Warning: this article contains images of pixelated male genitalia.

On December 9, 1993, members of the United States Senate’s Subcommittee on Regulation and Government Information and its Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice held a joint hearing on the topic of violence and sex in videogames. Educators, social scientists, activists, and several prominent figures from the videogame industry itself spoke there for almost three hours. More heat than light was on display for much of that time: the middle-aged politicians often displayed a comprehensive ignorance of the subject at hand, the supposed experts often treated nuanced issues with stubborn stridency, and the industry figures often proved more interested in attacking each other than mounting a coordinated defense against the charge of being the corruptors of America’s youth.

But history sometimes moves in surprising ways. The hearing prompted far-reaching changes in gaming out of all proportion to its worthiness as a good-faith debate about a significant social concern. The first and to-date only industry-wide standard for rating the content in videogames — the same system that is still in use today — was one outcome. And another, much stranger result was the splashy trade show that has since come to dominate the industry’s public-relations calendar. One might say that December 9, 1993, was the day that the games industry began to wake up to a sense of itself as a distinct mass-media entity in its own right.

This is the story of how those things came to be.

Videogames have been causing intermittent moral panics for almost as long as they’ve existed. The first of them to ignite public ire dates all the way back to 1976 and a small company called Exidy. The year before, Exidy had made a standup-arcade game called Destruction Derby, about the time-honored American motorsports pastime of the demolition derby, a staple of county fairs and other rural gatherings. When Chicago Coin, the company who had agreed to distribute the game to arcades, failed to pay them their royalties, Exidy revamped it into something called Death Race and released it on their own. Instead of other cars, you were now expected to collide with stick figures, called “gremlins” or “monsters” in Exidy’s official terminology, in order to score points. When you hit one, it was replaced with a little gravestone.

As it happened, though, a recent B-movie called Death Race 2000 was generating enraged headlines at the very same time. Starring a pre-Rocky Sylvester Stallone, it dealt with a cross-country road race of the dystopian future where the drivers were rewarded with bonus points for mowing down pedestrians en route. It’s very difficult to say what the connection between the film and the game actually was. The programmer who created the latter has insisted to this day that he was unaware of the movie at the time he did so. Still, the shared title remains quite a coincidence. Perhaps a marketer at Exidy belatedly elected to capitalize on the film’s notoriety by giving the already finished game the same name?

At any rate, the shared title certainly wasn’t lost on the media at the time. Several television-news programs, including the highly respected nationwide 60 Minutes, ran segments about the game after receiving a flood of complaints from parents and other concerned adults, and many or most arcade owners removed it from their floor. Nolan Bushnell, the founder and chief executive of industry leader Atari, was very displeased with the negative attention Death Race brought to a burgeoning new form of entertainment: “We had an internal rule that we wouldn’t allow violence against people. You could blow up a tank or you could blow up a flying saucer, but you couldn’t blow up people. We felt that was not good form.” But Pete Kaufman, the founder of Exidy, was unrepentant. Those arcade owners who weren’t scared away by the controversy, he noted, did a booming business with Death Race.

The young industry was already learning an important lesson: that extreme violence in a videogame is dangerous because of the unwanted attention it can attract, but that it also has the potential to be very, very profitable. The industry’s future would be marked by a delicate dance between these two realities, as it attempted to be outrageous enough to attract customers with a taste for violence without going so far as to bring the heavy hand of government down upon its head.

Atari and their American and Japanese competitors went from strength to strength in the years after Death Race. First arcades became centerpieces of adolescent social life, and then, thanks to the Atari VCS home console, videogames took over American living rooms as well. The elder generation reacted to these things in much the same way that their parents had to such youth phenomena as Elvis and the Beatles: with a shrug of complete incomprehension, followed in many cases by concerns about the influence of this strange new pop-culture development on their children’s mental and even moral well-being.

The city council of the Dallas, Texas, suburb of Mesquite went so far as to ban children from visiting arcades without an adult escort. A legal challenge raised by the American Civil Liberties Union in response made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which struck the law down as unconstitutional in 1982. Undaunted, Dr. C. Everett Koop, President Ronald Reagan’s unusually prominent surgeon general, became a vocal critic of videogames and an advocate for laws to limit their pernicious influence, claiming that they were consciously engineered to addict children, “body and soul.”

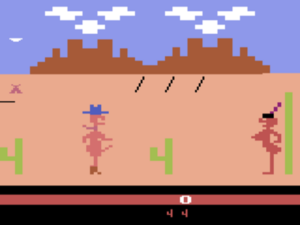

It’s an odd truism of American culture that, while violence in media may upset various people at various times, nothing brings out the censors in the body politic like a little sex. In October of 1982, a company called Mystique, with ties to the pornography industry, proved this once again with an Atari VCS game called Custer’s Revenge, which combined violence and sex, then added a concluding flourish of racism. In it, you played a reincarnation of the benighted general. His most prominent onscreen feature was his outlandishly long penis, which he used to rape the Native American women he found scattered about the battlefield, already helpfully tied to stakes.

Controversy had clearly been the whole point of the game, and it was rewarded with its full measure, managing to unite the American Indian Community House, the National Organization for Women, and Women Against Pornography for a shared protest outside the New York City venue where it was shown to the press for the first time. Robin Quinn of the last-named organization proclaimed, accurately enough, that the game “says that rape is not only a legitimate form of revenge but a legitimate form of entertainment.” George Armstrong Custer III came out of the woodwork to complain that his great-granduncle’s reputation was being “maligned,” while Atari filed a dubious lawsuit claiming that the very existence of the game on their console created a “wrongful association” in the minds of the public. Arnie Katz, the founding editor of Electronic Games magazine, remembers telling the leadership of the protest movement that “the best way to keep the game from selling is to ignore it.” In the absence of a willingness to heed that perhaps wise advice, Custer’s Revenge wound up selling about 80,000 copies, at $50 a pop. Two other, similarly tasteless “adult” games from Mystique attracted less attention from groups who largely spent their outrage on Custer’s Revenge, and, just as Katz had predicted, proved much less commercially successful.

Still, the arrival of games of this ilk would surely have led to more controversy and eventually to serious calls for legislation, if only what struck many as the passing fad for videogames hadn’t ended abruptly the following year, in the series of events that have gone down in history as the Great Videogame Crash. By the beginning of 1984, the arcade market was greatly diminished, the home-console market effectively destroyed. For the next few years, for the first and only time in the history of digital gaming, computers rather than consoles became the most popular way to play games in the home; the Commodore 64 home computer became the new heart of the gaming mass market.

But even that machine, ultra-popular though it was as a computer model, wasn’t a patch on what the Atari VCS had been. Likewise, the market for floppy-disk-based entertainment software was a small fraction of the size of the former market for console cartridges — so small that it existed out of the sights and minds of the sort of public agencies that had raised concerns about the videogames of the earlier era. Thus software publishers felt little or no compunction about including whatever content struck their fancy and seemed most likely to appeal to their primarily young and male audience. Strip-poker games, many featuring digitized photographs of real models, were a dime a dozen; casual profanity was everywhere; the CRPG Wasteland gave you the option of visiting a house of ill repute (and catching “Wasteland herpes” as a reward for your effort).

Sometimes the lack of condemnation from the fuddy-duddy set could be downright frustrating. When Steve Meretzky of the text-adventure maker Infocom failed to generate any controversy with A Mind Forever Voyaging, his brutal take-down of the Reagan administration’s conservative politics, he decided to make a sex comedy called Leather Goddesses of Phobos. He confidently expected that, as he wrote in the game’s self-congratulatory opening text, people would soon be “indignantly huffing toward their dealer, their lawyer, or their favorite repression-oriented politico.” The actual result? Crickets — and a bunch of other adventure games, such as Sierra’s Leisure Suit Larry series, that were even naughtier, and included graphics to boot.

Sex Vixens from Space, one of many risque games that were eagerly played by adolescent boys during the games industry’s equivalent of pre-Hays Code Hollywood.

The return of concerns about videogame content to the public consciousness unsurprisingly coincided with the return of console systems, and the vastly greater number of players they’ve always tended to attract, to the center of the mass market. The Nintendo Entertainment System was first imported to North America from Japan in a rather quiet and cautious fashion in late 1985. But by 1987, it was gaining steam quickly, and by decade’s end its market penetration exceeded even that of the Atari VCS in its heyday.

The fact was, the executives at Nintendo, both those in Japan and in the United States, had made a careful study of what Atari had gotten right and wrong back in the day, and developed a plan for how they could do things in a better, more sustainable way. Nintendo exercised complete control over the NES and everything associated with it. They created an ironclad legal framework which allowed them to decide who was allowed to make NES games, what sort of games these were allowed to be down to the very last detail, and even how many cartridges their software “partners” were allowed to manufacture and sell. Then, as the icing on the cake, Nintendo took a cut of every NES game anyone sold. Not only did this approach make the company extraordinarily profitable, but it ensured that they wouldn’t have to contend with any examples of a Custer’s Revenge and the ensuing public-relations nightmare. Nintendo hewed to a firm “family-friendly” policy. Anecdotes about their censorship regime abound, from the swimsuit calendar which they forced LucasFilm Games to pull down from a wall inside Maniac Mansion to the gravestone crosses which Capcom had to remove from DuckTales — for, in Nintendo’s zeal not to offend, religious symbols of even the most understated stripe were strictly prohibited.

Nevertheless, plenty of Americans found plenty of room in their hearts to be offended by Nintendo’s success. In many cases, their concerns about the heavy-handed tactics which the company used to control both the medium and the message of the NES were perfectly reasonable. Still, a distinct whiff of xenophobia and/or outright racism clung to many of the criticisms, manifested in dark mutterings about the latest Pearl Harbor, couched in stereotypes about the shifty Oriental character. When Nintendo introduced the Game Boy handheld console in 1989 and saw it blow up as big as the NES, the mutterings threatened to become a chorus.

Believing that the winds of public opinion were at their back, Atari Games and Atari Corporation, the two halves into which the old king of American videogames had been split back in 1984, launched a series of legal challenges that attempted to tear down the barriers around Nintendo’s walled garden. These would drag on for years, but would never provide the decisive victory the deposed kings of gaming were looking for; they soon learned that Nintendo could afford good lawyers too. Ditto a probe by the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission; the smoking gun these would-be trust busters were looking for either didn’t exist or was very well-hidden.

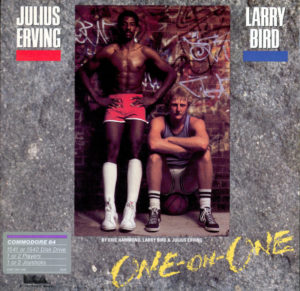

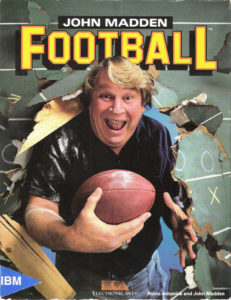

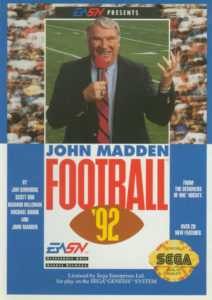

But there was also another reason that the government investigation fizzled out anticlimactically in 1992, two years after its beginning: Nintendo had some genuine competition in the console space by that point, making it hard for the agencies to stick them with the monopoly tag. The Sega Genesis console, another product of a Japanese company, had first reached American shores in August of 1989. It thoroughly outclassed the NES in technical terms, with a 16-bit rather than an 8-bit processor and far better graphics and sound. Justifiably alarmed, Nintendo did everything they could to snuff out Sega’s North American operation, pressuring everyone from game publishers to retail stores to shun the alternative platform or face the consequences. Their efforts kept Sega on the ropes for quite some time, but Nintendo never could completely finish the job. A turning point came when Electronic Arts, one of the largest American game publishers, chose to make Sega rather than Nintendo their platform of first choice.

By 1992, following years of dogged effort, Sega had brought their brand to a place of near commercial parity with Nintendo, despite the appearance in 1991 of a new Super NES which made up for most of the NES’s failings in comparison to the Genesis and then some. Sega owed their success at least partially to their willingness to embrace edgier and often more violent content, pitched to a slightly older adolescent demographic than the stereotypical Nintendo fanatic. The differences in corporate personality were vividly illustrated by the two companies’ de-facto mascots. Nintendo’s Mario was cute and sweet and harmless; Sega’s Sonic the Hedgehog was manic and a little unhinged — a little bit more dangerous than the cuddly Italian plumber. Sega didn’t hesitate to call out their target by name: “Sega Genesis does what Nintendon’t,” ran one of their most-used slogans. But it could just as easily have read, “Sega Genesis does what Nintendo won’t,” in terms of content. The two companies’ North American management absolutely loathed one another. Soon they would parade their antipathies before no less august a body than the United States Senate.

Although that landmark hearing would purport to examine questionable videogame content in general, its story is inextricably bound up with that of two games in particular, as different from one another as they could be in their genres, format, and to some extent even the audiences they attempted to reach. One was notable for its extreme level of violence, while the other was notable for its combination of sex and violence — or rather was made notable by politicians and others who convinced themselves that it contained far more of both than was actually the case. We’ll take the two suspects one at a time.

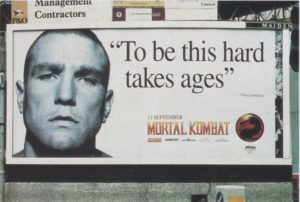

Arcades were still blundering along at this late date, sustained by the impressive audiovisuals that were made possible by their specialized hardware, which not even the likes of the SNES could match. By far the biggest arcade hit of 1992 was a game called Mortal Kombat, the latest in what was already a long line of so-called “fighting games.” (“Aren’t most videogames fighting games?” says the naïve observer…)

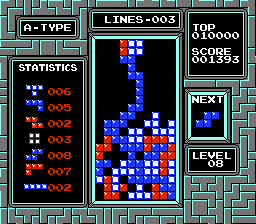

The premise was simplicity itself: you and an opponent — in the form of either the computer or, for maximum entertainment, your human buddy — controlled avatars who stood face to face on the screen and beat the ever-loving crap out of one another. Mortal Kombat won special favor in a crowded field for the variety of fighters you could choose to control, each with his or her own strengths and weaknesses; for its many moves, counter-moves, and power-move combinations; for its rambunctiously over-the-top depiction of the action, including copious amounts of blood; and for the so-called “fatalities” that finished a match, where a fighter’s heart might get pulled right out of his chest or his head ripped off his shoulders. Jeff Greeson, a student of the game and its lore, notes that “Mortal Kombat not only shocked anyone who had ever played the game, but those who simply walked by the game were mesmerized by its gore.” No arcade game had ever been as extreme as this. How could it not become a hit?

The life cycle of a hit arcade game in those days was much like that of a hit movie: it would remain an arcade exclusive for nine to twelve months in order to maximize that revenue stream, then come home in a version for consoles and/or computers. Midway Games, the maker of the original Mortal Kombat arcade cabinet, placed its home ports in the hands of the software publisher Acclaim Entertainment, who had contracts with both Nintendo and Sega. True to form, Sega encouraged Acclaim to put in as much of the arcade edition’s lurid violence as would fit within the more limited audiovisual capabilities of the Genesis. But Nintendo was different: while they certainly wanted the game on the SNES, they insisted that Acclaim tone it down — for example, by replacing flying blood with flying sweat, and by removing the gory fatalities entirely. Howard Lincoln, a Nintendo of America executive who is widely and justly regarded as one of the two principal architects of the brand’s success, remembers an extended back-and-forth with Acclaim over the issue: “Look, we’re going to make the Sega version, and it’s going to be right in line with the coin-op game. Having a toned-down version for Nintendo… Do you guys really want us to do that? Does that really make sense?” But Nintendo held firm to the family-friendly standards that had gotten them this far.

Versions of Mortal Kombat for the SNES, the Game Boy, the Genesis, and the Game Gear — the last being Sega’s handheld competitor to the Game Boy — shipped simultaneously on September 13, 1993, on the back of a marketing budget that was higher than the combined cost of creating them. Just as Acclaim had intended, “Mortal Monday” became a major event in the lives of countless young fans, who greeted the game the way their parents might have a new Led Zeppelin album. The merchandising manager of Electronics Boutique, one of the country’s biggest videogame retailers, called it “the largest new release we’ve ever had.” Later that week, the New York Times could already report that the Sega versions were handily outselling the Nintendo versions.

Whether you were into videogames or not, Mortal Kombat was an inescapable mass-media presence during the autumn of 1993.

Over the next two months, 1 million SNES Mortal Kombat cartridges were sold. This was an impressive showing – except that 2 million Genesis cartridges were sold over the same period. It was a triumphant moment for Sega, who had struggled so long and hard to reach this point, even as it struck Nintendo’s management as the most palpable sign yet that they were in danger of being dismissed as a kiddie company by the teenagers who were now flocking to Sega, bringing along with them their greater reserves of precious disposable income. For the first time, a serious internal debate began at Nintendo over the commercial sustainability of their family-friendly approach.

Despite or because of its outrageous violence, Mortal Kombat was and is a good game in the estimation of most connoisseurs of its genre. Even if it had never prompted a public controversy, it would probably still be fondly remembered by them today; it proved the starting point of a franchise that has encompassed thirteen more games to date. But the other game destined to take center stage before the United States Senate was not so good, and would almost certainly be completely forgotten today if not for its strange moment of infamy in the halls of government.

If nothing else, the game in question does have a fascinating origin story. It begins with Tom Zito, a journalist and music critic for the Washington Post, Rolling Stone, and the New Yorker, who in 1984 was assigned by the last of these to profile Nolan Bushnell of Atari fame. He parlayed that meeting into a job with the Sunnyvale, California-based Axlon, one of the legendary technologist’s several companies, marketing baby monitors and talking Teddy bears which were distributed by the toy giant Hasbro.

But Bushnell always encouraged his proteges to think expansively rather than narrowly. Thus early in his tenure with Axlon, Zito allowed himself to become intrigued by the new video technology of the laser disc, and by the possibility of overlaying conventional computer graphics onto its pre-recorded random-access imagery. In 1986, he stumbled upon the NES and the burgeoning excitement around it during a routine visit to a department store. Deciding that a laser-disc-powered videogame console was just the ticket, he hired a small team to cobble together a Rube Goldberg contraption they called the Nemo. When the limitations of laser discs began to bite — they could fit only 30 minutes of video onto a side, and the hardware was expensive to boot — they tried to make the concept work with the even blunter instrument of a videotape player under the control of an attached computer. “What I truly believed was that interactive television could be something akin to today’s casual gaming,” says Zito. “I really believed it could be something very, very big.” But Bushnell, alas, displayed more and more skepticism as the technical challenges to the concept became more and more clear. So, Zito secured support directly from Hasbro to develop the gadget further, and he and his team of programmers and engineers split from Bushnell to work on it independently.

They decided that the best way to proceed was to create a full-length, playable game to demonstrate the potential of the Nemo. But what kind of game could they hope to make, given all the limitation of their prototype hardware?

As it happened, a game destined to go down in history as one of the schlockiest of all time was inspired by a much more high-brow piece of artistry. An experimental theatrical play called Tamara was enjoying an extended run at the time in a grand old American Legion mansion in Hollywood. Instead of sitting in one place and watching the show unfold on one stage, the audience could move around the mansion’s three floors on the trail of equally mobile actors; each spectator was encouraged to decide for herself which of the play’s many characters and sub-plots were most interesting and to see them through for herself, as it were.

Two of Zito’s associates, by the names of Rob Fulop and Jim Riley, went to see the play in question one evening. Then they saw it again, and then again. This was not atypical in itself: with so much happening simultaneously, the only way to piece together anything like the complete picture was to attend multiple performances. Yet the precise nature of Fulop and Riley’s curiosity was unusual: rather than trying to piece together the full plot, they were trying to understand how the play really worked, and how its approach might be adapted to interactive video. When they thought they had an understanding of those things, they produced a design document for something called Night Trap.

Night Trap was a bizarre creation by any standard, being the (interactive) story of a group of vampires in training who attack a mansion full of college girls having a weekend sleepover party. Not yet having won their fangs, the vampires have to suck the girls’ blood with a weird contraption of plastic tubing. These are unusually diffident — not to say nerdy — vampires: instead of overpowering the girls bodily, they’ve installed a network of surveillance cameras in the house, along with traps which they can activate remotely to capture the girls for blood extraction. The player’s role is that of a good Samaritan who has hacked into the surveillance system, with the goal of turning the tables on the vampires and catching them in their own booby traps. While by no means completely bereft of a certain creepy voyeuristic vibe — how could it be when it combined college girls in their pajamas, vampires, and a secret surveillance system? — the final script was far from sexually explicit, and likewise more silly than violent. The developers did, after all, envision the game someday being sold by Hasbro, a maker of children’s toys. Indeed, they allowed that company’s management to review the script and remove or change anything they found objectionable.

Fulop, Riley, and Zito spent sixteen days in 1987 shooting the footage for the game with a Hollywood crew that included the future cinematographer of Forrest Gump and the former producer of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. The shoot wound up costing $1 million, several times the budget of even the most elaborate conventional videogames of the time.

For all the richly deserved schlocky reputation which it would later earn, Night Trap was a genuinely pioneering effort in its way. The combination of real-world footage featuring real actors with conventional graphics would become one of the dominant trends of computer gaming during the early- and mid-1990s. Many of the dubious hallmarks of this so-called “full-motion-video” era appeared for the first time in Night Trap. There was, for example, the way that it tried to make up for the cheesiness that was an inevitable result of its ultra-low cinematic budget by affecting a knowing, ironic attitude — i.e., it’s supposed to be terrible! That’s the joke? Get it? Well then, what are you complaining about? This sort of thing can work occasionally, but most of the time it just comes across as the cheaply disingenuous ploy it really is.

And then there was the use of actors who were vaguely recognizable, but not — or no longer — truly sought-after. “Interactive ‘moviegames’ were populated by performers either on their way up or on their way down the Hollywood ladder,” says Rob Fulop. “Nobody aspired to appear in a moviegame.” Night Trap‘s big catch was Dana Plato, a young actress who had had a prominent role in the hit sitcom Diff’rent Strokes from 1978 until 1986, but whose struggles with alcohol and drugs, and the erratic behavior they brought on, had now all but derailed her career. “She’d come in late and never wanted to rehearse,” remembers Fulop. “Her doing this project was obviously a step down from her previous popularity, and she didn’t make a great deal of effort to hide this fact.” This sort of thing too would become all too typical of later interactive movies.

When the shoot was complete, the developers returned to Sunnyvale to try to figure out how to turn their pile of videotapes into a playable game on the Nemo. In the best spirit of Tamara, you were supposed to be able to switch between the video feeds from eight different cameras set up around the mansion; you would need to be in just the right place at just the right time to trigger a trap and catch each of the vampires. But making this random-access concept work using the fundamentally sequential medium of videotape was, needless to say, a tall order.

Amazingly, Hasbro allowed Zito and company to shoot the footage for a second interactive movie while they were still struggling to implement their first one. Zito conceived Sewer Shark as a visual-effects extravaganza, and therefore gave the director’s chair to John Dykstra, the effects supervisor for such films as Silent Running, Star Wars, and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. He spent most of his time setting up shots of the tunnels down which the player would fly a spacecraft; think of an interactive-movie version of the later 3D action game Descent, if your imagination can encompass such a thing. Any way you look at it, Sewer Shark is a well-nigh ludicrous technological stew. Just as Hollywood was beginning to embrace computer-generated imagery in place of many physically-constructed special effects, Sewer Shark flipped that formulation on its head; it was filmed using old-fashioned physical scale models, which were then digitized and displayed on a computer. Shot in exotic Hawaii for reasons no one can seem to explain, the Sewer Shark footage wound up costing $2 million.

When not supervising film shoots, Zito was spending a lot of time hobnobbing with the Hollywood set, trying to interest them in a concept that still had no practical delivery device. He talked to Jane Fonda about an interactive workout video; talked to Jerry Bruckheimer about an interactive Top Gun; talked to Paramount about an interactive Star Trek; talked to the rock band Yes about an interactive music video; talked to George Miller about an interactive Mad Max; talked to ESPN about interactive sports broadcasting. He even flew to London for a meeting with Stanley Kubrick. None of it went anywhere.

It isn’t clear how much progress his technical team made on the task of turning Night Trap and Sewer Shark into playable games on the Nemo while he was away. We can say for sure, however, that their progress wasn’t fast enough for Hasbro’s taste. The latter came to suspect, by no means entirely unreasonably, that Zito was more interested in enjoying his Hollywood jet-setter lifestyle than buckling down and delivering the finished product he had promised them. They finally pulled the plug on the Nemo in 1989 — ironically, just as the evolution of computer technology, especially the onset of CD-ROM, was beginning to make what Zito had first proposed to do some three years before seem at least potentially practical. But Zito, for his part, was well aware that the science-fictional was slowly moving into the realm of the possible. He convinced Hasbro to sell him the rights and all of the footage earmarked for Night Trap and Sewer Shark for a song.

Two years later, what had once seemed so pie-in-the-sky was now striking many people who weren’t named Tom Zito as gaming’s necessary future. That year, there appeared Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective, the first published game to make extensive use of filmed live-action footage. It did very, very well.

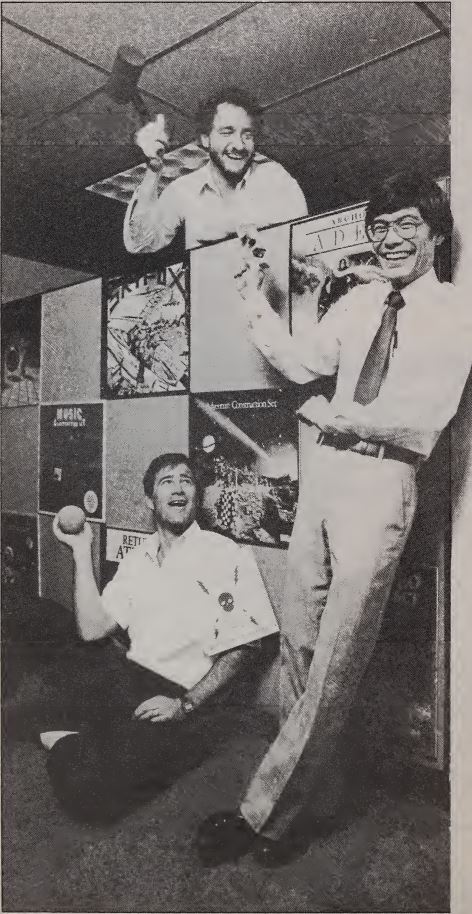

Suddenly afraid that his five-year-old brainstorm was about to take off without him, Zito founded a company called Digital Pictures. Its first objective would be to make a pair of interactive movies built around the live-action footage which he had carried away from the Nemo project. His rhetoric, once so bizarre, was now right in line with the emerging conventional wisdom: “Ultimately, I believe the [videogame] business will be more like traditional Hollywood stuff than what’s coming out of Silicon Valley today: some dinky animated guys running around the screen. We’ll be doing interactive game shows, talk shows, dramas, sitcoms.” “Why watch a movie where you can’t have any effect over it?” asked the Digital Pictures artist Josh Solomon. “Why not be able to put your own stamp on it?”

There was one important difference to separate Digital Pictures from most of the others jumping on the full-motion-video bandwagon. These others tended to focus on the high-end personal-computer marketplace, where CD-ROM drives were slowly but steadily winning acceptance, and where the hardware in general dramatically outclassed that of the consoles. But Zito was a mass-media populist by instinct; he wanted to bring his interactive movies to the living rooms of everyone, not just to the dens, offices, and bedrooms of a privileged few.

Both Nintendo and Sega were also aware of CD-ROM, and both were contemplating whether and how they could use the technology. But the former, after first partnering with Sony to make a CD-ROM add-on for the SNES, abruptly pulled out of the deal; an optical drive wouldn’t finally make it to a Nintendo console until the release of the GameCube in 2001. Nintendo’s abandonment of the field left only Sega, who planned to make a CD add-on of their own for the Genesis. So, Zito signed on with them.

Re-purposing the aged footage wasn’t easy. First it had to be digitized, then downgraded dramatically to fit a venerable console that in all truth was thoroughly unsuited to the task it had been assigned: it could display just 61 colors at a time from a palette of just 512. Compared to the full-motion-video productions on personal computers — not exactly marvels of high-fidelity in themselves — Sewer Shark on the Genesis was a bad joke. Digital Pictures programmer Ken Melville:

All our video had to be tortured, kicking and screaming, into the most horrifying, blurry, reduced-color-palette mess imaginable. I shudder to think about it. The audio, the video, the accessing of data on the sloooow-crawling 10 K per second bandwidth CD was all torturous and disastrous. The limitations presented were enormous.

The actual gameplay that was shoehorned in on top of the video was as simplistic as could be, consisting of little more than cross-hair and some grainy targets to shoot at.

Sega’s CD add-on shipped on September 15, 1992; the two-and-a-half minute television advertisement that was rolled out to mark the occasion had cost more to make than three or four typical videogames. The gadget had sold 1.5 million units by the time anyone managed to complete the first tally. As one of the first games to be made available for Sega CD, Sewer Shark did very well. In 1993, it was bundled with the add-on for a period of time, thereby making a lot more money for Digital Pictures.

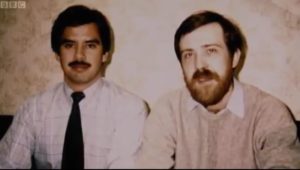

Night Trap appeared soon after Sewer Shark. It was more formally ambitious than the simple rail shooter that was Sewer Shark — the original, Tamara-inspired gameplay concept had traveled the long and winding road to the Genesis intact — but it was no more attractive to look at and no more fun to play, being in the end an exercise in trial and error and rote timing. Predictably enough, the magazine reviews fixated on the novelty of its use of video and the nubile girls it featured so prominently, and especially on Dana Plato’s starring role. Over the five years since the footage had been shot, she had become one of Hollywood’s most infamous burnouts, having recently been arrested twice: once for robbing a liquor store (“I’ve just been robbed by the girl who played Kimberly on Diff’rent Strokes,” said the clerk when he phoned the police), then again for forging a drug prescription. But even her involvement constituted a paltry — not to mention rather mean-spirited — ground for playing a game, as some of the more perceptive or less beholden reviewers reluctantly acknowledged.

Night Trap. Dana Plato stands to the viewer’s left. She died of a drug overdose in 1999 at age 34, after an intensely troubled life.

Night Trap didn’t sell in particularly big numbers in comparison to its predecessor. Had it never come to a certain senator’s attention, it would doubtless have become no more than a minor footnote to gaming history, like the rest of Digital Pictures’s underwhelming output. As it was, though, it got to join Mortal Kombat as the public face of videogame depravity.

According to his own account, Joseph A. Lieberman, a United States Senator for the Democratic Party from the state of Connecticut, first heard about Mortal Kombat when his chief of staff Bill Andresen told the senator in casual conversation how his nine-year-old son had asked for a copy, and how he had refused because he had read in the newspaper that the game was “incredibly violent.” His curiosity kindled, Lieberman suggested that the two of them have a look at the game themselves. Lieberman:

I was startled. It was very violent, and rewarded violence. At the end, if you really did well, you’d get to decide how to kill the other guy, how to pull his head off. And there was all sorts of blood flying around.

Then we started to look into it, and I forget how I heard about Night Trap. I looked at that game too, and there was a classic. It ends with this attack scene on this woman in lingerie, in her bathroom. I know that the creator of the game said it was all meant to be a satire of Dracula, but nonetheless, I thought it sent out the wrong message.

Of course, the player’s objective in Night Trap was to protect the girls rather than attack them, and the nerdy trainee vampires were unusually non-violent by the traditional standards of their kind. Yet Lieberman would continue to spout misleading statements like these for months to come — before, during, and after the Senate hearing on videogame content which he instituted and oversaw.

In light of his manifest ignorance, many have questioned the senator’s own professed origin story of his investigation; did he and his chief of staff really have the wherewithal to go out and buy Mortal Kombat, buy or otherwise procure a Sega Genesis to play it on, and then get far enough into it to see its trademark fatalities? Tom Zito, for his part, claims that the investigation began in a very different way: that Nintendo, or one of their Washington lobbyists, arranged to show the good senator what sorts of filth their rival Sega was peddling. And indeed, the bad blood between the two companies was so pronounced that this conspiracy theory sounds more plausible than it perhaps ought to. We can say for sure only that, if Nintendo did touch off the affair in an attempt to stick it to their arch-rival, it would soon snowball hopelessly out of their control as well.

Naturally, we cannot hope to know what was really in Senator Lieberman’s mind in the midst of all this — whether he simply saw it as an easy way to win favor with his constituents (videogame players were not a large voting bloc in comparison to nervous parents and grandparents), or whether he really, truly felt the deep-seated concern he expressed on numerous occasions. In Lieberman’s defense, however, it should be noted that violent crime in the real world and its causes constituted a big part of Washington’s agenda that year and the next, in the midst of a spate of well-publicized incidents. For example, on October 1, 1993, a twelve-year-old girl named Polly Klaas was abducted from a slumber party in rural California at knife point, then murdered and buried in a shallow grave. Although the connection was never explicitly made during the Senate hearings, it isn’t a huge leap to presume that the slumber-party aspect of Night Trap may have been what tipped the balance and singled it out for so much overheated condemnation.

Whatever his motivation or combination thereof, Joseph Lieberman, chairman of the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee’s Subcommittee on Regulation and Government Information, reached out to his friend Herbert Kohl, chairman of the Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice. The two announced a joint hearing on the subject of videogame content and its effects on the psychology of children and adolescents, advertising it as the first step toward an eventual law that would require videogame publishers to mark any of their products which contained violent and/or sexual content on their boxes.

The videogame industry was about to get its day in a decidedly hostile court, with Mortal Kombat and Night Trap in the role of its two most flagrant offenders. The games made for quite the odd couple. Mortal Kombat was, for all its envelope-pushing violence, traditionalist in spirit, engineered to appeal to the teenage boys who had always been the biggest market for videogames; Night Trap, despite its manifestly clumsy execution, was an attempt to do something genuinely new in games, with the potential to appeal to new types of players. Mortal Kombat would later be remembered as a very good game; Night Trap as a very, very bad one. Mortal Kombat was a game whose content a reasonable person could reasonably object to in at least some contexts; Night Trap was most offensive in its sheer ineptness, and was hardly the grisly interactive slasher flick which Lieberman apparently believed it to be. Nevertheless, here they both were. December 9, 1993, would change the games industry forever.

(Sources: the books Dungeons and Dreamers: The Rise of Computer Game Culture from Geek to Chic by Brad King and John Borland, The Ultimate History of Video Games by Steven L. Kent, Generation Xbox: How Video Games Invaded Hollywood by Jamie Russell, and Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World by David Sheff; Edge of February 1994; New York Times of October 15 1982 and September 16 1993; Retro Gamer 54; the article “Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything” by Alex Wilcox in the Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary, Volume 31, Issue 1. Online sources include Kevin D. Impellizeri’s look back at the videogame hearings, “When Two Tribes Go to War: A History of Video Game Controversy” at GameSpot, “The 25 Dumbest Moments in Gaming” at GameSpy, and Shannon Symonds’s blog post about Death Race at the Strong Museum of Play’s website.)