grafted is just kind of baffling, and not in a good way. This is one of only two Telarium games that settles for simply recreating its source material’s plot, rather than finding some way to do an end run around the problem of player advance knowledge like most of its peers. Perhaps the developers figured its source material was obscure enough that few players would be familiar with it anyway. And indeed, in the end it doesn’t much matter; I dutifully read the novel to prepare myself for the game, and I still didn’t get much of anywhere with the latter. For one thing, the rather thin plot of the novel has been greatly expanded, with lots of new characters and evidence and several new sub-plots, although the big picture at the end is the same. But that wasn’t the real source of my frustrations.

You see, an expanded plot would have been welcome if the game was actually fun, but it really isn’t. This is one of those mystery games that hinges on timing. A cast of literally dozens wanders all over an expansive map of London and nearby environs over the five days or so that the game gives you to solve it. You have to dog each and every one of them relentlessly, eavesdropping on conversations and searching every locale as soon as they leave it, to get anywhere. Once you’ve collected all the individual jigsaw pieces, you can presumably restart one last time and unspool “The Mystery of the Mindreading Detective.” I don’t mind this sort of thing in some other games, but here there’s some secret sauce missing. All of the waiting around and the fiddly searching is just tedious, the writing flat and the characters bland. And the feedback loop is badly untethered at one end. You never really know where you stand with the game, never know if it knows you know what you think you know — a problem that’s admittedly all too common in ludic mysteries. Nor is it clear what you’re supposed to do to tell the game about it once you think you’ve solved the case. With little idea of whether what I was doing and learning meant anything or not, with the constant well-justified paranoia that I was missing something important somewhere else, I spent my time in The Scoop in a discombobulated haze. Finally I just gave up.

Which as it happens is exactly what Spinnaker was doing with the Telarium line in 1986. By that year the company was in serious trouble, having bet big like so many others on a home-computer revolution that never quite arrived and lost badly. Spinnaker had had a negative bank balance for the last two years, and one of its co-founders, Bill Bowman, had already bailed, leaving C. David Seuss struggling to make payroll by exercising stock options. The company was, as Seuss puts it, “flat broke.” Then, looking around the market, Seuss spotted what he calls a “point of discontinuity”: a new generation of IBM PC clones like the Tandy 1000 that were for the first time packaged and priced to be attractive to buyers outside corporate America. With little else going for Spinnaker, Seuss elected to “bet the company” on that emerging market. Managing to pull together some capital by calling on Harvard University connections, he applied Spinnaker’s remaining staff to creating a new line of home-office and small-business productivity software. Spinnaker 2.0 would be, like Activision 2.0, a shadow of its old self for some time, but sales would eventually rebound from a low of $8 million in 1987 to $65 million in 1994, the year Seuss sold the company to The Learning Company.

The Telarium and Windham Classics lines were among the inevitable casualties of Seuss’s new strategy. They were quietly cancelled, the remaining stock sold off at fire-sale prices. The Scoop was already complete, with packaging created and promotion efforts already begun, when the fateful decision came down. It was thus never actually released… until, that is, 1989, when a somewhat rejuvenated Spinnaker decided to give it a go after all under their own imprint for the Apple II and MS-DOS (a Commodore 128 version that had been announced back in 1986 never did arrive). A less than spectacular game now three years behind the times in the graphics and interface departments, The Scoop attracted little notice and quickly fell out of print again, the last gasp of this line of often botched but frequently fascinating games. Ah, well… the anticlimax that was The Scoop‘s belated release does at least let us reassure ourselves that it wasn’t a cancelled masterpiece. We don’t know for sure, on the other hand, what would have come from other ongoing or proposed Telarium projects based on novels by Robert A. Heinlein, Philip Jose Farmer, and Harry Harrison — although, as with the Synapse games, it seems unrealistic to imagine that they wouldn’t have suffered from Telarium’s usual litany of problems.

The fate of completed titles like The Scoop and Ronin, which their publishers judged not capable of recouping the additional expense of actually releasing them, tells you just about all you need to know about the commercial state of bookware by 1986. And it only takes a good look at Breakers and The Scoop to understand much about the fundamental issues of design and technology that plagued the vast majority of the bookware releases. They serve as good examples of a format that went out much like it came in, full of big notions but also a bit half-baked. In the interest of history if nothing else, feel free to download The Scoop and Breakers and give them a try. The former is in the Apple II version; the latter in the MS-DOS version, and includes a DOSBox configuration that should work very well.

(My thanks go to C. David Seuss for sharing memories and documents relating to Spinnaker’s history. Dale Desharone, né Dale Disharoon, died in 2008. He was interviewed by Hardcore Gaming 101 shortly before his passing. A much older profile can be found in the November 1983 Compute!’s Gazette.)