In the novel version of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Arthur C. Clarke discusses the music choices of astronaut David Bowman in the latter stages of his voyage to Saturn aboard the Discovery, after the malfunctioning supercomputer HAL has killed all of his crew mates and left him as alone as any human has ever been, millions of miles from the nearest fellow member of his species. He begins with opera, but soon finds that he can’t bear to hear human voices. So he moves on to the instrumental music of the Romantic composers, but soon finds their emotionalism “oppressive.” At last he finds peace in the cool abstractions of Bach’s architectures in sound.

It’s a passage that always makes me think of Clarke’s own qualities as a writer. You won’t find rich characters in his works, nor any insight whatsoever into that elusive thing known as the Human Condition. When he tries to do that sort of thing, the results are always odd, like something written from the standpoint of an alien who doesn’t quite get the chaotic emotions of humanity. And sometimes it’s kind of creepy. Take our subject for today, Rendezvous with Rama, which postulates a society of the future in which plural marriage is the norm and the crew aboard a spaceship can engage in spirited orgies without it breeding jealousies or having any effect on their group cohesion. Like when reading Heinlein’s libertarian free-love fantasies, this stuff leaves me screaming at the pages that people just aren’t made that way — not to mention that it leaves out virtually everything that’s actually interesting to read about love and sex. Sex to Clarke is all clunky mechanical and chemical interactions. It’s little surprise that he waxes poetic on the “sexual overtones” of spaceship docking in 2010. (“The rugged, compact Russian ship did look positively male when compared with the delicate, slender American one.”)

So, no, you don’t read Clarke for his insights into the psyche. What you do read him for are his Big Ideas, and for a glimpse at the ineffable majesty of the universe in all its unfathomable immensity and improbable orderliness. Published in 1973 when Clarke was at the peak of his powers and popularity in the wake of the 2001 film and novel, Rendezvous with Rama shines despite the aforementioned embarrassing attempts at personalizing its rather abstract story. It shines so brightly, in fact, that’s it’s arguably the archetypical Clarke novel, the one to read if you want to appreciate who he was and why he is important through a single book.

Rama tells the story of an object which enters the solar system from interstellar space in the year 2131. At first observers assume the object, which they christen Rama, to be just another asteroid — albeit a large one, with a diameter of some 40 kilometers. When a probe is launched to take pictures, however, the truth is immediately obvious: Rama was made rather than formed. It’s a spaceship of some sort, humankind’s first visitor from the stars. It’s hastily determined that exactly one spacecraft, the Endeavor, can make rendezvous before Rama slingshots around the Sun and back out into the depths of interstellar space. The bulk of the novel tells of the Endeavor‘s crew’s methodical exploration of Rama’s interior. There are a few emergencies to spice things up, but mostly Clarke is content to revel in the sense of wonder of the occasion and the unknowable mystery that is Rama itself, which operates with all the austere and remorseless precision of a Bach fugue. The Endeavor is forced to leave to avoid being burned up as Rama nears perihelion with the Sun. As Rama does so it siphons energy from the Sun itself by a mysterious process. And then it’s gone, leaving behind more questions than it answered. Rama, it seems, never had any interest in Earth or its inhabitants; our solar system was merely a handy gas station on the road to who knows where.

Clarke’s refusal to do more than nick the outer layer of the onion of mysteries that is Rama is, as a thousand reviewers before me have already commented, kind of infuriating. Yet it’s also crucial to the veneer of believability that makes Rama’s wonders all the more wondrous for us the readers. Why should we expect to understand an alien culture advanced enough to build something like Rama after a few weeks of poking around inside a single artifact? The unsolved mysteries are actually key to a sense of awe that can only be diminished by reading the series of ill-advised sequels which Clarke farmed out to Gentry Lee in his latter years, which give us the answers we thought we wanted and in the process turn the story into just another mediocre space opera.

In addition to a sense of awe, Rendezvous with Rama also leaves us with one humdinger of a setup for an adventure game. Rama‘s plot, such as it is, of exploring a conveniently deserted spaceship and trying to puzzle out how things work reads like it was written with the medium in mind. It thus served as ready inspiration for such early adventure games as Infocom’s Starcross. And thus when Byron Preiss started looking for books to adapt to interactive fiction Rendezvous with Rama was about the most obvious candidate imaginable, especially because Preiss already had an established professional and personal relationship with Clarke; Preiss had recently produced The Sentinel, a collection of nine vintage Clarke short stories, for Berkley Book’s Masterworks of Science Fiction and Fantasy series, and was currently helping him with an autobiography that would never actually emerge. The contract was quickly signed.

Like Fahrenheit 451 and Dragonworld, the other two of the initial group of Telarium games that originated with the imprint, Rendezvous with Rama was created by a new shell company Preiss and Spinnaker founded just for the purpose: Byron Preiss Video Productions. Spinnaker’s Chief Technology Officer, Dick Bratt, masterminded an ambitious and expensive cross-platform adventure-game engine called SAS, the Spinnaker Adventure System. His job was made more challenging by the fact that he needed to support not just text but also graphics, sounds, even embedded action games. Given Preiss’s history as a publisher of graphic novels and lavishly illustrated coffee-table books, this all-plus-the-kitchen-sink approach to computerized storytelling was a virtual inevitability. Bill Bowman, one of Spinnaker’s founding partners, described SAS in some detail in a Harvard Business School case study:

It has been an important investment, and gives us a competitive advantage nobody else has. It cost well over $1 million, but it enables us to take a script from an author, add some art work, and a secretary can translate it into SAL (Spinnaker Adventure Language) that we created here. It is a very complex computer program and a sophisticated graphics tool. The result is that we put the new game on the machine once, and automatically get versions for each of the different microcomputers we support. This cuts the development costs dramatically, because normally you have to rewrite the program for each version for a different computer. Another important advantage is that we have all versions ready for sale at the same time, and we can profit from advertising, and not lose sales. SAL is a part of SAS (Spinnaker Adventure System). The second part of SAS is a graphics tool, that takes a normal picture on paper and prepares programs for all the different computers that display it. We have something similar for music: our musician plays some music in a special organlike machine, and in less than an hour we have the computer code that will play that music, optimized for each microcomputer. Another very important saying is that we have to “play test” the programs only once. Testing is a very important cost; it can take between 200 and 400 hours to test all the options that one of these programs offers. We would have to do it for each version of the same program if they were programmed independently, as almost everybody else in the industry does. Thanks to the system, our production costs are now about a third of what they were one year ago. It is an enormous asset for us. Two or three companies, at most, have something similar for text, but nobody has anything like it for graphics and music in the whole industry, and these features are becoming more and more important.

Having spent some time dissecting the Telarium games, I feel pretty confident in saying how SAL works. All of the basic logic for the game is compiled to native code for the target platform, of which there were only an eventual four: the Commodore 64, Apple II, IBM PC, and Atari ST. This kernel of perhaps 30 to 35 K remains in memory all the time. All of the assets it needs, including the actual text that is displayed as well as pictures and music, are stored on the games’ multiple disk sides, to be swapped into memory as needed. (If the assets needed are not on the disk currently in the drive, the kernel simply puts up a prompt to ask for the one it needs.) Action games can be swapped in in place of the usual adventure kernel, which they simply reload when done. All of this could add up to quite a lot of data by the standards of the time. Telarium games spill across four or five disk sides on the Apple II and Commodore 64, a fact Spinnaker happily trumpeted in their advertising.

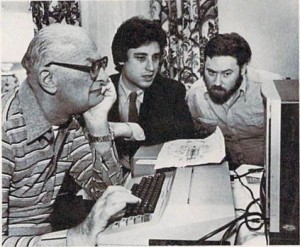

The team that worked on Rendezvous with Rama included programmer Michael P. Meyer and illustrator Robert Strong, along with writer and designer Ronald Martinez, one of Preiss’s regular stable of writers who had cut his teeth on interactivity via a couple of volumes in the Be an Interplanetary Spy series of interactive children’s books. Arthur C. Clarke’s own participation was, at best, limited. He lived, as he had already for almost thirty years, in Sri Lanka, and traveled so reluctantly that when he agreed to host a British television series on unusual science phenomena he required that the film crew come to him. The Telarium folks met him in person just twice during their work on the game, when he set aside afternoons during his occasional trips Stateside for consultations on the upcoming film version of 2010 to chat with them and — one senses most importantly — pose for some press photos with them. (Had it not been for 2010, it’s questionable whether they would have met at all.) The rest of the time they communicated with him via telephone and, most commonly, email, thanks to a satellite linkup Clarke (who famously first proposed the idea of the geosynchronous communications satellite in 1945) had installed in his home in Sri Lanka. Martinez says they would “run things by him,” but admits that it was “never really clear how much he was understanding or how much he was really digging into it.” Clarke’s biggest role was to pose for those publicity photos and to furnish a suitable quote written (or ghost-written) just for the back of the box.

So, Martinez and team were largely left alone to do with Rendezvous with Rama what they would. What that should be was by no means entirely clear. The notion of bookware sounded great when first broached, but as soon as one started to really think about it some problematic aspects started to surface. Trying to slavishly recreate the plot of a book as a game was a technical impossibility. Interactive-fiction systems simply couldn’t handle the complexity of even the most simplistic of novels. Even Infocom’s games, the class of the industry, could manage only the sketchiest of plots to motivate their exploration and puzzle solving; suffice to say that none of their games would have made good books. No one had a good solution for the combinatorial explosion of possibilities that would be touched off as soon as the player deviated from the plot, yet neither was there much point in just forcing the player to recreate the events of the novel. And how to make the game interesting and challenging to players, many of whom were presumably there because they had already read the book on which the game was based and thus knew everything that happened in it? Other Telarium games tried to work around these questions in a variety of ways. Rendezvous with Rama, however, didn’t really bother; it’s the only of the first batch of games to settle for just retelling the same essential story in radically simplified fashion, with the obligatory excising of all reference to the Endeavor‘s crew’s sex lives and other modest content changes apparently more motivated by the need to not offend than anything else. (The most appreciated of these involves the simps, creepy genetically modified monkeys that the crew of the Endeavor use essentially as slaves for all menial tasks in the book. In the game, the simps thankfully become androids.)

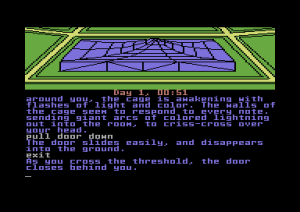

In Telarium’s defense, the novel is, as already noted, almost absurdly amenable to adaptation as an adventure game. Still, it’s difficult indeed to excuse the lukewarm nature of the whole enterprise. Rama the novel is far from intricately plotted, but there is a dynamism to its version of Rama the spacecraft, which slowly comes to life as it draws nearer to the Sun: lights come on, strange mechanisms begin to hum with energy, the atmosphere warms, and, most fabulous of all, semi-organic automatons start to scuttle about for reasons that can only be surmised. None of these surprises unfold in the game. Rama is simply another static environment to be explored, of the sort we’d already seen in a thousand adventure games before. The limitations of the SAL engine may explain such failings, but it doesn’t excuse them. Infocom had been creating virtual worlds that evolved on large scales during play for years by the time of this game’s release.

Nor does Martinez seem all that enthused to tell us about said static world. Clarke is no poet, but his descriptions of Rama’s interior are suitably awe-inspiring. Here’s how Captain Norton of the Endeavor glimpses the panorama for the first time:

With all his strength, he threw the little cylinder straight upward — or outward — and started to count seconds as it dwindled along the beam. Before he had reached the quarter minute, it was out of sight; when he had got to a hundred, he shielded his eyes and aimed the camera. He had always been good at estimating time; he was only two seconds off when the world exploded with light. And this time there was no cause for disappointment. Even the millions of candle power of the flare could not light up the whole of this enormous cavity, but he could see enough to grasp its plan and appreciate its titanic scale. He was at one end of a hollow cylinder at least ten kilometers wide, and of indefinite length. From his viewpoint at the central axis, he could see such a mass of detail on the curving walls surrounding him that his mind could not absorb more than a minute fraction of it. He was looking at the landscape of an entire world by a single flash of lightning, and he tried by a deliberate effort of will to freeze the image in his mind.

All around him, the terraced slopes of crater rose up until they merged into the solid wall that rimmed the sky. No— that impression was false; he must discard the instincts both of Earth and of space, and reorientate himself to a new system of co-ordinates.

The description then continues for several more paragraphs.

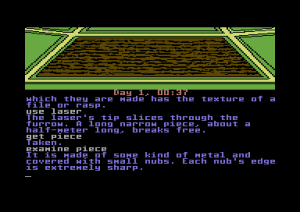

When we step inside the vast cylindrical cavity of Rama for the first time in the game, Martinez gives us this:

You are at RAMA’s somewhat flattened, northern hub. The floor around the hub curves up gradually to become RAMA’s inner walls. Radiating from the hub, 120 degrees apart, are three stairway-like structures. Each appears to be several kilometers long. Due to its configuration, it seems as though you are standing upright on the hub, with the passageway from the long corridor going down in relation to your current position.

There’s no sense of the momentousness of the occasion; Martinez manages to make the most wondrous archaeological expedition in human history seem boring. Yes, technical limitations made it impossible to indulge in the sort of long passages that Clarke could employ, but Dave Lebling did a better job in Starcross in the face of similar restrictions, and Pete Austin did a still better job in Snowball. And the pictures, which are largely all done in the same palette and all but indistinguishable from one another, show no more enthusiasm for their subjects.

All of this is particularly baffling in light of Telarium’s expressed plans to get beyond adventure games as static puzzle boxes. Yet that’s all that Rendezvous with Rama is. If I may speak anachronistically, it’s downright Myst-like, just a static, empty landscape with strange machines to manipulate and puzzle out. Character interaction is limited to the occasional message over your helmet speaker from one of your crewmates, and the ability to occasionally use them as a hint system by asking them to ADVISE.

Worse, it’s not a particularly good puzzle box, a huge disappointment considering that the scenario is positively teeming with puzzle possibilities (as a later Myst-like graphic game, Rama, would amply demonstrate). The vast interior of Rama is implemented as hundreds of individual, mostly empty rooms to be tediously trod through and mapped in the hopes of finding something, anything that you can actually do. When you find them, the puzzles themselves are sometimes interesting, but too often push the limits of the world model past the breaking point. That’s apparently not that hard to do; even some of the “puzzles” described in the novel that were seemingly lifted right out of an adventure game had to be simplified to make them work in this adventure game. Often you have to read Martinez’s mind along with his text to see exactly what he is seeing, as the text fails to clearly set the scene (usually a sign of a lack of testing). Take this description of the wall of a structure:

The rectangular building is about 20 meters tall and 10 wide. Its surface is like polished enamel. A single post rises from the roof, and there are small indentations in the wall you are facing.

I spent quite some fiddling with the indentations, sure they must be some mechanism for opening a door. But actually they’re handholds, for climbing. The text fails to convey that they go all the way up the wall. It’s a clever puzzle, as far as it goes. (It’s not as trivial as just climbing the wall; the handholds are too small — for you). But it’s ruined by the failure to, you know, clearly tell me what I’m actually seeing. The parser, which in general is not horrible but definitely more limited than Infocom’s, also makes puzzle solving harder by its lack of feedback. Virtually any invalid input is greeted with the blasé non sequitur “You reconsider your words.” And absolutely no attention is given to partially correct actions that could serve as hints, not to mention the Easter eggs that make Infocom games like Sorcerer such a delight. Nope, just “You reconsider your words” over and over again.

A purposelessness infects all of your wanderings. It’s clear in the abstract what your mission should be — to explore this huge spaceship — but it’s not clear what the game expects from you in that context. There is no scoring system or other way of measuring your progress. There is a timer which does represent one of the game’s few innovations. It counts down in real time, forerunner of quite a number of (mostly underwhelming) experiments with real-time elements that interactive-fiction makers would indulge in over the next several years. Still, even this innovation is undermined by the fact that you’re never told exactly how much time you have. In fact, you have so much time that it’s hard to imagine it ever becoming a real problem. Rama‘s other notable innovation, a couple of shoehorned action games, is problematic in conception and horrid in execution. Both are so bad that Telarium ripped them out of later versions of Rama out of sheer embarrassment.

It eventually emerges that you don’t have enough fuel to escape; you must find a source on Rama itself. This additional source of drama was not in the book, and is kind of absurd from a fictional standpoint, as it means that you’ve effectively been sent on a suicide mission. (Who would have imagined that fuel would conveniently be available on Rama?) But, hey, at least it’s motivation of a sort. If you jump through a truly improbable series of puzzly hoops you can eventually reach a much vaunted “new ending” to the story, in which you learn that — oh, no, not this trope again! — Rama is actually an elaborate intelligence test constructed by distant aliens to measure humanity’s worthiness for future contact. Not only does this idea rip off Starcross (where it was equally unsatisfying), but it also cuts off at the knees the central theme of Clarke’s novel that we humans just aren’t that important in the grand scheme of things. For a game that was supposed to be the herald of a new era of interactive fiction of serious literary merit, Rama‘s shabby, ham-handed take on the novel that inspired it is appalling.

So, no, Rendezvous with Rama is not a very good game. Even the supremely uncritical computer press of 1984 couldn’t bear to give it more than neutral reviews; “nothing special” wrote adventure superfan Shay Addams in Commodore Power Play in a typical example. Those who had been hostile to the entire idea of Telarium from the beginning must have been nodding along happily, having had all of their prejudices and low expectations justified. Luckily for us if somewhat more disconcertingly for them, most of Telarium’s other games would have a bit more to recommend them.

Perhaps the oddest outcome of Telarium’s Rendezvous with Rama was the subsequent career of the man responsible for all that dull text, Ronald Martinez. Whatever his failings on this project, Martinez became fascinated with the idea of interactive fiction, and determined to do it better than he had in this game. He learned how to program so as to work on a new suite of interactive-fiction technology, and eventually founded Trans Fiction Systems, an interactive-fiction development studio of his own whose parser was one of the few that could legitimately rival Infocom’s. We may just be running into him and his works again on this blog. When and if we do, I should have more positive things to say about both.

The Telarium story should also get more inspiring from here. In the meantime, the masochists and historians among you may want to download the Commodore 64 version of Rendezvous with Rama for yourselves.

(The same references I used for my introduction to Telarium and bookware mostly apply here. Jason Scott’s interview with Ron Martinez for Get Lamp was particularly useful for this article. The photos were taken from an article in the December 1984 Compute!’s Gazette.)