Shortly after completing M.U.L.E., Ozark Softscape held a week-long brainstorming retreat with their producer from Electronic Arts, Joe Ybarra, inside the Little Rock house that served as their offices. Dan Bunten [1]Dan Bunten began living as the woman Danielle Bunten Berry in November of 1992. She died five years later.

In preparing this article, I of course reviewed what I had already written about Dani. I confess it made me cringe a bit. I have long been annoyed by the habit of people who know nothing of her games of using Dani as some generic representative of her sexuality, and wanted to move the focus firmly to her work as a game designer, to leave the politics of gender identity alone and focus on why she was a such a giant in her chosen field. I now realize that in doing so I seemed to dismiss and disrespect the other parts of her story, although I genuinely didn’t intend to do so. A couple of angry commenters who, it seemed to me, wanted to force me into the very narrative template I had been trying to avoid only hardened my position. I continue to want to avoid the standard structure of the genre of “Dani Bunten Berry stories” — but I also realize that they had some points as well. I particularly regret that I never referred to Dani by her female name even in my note at the end of the article. I literally never realized I had done this until my recent rereading, and now understand some objections about how I allegedly considered her unworthy of being referred to by her real name and the like a bit better. I won’t edit the article, as doing so could only make those who commented look unreasonable in ways they really weren’t. Anyway, it perhaps serves as a better lesson just as it is. Know, however, that if I was writing it today I would handle the issue somewhat differently.

That said, you’ve surely noticed that I continue to refer to Dani as “Dan” and “he” in the article above. I understand the logic of those who would say that Dani was always a woman, merely one who was by an accident of birth born into a man’s body. Certainly this is the argument most advocates for transsexual rights would make. For myself, I am all for transsexual rights, but also believe that gender and sexual identity may be more fluid than much transsexual rhetoric would have it. In the end, I have continued to opt for clarity and reality as all of Dani’s friends and colleagues knew it in the 1980s: of her being the man Dan Bunten. Referring to “Dani” and “she” in these articles would be confusing to the reader and at least at some level anachronistic, opposed to the consensus reality shared by everyone around her. I understand that this decision may not seem ideal to everyone, and even that it runs counter to some journalistic style guidelines. If you disagree with it, I can only ask you to believe me when I say it was made in good faith, with no intention to slight. For what it’s worth, reports are that Dani was never offended in the least by being referred to as a man when conversations came around to her years of living as Dan. arrived with a pretty good idea of the game he wanted to make next already in hand. He had recently become fascinated with a monster board game released by those famed purveyors of monster board games, Avalon Hill. Civilization places each player in charge of a single tribe at the dawn of history, about 8000 BCE, and lets her guide it down through the millennia as far as the time of the dawning of the glory that was Rome, about 230 BCE. Warfare plays a role, but Civilization isn’t really a traditional war game; equally important are exploration, culture, economics, and technological advancement. (Of course, all of these factors are inevitably interlinked.) With a scope like that, Civilization is just about as complicated and time consuming as board gaming gets. A full game generally consumes about eight hours even once you’ve learned how to play.

Dan’s colleagues dutifully set aside a day to play the game with him, to see what he was on about. They emerged blinking and befuddled, and not at all sure about the idea of a computerized version. How, after all, were they going to pack all of that complexity and grandeur into their little 48 K Atari 800s? Ybarra was likely motivated by another practical consideration: Civilization belonged to Avalon Hill, who were trying (with somewhat mixed results) to make a go of it in computer games, the place to which a dismaying quantity of their old customers were migrating. They weren’t likely to make it easy or cheap for a competitor to release a computer version of one of their big board-game titles. Better, Dan’s colleagues all argued, to make a more modest original game with some of the spirit of Civilization. This sort of conversation wasn’t that new to Ozark. Dan’s three partners, as well as Ybarra, freely acknowledged him to be a creative genius far beyond their own lights. Geniuses, however, occasionally need to be gently steered down practical roads, lest their Big Ideas overwhelm their sense of proportion; this they saw as part of their own modest contributions to Ozark.

Also in Ozark’s collection of board games was another Avalon Hill effort called Conquistador, a game of “The Age of Exploration: 1495-1600.” In it each player takes control of one of the great European powers as they explore, conquer, and eventually colonize the New World. Late in the game, wars among the players can develop as virgin territory gets harder to come by. It’s only slightly less daunting than Civilization; a complete game usually lasts five hours or so. Still, it felt like a concept that could be more readily pared down to something manageable on the Atari 800, and like one that could inspire a computer game original enough — particularly with a designer of Dan’s creativity on the project — that licensing wouldn’t become an issue. It also dealt with a subject that Dan and his brother Bill had found genuinely fascinating from an early age, when an uncle had given them their first book about the Conquistadors. And so Ozark’s next project was decided by the time the week was out.

Dan, still pining for Civilization, was initially not hugely enthusiastic. After he and Bill collected a tall stack of history books and dove in, however, he started to come around. Once again the Big Ideas started to come thick and fast. He envisioned a game played in three stages, like Conquistador. In the first, you would be exploring and dealing with the natives you encountered, which basically meant either trading and trying to establish peaceful alliances or doing a full-on Cortés and charging through their villages with swords swinging. The second stage would have you founding colonies, establishing permanent settlements and institutions in the New World rather than rushing back to Europe with each new shipful of gold. Finally, these emerging and expanding nations would have to deal with one another. Diplomacy and the results of its breakdown, wars, would ensue. Diplomacy being pretty difficult terrain for a computer opponent to navigate, Dan envisioned a game that, like M.U.L.E., would emphasize multiplayer play while offering computerized opponents merely as practice and fillers for empty human seats around the virtual table.

It was all very ambitious. Inevitably, the heartless hand of practicality — largely in the usual form of his partners — started to pare away at it pretty quickly. Stages two and three were excised entirely; this would be a game of exploration and conquest only, not politics or consolidation. You would also be restricted to playing as a representative of Spain and to exploring the lands of South and Central America that were historically conquered by Spain. The name Seven Cities of Gold was chosen as a reflection of this new emphasis on Conquistadors seeking after the wealth of exotic legends to bring home to Spain. Most painfully, it was decided to make the game single-player only, as it was ambitious enough as it was and no one knew quite how to make multiplayer work anyway. Besides, as Ybarra and everyone else at EA — not to mention the failure of M.U.L.E. — were able to attest, for whatever reason there just wasn’t a big market for multiplayer-focused strategy games. With EA and Ybarra sticking so loyally with Ozark despite M.U.L.E.‘s fate, there was perhaps a sense that Ozark owed them the best stab they could make at giving them a hit. At any rate, they owed it to themselves if they wanted to stay in this business; it was doubtful that even EA would continue to fund them if they delivered another under-performer like M.U.L.E. And so Seven Cities of Gold became the first single-player-only game Dan had ever made.

If that was a hard compromise to accept, there were consolations. The overarching Big Idea of Seven Cities, to be emphasized if necessary at the expense of everything else, would be Discovery. Dan had quickly realized when he first played Conquistador that it could not be a true recreation of the experience of exploring an uncharted continent for one very simple reason: the player came into it with a knowledge of the geography of the Americas, and with a bit of cursory outside research could know even the location of the capital of the Inca Empire. To remedy this, he proposed making a random map available in addition to the historical one. The historical map would be there out of obligation and for learning purposes; the real game would have you exploring New Worlds that were truly new to you.

The map generator turned into the most technically challenging element of the entire project. To be worthwhile, the random maps had to be as believable and logical as the historical. They couldn’t, in other words, just scatter landscape and natives about willy-nilly. From the manual:

There is a plate-tectonics model consulted for each creation. Mountain ranges are generated where the plates bump into each other. And secondary ranges (like the Allegheny Mountains on the historical map) may be created as well.

The program also consults a cultural dissemination model for its work. The influences of major civilizations are presumed to spread outward. Consequently, pueblo dwellers generally will be found between city-states and primitive agriculturalists. The model will allow for varying levels of this influence and can thus produce occasional continent arrangements which have no Incan-level civilizations. Alternately, it can make very rich and powerful arrangements, one which, like 16th-century Japan, are highly civilized from coast to coast.

The random-map generator was assigned to Jim Rushing, the purest coding mind at Ozark, who spent some four months struggling with it. It was quite a task for the little Atari; each map took a solid ten minutes of processing to generate. Frustratingly, the end result from early versions was always the same, a continent shaped like a giant peanut. Finally, Rushing found a bug in his random-number generator. Ybarra still recalls vividly the day that Dan called him to tell him that they had generated a believable alternate New World: “The energy and excitement was terrific. Dan was both elated and burnt out, but you could ‘hear’ him grinning on the other side of the phone.” Ybarra now firmly believed they were “creating another masterpiece.”

Indeed, the game is nothing if not elegant. Like in M.U.L.E., you are always embodied in the game by an onscreen avatar who visits shipyards, the pub, and the royal palace, and of course wanders through the New World as your surrogate. This can make it feel as much adventure game as strategy game; Seven Cities is anything but dry or abstract. The overland exploration which forms the heart of the game was inspired as much by Dan’s own experiences hiking the backwoods of Arkansas as his readings in history. He had particularly vivid memories of getting himself lost on occasion, and the relief engendered by coming upon a road or other familiar landmark. Seven Cities can prompt similar feelings as you press ever deep into this vast, unknown continent. The feeling of relief at finding your trusty ship sitting right there where you left it as you stumble out of the jungle with food supplies dwindling is almost indescribable.

But maybe the supreme achievement in verisimilitude is your interaction with the native tribes, as brilliant an abstraction of real-world experience into interface as the auctions of M.U.L.E. When you enter a new village, the inhabitants gather around you, surround you disconcertingly. You can give them gifts or try to “amaze” them by acting the part of one of their gods, but it’s always an uncertain, tentative communication that could erupt into violence at any time. Many times you will find yourself all but forced into massacring a village — or being massacred by them — by an inadvertent push of the joystick or a single panicked shot by a member of your own army who goes out of your control. It’s a superb simulation of how these encounters between two utterly alien cultures without a single word in common between them must have actually felt to the participants, and a lesson in just why they so often ended in violence even when both parties entered them with the best of intentions. Incredibly for a game of this vintage, the natives remember and communicate with one another. Attack one tribe in a region and the others will be much more suspicious. Try to “amaze” a group of natives too many times and it starts to become old hat — and they start to become suspicious.

For the desperately idealistic Dan, who was always eager to instil “a meaningful message,” the moral dimension of these encounters and the impact they would make on the player’s psyche were key not only to his game but to his very sense of his own worthiness as a person:

“The people I admire are the people who went to jail instead of Vietnam, or who go to India to do some good, or who are really committed to the environment. Those are the people who are really admirable. What I’m doing seems less important. I want to make a significant impact in a person’s life.”

Yet Seven Cities doesn’t preach; it leaves you to your conscience. Unquestionably, violence in Seven Cities often does pay, just as in real history, and the problematic nature of this was not lost on Dan:

“Many of the Conquistadors treated the natives horribly. Theirs was an arrogant and prideful approach to a society that had its own history and roots. But to be historically accurate required that we had to include violence. I don’t like the idea of players hurting other things, but there’s no alternative or you’re forcing your own moral decisions on an audience that ought to have a choice themselves.

“Bill and I were real Indian sympathizers when we were growing up. We always sided with the Indians instead of the cowboys. It just seems like such a neat, romantic culture to us, so in tune with the earth. Then to write a game where at least part of the game is wiping out Indians — that’s problematic.”

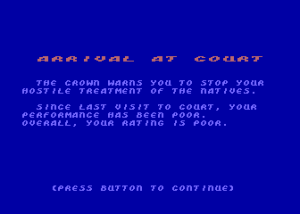

Seven Cities comments on your behavior toward the natives in only one way: if you get truly savage, the king will eventually tell you to please stop killing so many of them. But these words are never backed by any action, and the priority always remains to keep the gold flowing. The crown refuses to acknowledge that the gold and the killing that produces it are often inseparable. Such halfhearted carping is, as Dan noted, lifted straight from history, where it provided a way for those back in Spain to feel morally absolved while still benefiting from the killing and plundering of their countrymen.

Brilliant as its individual elements are, I do tend to have a problem appreciating Seven Cities of Gold as a holistic game. There is no competitor to play against, unless you count the natives you encounter — and the power imbalance between you and them is ultimately so great that, even if you choose the warlike approach, it’s hard to think of them in that role. Nor is there any in-game way to really lose or win. There isn’t even a definite end-point; you begin in 1495 and receive a rank based on your performance in 1540, but can continue to play on after that as long as you like. After a while the thrill of filling in the map and adding to my counts of missions and ships and rivers and other landmarks discovered starts to fade, and I start wishing for some goals, some sort of more specific direction. Dan himself delivered the following answer to the question, “How do I win?”

However you want. Seven Cities is a process-type game. You go along like real life. Life doesn’t have ends and wins and things like that. It has processes that you go through, and at times you stand back and say, “Hey, I’ve done pretty good so far.” Set your own goals really high and say, “That’s how I win.” Then go for it.

All of which is fine on the face of it, but Seven Cities just doesn’t feel to me like an intentional sandbox game in the mold of the (much later) SimCity. It rather feels like a design which is missing something it was originally intended to have, a possible legacy of the process of paring it down to a manageable project. On the other hand, I’m also willing to accept that this may just be down to a failure of imagination on my part, as the game received stellar reviews in its day and is still loved by many today.

Be that as it may, it seems to me that Seven Cities of Gold is still not so significant as a game in itself as for the frontiers it opened and the new things it dared to try. Its custom worlds, randomly generated at heart but meticulously terra-formed to be as believable as our own, became a staple of grand strategy games to come. Its consistent prioritizing of friendliness and elegant playability — the entire game is controlled, simply and intuitively, with a single joystick, and its manual consumes a scant 8 pages that spend as much time on historical background as game mechanics — served as an object lesson to games that used every key on the keyboard. The random maps, the native-encounter sequences, and the way that the whole game is played in “real time” rather than discrete turns also demonstrated how to take advantage of the unique abilities of the computer, rather than just encoding the rules of what could otherwise be a board game. And of course the moral ambiguity of this whole exercise, in which even peaceful alliances are ultimately made for the purpose of conquer and plunder, is never swept under the rug. Seven Cities has something to teach us about politics and history and perhaps even human nature. It goes well beyond the equipment lists and purely tactical concerns of a typical war game of the sort being pumped out by companies like SSI by the handful by 1984. Trip Hawkins declared that Ozark had pioneered a whole new genre of computer software: “edutainment.”

M.U.L.E. offered many of the same design lessons, but few others were thinking on this level at the time of Seven Cities‘s mid-1984 release. Troy Goodfellow goes so far as to call it “the most influential strategy game ever made.” That’s a bold statement even if we assume he’s implicitly restricting the field to computerized strategy games, but just the fact that Seven Cities is in the running in a world that contains games like Civilization (the computer version) says volumes.

Speaking of Civilization: one of those entranced by Seven Cities‘s innovations was a 30-year-old programmer and designer named Sid Meier, co-owner of a small publisher called MicroProse. Seven Cities and its determination to make strategy and history attractive and approachable became the inspiration for his breakthrough title, 1987’s Pirates!. The embodied interface of that game, which blurred the lines between strategy, adventure, and RPG while always making you feel that you are there, is lifted straight from Seven Cities; even the fonts and whole visual looks of the two games are similar. If Pirates!, generally acknowledged as one of the best computer games ever created, is even better than Seven Cities of Gold, it’s also true that it never could have existed without it, as Meier himself would happily admit. Later still, of course, Meier would manage what Dan never quite could, bringing all the complexity and grandeur — and then some — of the board game Civilization to the computer in an amazingly accessible way. Again, the road to Sid Meier’s Civilization could only have passed through Seven Cities of Gold.

While it may be most notable for the games it influenced, it’s also possible to say something about Seven Cities of Gold that is all too unusual in Dan Bunten’s career: the game was a hit in its own right. EA’s faith in their backwoods savants paid off at last, as Seven Cities sold at least 150,000 copies, five times the numbers done by M.U.L.E. and enough to make it EA’s biggest new game of 1984, in versions for the Atari 8-bit (the original and always the one that Dan himself saw as definitive), Commodore 64, Apple II, IBM PC, and eventually the Macintosh and the Amiga. Most of these ports were done by Ozark themselves or people within their circle. The Apple II version, for instance, came courtesy of a young University of Arkansas student named Mark Botner who spent the summer of 1984 working with them. He makes those days in the big house by the lake sound like an idyllic summer romance:

“What fun we had that summer. We would take a walk every day around Broadmoore Lake while our programs assembled for 15 minutes or so. We flew model airplanes, floated model boats in the lake, and played many different games. And, we actually got Seven Cities Of Gold ported to the Apple II!”

They were good times indeed. Suddenly the world was onto Dan Bunten and Ozark Softscape, as they (and particularly he) found themselves in constant demand for interviews, mentioned among the elites of the game industry.

While we leave our friends to enjoy a welcome taste of fame and fortune, you might want to try Seven Cities of Gold for yourself. If so, feel free to download the definitive Atari 800 version for use in the emulator of your choice.

(Finally, sources, which are largely the same as that last article: Dan wrote a column for Computer Gaming World from the July/August 1982 issue through the September/October 1985 issue. Those are a gold mine for anyone interested in understanding his design process. Particularly wonderful is his detailed history of Seven Cities of Gold‘s development in the October 1984 issue. Other interesting articles and interviews were in the June 1984 Compute!’s Gazette, the November 1984 Electronic Games, and the January 1985 Antic. Online, you’ll find a ton of historical information on World of M.U.L.E. Salon also published a good article about Dani ten years ago. The sadly now defunct Dani Bunten Berry Memorial Site is full of anecdotes and tributes, including the quote from Mark Botner which I used above. And see the site of the (apparently stalled) remake Alpha Colony for some nice — albeit somewhat buried — historical tidbits.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Dan Bunten began living as the woman Danielle Bunten Berry in November of 1992. She died five years later.

In preparing this article, I of course reviewed what I had already written about Dani. I confess it made me cringe a bit. I have long been annoyed by the habit of people who know nothing of her games of using Dani as some generic representative of her sexuality, and wanted to move the focus firmly to her work as a game designer, to leave the politics of gender identity alone and focus on why she was a such a giant in her chosen field. I now realize that in doing so I seemed to dismiss and disrespect the other parts of her story, although I genuinely didn’t intend to do so. A couple of angry commenters who, it seemed to me, wanted to force me into the very narrative template I had been trying to avoid only hardened my position. I continue to want to avoid the standard structure of the genre of “Dani Bunten Berry stories” — but I also realize that they had some points as well. I particularly regret that I never referred to Dani by her female name even in my note at the end of the article. I literally never realized I had done this until my recent rereading, and now understand some objections about how I allegedly considered her unworthy of being referred to by her real name and the like a bit better. I won’t edit the article, as doing so could only make those who commented look unreasonable in ways they really weren’t. Anyway, it perhaps serves as a better lesson just as it is. Know, however, that if I was writing it today I would handle the issue somewhat differently. That said, you’ve surely noticed that I continue to refer to Dani as “Dan” and “he” in the article above. I understand the logic of those who would say that Dani was always a woman, merely one who was by an accident of birth born into a man’s body. Certainly this is the argument most advocates for transsexual rights would make. For myself, I am all for transsexual rights, but also believe that gender and sexual identity may be more fluid than much transsexual rhetoric would have it. In the end, I have continued to opt for clarity and reality as all of Dani’s friends and colleagues knew it in the 1980s: of her being the man Dan Bunten. Referring to “Dani” and “she” in these articles would be confusing to the reader and at least at some level anachronistic, opposed to the consensus reality shared by everyone around her. I understand that this decision may not seem ideal to everyone, and even that it runs counter to some journalistic style guidelines. If you disagree with it, I can only ask you to believe me when I say it was made in good faith, with no intention to slight. For what it’s worth, reports are that Dani was never offended in the least by being referred to as a man when conversations came around to her years of living as Dan. |

|---|