While the Apple Macintosh, Atari ST, and Commodore Amiga weren’t exactly flying off American store shelves in 1985 and 1986, they at least had the virtue of existing. The British computer industry, by contrast, proved peculiarly unable to produce 16-bit follow-ups to their 8-bit models that had made Britain, measured on a per-capita basis, the most computer-mad nation in the world.

Of the big three in Britain — Sinclair, Acorn, and Amstrad — only Sinclair really even tried to embrace the 16-bit era on a timely basis, announcing the QL the same month of January 1984 that the Mac made its debut. They would have been better off to wait a while: the QL was unreliable, ill-thought-out, buggy, and, far from being the “Quantum Leap” of its name, was still mired in the old ways of thinking despite its shiny 68008 processor, a cost-reduced variant of the one used by the Apple Macintosh. It turned into a commercial fiasco, and Sinclair never got the chance to try again. Torpedoed partly by the QL’s failure but more so by a slowdown in Spectrum sales and Sir Clive’s decision to pull millions of pounds out of the company to fund his ridiculous miniature-television and electric-car projects, Sinclair came within a whisker of bankruptcy before selling themselves to Amstrad in 1986.

Acorn, meanwhile, gave their tendency to overengineer free rein, producing a baroque range of new models and add-ons for their 8-bit BBC Micro line while its hugely ambitious 32-bit successor, the Acorn Archimedes, languished in development hell. Undone by the same slowing market that devastated Sinclair as well as by an ill-advised grab for the low-end in the form of the Acorn Electron, Acorn was also forced to sell themselves, to the Italian company Olivetti.

That left only Amstrad still standing in an industry that had been just a year or two before the Great White Hope of a nation, symbol and proof of concept of Margaret Thatcher’s vision of a new, more entrepreneurial and innovative British economy. Unfortunately, Amstrad’s founder Alan Sugar just wasn’t interested in the kind of original research and development that would have been required to launch a brand new machine based on the 68000 or a similar advanced chip. His computers, like the stereos he had been selling for many years before entering the computer market, were all about packaging proven technology into inexpensive, practical products for the masses. There’s something to be said for that sort of innovation, but it wasn’t likely to yield a Macintosh, an Amiga, or even an Atari ST anytime soon.

This collective failure of the domestic makers meant that British punters eager to experience the wonders of 16 bits were forced to look overseas for their new toys. Yet that was a fairly fraught proposition in itself. The Macintosh was practically a machine of myth in Britain for years after its American debut, absurdly expensive and available only through a handful of specialized shops. Only wealthy gentlefolk of leisure like noted Mac fanatic Douglas Adams could contemplate actually owning one. And the Amiga, not even available in Britain until June of 1986, also suffered even thereafter from an expensive price tag and poor distribution.

That left the Atari ST as the only really practical choice. The situation was a surprising one in that Atari had not traditionally been a big player in Britain. The Atari VCS game console that had left its mark on the childhood of an entire generation in North America was virtually unknown in Britain, and, while Atari’s line of 8-bit computers had been nominally available, they had been an expensive, somewhat off-kilter choice in contrast to the Sinclair Spectrums and Commodore 64s that outsold them by an order of magnitude. But Jack Tramiel, previously the head of Commodore and now owner of the reborn post-Great Videogame Crash Atari, knew very well the potential of the European market, and pushed aggressively to establish a presence there. In fact, the very first STs to go on sale did so not in the United States but rather West Germany. By the end of 1985 STs were readily available in Britain as well and, at least in contrast to the Macintosh and Amiga, quite inexpensive. A British software industry looking for a transformative machine to lift home computing in Britain out of its doldrums placed its first hopes — admittedly largely by default — in the Atari ST.

Still, it was far from clear just what sort of form the hoped-for new ST software market would take. The ST may have been a bargain in contrast to the Macintosh and Amiga, but it was still a fairly expensive proposition within a country just getting back on its economic feet again after what felt like decades of recessions, shortages, and labor unrest. A reasonably full-featured ST system could easily reach £1000, many times what one could expect to shell out for the likes of a cheap and cheerful Speccy. The ST would seemingly need to attract a different sort of buyer, with more money to spend and perhaps a few more years under his belt. This expectation was one of the calculations that led to Rainbird, one of the most significant British software houses of the latter 1980s.

Rainbird was born from Firebird, a slightly older label that has plenty of significance in its own right. In 1984 British Telecom, solely responsible at the time for the telecommunications grid of all of Britain, was privatized, becoming a huge for-profit corporation as part of Margaret Thatcher’s general rolling-back of the socialist wave that had followed World War II. Even before the first shares were sold to the public on November 20, 1984 — the largest single share issue in the history of the world at the time — the newly liberated management of British Telecom began casting about for new business opportunities. It didn’t take them long to notice the exploding market for home-computer software. They thus formed a new division of Telecomsoft, whose first imprint was to be called “Firefly Software.” That name was quickly changed to “Firebird” — it seems marketing manager James Leavey had just been listening to Stravinsky’s The Firebird — when they discovered a potential trademark conflict with another company. Firebird made its public bow in time for Christmas 1984 with a whole raft of mostly simple action games, selling for £2.50 (Firebird “Silver”) or £6 (Firebird “Gold”). Many turned into bestsellers.

Whether you considered British Telecom’s entrance into software a necessary result of a rapidly maturing industry or you were like Mel Croucher of Automata in considering them nothing more than “parasites” on software’s creative classes, it marked a watershed moment, a definitive farewell to the days of hobbyists meeting and selling to one another at “microfairs” and a hello to a hyper-competitive, corporatized industry destined someday to be worth many billions. If anyone was still in doubt, in December of 1984 another watershed arrived when newly minted software agent Jacqui Lyons presided over an unabashed bidding war for the right to publish Ian Bell and David Braben’s Elite on platforms other than the BBC Micro. Firebird, with the deepest pockets in the industry by far, won the prize.

Although published on the Firebird label, Elite would prove to be something of a model for the eventual Rainbird. Unlike Firebird’s previous releases, which had used the colorful but minimalist packaging typical of British games at the time, Elite‘s big, sturdy box contained not just the cassette or disk but also a thick manual, an equally thick novella to set the stage, a glossy quick-reference card, and a poster-sized ship-recognition chart (all licensed and reproduced from the Acornsoft original). All this naturally came at a price: £15 for the cassette version, fully £18 for the disk version. It marked a new way to sell games in Britain: as luxury products aimed at a classier, more sophisticated, perhaps slightly older consumer. In spite of the extra cost of all that packaging, the profit margins on its higher price points were to die for. If the Elite approach could be turned into a sustainable line rather than a one-off, British Telecom just might have something.

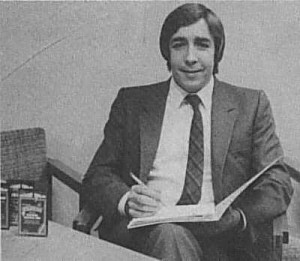

One person inside British Telecom who paid a lot of attention to Elite‘s launch and its subsequent success was Tony Rainbird, a former software entrepreneur in his own right who now worked for Firebird. He began agitating his superiors for a new software label, a sort of boutique prestige brand that would sell more sophisticated experiences at a correspondingly higher price point; it would be, if you can forgive an anachronistic metaphor, the Lexus to Firebird’s Toyota. His thinking was influenced by a number of factors in addition to Elite‘s success. He was very aware of the Atari ST that was then just arriving in Britain, aware that the people who bought that machine and in the fullness of time its inevitable eventual competitors would be willing and able to spend a bit more for software. And he was very aware of the American software market, which at that time was enjoying a golden age of gorgeous game packaging thanks to labels like Infocom, Origin, and Telarium. Games from those publishers and many others in the United States were marked by high concepts, high prices, and, yes, high margins to match. Elite, the first British game that could really compete in the United States on those terms, had been the first game that Firebird exported there; it became as huge a hit in the United States as it had in its native country. A new luxury imprint could continue to export games and other software that suited the higher expectations of Americans, whilst trading on the slight hint of the exotic provided by their British origins.

After getting permission to give the new line a go, with he himself at its head, Tony Rainbird decided that all the games should be published in distinctive boxes done in a deep royal blue, a color which to him exuded class. His first choice for a name was “Bluebird Software.” But, once again, a search turned up a conflict with another trademark, so he allowed himself to be persuaded to give the line his own name. Just as well; it fitted even better as a companion to the Firebird line.

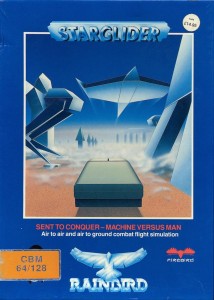

Rainbird was launched quietly at the end of 1985 with two 8-bit creativity titles, The Art Studio and The Music System, that echoed more than faintly Electronic Arts’s Deluxe line of high-toned creative applications in the United States. But it was the following year that saw things get started in earnest, with two splashy game launches for the Atari ST. One of these, The Pawn, is an adventure game we’ve met before, along with its maker Magnetic Scrolls; we’ll continue their story in the next article I write. It’s the other, a space shoot-em-up called Starglider, that I want to spend just a bit of time with today. It’s not really a great game, but it is an interesting one to consider in its historical context, not least because of the colorful history of the person who wrote it, a young hacker with the perfect videogame-character name of Jez San (“Jez” is a nickname for “Jeremy”).

Jez San had already had a greater impact on British computing before his twentieth birthday than most programmers manage in a lifetime. It all began when his father, owner of a successful import/export firm, gave him an American TRS-80 computer in 1978, when he was not quite thirteen years old. He first won attention for himself by coming up with a hack to let one attach the joystick from an Atari VCS — another piece of foreign exotica that came to him courtesy of his father’s business — to the TRS-80 for playing games in lieu of the awkward keyboard controls that were the norm. His skills had progressed so far by 1982 that his father agreed to become partners with him in a little software-development company to be called Argonaut Software — think “J. San and the Argonauts” — run out of his bedroom. Whilst writing software for whomever would pay him, San was also soon terrorizing the network of British Telecom. He became one of his country’s most skilled phone phreakers, a talent he used to become a fixture on computer networks all over the world. It was in fact as a network hacker rather than a programmer or game developer that he first did something to make all of Britain sit up and take notice.

On October 2, 1983, San hacked the email account of one of the presenters of a live edition of the BBC program Making the Most of the Micro, an incident that has gone down in British computing lore as the “very first live hack on TV.” Millions of Britons watched as the presenter’s computer displayed a “Hacker’s Song” from San in place of the normal login message. Like much involving San, it was both less and more than it seemed. What with War Games a huge hit in the cinema, the BBC wanted something just like what San delivered for their live show where, as the host repeatedly stated, “anything could happen.” San’s alleged victims were more like co-conspirators: “They knew I was going to hack, they were quite hoping I would,” he admits. Why else would they announce the password to all and sundry inside the studio over a live microphone just minutes before the program began? After that, it just took a phone call from a few of San’s friends who were hanging about the studio. Further circumstantial evidence of the BBC’s complicity in the whole incident is provided by the host and presenter’s weird lack of affect when the “Hacker’s Song” appeared on the screen — almost as if they expected it, or something like it, to be there. As for the “Hacker’s Song” itself, it was lifted not from some shady underground but from the very overground pages of the American magazine Newsweek, yet another gift of San’s importer/exporter father.

San was forced to cloak himself in anonymity for this great exploit, but he got the chance to advertise his skills to the world and earn himself some real money in the process soon thereafter, when he was hired by a dodgy little company called Unicom to help in the development of a new, ultra-cheap modem for the BBC Micro. He wrote the software to control the modem, much of which was supplied not on disk or tape but as a new ROM chip to be installed in the computer itself. The modem lacked approval from the British Approvals Board of Telecommunications, meaning that, in one of those circumlocutions only a hidebound bureaucracy could come up with, it was legal to buy and sell but not to actually use on the British telephone network; it was required to bear a bright red triangle on its face to indicate this. Undaunted, Unicom took the non-certification as a badge of street cred, painting little demons on either side of the BABT’s warning triangle that made it look like just part of the logo. The Unicom modem quickly became known as the “Demon Modem.” At a fraction of the price of its more legitimate competitors, it made outlaws of many thousands of Britons and earned San tens of thousands of pounds. Perhaps all those punters should have been more cautious about the people they did business with: in the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders, San makes the eye-popping claim that he imbedded backdoors into the bundled software “to take control of a computer using his modem, to make it play sounds, or type words to the screen.” This sounds frankly dubious to me given everything I know about the technology involved, but I offer it nevertheless for your consideration. At any rate, San claims he mainly used his powers to do nothing more nefarious than cheat at MUD.

San first came face to face with the executives at British Telecom not, as you might expect, because he was hauled into court for his various illegal activities, but rather when he was hired by them to help David Braben and Ian Bell port Elite from the BBC Micro to the Commodore 64. Having accomplished that task in a bare couple of months, he parlayed the success into a contract for a 3D space-combat game of his own, to target the new generation of 68000-based home computers that were on the horizon. Eager to get started, and with the Atari ST and Amiga not yet released, he rented a Macintosh for a while to start developing 3D math routines for the 68000, then shifted development to the ST as soon as it arrived in British shops. When Rainbird came into being, this 16-bit prestige project was quickly moved from Firebird to the new imprint.

The finished Starglider that was released by Rainbird in October of 1986 was once again both less and more than it seemed. With Bell and Braben having already started squabbling and proving unable or unwilling to deliver a timely follow-up to Elite, Rainbird clearly wanted to position Starglider instead as that game’s logical successor. Just as Acornsoft had for Elite, Rainbird hired an outside author, James Follett, to write a novella setting the stage for the action. Its almost 70 pages tell the story of an alien invasion force that disguise themselves as Stargliders, a protected species of spacefaring birds, in order to penetrate the automated defenses of your planet of Novenia. You play Jaysan — didn’t I say he had the perfect name for a videogame character? — who with the assistance of his hot girlfriend Katra must save his world using the last manned fighter left in its arsenal. How’s that for a young nerd’s wish-fulfillment fantasy?

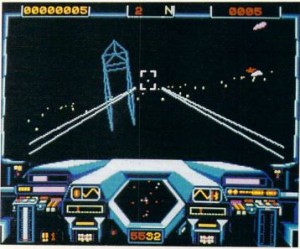

That said, connecting all of the texture provided by the novella to the actual game requires quite an effort of imagination. Starglider lacks the huge universe of Elite, and lacks with it Elite‘s strategic trading game and the slow-building sense of accomplishment that comes from improving your ship and your economic situation and climbing through the ranks. Most of all it lacks Elite‘s wondrous sense of limitless freedom. Rather than a grand space opera, Starglider is a frenetic shoot-em-up in which you down enemies for points — nothing more, nothing less. Get to and destroy a faux-Starglider, the “boss” of each level, and you advance to the next, where everything becomes a little bit harder. With no save facility beyond a high-scores table, it would fit perfectly into an arcade.

Which is not to say that Starglider wasn’t impressive in its day within its own more limited template. The game’s most innovative feature may just be its missile-eye view: when you fire a missile you can switch your view to a camera in its nose and guide it to its target yourself. There’s also a modicum of strategy required: you need to return to a depot periodically to repair your ship and restock your weapons, and you need to replenish your energy supplies by skimming over power lines located on the surface of Novenia (shades of Elite‘s fuel scoops). But mostly Starglider seems more concerned with showing off what its 3D engine can do than pushing boundaries of gameplay. Its wireframe 3D graphics aren’t exactly a revelation in comparison to Elite‘s, but there are far more enemies now with more complex shapes, which move more smoothly — the Stargliders themselves, enormous birds that smoothly flap their wings, are particularly well-done — and which are now in color.

The problem with a game that lives and dies on its technical innovations is that once those innovations are incorporated into and improved upon by other games it has very little to offer. Writing about Elite, I noted that Braben and Bell could easily have stopped after they had a workable 3D action game, the first of its kind on a PC, and been assured of having a sizable hit on their hands. What made Elite a game for the ages was their decision to keep going, to use that 3D engine as a mere building block for something grander. The lack of a similar grander vision is what makes Starglider, as reviewer Ashley Pomeroy put it, “a period piece.” Within a year or two other games would offer 3D engines that used solid polygons instead of wireframes — including, ironically, later versions of Elite itself. Many of Starglider‘s other aspects that were impressive back in the context of 1986 are most kindly described as quaint today, like the poorly digitized voice of Katra that occasionally screams out a monosyllabic exclamation. Most embarrassing of all is the brief digitized snippet of a studio-recorded theme song that plays as the game starts; it sounds like a particularly cheesy Saturday-morning toy advertisement.

The use of digitized sound from the real world is of course a signpost to the future of multimedia gaming, and represented a real coup in 1986, as San himself describes: “On the Atari ST Starglider was the first game to use sampled sound. I sat with my ST open, measuring voltages off the sound chip, and modulating the volume controls in real time on the three channels to find what voltages came out so that I could play samples.” Technically brilliant it may well be. Timeless, however, it’s not.

In its day, though, it was more than enough to make Starglider just the big hit needed to get the fledgling Rainbird imprint off the ground. Its sales soared well into the six figures once ported, with greater or lesser degrees of success, to quite a variety of 8-bit and 16-bit machines (a list that includes the Amiga and at long last the Macintosh, the platform where its development first began). The sheer number of ports illustrates what would soon become Rainbird’s standard business model: to release games first as prestige titles on the 16-bit machines, then port them down to the less capable but more numerous 8-bitters where the really big sales numbers could be found. Rainbird quickly learned that an Atari ST or Amiga game on the Commodore 64 still retained some of the cachet that clung to anything involving a 68000. (Cinemaware in the United States would quickly learn the same thing and engage in a similar triangulation.)

Jez San used the income Starglider generated to put his one-man-band days behind him, bringing in additional programmers to establish Argonaut as one of the mainstays of British game development for almost two decades to come. Argonaut became one of the leading lights of a certain school of game programming, centered in Europe, that would continue to program the new 16-bit machines largely as they had the older 8-bits: in raw assembler, banging right on the hardware and ignoring operating systems and all the rules of “proper” programming found in the manuals. The approach seemed to demand young minds. Indeed, it seemed to delight in chewing them up and spitting them out before their time. In 1987 a 21-year-old San was already starting to feel his powers fading in contrast to the young turks he was hiring to work for him; he declared he’d likely be “over the hill” in about two more years. He was therefore eager to complete the transition he’d already begun into a purely managerial role. Even professional sports didn’t worship youth like this brutal meritocracy.

San and his colleagues and the many other developers like them positively swaggered about their prowess at down-and-dirty to-the-metal assembly-language coding, treating those who chose to work differently with contempt. “I don’t believe you can write performance software in C,” said San bluntly in that same 1987 interview. What he apparently failed to understand or didn’t consider significant was that, in being forced to focus so much on the trees of registers, opcodes, and interrupts, he was forgoing a veritable forest of conceptual complexity and design innovation. Higher-level languages had, after all, been invented for a reason. It’s very difficult, even for an agile 20-year-old mind, to conceive really interesting systems and virtual worlds when one is also forced to manually keep track of the exact position of the electron gun painting the screen. Thus the games that Argonaut and houses like them produced were audiovisually spectacular in their day but can seem underwhelming in ours. The fundamental limitations of their designs are all too painfully apparent today, long after even the best of 1980s graphics and sound have lost their ability to awe. For that reason I don’t know that we’ll be hearing a lot from this school of game development in the years to come on this blog, but rest assured that they’ll be beavering away in the background, brilliant in their own ephemeral way.

(Sources: the film From Bedrooms to Billions; the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders; Amazing Computing of November 1987; Retro Gamer 86 and 98; Amiga Computing of June 1988; Your Computer of January 1985, February 1986, June 1986, October 1987; Computer and Video Games of February 1985; Popular Computing Weekly of March 21 1985, November 7 1985, November 14 1985, and March 27 1986; Computer Gamer of August 1986; Home Computing Weekly of April 30 1985; Games Machine of October 1988. The web site The Bird Sanctuary is full of information on Firebird, Rainbird, and their games. If you’d like to experience Starglider for yourself, feel free to download a zip from here containing Atari ST and Amiga disk images along with all of the goodies that accompanied them.)