The transformation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings from an off-putting literary trilogy — full of archaic diction, lengthy appendixes, and poetry, for God’s sake — into some of the most bankable blockbuster fodder on the planet must be one of the most unlikely stories in the history of pop culture. Certainly Tolkien himself must be about the most unlikely mass-media mastermind imaginable. During his life, he was known to his peers mostly as a philologist, or historian of languages. The whole Lord of the Rings epic was, he once admitted, “primarily linguistic in inspiration, and was begun in order to provide the necessary background history” for the made-up languages it contained. On another occasion, he called the trilogy “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work.” That doesn’t exactly sound like popcorn-movie material, does it?

So, what would this pipe-smoking, deeply religious old Oxford don have made of our modern takes on his work, of CGI spellcraft and 3D-rendered hobbits mowing down videogame enemies by the dozen? No friend of modernity in any of its aspects, Tolkien would, one has to suspect, have been nonplussed at best, outraged at worst. But perhaps — just perhaps, if he could contort himself sufficiently — he might come to see all this sound and fury as at least as much validation as betrayal of his original vision. In writing The Lord of the Rings, he had explicitly set out to create a living epic in the spirit of Homer, Virgil, Dante, and Malory. For better or for worse, the living epics of our time unspool on screens rather than on the page or in the chanted words of bards, and come with niceties like copyright and trademark attached.

And where those things exist, so exist also the corporations and the lawyers. It would be those entities rather than Tolkien or even any of his descendants who would control how his greatest literary work was adapted to screens large, small, and in between. Because far more people in this modern age of ours play games and watch movies than read books of any stripe — much less daunting doorstops like The Lord of the Rings trilogy — this meant that Middle-earth as most people would come to know it wouldn’t be quite the same land of myth that Tolkien himself had created so laboriously over so many decades in his little tobacco-redolent office. Instead, it would be Big Media’s interpretations and extrapolations therefrom. In the first 48 years of its existence, The Lord of the Rings managed to sell a very impressive 100 million copies in book form. In only the first year of its existence, the first installment of Peter Jackson’s blockbuster film trilogy was seen by 150 million people.

To understand how The Lord of the Rings and its less daunting predecessor The Hobbit were transformed from books authored by a single man into a palimpsest of interpretations, we need to understand how J.R.R. Tolkien lost control of his creations in the first place. And to begin to do that, we need to cast our view back to the years immediately following the trilogy’s first issuance in 1954 and 1955 by George Allen and Unwin, who had already published The Hobbit with considerable success almost twenty years earlier.

During its own early years, The Lord of the Rings didn’t do anywhere near as well as The Hobbit had, but did do far better than its publisher or its author had anticipated. It sold at least 225,000 copies (this and all other sales figures given in this article refer to sales of the trilogy as a whole, not to sales of the individual volumes that made up the trilogy) in its first decade, the vast majority of them in its native Britain, despite being available only in expensive hardcover editions and despite being roundly condemned, when it was noticed at all, by the very intellectual and literary elites that made up its author’s peer group. In the face of their rejection by polite literary society, the books sold mostly to existing fans of fantasy and science fiction, creating some decided incongruities; Tolkien never quite seemed to know how to relate to this less mannered group of readers. In 1957, the trilogy won the only literary prize it would ever be awarded, becoming the last recipient of the brief-lived International Fantasy Award, which belied its hopeful name by being a largely British affair. Tolkien, looking alternately bemused and uncomfortable, accepted the award, shook hands and signed autographs for his fans, smiled for the cameras, and got the hell out of there just as quickly as he could.

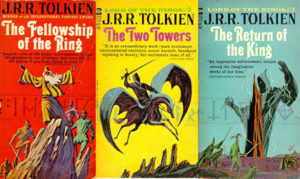

The books’ early success, such as it was, was centered very much in Britain; the trilogy only sold around 25,000 copies in North America during the entirety of its first decade. It enjoyed its first bloom of popularity there only in the latter half of the 1960s, ironically fueled by two developments that its author found thoroughly antithetical. The first was a legally dubious mass-market paperback edition published in the United States by Ace Books in 1965; the second was the burgeoning hippie counterculture.

Donald Wollheim, senior editor at Ace Books, had discovered what he believed to be a legal loophole giving him the right to publish the trilogy, thanks to the failure of Houghton Mifflin, Tolkien’s American hardcover publisher, to properly register their copyright to it in the United States. Never a man prone to hesitation, he declared that Houghton Mifflin’s negligence had effectively left The Lord of the Rings in the public domain, and proceeded to publish a paperback edition without consulting Tolkien or paying him anything at all. Condemned by the resolutely old-fashioned Tolkien for taking the “degenerate” form of the paperback as much as for the royalties he wasn’t paid, the Ace editions nevertheless sold in the hundreds of thousands in a matter of months. Elizabeth Wollheim, daughter of Donald and herself a noted science-fiction and fantasy editor, has characterized the instant of the appearance of the Ace editions of The Lord of the Rings in October of 1965 as the “Big Bang” that led to the modern cottage industry in doorstop fantasy novels. Along with Frank Herbert’s Dune, which appeared the same year, they obliterated almost at a stroke the longstanding tradition in publishing of genre novels as concise works coming in at under 250 pages.

Even as these cheap Ace editions of Tolkien became a touchstone of what would come to be known as nerd culture, they were also seized on by a very different constituency. With the Summer of Love just around the corner, the counterculture came to see in the industrialized armies of Sauron and Saruman the modern American war machine they were protesting, in the pastoral peace of the Shire the life they saw as their naive ideal. The Lord of the Rings became one of the hippie movement’s literary totems, showing up in the songs of Led Zeppelin and Argent, and, as later memorably described by Peter S. Beagle in the most famous introduction to the trilogy ever written, even scrawled on the walls of New York City’s subways (“Frodo lives!”). Beagle’s final sentiments in that piece could stand in very well for the counterculture’s as a whole: “We are raised to honor all the wrong explorers and discoverers — thieves planting flags, murderers carrying crosses. Let us at last praise the colonizers of dreams.”

If Tolkien had been uncertain how to respond to the earnest young science-fiction fans who had started showing up at his doorstep seeking autographs in the late 1950s, he had no shared frame of reference whatsoever with these latest readers. He was a man at odds with his times if ever there was one. On the rare occasions when contemporary events make an appearance in his correspondence, it always reads as jarring. Tolkien comes across a little confused by it all, can’t even get the language quite right. For example, in a letter from 1964, he writes that “in a house three doors away dwells a member of a group of young men who are evidently aiming to turn themselves into a Beatle Group. On days when it falls to his turn to have a practice session the noise is indescribable.” Whatever the merits of the particular musicians in question, one senses that the “noise” of the “Beatle group” music wouldn’t have suited Tolkien one bit in any scenario. And as for Beagle’s crack about “murderers carrying crosses,” it will perhaps suffice to note that his introduction was published only after Tolkien, the devout Catholic, had died. Like the libertarian conservative Robert Heinlein, whose Stranger in a Strange Land became another of the counterculture’s totems, Tolkien suffered the supreme irony of being embraced as a pseudo-prophet by a group whose sociopolitical worldview was almost the diametrical opposite of his own. As the critic Leonard Jackson has noted, it’s decidedly odd that the hippies, who “lived in communes, were anti-racist, were in favour of Marxist revolution and free love” should choose as their favorite “a book about a largely racial war, favouring feudal politics, jam-full of father figures, and entirely devoid of sex.”

Note the pointed reference to these first Ballantine editions of The Lord of the Rings as the “authorized” editions.

To what extent Tolkien was even truly aware of his works’ status with the counterculture is something of an open question, although he certainly must have noticed the effect it had on his royalty checks after the Ace editions were forced off the market, to be replaced by duly authorized Ballantine paperbacks. In the first two years after issuing the paperbacks, Ballantine sold almost 1 million copies of the series in North America alone.

In October of 1969, smack dab in the midst of all this success, Tolkien, now 77 years old and facing the worry of a substantial tax bill in his declining years, made one of the most retrospectively infamous deals in the history of pop culture. He sold the film rights to The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings to the Hollywood studio United Artists for £104,602 and a fixed cut of 7.5 percent of any profits that might result from cinematic adaptations. And along with film rights went “merchandising rights.” Specifically, United Artists was given rights to the “manufacture, sale, and distribution of any and all articles of tangible personal property other than novels, paperbacks, and other printed published matter.” All of these rights were granted “in perpetuity.”

What must have seemed fairly straightforward in 1969 would in decades to come turn into a Gordian Knot involving hundreds of lawyers, all trying to resolve once and for all just what part of Tolkien’s legacy he had retained and what part he had sold. In the media landscape of 1969, the merchandising rights to “tangible personal property” which Tolkien and United Artists had envisioned must have been limited to toys, trinkets, and souvenirs, probably associated with any films United Artists should choose to make based on Tolkien’s books. Should the law therefore limit the contract to its signers’ original intent, or should it be read literally? If the law chose the latter course, Tolkien had unknowingly sold off the videogame rights to his work before videogames even existed in anything but the most nascent form. Or did he really? Should videogames, being at their heart intangible code, really be lumped even by the literalists into the rights sold to United Artists? After all, the contract explicitly reserves “the right to utilize and/or dispose of all rights and/or interests not herein specifically granted” to Tolkien. This question only gets more fraught in our modern age of digital distribution, when games are often sold with no tangible component at all. And then what of tabletop games? They’re quite clearly neither novels nor paperbacks, but they might be, at least in part, “other printed published matter.” What precisely did that phrase mean? The contract doesn’t stipulate. In the absence of any clear pathways through this legal thicket, the history of Tolkien licensing would become that of a series of uneasy truces occasionally erupting into open legal warfare. About the only things that were clear were that Tolkien — soon, his heirs — owned the rights to the original books and that United Artists — soon, the person who bought the contract from them — owned the rights to make movies out of them. Everything else was up for debate. And debated it would be, at mind-numbing length.

It would, however, be some time before the full ramifications of the document Tolkien had signed started to become clear. In the meantime, United Artists began moving forward with a film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings that was to have been placed in the hands of the director and screenwriter John Boorman. Boorman worked on the script for years, during which Tolkien died and his literary estate passed into the hands of his heirs, most notably his third son and self-appointed steward of his legacy Christopher Tolkien. The final draft of Boorman’s script compressed the entire trilogy into a single 150-minute film, and radically changed it in terms of theme, character, and plot to suit a Hollywood sensibility. For instance, Boorman added the element of sex that was so conspicuously absent from the books, having Frodo and Galadriel engage in a torrid affair after the Fellowship comes to Lothlórien. (Given the disparity in their sizes, one does have to wonder about the logistics, as it were, of such a thing.) But in the end, United Artists opted, probably for the best, not to let Boorman turn his script into a movie. (Many elements from the script would turn up later in Boorman’s Arthurian epic Excalibur.)

Of course, it’s unlikely that literary purity was foremost on United Artists’s minds when they made their decision. As the 1960s had turned into the 1970s and the Woodstock generation had gotten jobs and started families, Tolkien’s works had lost some of their trendy appeal, retaining their iconic status only among fantasy fandom. Still, the books continued to sell well; they would never lose the status they had acquired almost from the moment the Ace editions had been published of being the bedrock of modern fantasy fiction, something everyone with even a casual interest in the genre had to at least attempt to read. Not being terribly easy books, they defeated plenty of these would-be readers, who went off in search of the more accessible, more contemporary-feeling epic-fantasy fare so many publishers were by now happily providing. Yet even among the readers it rebuffed The Lord of the Rings retained the status of an aspirational ideal.

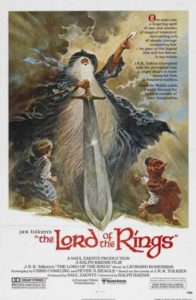

In 1975, a maverick animator named Ralph Bakshi, who had heretofore been best known for Fritz the Cat, the first animated film to earn an X rating, came to United Artists with a proposal to adapt The Lord of the Rings into a trio of animated features that would be relatively inexpensive in comparison to Boorman’s plans for a live-action epic. United Artists didn’t bite, but did signify that they might be amenable to selling the rights they had purchased from Tolkien if Bakshi could put together a few million dollars to make it happen. In December of 1976, following a string of proposals and deals too complicated and imperfectly understood to describe here, a hard-driving music and movie mogul named Saul Zaentz wound up owning the whole package of Tolkien rights that had previously belonged to United Artists. He intended to use his purchase first to let Bakshi make his films and thereafter for whatever other opportunities might happen to come down the road.

Saul Zaentz had first come to prominence back in 1967, when he’d put together a group of investors to buy a struggling little jazz label called Fantasy Records. His first signing as the new president of Fantasy was Creedence Clearwater Revival, a rock group he had already been managing. Whether due to Zaentz’s skill as a talent spotter or sheer dumb luck, it was the sort of signing that makes a music mogul rich for life. Creedence promptly unleashed eleven top-ten singles and five top-ten albums over the course of the next three and a half years, the most concentrated run of hits of any 1960s band this side of the Beatles. And Zaentz got his fair share of all that filthy lucre — more than his fair share, his charges eventually came to believe. When the band fell apart in 1972, much of the cause was infighting over matters of business. The other members came to blame Creedence’s lead singer and principal songwriter John Fogerty for convincing them to sign a terrible contract with Zaentz that gave away rights to their songs to him for… well, in perpetuity, actually. And as for Fogerty, he of course blamed Zaentz for all the trouble. Decades of legal back and forth followed the breakup. At one point, Zaentz sued Fogerty on the novel legal theory of “self-plagiarization”: the songs Fogerty was now writing as a solo artist, went the brief, were too similar to the ones he used to write for Creedence, all of whose copyrights Zaentz owned. While his lawyers pleaded his case in court, Fogerty vented his rage via songs like “Zanz Kant Danz,” the story of a pig who, indeed, can’t dance, but will happily “steal your money.”

I trust that this story gives a sufficient impression of just what a ruthless, litigious man now owned adaptation rights to the work of our recently deceased old Oxford don. But whatever else you could say about Saul Zaentz, he did know how to get things done. He secured financing for the first installment of Bakshi’s animated Lord of the Rings, albeit on the condition that he cut the planned three-film series down to two. Relying heavily on rotoscoping to give his cartoon figures an uncannily naturalistic look, Bakshi finished the film for release in November of 1978. Regarded as something of a cult classic among certain sectors of Tolkien fandom today, in its own day the film was greeted with mixed to poor reviews. The financial picture is equally muddled. While it’s been claimed, including by Bakshi himself, that the movie was a solid success, earning some $30 million on a budget of a little over $4 million, the fact remains that Zaentz was unable to secure funding for the sequel, leaving poor Frodo, Sam, and Gollum forever in limbo en route to Mount Doom. It is, needless to say, difficult to reconcile a successful first film with this refusal to back a second. But regardless of the financial particulars, The Lord of the Rings wouldn’t make it back to the big screen for more than twenty years, until the enormous post-millennial Peter Jackson productions that well and truly, once and for all, broke Middle-earth into the mainstream.

Yet, although the Bakshi adaptation was the only Tolkien film to play in theaters during this period, it wasn’t actually the only Tolkien film on offer. In November of 1977, a year before the Bakshi Lord of the Rings made its bow, a decidedly less ambitious animated version of The Hobbit had played on American television. The force behind it was Rankin/Bass Productions, who had previously been known in television broadcasting for holiday specials such as Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Their take on Tolkien was authorized not by Saul Zaentz but by the Tolkien estate. Being shot on video rather than film and then broadcast rather than shown in theaters, the Rankin/Bass Hobbit was not, legally speaking, a “movie” under the terms of the 1969 contract. Nor was it a “tangible” product, thus making it fair game for the Tolkien estate to authorize without involving Zaentz. That, anyway, was the legal theory under which the estate was operating. They even authorized a sequel to the Rankin/Bass Hobbit in 1980, which rather oddly took the form of an adaptation of The Return of the King, the last book of The Lord of the Rings. A precedent of dueling licenses, authorizing different versions of what to casual eyes at least often seemed to be the very same things, was thus established.

But these flirtations with mainstream visibility came to an end along with the end of the 1970s. After the Ralph Bakshi and Rankin/Bass productions had all had their moments in the sun, The Lord of the Rings was cast back into its nerdy ghetto, where it remained more iconic than ever. Yet the times were changing in some very important ways. From the moment he had clear ownership of the rights Tolkien had once sold to United Artists, Saul Zaentz had taken to interpreting their compass in the broadest possible way, and had begun sending his lawyers after any real or alleged infringers who grew large enough to come to his attention. This marked a dramatic change from the earliest days of Tolkien fandom, when no one had taken any apparent notice of fannish appropriations of Middle-earth, to such an extent that fans had come to think of all use of Tolkien’s works as fair use. In that spirit, in 1975 a tiny game publisher called TSR, incubator of an inchoate revolution called Dungeons & Dragons, had started selling a non-Dungeons & Dragons strategy game called Battle of the Five Armies that was based on the climax of The Hobbit. In late 1977, Zaentz sent them a cease-and-desist letter demanding that the game be immediately taken off the market. And, far more significantly in the long run, he also demanded that all Tolkien references be excised from Dungeons & Dragons. It wasn’t really clear that Zaentz ought to have standing to sue, given that Battle of the Five Armies and especially Dungeons & Dragons consisted of so much of the “printed published matter” that was supposedly reserved to the Tolkien estate. But, hard charger that he was, Zaentz wasn’t about to let such niceties stop him. He was establishing legal precedent, and thereby cementing his position for the future.

The question of just how much influence Tolkien had on Dungeons & Dragons has been long obscured by this specter of legal action, which gave everyone on the TSR side ample reason to be less than entirely forthcoming. That said, certain elements of Dungeons & Dragons — most obviously the “hobbit” character class found in the original game — undeniably walked straight off the pages of Tolkien and into those of Gary Gygax’s rule books. At the same time, though, the mechanics of Dungeons & Dragons had, as Gygax always strenuously asserted, much more to do with the pulpier fantasy stories of Jack Vance and Robert E. Howard than they did with Tolkien. Ditto the game’s default personality, which hewed more to the “a group of adventurers meet in a bar and head out to bash monsters and collect treasure” modus operandi of the pulps than it did to Tolkien’s deeply serious, deeply moralistic, deeply tragic universe. You could play a more “serious” game of Dungeons & Dragons even in the early days, and some presumably did, but you had to bend the mechanics to make them fit. The more light-hearted tone of The Hobbit might seem better suited, but wound up being a bit too light-hearted, almost as much fairy tale as red-blooded adventure fiction. Some of the book’s episodes, like Bilbo and the dwarves’ antics with the trolls near the beginning of the story, verge on cartoon slapstick, with none of the swashbuckling swagger of Dungeons & Dragons. I love it dearly — far more, truth be told, than I love The Lord of the Rings — but not for nothing was The Hobbit conceived and marketed as a children’s novel.

Gygax’s most detailed description of the influence of Tolkien on Dungeons & Dragons appeared in the March 1985 issue of Dragon magazine. There he explicated the dirty little secret of adapting Tolkien to gaming: that the former just wasn’t all that well-suited for the latter without lots of sweeping changes.

Considered in the light of fantasy action adventure, Tolkien is not dynamic. Gandalf is quite ineffectual, plying a sword at times and casting spells which are quite low-powered (in terms of the D&D game). Obviously, neither he nor his magic had any influence on the games. The Professor drops Tom Bombadil, my personal favorite, like the proverbial hot potato; had he been allowed to enter the action of the books, no fuzzy-footed manling would have needed to undergo the trials and tribulations of the quest to destroy the Ring. Unfortunately, no character of Bombadil’s power can enter the games either — for the selfsame reasons! The wicked Sauron is poorly developed, virtually depersonalized, and at the end blows away in a cloud of evil smoke… poof! Nothing usable there. The mighty Ring is nothing more than a standard ring of invisibility, found in the myths and legends of most cultures (albeit with a nasty curse upon it). No influence here, either…

What Gygax gestures toward here but doesn’t quite touch is that The Lord of the Rings is at bottom a spiritual if not overtly religious tale, Middle-earth a land of ineffable unknowables. It’s impossible to translate that ineffability into the mechanistic system of causes and effects required by a game like Dungeons & Dragons. For all that Gygax is so obviously missing the point of Tolkien’s work in the extract above — rather hilariously so, actually — it’s also true that no Dungeon Master could attempt something like, say, Gandalf’s transformation from Gandalf the Grey to Gandalf the White without facing a justifiable mutiny from the players. Games — at least this kind of game — demand knowable universes.

Gygax claimed that Tolkien was ultimately far more important to the game’s commercial trajectory than he was to its rules. He noted, accurately, that the trilogy’s popularity from 1965 on had created an appetite for more fantasy, in the form of both books and things that weren’t quite books. It was largely out of a desire to ride this bandwagon, Gygax claimed, that Chainmail, the proto-Dungeons & Dragons which TSR released in 1971, promised players right there on the cover that they could use it to “refight the epic struggles related by J.R.R. Tolkien, Robert E. Howard, and other fantasy writers.” Gygax said that “the seeming parallels and inspirations are actually the results of a studied effort to capitalize on the then-current ‘craze’ for Tolkien’s literature.” Questionable though it is how “studied” his efforts really were in this respect, it does seem fairly clear that the biggest leg-up Tolkien gave to Gygax and his early design partner Dave Arneson was in giving so many potential players a taste for epic fantasy in the first place.

At any rate, we can say for certain that, beyond prompting a grudge in Gary Gygax against all things Tolkien — which, like most Gygaxian grudges, would last the rest of its holder’s life — Zaentz’s legal threat had a relatively modest effect on the game of Dungeons & Dragons. Hobbits were hastily renamed “halflings,” a handful of other references were scrubbed away or obfuscated, and life went on.

More importantly for Zaentz, the case against TSR and a few other even smaller tabletop-game publishers had now established the precedent that this field was within his licensing purview. In 1982, Tolkien Enterprises, the umbrella corporation Zaentz had created to manage his portfolio, authorized a three-employee publisher called Iron Crown Enterprises, heretofore known for the would-be Dungeons & Dragons competitor Rolemaster, to adapt their system to Middle-earth. Having won the license by simple virtue of being the first publisher to work up the guts to ask for it, Iron Crown went on to create Middle-earth Role Playing. The system rather ran afoul of the problem we’ve just been discussing: that, inspiring though so many found the setting in the broad strokes, the mechanics — or perhaps lack thereof — of Middle-earth just didn’t lend themselves all that well to a game. Unsurprisingly in light of this, Middle-earth Role Playing acquired a reputation as a “game” that was more fun to read, in the form of its many lengthy and lovingly detailed supplements exploring the various corners of Middle-earth, than it was to actually play; some wags took to referring to the line as a whole as Encyclopedia Middle-earthia. Nevertheless, it lasted more than fifteen years, was translated into twelve languages, and sold over 250,000 copies in English alone, thereby becoming one of the most successful tabletop RPGs ever not named Dungeons & Dragons.

But by no means was it all smooth sailing for Iron Crown. During the game’s early years, which were also its most popular, they were very nearly undone by an episode that serves to illustrate just how dangerously confusing the world of Tolkien licensing could become. In 1985, Iron Crown decided to jump on the gamebook bandwagon with a line of paperbacks they initially called Tolkien Quest, but quickly renamed to Middle-earth Quest to tie it more closely to their extant tabletop RPG. Their take on the gamebook was very baroque in comparison to the likes of Choose Your Own Adventure or even Fighting Fantasy; the rules for “reading” their books took up thirty pages on their own, and some of the books included hex maps for plotting your movements around the world, thus rather blurring the line between gamebook and, well, game. Demian Katz, who operates the definitive Internet site devoted to gamebooks, calls the Middle-earth Quest line “among the most complex gamebooks ever published,” and he of all people certainly ought to know. Whether despite their complexity or because of it, the first three volumes in the line were fairly successful for Iron Crown — and then the legal troubles started.

The Tolkien estate decided that Iron Crown had crossed a line with their gamebooks, encroaching on the literary rights to Tolkien which belonged to them. Whether the gamebooks truly were more book or game is an interesting philosophical question to ponder — particularly so given that they were such unusually crunchy iterations on the gamebook concept. Questions of philosophical taxonomy aside, though, they certainly were “printed published matter” that looked for all the world like everyday books. Tolkien Enterprises wasn’t willing to involve themselves in a protracted legal showdown over something as low-stakes as a line of gamebooks. Iron Crown would be on their own in this battle, should they choose to wage it. Deciding the potential rewards weren’t worth the risks of trying to convince a judge who probably wouldn’t know Dungeons & Dragons from Maze & Monsters that these things which looked like conventional paperback books were actually something quite different, Iron Crown pulled the line off the market and destroyed all copies as part of a settlement agreement. The episode may have cost them as much as $2.5 million. A few years later, the ever dogged Iron Crown would attempt to resuscitate the line after negotiating a proper license with the Tolkien estate — no mean feat in itself; Christopher Tolkien in particular is famously protective of that portion of his father’s legacy which is his to protect — but by then the commercial moment of the gamebook in general had passed. The whole debacle would continue to haunt Iron Crown for a long, long time. In 2000, when they filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, they would state that the debt they had been carrying for almost fifteen years from the original gamebook settlement was a big part of the reason.

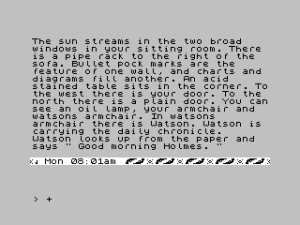

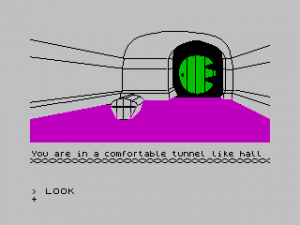

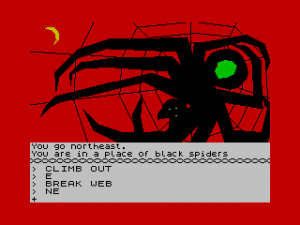

By that point, the commercial heyday of the tabletop RPG was also long past. Indeed, already by the time that Iron Crown and Tolkien Enterprises had inked their first licensing deal back in 1982 computer-based fantasies, in the form of games like Zork, Ultima and Wizardry, were threatening to eclipse the tabletop varieties that had done so much to inspire them. Here, perhaps more so even than in tabletop RPGs, the influence of Tolkien was pervasive. Designers of early computer games often appropriated Middle-earth wholesale, writing what amounted to interactive Tolkien fan fiction. The British text-adventure house Level 9, for example, first made their name with Colossal Adventure, a re-implementation of Will Crowther and Don Woods’s original Adventure with a Middle-earth coda tacked onto the end, thus managing the neat trick of extensively plagiarizing two different works in a single game. There followed two more Level 9 games set in Middle-earth, completing what they were soon proudly advertising, in either ignorance or defiance of the concept of copyright, as their Middle-earth Trilogy.

But the most famous constant devotee and occasional plagiarist of Tolkien among the early computer-game designers was undoubtedly Richard Garriott, who had discovered The Lord of the Rings and Dungeons & Dragons, the two influences destined more than any other to shape the course of his life, within six months of one another during his teenage years. Garriott called his first published game Akalabeth, after Tolkien’s Akallabêth, the name of a chapter in The Silmarillion, a posthumously published book of Middle-earth legends. The word means “downfall” in one of Tolkien’s invented languages, but Garriott chose it simply because he thought it sounded cool; his game otherwise had little to no explicit connection to Middle-earth. Regardless, the computer-game industry wouldn’t remain small enough that folks could get away with this sort of thing for very long. Akalabeth soon fell out of print, superseded by Garriott’s more complex series of Ultima games that followed it, while Level 9 was compelled to scrub the erstwhile Middle-earth Trilogy free of Tolkien and re-release it as the Jewels of Darkness Trilogy.

In the long-run, the influence of Tolkien on digital games would prove subtler but also even more pervasive than these earliest forays into blatant plagiarism would imply. Richard Garriott may have dropped the Tolkien nomenclature from his subsequent games, but he remained thoroughly inspired by the example of Tolkien, that ultimate fantasy world-builder, when he built the world of Britannia for his Ultima series. Of course, there were obvious qualitative differences between Middle-earth and Britannia. How could there not be? One was the creation of an erudite Oxford don, steeped in a lifetime worth of study of classical and Medieval literature; the other was the creation of a self-described non-reader barely out of high school. Nowhere is the difference starker than in the area of language, Tolkien’s first love. Tolkien invented entire languages from scratch, complete with grammars and pronunciation charts; Garriott substituted a rune for each letter in the English alphabet and seemed to believe he had done something equivalent. Garriott’s clumsy mishandling of Elizabethan English, meanwhile, all “thees” and “thous” in places where the formal “you” should be used, is enough to make any philologist roll over in his grave. But his heart was in the right place, and despite its creator’s limitations Britannia did take on a life of its own over the course of many Ultima iterations. If there is a parallel in computer gaming to what The Lord of the Rings and Middle-earth came to mean to fantasy literature, it must be Ultima and its world of Britannia.

In addition to the unlicensed knock-offs that were gradually driven off the market during the early 1980s and the more abstracted homages that replaced them, there was also a third category of Tolkien-derived computer games: that of licensed products. The first and only such licensee during the 1980s was Melbourne House, a book publisher turned game maker located in far-off Melbourne, Australia. Whether out of calculation or happenstance, Melbourne House approached the Tolkien estate rather than Tolkien Enterprises in 1982 to ask for a license. They were duly granted the right to make a text-adventure adaptation of The Hobbit, under certain conditions, very much in character for Christopher Tolkien, intended to ensure respect for The Hobbit‘s status as a literary work; most notably, they would be required to include a paperback copy of the novel with the game. In a decision he would later come to regret, Saul Zaentz elected to cede this ground to the Tolkien estate without a fight, apparently deeming a computer game intangible enough to be dangerous to quibble over. Another uneasy, tacit, yet surprisingly enduring precedent was thus set: Tolkien Enterprises would have control of Tolkien tabletop games, while the Tolkien estate would have control of Tolkien videogames. Zaentz’s cause for regret would come as he watched the digital-gaming market explode into tens and then hundreds of times the size of the tabletop market.

In fact, that first adaptation of The Hobbit played a role in that very process. The game became a sensation in Europe — playing it became a rite of passage for a generation of gamers there — and a substantial hit in the United States as well. It went on to become almost certainly the best-selling single text adventure ever made, with worldwide sales that may have exceeded half a million units. I’ve written at length about the Hobbit text adventure earlier, so I’ll refer you back to that article rather than describe its bold innovations and weird charm here. Otherwise, suffice to say that The Hobbit‘s success proved, if anyone was doubting, that licenses in computer games worked in commercial terms, no matter how much some might carp about the lack of originality they represented.

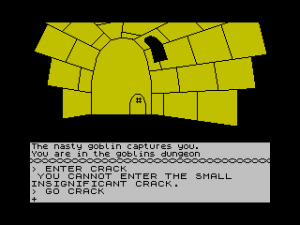

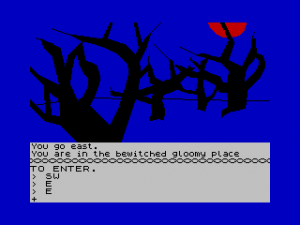

Still, Melbourne House appears to have had some trepidation about tackling the greater challenge of adapting The Lord of the Rings to the computer. The reasons are understandable: the simple quest narrative that was The Hobbit — the book is actually subtitled There and Back Again — read like a veritable blueprint for a text adventure, while the epic tale of spiritual, military, and political struggle that was The Lord of the Rings represented, to say the least, a more substantial challenge for its would-be adapters. Melbourne House’s first anointed successor to The Hobbit‘s thus became Sherlock, a text adventure based on another literary property entirely. They didn’t finally return to Middle-earth until 1986, four years after The Hobbit, when they made The Fellowship of the Ring into a text adventure. Superficially, the new game played much like The Hobbit, but much of the charm was gone, with quirks that had seemed delightful in the earlier game now just seeming annoying. Even had The Fellowship of the Ring been a better game, by 1986 it was getting late in the day for text adventures — even text adventures like this one with illustrations. Reviews were lukewarm at best. Nevertheless, Melbourne House kept doggedly at the task of completing the story of Frodo and the One Ring, releasing The Shadows of Mordor in 1987 and The Crack of Doom in 1989. All of these games went largely unloved in their day, and remain so in our own.

In a belated attempt to address the formal mismatch between the epic narrative of The Lord of the Rings and the granular approach of the text adventure, Melbourne House released War in Middle-earth in 1988. Partially designed by Mike Singleton, and drawing obvious inspiration from his older classic The Lords of Midnight, it was a strategy game which let the player refight the entirety of the War of the Ring, on the level of both armies and individual heroes. The Lords of Midnight had been largely inspired by Singleton’s desire to capture the sweep and grandeur of The Lord of the Rings in a game, so in a sense this new project had him coming full circle. But, just as Melbourne House’s Lord of the Rings text adventures had lacked the weird fascination of The Hobbit, War in Middle-earth failed to rise to the heights of The Lords of Midnight, despite enjoying the official license the latter had lacked.

As the 1980s came to a close, then, the Tolkien license was beginning to rival the similarly demographically perfect Star Trek license for the title of the most misused and/or underused — take your pick — in computer gaming. Tolkien Enterprises, normally the more commercially savvy and aggressive of the two Tolkien licensers, had ceded that market to the Tolkien estate, who seemed content to let Melbourne House doddle along with an underwhelming and little-noticed game every year or two. At this point, though, another computer-game developer would pick up the mantle from Melbourne House and see if they could manage to do something less underwhelming with it. We’ll continue with that story next time.

Before we get to that, though, we might take a moment to think about how different things might have been had the copyrights to Tolkien’s works been allowed to expire with their creator. There is some evidence that Tolkien himself held to this as the fairest course. In the late 1950s, in a letter to one of the first people to approach him about making a movie out of The Lord of the Rings, he expressed his wish that any movie made during his lifetime not deviate too far from the books, citing as an example of what he didn’t want to see the 1950 movie of H. Rider Haggard’s Victorian adventure novel King’s Solomon’s Mines and the many liberties it took with its source material. “I am not Rider Haggard,” he wrote. “I am not comparing myself with that master of Romance, except in this: I am not dead yet. When the film of King’s Solomon’s Mines was made, it had already passed, one might say, into the public property of the imagination. The Lord of Rings is still the vivid concern of a living person, and is nobody’s toy to play with.” Can we read into this an implicit assumption that The Lord of the Rings would become part of “the public property of the imagination” after its own creator’s death? If so, things turned out a little differently than he thought they would. A “property of the imagination” Middle-earth has most certainly become. It’s the “public” part that remains problematic.

(Sources: the books Designers & Dragons Volume 1 and Volume 2 by Shannon Appelcline, Tolkien’s Triumph: The Strange History of The Lord of the Rings by John Lennard, The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood by Kristin Thompson, Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi by John M. Gibson, Playing at the World by Jon Peterson, and Dungeons and Dreamers: The Rise of Computer Game Culture from Geek to Chic by Brad King and John Borland; Dragon Magazine of March 1985; Popular Computing Weekly of December 30 1982; The Times of December 15 2002. Online sources include Janet Brennan Croft’s essay “Three Rings for Hollywood” and The Hollywood Reporter‘s archive of a 2012 court case involving Tolkien’s intellectual property.)