“Mummy, what’s a group of lemmings called?”

“A pact. That’s right, a suicide pact.”

“Mummy, when a lemming dies does it go to heaven like all good little girls?”

“Don’t be soft. They burn in hell — like distress flares.”

(courtesy of the January 1991 issue of The One)

If you had looked at the state of Psygnosis in 1990 and tried to decide which of their outside developers would break the mold of beautiful-but-empty action games, you would have no reason to single out DMA Design over any of the others. Certainly Menace and Blood Money, the two games DMA had already created for Psygnosis, gave little sign that any visionaries lurked within their ranks. From their generic teenage-cool titles to their rote gameplay, both games were as typical of Psygnosis as anything else in their catalog.

And yet DMA Design — and particularly their leader, David Jones — did in fact have abilities as yet undreamt of. People have a way of surprising you sometimes. And isn’t that a wonderful thing?

There are some interesting parallels between the early days of DMA Design and the early days of Imagine Software, that predecessor to Psygnosis. Like Imagine, DMA was born in a city far from the cultural capitals of Britain — even farther away than Liverpool, in fact, all the way up in Dundee, Scotland.

Dundee as well had traditionally been a working-class town that thrived as a seaport, until the increasing size of merchant ships gradually made the role untenable over the course of the twentieth century. Leaders in Dundee, as in Liverpool, worked earnestly to find new foundations for their city’s economy. And one of these vectors of economic possibility — yet again as in Liverpool — was electronics. Dundee convinced the American company National Cash Register Corporation, better known as NCR, to build their principal manufacturing plant for Britain and much of Europe there as early as 1945, and by the 1960s the city was known throughout Britain as a hub of electronics manufacture. Among the electronics companies that came to Dundee was Timex, the Norwegian/Dutch/American watchmaking conglomerate.

In 1980, Sinclair Research subcontracted out most of the manufacture of their new ZX80 home computer to the Timex plant in Dundee. The relationship continued with the ZX81, and then with Sinclair’s real heavy hitter, the Spectrum. By 1983, Timex was straining to keep up with demand for the little machines, hiring like mad in and around Dundee in order to keep the production lines rolling day and night.

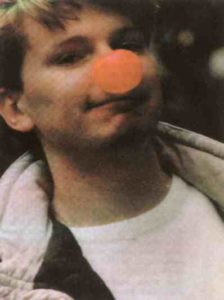

David Jones. (It’s my understanding that the nose is removable.)

One of the people they hired was David Jones, 18 years old and fresh out of an experimental new “computer studies” program that was being pioneered in Dundee. He came to Timex on an apprenticeship, which paid for him to take more computer courses at nearby Kingsway Technical College.

Just as had Bruce Everiss’s Microdigital shop in Liverpool, Kingsway College was fomenting a hacking scene in Dundee, made up largely of working-class youths who but for this golden chance might have had to resign themselves to lives spent sweeping out warehouses. Both students of the college and interested non-students would meet regularly in the common areas to talk shop and, inevitably, to trade pirated games. Jones became one of the informal leaders of the collective. To ensure a steady supply of games for his mates, he even joined a cracking group in the international piracy “scene” who called themselves the Kent Team.

But for the most dedicated of the Kingsway gang, Jones among them, trading and playing games was a diversion rather than the real point. Like the gang as a whole, this hacker hardcore was of disparate temperaments and ages — one of them, named Mike Dailly, was just 14 years old when he started showing up at the college — but they were united by a certain seriousness about computers, by the fact that computers for them were, rather than just a hobby or even a potential means of making a living, an all-consuming passion. Unlike their more dilettantish peers, they were more interested in understanding how the games they copied worked and learning how to make their own than they were in playing them for their own sake.

In 1986, Sinclair sold their entire extant home-computer line to Amstrad, who promptly took the manufacturing of same in-house, leaving Timex out of a huge contract. Most of the Dundee plant’s employees, Jones among them, were laid off as a result. At the urging of his parents, he invested half of his £2000 severance check into a degree course in Computer Science at the Dundee College of Technology (now known as Abertay University). He used the other half to buy a Commodore Amiga.

Brand-new and pricey, the Amiga was still a very exotic piece of kit anywhere in Britain in 1986, much less in far-flung Dundee; Jones may very well have been the first person in his hometown to own one. His new computer made him more popular than ever among the Kingsway hackers. With the help of his best buddies from there and some others he’d met through the Kent Team, his experiments with his new toy gradually coalesced around making a shoot-em-up game that he could hopefully sell to a publisher.

David Jones first met Ian Hetherington and Dave Lawson of Psygnosis in late 1987, when he took his shoot-em-up-in-progress to a Personal Computer World Show to hawk it to potential publishers. Still at that age when the events of last year, much less those of three years ago, seem like ancient history, he had little awareness of their company’s checkered past as Imagine, and less concern about it. “You know, I don’t think I even researched it that well,” he says. “I remember the stories about it, but back in those days everything was moving so quickly, it never even crossed my mind.” Instead he was wowed, like so many developers, by Psygnosis’s cool good looks. The idea of seeing his game gussied up by the likes of Roger Dean was a difficult one to resist. He also liked the fact that Psygnosis was, relatively speaking, close to Dundee: only about half a day by car.

Menace

Psygnosis was perhaps slightly less impressed. They agreed to publish the game, running it through their legendary art department in the process, giving it the requisite Roger Dean cover, and changing the name from the Psygnosis-like Draconia to the still more Psygnosis-like Menace. But they didn’t quite judge it to be up to the standard of their flagship games, publishing it in a smaller box under a new budget line they were starting called Psyclapse (a name shared with the proposed but never-completed second megagame from the Imagine days).

Still, even at a budget price and thus a budget royalty rate, Menace did well enough to make Jones a very happy young man, selling about 20,000 copies in the still emerging European Amiga market. It even got a showcase spot in the United States, when the popular television program Computer Chronicles devoted a rare episode to the Amiga and Commodore’s representative chose Menace as the game to show off alongside Interplay’s hit Battle Chess; host Stewart Cheifet was wowed by the “really hot graphics.” A huge auto buff — another trait he shared with the benighted original founders of Imagine — Jones made enough from the game to buy his first new car. It was a Vauxhall Astra hot hatch rather than a Ferrari, but, hey, you had to start somewhere.

Even before Menace‘s release, he had taken to calling his informal game-development club DMA Design, a name that fit right in with Psygnosis’s effect-obsessed aesthetic: “DMA” in the computer world is short for “Direct Memory Access,” something the Amiga’s custom chips all utilized to generate audiovisual effects without burdening the CPU. (When the glory days of Psygnosis with Amiga tech-heads had passed, Jones would take to saying that the name stood for “Doesn’t Mean Anything.”) In the wake of Menace‘s success, he decided to drop out of college and hang up his shingle in a cramped two-room space owned by his fiancée’s father, located on a quiet street above a baby shop and across the way from a fish-and-chips joint. He moved in in August of 1989, bringing with him many of his old Kingsway College mates on a full-time or part-time basis, as their circumstances and his little company’s income stream dictated.

DMA’s first office, a nondescript place perched above a baby shop in Dundee. That’s artist Gary Timmons peering out the window. It was in this improbable location that the most successful game the British games industry had produced to date was born.

DMA, which still had more the atmosphere of a computer clubhouse than a conventional company, gladly took on whatever projects Psygnosis threw them, including the rather thankless task of converting existing Amiga titles — among them Shadow of the Beast — to more limited, non-Amiga platforms like the Commodore 64. Meanwhile Jones shepherded to completion their second original game, another typically Psygnosisian confection called Blood Money. This game came out as a full-price title, a sign that they were working their way up through the ranks. Even better, it sold twice as many copies as had Menace.

So, they charged ahead on yet another game cut from the same cloth. Just about everything you need to know about their plans for Gore is contained in the name. Should you insist on more information, consider this sample from a magazine preview of the work-in-progress: “Slicing an adversary’s neck in two doesn’t necessarily guarantee its defeat. There’s a chance the decapitated head will sprout wings and fly right back at you!” But then, in the midst of work on that charming creation, fate intervened to change everything forever for DMA and Psygnosis alike.

The process that would lead to the most popular computer game the nation of Britain had yet produced had actually begun months before, in fact within days of the DMA crew moving into their new clubhouse. It all began with an argument.

Blood Money was in the final stages of development at the time — it would be released before the end of 1989 — and, having not yet settled on making Gore, Jones and company had been toying with ideas for a potential sequel they tentatively called Walker, based around one of the characters in Blood Money, a war robot obviously inspired by the Imperial walkers in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. Scott Johnson, an artist whom DMA had recently rescued from a life of servitude behind the counter of the local McDonald’s, said that the little men which the walker in the new game would shoot with its laser gun and crush beneath its feet would need to be at least 16 by 16 pixels in size to look decent. Mike Dailly, the Kingsway club veteran, disagreed, and set about trying to prove himself right by drawing them inside a box of just 8 by 8 pixels.

But once he got started drawing little men in Deluxe Paint, he just couldn’t stop. (Deluxe Paint did always tend to have that effect on people; not for nothing did artist George Christensen once call it “the greatest videogame ever designed.”) Just for fun, he added a ten-ton weight out of a Coyote-and-Road-Runner cartoon, which crushed the little fellows as they walked beneath it. Johnson soon jumped back into the fray as well, and the two wound up creating a screen-full of animations, mostly showing the little characters coming to various unhappy ends. Almost forgotten by the end of the day was the fact that Dailly had proved his point: a size of 8 by 8 pixels was enough.

This screen of Deluxe Paint animations, thrown together on a lark one afternoon by a couple of bored young men, would spawn a franchise which sold 15 million games.

It was another member of the DMA club, Russell Kay, who looked at the animations and spoke the fateful words: “There’s a game in that!” He took to calling the little men lemmings. It was something about the way they always seemed to be moving in lockstep and in great quantities across the screen whenever they showed up — and the way they were always blundering into whatever forms of imaginative deaths their illustrators could conjure up. The new name resulted in the appearance of the little men morphing into something not quite rodent-like but not quite human either, a bunch of vaguely Smurf-like fellows with bulbous noses and a cuteness people all over the world would soon find irresistible — even as they watched them die horribly by the dozens.

The very first lemmings

Did you know?

James Bond author Ian Fleming’s real name was in fact Ian Frank Lemming. It doesn’t take a genius to see how easily a mistake was made.

Success for Jane Lemming was always on the cards, but it took a change of name and hairstyle to become a top television personality — better known as Jan Leeming.

“One day you’ll be a big movie star,” someone once told leading Hollywood heartthrob Jack Lemmon (real name Jack Lemming). And he is.

(courtesy of the January 1991 issue of The One)

The actuality of real-world lemmings is in fact very different from the myth of little rodent soldiers following one another blindly off the side of a cliff. The myth, which may first have shown up in print in Cyril Kornbluth’s 1951 science-fiction story “The Marching Morons,” was popularized by Disney later in the decade, first in their cartoons and later in a purported nature documentary called White Wilderness, whose makers herded the poor creatures off a cliff while the cameras rolled.

While it has little to no basis in reality, the myth can be a difficult proposition to resist in terms of metaphor. Fans of Infocom’s interactive fiction may remember lemmings showing up in Trinity, where the parallel between lemmings marching off a cliff and Cold War nuclear brinkmanship becomes a part of author Brian Moriarty’s rich symbolic language. It’s safe to say, though, that no similarly rarefied thoughts about the creatures were swirling around DMA Design. They just thought they were really, really funny.

Despite Russell Kay’s prophetic comment, no one at DMA Design was initially in a hurry to do anything more with their lemmings than amuse themselves. For some months, the lemmings were merely a joke that was passed around DMA’s circle in Dundee in the form of pictures and animations, showing them doing various ridiculous things and getting killed in various hilarious ways.

In time, though, Jones found himself at something of an impasse with the Gore project. He had decided he simply couldn’t show all the gore he wanted to on a 512 K Amiga, but Psygnosis was extremely reluctant, despite the example of other recent releases like Dungeon Master, to let him make a game that required 1 MB of memory. He decided to shelve Gore for a while, to let the market catch up to his ambitions for it. In the meantime, he turned, almost reluctantly, to those lemmings that were still crawling all over the office, to see if there was indeed a game there. The answer, of course, would prove to be a resounding yes. There was one hell of a game there, one great enough to ensure that Gore would never cross anyone’s mind again.

The game which Jones started to program in June of 1990 was in one sense a natural evolution of the animations, so often featuring long lines of marching lemmings, that his colleagues had been creating in recent months. In another, though, it was a dramatic break from anything DMA — or, for that matter, Psygnosis — had done before, evolving into a constructive puzzle game rather than another destructive action game.

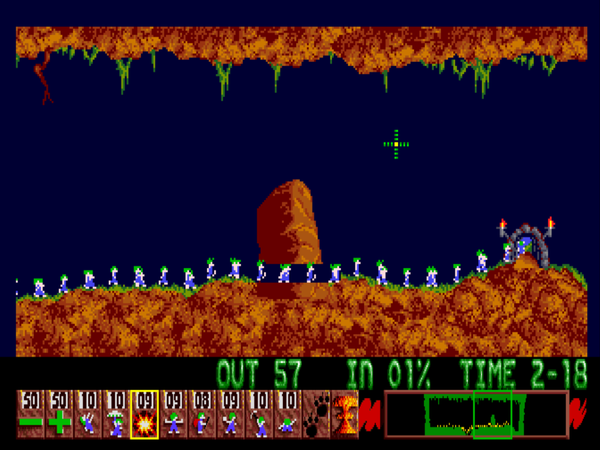

That said, reflexes and timing and even a certain amount of destruction certainly have their roles to play as well. Lemmings is a level-based game. The little fellows — up to 100 of them in all — pour out of a chute and march mindlessly across the level’s terrain from left to right. They’ll happily walk off cliffs or into vats of water or acid, or straight into whatever other traps the level contains. They’ll turn around and march in the other direction only if they encounter a wall or other solid barrier — and, once they start going from right to left instead of left to right, they won’t stop until they’re dead or they’re forced to turn around yet again. Your task is to alter their behavior just enough to get as many of them as possible safely to the level’s exit. Doing so often requires sacrificing some of them for the greater good.

To meet your goal, you have a limited but surprisingly flexible palette of possibilities at your disposal. You can change the behavior of individual lemmings by assigning them one or both of two special abilities, and/or by telling them to perform one of six special actions. The special abilities include making a lemming a “climber,” able to crawl up sheer vertical surfaces like a sort of inchworm; and making a lemming a “floater,” equipped with an umbrella-cum-parachute which will let him fall any distance without harm. The special actions include telling a lemming to blow himself up (!), possibly damaging the terrain around him in the process; turning him into a “blocker,” standing in one place and forcing any other lemmings who bump into him to turn around and march in the other direction; having him build a section of bridge — or, perhaps better said, of an upward-angling ramp; or having him dig in any of three directions: horizontally, diagonally, or vertically. Each level lets you use each special ability and each special action only a limited number of times. These restrictions are key to much of the challenge of the later levels; advanced Lemmings players become all too familiar with the frustration of winding up short by that one bridge-builder or digger, and having to start over with a completely new approach because of it.

In addition to the tools at your disposal which apply to individual lemmings, you also have a couple of more universal tools to hand. You can control the rate at which lemmings pour out of the entrance chute — although you can’t slow them down below a level’s starting speed — and you can pause the game to take a breather and position your cursor just right. The later levels require you to take advantage of both of these abilities, not least because each level has a time limit.

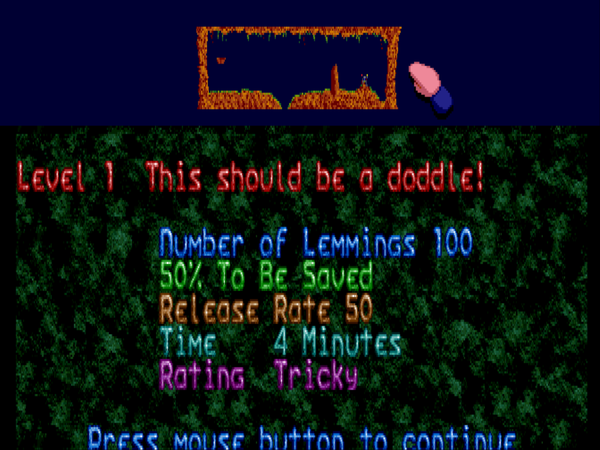

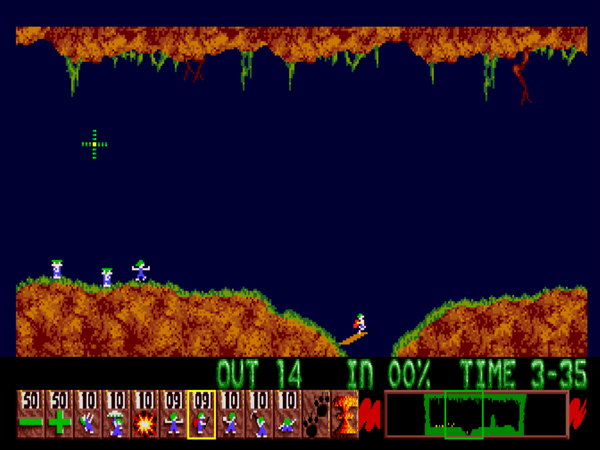

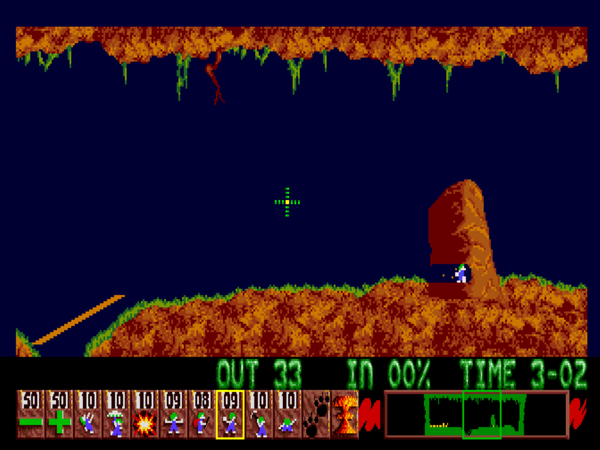

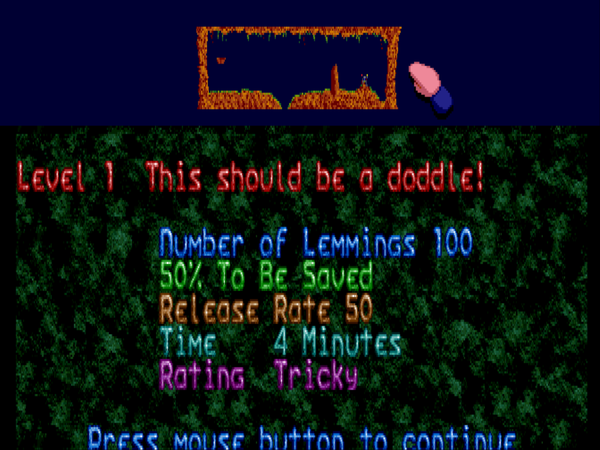

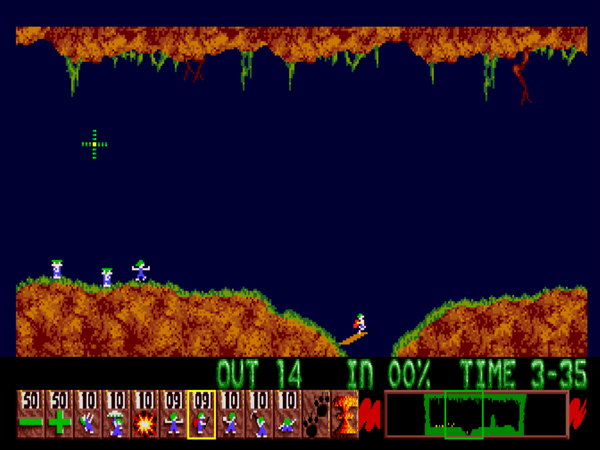

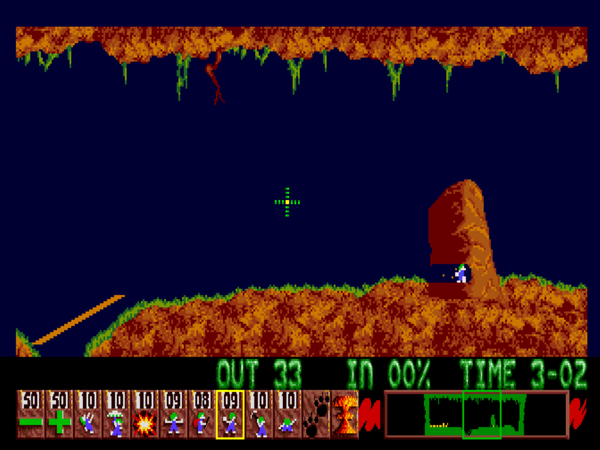

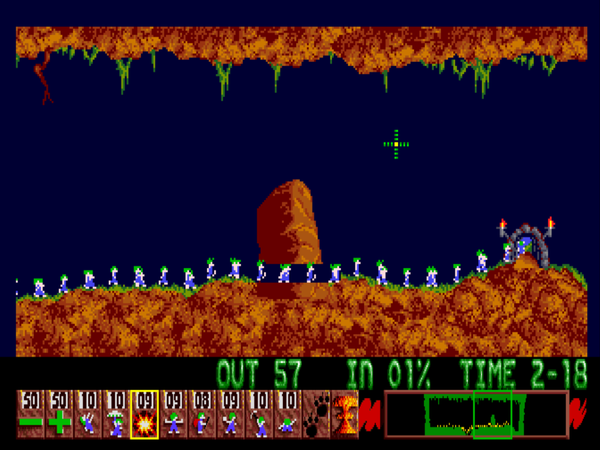

A Four-Screenshot Introduction to Lemmings

We’re about to begin one of the early levels — the first on the second difficulty level, or 31st out of 120 in all. We see the level’s name, the number of lemmings with which we have to deal, the number we’re required to save, their “release rate” — how quickly they fall out of the chute and into the world — and how much time we have.

Now we’ve started the level proper. We need to build a bridge to cross this gap. To keep the other lemmings from rushing after our slow-working bridge-builder and falling into the abyss, we’ve turned the one just behind him into a blocker. When we’re ready to let the lemmings all march onward, we can tell the blocker to blow himself up, thus clearing the way again. Note our toolbar at the bottom of the screen, including the count of how many of each type of action we have left.

With the gap safely bridged, we turn our lead lemming into a horizontal digger — or “basher” in the game’s preferred nomenclature — to get through the outcropping.

There were no other barriers between our lead lemming and the exit. So, we’ve blown up our blocker to release the hounds — er, lemmings — and now watch them stream toward the exit. We’ve only lost one lemming in total, that one being our poor blocker — a 99-percent survival rate on a level that only required us to save 50 percent. But don’t get too cocky; the levels will soon start getting much, much harder.

Setting aside design considerations for the moment, Lemmings is nothing short of an amazing feat in purely technical terms. Its levels, which usually sprawl over the width of several screens, consist entirely of deformable terrain. In other words, you can, assuming you have the actions at your disposal, dig wherever you want, build bridges wherever you want, etc., and the lemmings will interact with the changed terrain just as you would expect. To have the computer not just paint a landscape onto the screen but to be aware of and reactive to the potentially changing contents of every single pixel was remarkable in the game’s day. And then to move up to 100 independent lemmings in real time, while also being responsive to the player’s inputs… Lemmings is a program any hacker would be thrilled to claim.

As soon as he had the basic engine up and running, David Jones visited Psygnosis with it and “four or eight” levels in tow, to show them what he was now planning to turn into DMA’s next game. Jones:

They were a big company, probably about thirty or forty people. I said, “I’ll just go out to lunch, but what I’ll do is I’ll just leave the demo with a bunch of you here — grab it, play it, see what you think.” I remember coming back from lunch and it was on every single machine in the office. And everybody was just really, really enjoying it. At that time I thought, “Well, we have something really special here.”

That reaction would become typical. In an earlier article, I wrote about a Tetris Effect, meant to describe the way that game took over lives and destroyed productivity wherever it went. We might just as well coin the term “Lemmings Effect” now to describe a similar phenomenon. Part and parcel of the Lemmings Effect were all the terrible jokes: “What do lemmings drink?” “Lemmingade!” “What’s their favorite dessert?” “Lemming meringue pie!”

Following its release, Lemmings would be widely greeted as an immaculate creation, a stroke of genius with no antecedents. Our old friend Bruce Everiss, not someone inclined to praise anything Ian Hetherington was involved in without ample justification, nevertheless expressed the sentiment in his inimitably hyperbolic way in 1995:

In the worlds of novels and cinema, it is recognised that there are only a small number of plots in the universe. Each new book or film takes one of these plots and interprets it in a different way.

So it is in computer games. Every new title has been seen in many different guises; it is merely the execution that is new. The Amiga unleashed new levels of sound, graphics, and computer power on the home market. Software titles utilised these capabilities in some amazing packages, but they were all just re-formulations of what had gone before.

Until Lemmings. DMA Design created a totally new concept. In computer games this is less common than rocking-horse manure. Not only was the concept of Lemmings completely new, but also the execution was exemplary, displaying the Amiga’s capabilities well.

Lemmings is indeed a shockingly original game, made all the more shocking by coming from a developer and a publisher that had heretofore given one so little reason to anticipate originality. Still, if we join some of the lemmings in digging a bit beneath the surface, we can in fact see a source for some of the ideas that went into it.

David Jones and his colleagues were fanatic devotees of Peter Molyneux’s Populous before and during their work on Lemmings. Populous, like Lemmings, demands that you control a diffuse mass of actors through somewhat indirect means, by manipulating the environment and changing the behavior of certain individuals in the mass. Indeed, Lemmings has a surprising amount in common with Populous, even as the former is a puzzle game of rodent rescue and the latter a strategy game of Medieval warfare. Jones and company went so far as to add a two-player mode to Lemmings in homage to the Populous tournaments that filled many an evening spent in the clubhouse above the baby shop. (In the case of Lemmings, however, the two-player mode wouldn’t prove terribly popular, not least because it required a single Amiga equipped with two mice; unique and entertaining, it’s also largely forgotten today, having been left out of the sequels and most of the ports.)

Although it’s seldom if ever described using the name, Lemmings thus fits into a group of so-called “god games” that were coming to the fore at the turn of the decade; in addition to Populous, the other famous exemplar from the time is Will Wright’s SimCity. More broadly, it also fits into a longstanding British tradition of spatial puzzle games, as exemplified by titles like The Sentinel.

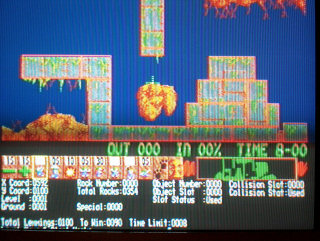

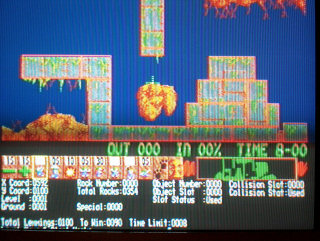

The Lemmings level editor

But one area where David Jones and company wisely departed from the model of Populous and The Sentinel was in building all of the levels in Lemmings by hand. British programmers had always had a huge fondness for procedural generation, which suited both the more limited hardware they had to work with in comparison to their American peers and the smaller teams in which they generally worked. Jones bucked that precedent by building a level editor for Lemmings as soon as he had the game engine itself working reasonably well. The gang in and around the clubhouse all spent time with the level editor, coming up with devious creations. Once a week or so, they would vote on the best of them, then upload these to Psygnosis.

Belying their reputation for favoring style over substance, Psygnosis had fallen in love with the game of Lemmings from the day of Jones’s first visit with his early demo in tow. It had won over virtually everyone who worked there, gamer and non-gamer alike. That fact became a key advantage for the work-in-progress. Everyone in Liverpool would pile on to play the latest levels as they were sent over from Dundee, faxing back feedback on which ones should make the cut and how those that did could be made even more interesting. As the game accelerated toward completion, Jones started offering a £10 bounty for every level that passed muster with Psygnosis, leading to yet more frenzied activity in both Dundee and Liverpool. Almost accidentally, DMA and Psygnosis had hit upon a way of ensuring that Lemmings would get many times the play-testing of the typical game of its era, all born of the fact that everyone was dying to play it — and dying to talk about playing it, dying to explain how the levels could be made even better. The results would show in the finished product. Without the 120 lovingly handcrafted levels that shipped with the finished game, Lemmings would have been an incredible programming feat and perhaps an enjoyable diversion, but it could never have been the sensation it became.

Just as the quality of the levels was undoubtedly increased immeasurably by the huge willing testing pool of Psygnosis staffers, their diversity was increased by having so many different personalities making them. Even today, those who were involved in making the game can immediately recognize a level’s author from its design and even from its graphical look. Gary Timmons, a DMA artist, became famed, oddly enough given his day job, for his minimalist levels that featured little but the bare essentials needed to fulfill their functions. Mike Dailly, at the other extreme, loved to make his levels look “pretty,” filling them with colors and patterns that had nothing to do with the gameplay. The quintessential examples of Dailly’s aesthetic were a few special levels which were filled with graphics from the earlier Psygnosis games Shadow of the Beast I and II, Awesome, and DMA’s own Menace.

Awesome meets Lemmings. For some reason, I find the image of all these little primary-colored cartoon lemmings blundering through these menacing teenage-cool landscapes to be about the funniest — and certainly the most subversive — thing in the entire game.

But of course the most important thing is how the levels play — and here Lemmings only rarely disappoints. There are levels which play like action games, demanding perfect clicking and good reflexes above all; there are levels which play like the most cerebral of strategy games, demanding perfect planning followed by methodical execution of the plan. There are levels where you need to shepherd a bare handful of lemmings through an obstacle course of tricks and traps without losing a single one; there are levels where you have 100 lemmings, and will need to kill 90 percent of them in order to get a few traumatized survivors to the exit. There are levels which are brutally compressed, where you have only one minute to succeed or fail; there are levels which you give you fully nine minutes to guide your charges on a long journey across several screens worth of terrain.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Lemmings is the way it takes the time to teach you how to play it. The very first level is called “Just Dig!,” and, indeed, requires nothing more of you. As you continue through the first dozen levels or so, the game gradually introduces you to each of the verbs at your command. Throughout the levels that follow, necessity — that ultimate motivator — will force you to build upon what you already know, learning new tricks and new combinations. But it all begins gently, and the progression from rank beginner to master lemming-herder feels organic. Although the general trajectory of the difficulty is ever upward as you work your way through the levels, there are peaks and valleys along the way, such that a level that you have to struggle with for an hour or two will usually be followed by one or two less daunting challenges.

All of this has since become widely accepted as good design practice, but games in 1990 were very seldom designed like this. Looking for contemporaneous points of comparison, the best I can come up with is a game in a very different genre: the pioneering real-time dungeon-crawler Dungeon Master, which also gently teaches you how to play it interactively, without ever resorting to words, and then slowly ramps up the difficulty until it becomes very difficult indeed. Dungeon Master and Lemmings stand out in gaming history for not only inventing whole new paradigms of play, but for perfecting them in the same fell swoop. Just as it’s difficult to find a real-time dungeon crawler that’s better than Dungeon Master, you won’t find a creature-herding puzzle game that’s better than the original Lemmings without looking long and hard.

If I was to criticize anything in Lemmings, I’d have to point to the last handful of levels. For all its progressive design sensibilities, Lemmings was created in an era when games were expected to be hard, when the consensus view had it that actually beating one ought to be a monumental achievement. In that spirit, DMA pushed the engine — not to mention the player — to the ragged edge and perhaps a little beyond in the final levels. A blogger named Nadia, who took upon herself the daunting task of completing every single level in every single Lemmings game and writing about them all, described the things you need to do to beat many of these final levels as “exploiting weird junk in the game engine.” These levels are “the wrong kind of difficult,” she goes on to say, and I agree. Ah, well… at least the very last level is a solid one that manages to encompass much of what has come before, sending the game out on a fine note.

Here we see one of the problems that dog the final levels. There are 49 lemmings packed together in a tiny space. I have exactly one horizontal dig at my disposal, and need to apply it to a lemming pointing to the right so the group can make its exit, but there’s no possible way to separate one lemming from another in this jumble. So, I’m down to blind luck. If luck isn’t with me — if the lemming I wind up clicking on is pointed in the wrong direction — I have to start the level over through no fault of my own. It will then take considerable time and effort to arrive back at this point and try again. This sort of situation is sometimes called “fake difficulty” — difficulty that arises from the technical limitations of the interface or the game engine rather than purer design considerations. It is, needless to say, not ideal.

To modern ears, taking this ludic masterpiece from nothing to finished in less than a year sounds like an incredible feat. Yet that was actually a fairly long development cycle by the standards of the British games industry of 1990. Certainly Psygnosis’s marketers weren’t entirely happy about its length. Knowing they had something special on their hands, they would have preferred to release it in time for Christmas. Thankfully, better sense prevailed, keeping the game off the market until it was completely ready.

As Lemmings‘s February 1991 release date approached, Psygnosis’s marketers therefore had to content themselves with beating the hype drum for all it was worth. They sent early versions to the magazines, to enlist them in building up the buzz about the game. One by one, the magazines too fell under the thrall of the Lemmings Effect. Amiga Format would later admit that they had greeted the arrival of the first jiffy bag from Psygnosis with little excitement. “Some snubbed it at first,” they wrote, “saying that they didn’t like puzzlers, but in the end the sound of one ‘Oh, no!’ would turn even the most hardened cynic into an addict.”

When a journalist from the American magazine .info visited Liverpool, he went to a meeting where Psygnosis showed the game to their distributors for the first time. The reaction of these jaded veterans of the industry was as telling as had been the Lemmings Effect that had swept through all those disparate magazine offices. “They had to be physically torn away from the computers,” wrote .info, “and crowds of kibitzers gathered to tell the person playing how to do it.” When an eight-level demo version of the game went out on magazine cover disks a few weeks before the launch, the response from the public at large was once again in David Jones’s words “tremendous,” prompting the usually cautious Psygnosis — the lessons of the Imagine days still counted with Ian Hetherington — to commit to an initial pressing that was far larger than they had done for any game before.

And yet it wasn’t anywhere near large enough. When Lemmings was released on Valentine’s Day, 1991, its first-day sales were unprecedented for Psygnosis, who were, for all their carefully cultivated cool, still a small publisher in a big industry. Jones remembers Ian Hetherington phoning him up hourly to report the latest numbers from the distributors: 40,000 sold, 50,000 sold. On its very first day, the game sold out all 60,000 copies Psygnosis had pressed. To put this number in perspective, consider that DMA’s Menace had sold 20,000 copies in all, Blood Money had sold 40,000 copies, and a game which sold 60,000 copies over its lifetime on the Amiga was a huge success by Psygnosis’s usual standards. Lemmings was a success on another level entirely, transforming the lives literally overnight of everyone who had been involved in making it happen. Psygnosis would struggle for months to turn out enough copies to meet the insatiable demand.

Unleashed at last to write about the game which had taken over their offices, the gaming press fell over themselves to praise it; it may have been only February, but there was no doubt what title was destined to be game of the year. The magazine The One felt they needed five pages just to properly cover all its nuances — or, rather, to gush all over them. (“There’s only one problem with Lemmings: it’s too addictive by half. Don’t play it if you have better things to do. You won’t ever get round to doing them.”) ACE openly expressed the shock many were feeling: shock that this hugely playable game could have come out of Psygnosis. It felt as if all of the thinking about design that they could never be bothered to do in the past had now been packed into this one release.

And as went the British Amiga scene, so went Europe and then the world. The game reached American shores within weeks, and was embraced by the much smaller Amiga scene there with the same enthusiasm their European peers had evinced. North American Amiga owners had seen their favored platform, so recently the premiere gaming computer on their continent as it still was in Europe, falling out of favor over the course of the previous year, with cutting-edge releases like Wing Commander appearing first on MS-DOS and only later making their way — and in less impressive versions at that — to the Amiga. Lemmings would go down in history as a somewhat melancholy milestone: as one of the last Amiga games to make American owners of other computers envious.

But then, Psygnosis had no intention of keeping a hit like this one as an Amiga exclusive for very long. Within months, an MS-DOS version was available. Amiga owners didn’t hesitate to point out its failings in comparison to the original — the controls weren’t quite right, they insisted, and the unique two-player mode had been cut out entirely — but the game’s charms were still more than intact enough. It was in MS-DOS form that Lemmings really conquered North America, thus belatedly fulfilling for Ian Hetherington, last man standing at Psygnosis from the Imagine days, the old Imagine dream of becoming a major player on the worldwide software stage. In 1992, the magnitude of their newfound success in North America led Psygnosis to open their first branch office in Boston. The people who worked there spent most of their time answering a hint line set up for the hundreds of thousands — soon, millions, especially after the game made its way to Nintendo consoles — of frazzled Americans who were hopelessly stymied by this or that level.

Britain was the country that came the closest to realizing the oft-repeated ambition of having its game developers treated like rock stars. DMA Design was well-nigh worshiped by Amiga owners in the wake of Lemmings. Here they appear in a poster inserted into a games magazine, ready to be pasted onto a teenage girl’s wall alongside her favorite boy bands. Well, perhaps a really nerdy teenage girl’s wall. Hey, it could happen…

There was talk for some time of polishing up David Jones’s in-house level editor and turning it into a Lemmings Construction Kit, but Psygnosis soon decided that they would rather sell their customers more content in the form of add-on disks than a way of making their own levels. Addicts looking for their next fix could thus get their hands on Oh, No! More Lemmings before the end of 1991, with 100 more levels on offer. This collection had largely been assembled from the cast-offs that hadn’t quite made the cut for the first game, and the reasons why weren’t that hard to sense: these levels were hard, and a little too often in that same cheap way as some of the final levels from the original. Still, it served the purpose, delivering another huge hit. That Christmas, Psygnosis gave away Xmas Lemmings, a free demo disk with a few levels re-skinned for the holiday season. They hit upon a magical synergy in doing so; the goofy little creatures, now dressed in Santa suits, went together perfectly with Christmas, and similar disks would become a tradition for several more holiday seasons to come.

This insertion of Lemmings into the cozy family atmosphere of Christmas is emblematic of the game’s appeal to so many outside the usual hardcore-gamer demographic. Indeed, Lemmings joined Tetris during this period in presaging the post-millennial casual-game market. Perhaps even more so than Tetris, it has most of the important casual traits: it’s eminently approachable, easy to learn, bright and friendly in appearance, and thoroughly cute. Granted, it’s cute in an odd way that doesn’t reward close thinking overmuch: the lemmings are after all exploding when they pipe up with their trademark “Oh, no!,” and playing the game for any length of time entails sending thousands upon thousands of the little buggers to their deaths. And yet cute it somehow manages to be.

One important quality Lemmings shares with Tetris is the way it rewards whatever level of engagement you care to give it. The early levels can be blundered through by anyone looking for a few minutes’ diversion — stories abounded of four-year-olds managing the training levels — but the later ones will challenge absolutely anyone who tackles them. Likewise, the level-based structure means Lemmings can be used to fill a coffee break or a long weekend, as you wish. This willingness to meet players on their own terms is another of the traits of gaming’s so-called “casual revolution” to come. It’s up to you to get off the train wherever interest and dedication dictate.

But those aspects of the Lemmings story — and with them the game’s full historical importance — would be clearly seen only years in the future. In the here and now, DMA had more practical concerns. David Jones abandoned the clubhouse above the baby shop for much larger digs, hired more staff, and went back to the grindstone to deliver a full-fledged sequel. He didn’t, however, neglect to upgrade his lifestyle to match his new circumstances, including the requisite exotic sports car.

Unlike the old guard of Imagine Software, Jones could actually afford his excesses. When all the sales of all the sequels that would eventually be released are combined with those of the original, the total adds up to some 15 million games sold, making Lemmings by far the biggest gaming property ever to be born on the Amiga and the biggest to be born in Britain prior to Grand Theft Auto — a series which, because the success of Lemmings apparently hadn’t been enough for them, the nucleus of DMA Design would later be responsible for as well.

Meanwhile Psygnosis, now The House That Lemmings Built, also found larger offices, in Liverpool’s Brunswick Business Park, and began to cautiously indulge in a bit more excess of their own. Ian Hetherington was the only Imagine veteran still standing, but never mind: games on the Mersey had finally come of age thanks to a game from — of all places! — Dundee.

(Sources: the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Videogames Conquered the World by Rebecca Levene and Magnus Anderson and Sinclair and the “Sunrise” Technology: The Deconstruction of a Myth by Ian Adamson and Richard Kennedy; the 1989 episode of Computer Chronicles entitled “The Commodore Amiga”; The One of June 1989, March 1990, September 1990, and January 1991; .info of November 1990 and February 1991; Amiga Format of May 1993 and July 1995, and the annual for 1992; The Games Machine of June 1989; ACE of April 1991; Amiga World of June 1991; Amazing Computing of April 1991 and March 1992; the online articles “From Lemmings to Wipeout: How Ian Hetherington Incubated Gaming Success” from Polygon, “The Psygnosis Story: John White, Director of Software” from Edge Online, and “An Ode to the Owl: The Inside Story of Psygnosis” from Push Square; “Playing Catch Up: GTA/Lemmings‘ Dave Jones” from Game Developer; Mike Dailly’s “Complete History of DMA Design.” My thanks also go to Jason Scott for sharing his memories of working at Psygnosis’s American branch office in the early 1990s.

If you haven’t played Lemmings before, you’ve been missing out; this is one game everyone should experience. Feel free to download the original Amiga version from here. Amiga Forever is an excellent, easy-to-use emulation package for running it. For those less concerned about historical purity, there are a number of versions available to play right in your browser.)