When they announced the first Telarium games to considerable press fanfare in 1984, Spinnaker Software promised that they would represent not just a new line of adventure games but a whole new approach to interactive fiction that would take the form beyond what even Infocom had so far achieved. The new Telarium philosophy was expressed in interviews by PR mastermind Seth Godin:

The adventure-game market has been pretty much the same since 1976, when the first adventure game came out. That is, they’ve been puzzle-based games, be they text or graphics — they’ve always been based on a series of logic puzzles.

We’re trying to make a game that is based on plot and characterization, not puzzles — the way a book is. If you read Fahrenheit 451, you don’t get stuck on page 50. And if you play the game, you don’t get stuck on frame 50, because the whole idea is that you’re interested in the game because of the characters and the plot and what’s happening. You care about what’s going on.

In short, Telarium promised to “replace puzzles with character-oriented situations.”

Anyone who had been working with adventure games for a while and thus knew what a difficult proposition that was had their skepticism amply justified when the first slate of Telarium games actually appeared near the end of the year. Rendezvous with Rama was, predictably enough given its almost bizarrely adventure-game-like source novel, exactly the “collection of logic puzzles” set in a deserted landscape that Godin had said Telarium wasn’t interested in making. Fahrenheit 451, Dragonworld, and Amazon all played out in more populated worlds, but used their non-player characters as window dressing or, at best, puzzle solutions and password vending machines. And thanks largely to a parser that was truculent even by the standards of the era, Fahrenheit 451 in particular was full of exactly the sort of opportunities to get infuriatingly “stuck on frame 50” that Godin had promised wouldn’t be there. The games just didn’t live up to the hype.

All of which made the next two releases in the line, which trickled out almost a year after that initial glut, doubly surprising. Both Perry Mason: The Case of the Mandarin Murder and Nine Princes in Amber try much more earnestly to do the sorts of things that Godin had been talking about all along. Indeed, their character-interaction ambitions and determination to turn the adventure game into genuine interactive fiction exceed even Infocom’s farthest voyages into those fraught realms. Mind you, their ambitions don’t reach anything close to fulfillment, and can be read as an object lesson in the reasons that Infocom chose to shy away from similar projects in the name of crafting playable games. Still, their determination to push the boundaries make them if nothing else some of the most interesting games of their era.

These games can also serve as an object lesson in just how quickly the times can change. By the time they appeared ominous warning signs had turned into a full-blown home-computer-industry slump from which nothing suffered more than the nascent phenomenon of bookware. Perhaps due to the disappointing sales of that initial slate of games (from which, only and oddly, Michael Crichton’s Amazon was excepted), Byron Preiss and his team of talented young writers and illustrators had parted company with Spinnaker, taking with them an apparently all but complete game based on Robert Heinlein’s Starman Jones as well as deals in the works with the likes of Philip José Farmer and Alfred Bester. Undaunted, Spinnaker took creative as well as technical ownership of Perry Mason and Nine Princes in Amber in-house; both games are products of committees, including in the case of Perry Mason no fewer than four people — among them the irrepressible Mr. Godin — writing the “scripts.” Whatever the usual merits of such an approach, in this case it results in no noticeable drop-off in quality or ambition. Whatever else you can say about them, these games are no camels.

The original creator of Perry Mason, Erle Stanley Gardner, can stand proudly alongside Dennis Wheatley as one of the great bad writers of the twentieth century, his life story a monument to sheer dogged persistence more so than any innate talent. A rather abrasive personality cut in the classic can-do American mold, he passed the bar and became a lawyer in 1911 without ever darkening the door of a law school. He turned to writing action, adventure, detective, and science fiction with the arrival of the pulps in the 1920s. Showing the commitment with which he approached everything he attempted, he forced himself to churn out 4000 words per night, 1.2 million per year. He was unashamed of his motivations: “I write to make money, and I write to give the reader sheer fun.” When questioned why his heroes always seemed to finish off the bad guy at last with the last bullet in their guns, Gardner said, “At three cents a word, every time I say ‘Bang’ in the story I get three cents. If you think I’m going to finish the gun battle while my hero still has fifteen cents worth of unexploded ammunition in his gun, you’re nuts.”

Once his finances allowed, Gardner further refined his approach to writing, hiring as many as six secretaries to whom he dictated outlines of his stories for completion and polishing; this literary assembly line earned him the sobriquet “the Henry Ford of detective fiction.” By the time of his death in 1970 his oeuvre was so huge and published in such diverse and often ephemeral places as to be virtually uncatalogable. It includes at least 150 novels, at least 500 short stories, a significant body of nonfiction writing (largely on travel and history) for the glossy magazines, radio and television scripts. His sales in his heyday were equally enormous: at one time the Guinness Book of World’s Records could name him nothing less than the best selling writer of all time.

For all that productivity, Gardner would be regarded, like Wheatley, as little more than an historical curiosity today were it not for a single member of his large stable of lawyers, private eyes, and adventurers: Perry Mason. The redoubtable lawyer first appeared in 1933 as the star of the novel The Case of the Velvet Claws. That version of Mason was created in the hard-boiled image of Sam Spade: a two-fisted brawler who’s all about the money his services will earn him and isn’t afraid to resort to blackmail to achieve his ends. But as time passed and Gardner and Mason made the transition from the rough-and-tumble world of the pulps to the more genteel environs of the Saturday Evening Post, Gardner’s Mason gradually softened into something in at least the same zip code as the glibly savvy do-gooder soon to become a fixture of American television.

In the years before that star-making turn by Raymond Burr, Perry Mason was adapted many times into other media, including a string of low-budget movies and a long-running radio serial. Like the novels themselves, all are largely forgotten today, along with the many actors who portrayed Mason in them. But when Gardner saw Burr audition for the television version in 1957, he just knew he’d found his man at last: “Raymond Burr is Perry Mason!” he declared. Aside from a brief, ill-considered stab at the role by Monte Markham in 1973, no one but Burr would ever dare play Perry Mason again.

Burr’s Mason became one of the most enduring characters in the history of television, lasting through not only the original series’s staggering 9-year, 271-episode run (they cranked ’em out quick in those days) but also a series of 26 well-received television specials broadcast between 1985 and Burr’s death in 1993. He remains a fixture of daytime syndication schedules today, his theme song still immediately identifiable as soon as it comes over the airwaves (or cable line, or Internet…). The televised version of Mason came to entirely supersede his print counterpart, to the extent that even many loyal viewers of the television series then and now don’t realize that there ever was a Perry Mason before Raymond Burr.

Which brings us back to Telarium’s adaptation. Telarium was of course supposed to be a line of book adaptations. Spinnaker had already demonstrated what contortions they would go through to uphold the bookware concept with Shadowkeep, for which they hired Alan Dean Foster to write an inconveniently absent source novel. Still, no one in 1985 was interested in playing a game based on Gardner’s Perry Mason novels, which had largely fallen out of print and into obscurity following his death in 1970. So what we have is a hybrid that duly plays homage to the bookware concept by featuring the name of Erle Stanley Gardner prominently on the cover along with a nice “about the author” blurb to describe him, but which is otherwise an unabashed re-creation of the television version. This Mason is clearly Burr’s Mason. Not only does he feature on the package cover, but his colleagues and opponents in the in-game illustrations are perfect likenesses of the actors who portrayed them on television. The game even opens with a computerized rendering of that iconic theme song.

For obvious reasons, the polite fiction that the authors of the Telarium source materials were all intimately involved with their adaptations is here quietly but definitively dispensed with. This is a licensing deal, pure and simple, with the Gardner estate’s Paisano Productions holding company also getting its name on the box, albeit in the copyright fine print. The timing must have seemed perfect to both Spinnaker and Paisano: Perry Mason’s star was suddenly rising in the wider culture, thanks to the first of that series of television revivals that brought him back to prime time for the first time in many years just as the game was being published.

The game’s case could have fit easily into either the television show or one of Gardner’s books. Your client, one Laura Kapp, was apprehended by the police in an insentient state in her apartment with a gun lying just a few feet away — the same gun, in fact, that killed her husband Victor, who was found lying across the room. It seems that Laura was just released from a mental hospital and was extremely jealous as well as unstable, and for good reason: it appears that Victor was conducting at least one affair in her absence. Open-and-shut case, right? Anyone who says yes has never seen an episode of Perry Mason; the fellow amassed a final record of 268 to 3 (with one defeat later overturned on appeal) on television getting clients out of equally tough spots.

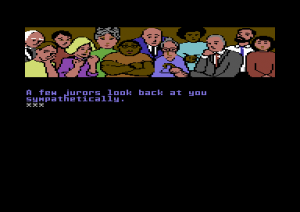

But if The Case of the Mandarin Murder is a fairly typical episode of Perry Mason, it’s a very atypical adventure game, minimizing or dispensing entirely with some of the most established conventions of the genre, among them object-oriented puzzles, mapping and (geographical) exploration, even compass directions. The first part of the game, during which you search the Kapp apartment for clues under the watchful eyes of the police, is the most traditional. But that is only a prelude to the real meat of the experience, which plays out as a series of examinations and cross-examinations in the courtroom. Just as in the television show, you’ll need to direct your faithful colleagues Paul Drake and Della Street to follow up the leads that emerge in the apartment and over the course of the trial; they’ll often be running in to give you vital information in the very nick of time. Also present are Mason’s usual long-suffering foils, Police Lieutenant Arthur Tragg and District Attorney Hamilton Burger (one can’t help but wonder, given his record against Mason alone in the most open-and-shut of cases, how the latter in particular manages to keep his job). And then there are of course this episode’s guest stars and potential suspects, in the form of Laura herself along with the mysterious femme fatale with whom Victor was supposedly conducting his affair, Victor’s business partner and said partner’s wife, a restaurant critic with a grudge, and a doorman with a shady past. The trial can go in many different directions, with various final outcomes possible. It’s not that hard to amass enough evidence and cast doubt on enough testimony to gain a hung jury or even an acquittal for Laura. But to unmask the real culprit and force a patented Perry Mason confession amidst a hail of tears and recriminations… aye, there’s the rub, for both the right and the wrong reasons.

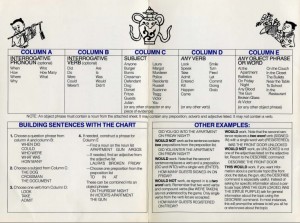

If you read my articles about the earlier Telarium games (or, better yet, if you’ve played any of them), you may be wondering how Telarium’s problematic parser fares in a production as dependent on character interaction as this one. The answer is, slightly better than you might think, but still nowhere near well enough. It’s not that the folks at Spinnaker, perhaps still stinging from criticisms of the parsing in those earlier games, weren’t aware of the challenge. Why else would they include in the package an elaborate and really quite clever “Mandarin Menu” which includes not only a vocabulary list but also a sentence-building chart for phrasing your interrogations?

Still, it doesn’t work out all that well. Many queries, including plenty that seem to comply perfectly well with the chart, fall flat. It’s just way too hard to figure out how the game wants you to phrase things, what keywords — and remember we’re dealing here with lots of abstract subjects like feelings and affairs and alibis — it wants from you to trigger a response in a witness. Combine that with the stubborn lack of feedback typical of the Telarium parser, and you end up with a feeling all too common in interactive fiction, that of never being sure whether a given line of questioning is really unproductive or whether you’re just not phrasing things correctly. In other words, is this witness shaking his head at you for diegetic reasons, because his answer is really no, or is he doing it because the extra-diegetic parser doesn’t understand you? To further complicate matters, you’re constantly being graded by the jury on your competence, confidence and flair for courtroom drama. As soon as you start to bumble and stumble around up there the game is up. Thus playing becomes a matter of experimenting on each witness to figure out what she can understand and what you can get from her, then restoring to play the polished and all but omniscient Mr. Mason we know from television.

Another problem is more subtle than the war with the parser. The solution to the case, when it finally emerges, is convoluted and, well, pretty much ridiculous — hardly an anomaly in the world of Perry Mason. The problem in the context of a Perry Mason game, however, is that it’s effectively impossible for you to ever arrive at it until the guilty party breaks down and confesses. With no real hard evidence pointing to that guilty party, you’re largely left to just hammer on everyone until somebody finally cracks. You’re rather left in the position of the would-be know-it-all detective in Simon Christiansen’s modern interactive fiction Death Off the Cuff. Yet whereas that game knows what it’s doing and, indeed, is meant as a send-up of absurdly omniscient detectives just like Perry Mason, this game is not so knowing. Believe me when I say that the solution totally comes out of left field — and is totally stupid at that.

Another thing about the case, not so much annoying as just strange: while Victor was a prominent restauranter, nothing “Mandarin” has any real bearing on the case. The subtitle is apparently a reference to the restaurant Victor was planning to open next, but said restaurant isn’t germane to much of anything about the actual murder. About the best thing you can say about it is that it allows for that neat “Mandarin Menu” of sentence composition, a sort of backdoor homage to the hacker’s traditional love for Chinese food. (The subtitle could also be taken as an advertent or inadvertent homage to Gardner himself, who built his early law practice defending the rights of Chinese immigrants. He remained fascinated by China throughout his life, visiting the country several times and allegedly building up a passable proficiency in Cantonese, no mean feat for a Westerner.)

So, no, The Case of the Mandarin Murder doesn’t entirely work as game or as courtroom drama. Yet it’s nonetheless kind of fascinating for what it tries to do as well as for the way it tries to do it. Although it sprawls across the four disk sides typical of all the Telarium games, a single playthrough is unlikely to take much more than two hours (or maybe three if you play the Commodore 64 version I’m making available for download here, what with that machine’s painfully slow disk access). It’s implemented in depth rather than breadth, loaded with details to be uncovered and secrets to be discovered. Sure, some of the Easter eggs are just silly; the dumbest plays on the fact that one of the characters is named Julian, same as a character in Telarium’s contemporaneous Nine Princes in Amber game.

But that sort of silliness is more the exception than the norm. Better are the moments here and there when the parser does understand you for a few turns at a stretch and you really do feel like Perry Mason up there jabbing and feinting at the witness and playing it up for the jury. Those moments, if not quite enough to make it worthy of an unabashed recommendation, are more than enough to make me toast its ludic dreams and ambitions nobly striven after if ultimately unfulfilled.

(Sorry for the long delay between posts, as well as this site’s going offline for a day or two recently. My mother suddenly and unexpectedly died, which led to lots of emotional turbulence and a frenzied trip back to America. In the midst of all that I neglected to renew my domain registration. Things will hopefully now be settling back into a normal rhythm.

Sources on Telarium this time out were pretty much the usual referenced in previous articles, especially the December 1984 Compute!’s Gazette and the June/July 1985 Commodore Power Play. A couple of interesting summaries among many of Erle Stanley Gardner’s life and career can be found at Thrilling Detective and at the website of his long-term home town of Temecula, California. And thanks as always to C. David Seuss for sharing some of his memories and some valuable resources from the glory days of Spinnaker Software.)