I find that it’s oddly difficult for me to tell the story of Presto Studios, the maker of the Journeyman Project series of cult-classic adventure games, without drawing a lot of parallels and comparisons to Cyan, Inc., the maker of the multi-million-selling mega-hit Myst. This is not only because Presto won the lottery after making their last Journeyman Project game, when Cyan awarded them a contract to make a single-player Myst III while they themselves pursued an online multi-player adventure game that was to be called Uru. It’s also down to other similarities, the same ones that must have made that choice of Presto as a Myst custodian seem like such an obvious one to Cyan.

Both studios were born and bred on the Apple Macintosh in the first blush of excitement over hypertext, CD-ROM, and multimedia, all of which came somewhat earlier to the artsy, freewheeling Mac than they did to the more plebeian, business-oriented MS-DOS and Windows. And both studios saw themselves more as artists’ conclaves than as conventional game-development houses. Four words were to be found in the background of Presto’s logo: “Animation,” “Interactivity,” “Video,” and “Music.” Their “mentality did not include advanced game programming,” as Presto producer Michael Saladino wrote shortly after the company’s final closure. In the early days especially, both Presto and Cyan were happy to leverage off-the-shelf middleware packages in order to string their lovingly sculpted audiovisual assets together into a game. This made them the polar opposite of a house like id Software, for whom Code was the alpha and omega. It’s no surprise that gamers who preferred action to contemplation loved to mock Presto and Cyan for their slow-moving, slideshow-like games.

Said games had in common a first-person perspective on worlds which their players traversed by jumping from static node to static node in a coherent but pre-rendered three-dimensional space. As most of you doubtless know already, these were the hallmarks of the sub-genre that came to be known as “Myst clones.” As we’re about to see, though, the resemblance of The Journeyman Project to Myst had more to do with parallel evolution than rank imitation.

And there’s another, more subjective point that differentiates Presto’s flagship series from Myst and its clones in my mind: I actually like The Journeyman Project better than any of them. Right from the start, there was an ambition about Presto’s approach to their fiction and their world-building that didn’t reach Cyan until they turned their focus to Riven, the big sequel to their zeitgeist-defining hit. Presto rejected the surrealism that was Myst’s hallmark; they wanted to take you somewhere you could really believe in. Their execution of their ambitions was often imperfect, but no studio was more wedded to the idea of games as coherent fictions during the 1990s. The body of work that resulted from their commitment is among the most distinctive and memorable of the decade. Whatever else you can say about them, you can’t say that Presto Studios didn’t have a unique vision. Although they wouldn’t be commercially rewarded for that vision to anywhere near the same extent as Cyan, I for one found The Journeyman Project even more interesting to revisit than Myst all these years later.

There is an important precursor to the games of both Presto and Cyan, one which probably should have appeared in these histories of mine long before this point. In 1991, Reactor, Inc., a company previously known primarily as the purveyors of a naughty CD-ROM-based “girlfriend simulator” called Virtual Valerie, published a new Mac game called Spaceship Warlock, which advertised itself as an interactive science-fiction flick. Largely inspired by the genre-blending “interactive movies” of Cinemaware that were popular on the Commodore Amiga during the late 1980s, Spaceship Warlock hewed to its chosen metaphor so stubbornly that you didn’t save your “game” from its menu when you decided to take a break; you saved your “movie” instead. In truth, it wasn’t much of a game or a movie, being short, clichéd, relentlessly linear, and supremely unchallenging, good for a couple of evenings’ entertainment at best. It was, one might say, more of a proof of concept for the fast-approaching multimedia future than a real game to be enjoyed in the here and now. Nevertheless, it made a big impression on Mac users, who had never seen anything quite like it.

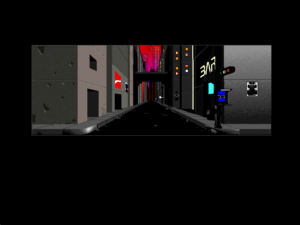

Spaceship Warlock used a lot of grid-like layouts, such as this city street. They lent themselves very well to node-based navigation, soon to be one of the hallmarks of The Journeyman Project, Myst, and countless “Myst clones.”

A young go-getter named Michel Kripalani, the proprietor of a two-year-old multimedia-services provider called Move Design in San Diego, was among those struck by Spaceship Warlock. At the age of 23, he decided to found his second company already to make a game in the same vein. He recruited four other would-be multimedia revolutionaries to join him in a ramshackle old house, where they could work on their game every evening after getting home from their day jobs. Thanks to one of their number named Dave Flanagan, an old high-school buddy of Kripalani who had a flair for writing, the game’s fiction was more fully developed than that of Spaceship Warlock. It was a time-travel story.

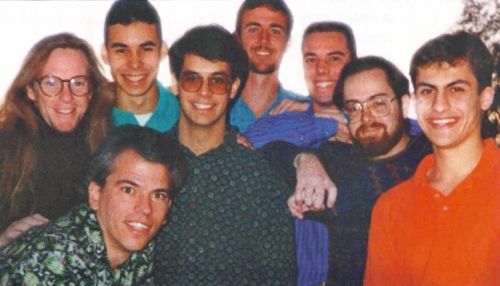

The Presto gang in the early days. Michel Kripalani is the fellow in the dark glasses; Dave Flanagan is second from right.

It is the year 2318. A time machine has recently been invented, only for the technology to be banned just as quickly in light of the threat it poses to humanity’s very temporal conception of itself. Unfortunately, the inventor of the machine has found a way to use it on the sly anyway, and has started mucking about with the past. You play a member of the Temporal Security Agency, a secret police force created for just such a contingency as this one. You must repair the damage that has been done to three different times, all of them well into the future from our perspective as 20th- or 21st-century gamers, and neutralize the mad scientist who is responsible for it.

Presto Studios, as the little group of friends had chosen to call themselves, took a bare-bones demo of the game they called The Journeyman Project to the big annual Macworld conference in January of 1992. It was very positively received there. Suitably inspired, Michel Kripalani and the others quit their day jobs. More people came onboard; the team expanded to nine, filling the original house plus a second one in the same neighborhood. Video shoots were arranged, for what would a 1990s multimedia adventure game be without real actors inserted over the computer-generated backgrounds? With the game’s high system requirements — a thirteen-inch color screen, eight megabytes of memory, and of course a CD-ROM drive — on the already niche platform that was the Macintosh, none of the mainstream game publishers showed much interest. So, Presto decided to publish it themselves, out of those same two suburban houses.

The Journeyman Project series would often be labeled Myst clones in the years to come –– but, if so, this first Journeyman Project well and truly put the cart before the horse. Certainly it uses an interface that we would still describe as Myst-like today: first-person, node-based navigation built from pre-rendered 3D graphics. And yet it was pronounced finished by Presto in January of 1993, nine months before Myst’s release and just in time for the next Macworld. No shrinking violet, Kripalani made sure the box was emblazoned with slogans like “The World’s First Photorealistic Adventure Game!” and “the game that will change history!” (A clever double meaning there…) It likewise trumpeted the participation of actor Graham Jarvis, “who guest-starred in the ‘Unification’ episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation!” He perhaps wasn’t a shining example of what most people would call star power, but one does what one can…

This first ever Journeyman Project game was a crude creation in comparison to what would come later. It was short, for one thing, almost as short as Spaceship Warlock. Presto tried to make up for this by making it difficult in all the wrong ways: the game was riddled with deaths that came out of nowhere, which you could learn to avoid only by suffering them once or twice or thrice. Brutal time limits were everywhere as well, while the “integrated arcade games” were exactly as good as such things normally are in adventure games. Playing it today, one gets the pervasive sense of a group of talented young idealists who haven’t quite figured out the fundamental workings of their craft as of yet, much less how to push it forward. But worst of all back in the day was the speed of the game, or rather the lack thereof. It was “programmed” using Macromedia’s Director, a piece of multimedia middleware that was no model of efficiency in its own right, even as it had to unspool its audiovisual assets from CD-ROM drives that could generally manage a transfer rate of no more than 150 kilobytes per second. Macworld magazine awarded the game the unwanted distinction of being “the slowest in a very slow medium.”

Thankfully for Presto, the novelty of productions like this one was still sufficient to overcome such objections in the minds of some hardy techno-pioneers. They sold 10,000 copies of the game in the first six months, mostly via mail order at the price of a cool $100. (One of the advantages of selling software for the Mac was that its user base tended to be well-heeled, such that they didn’t blink an eye at prices that would have been a death knell on any other platform.) Such numbers were enough to bring Presto out of their houses and into a proper office. The first order of business thereafter was to move the game to Microsoft Windows — thankfully, there was a version of Director for that platform as well — where many times the number of potential buyers awaited.

Presto signed a contract with a publisher called Sanctuary Woods, who had gone all-in on the premise that CD-ROM adventures like The Journeyman Project and the newly released Myst represented a major part of the future of digital gaming. At their publisher’s behest, Presto reworked the former game, using the latest software from Macromedia along with their own evolving technical skills to produce The Journeyman Project: Turbo! in mid-1994. It still wasn’t a great game by any means, but it did at least play considerably faster. Sanctuary Woods used the new version in a subtly ingenious way. They sold it at retail at a deep discount, whilst signing deals to get it included as an extra in the box with the turnkey multimedia computers and “multimedia upgrade kits” — a CD-ROM drive and a sound card in one convenient package — that were becoming all the rage as the multimedia revolution went mainstream. Deals such as these didn’t tend to be very profitable in their own right. They were rather meant to serve another agenda: by making the first Journeyman Project game so ubiquitous, Sanctuary Woods hoped to prime the pump for the sequel on which Presto was already hard at work.

The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time was envisioned from the start as the game that would take things to the proverbial next level. Michel Kripalani, Dave Flanagan, and Phil Saunders — the last being a new arrival who in previous lives had designed amusement-park rides and automobiles, and now held the title of Creative Director at the growing Presto Studios — spent more than five months sketching out what it should be. They wanted to make a quantum leap over the first game in terms of fiction, graphics, length, complexity… everything. Luckily, they were all fast learners.

The heretofore mostly uncharacterized player-controlled protagonist, who was referred only as “Agent 5” in the first game, got a name and a face in Buried in Time in the interest of deepening the fiction. The former is Gage Blackwood; the latter belonged to an aspiring actor named Todd McCormick. Once again, Buried in Time involves traveling into the past to right acts of vandalism against the temporal stream that have been committed by another time traveler. Now, though, the identity of the villain is not so obvious. In fact, thanks to some machinations on the villain’s part, Gage himself is Suspect Number One in the eyes of the powers that be.

The sequel opens in Gage’s apartment, where he is visited by a version of himself traveling back from the future, to warn him of the impending frame-up and tell him to get cracking on the trail of the real culprit before it’s too late. Instead of being reliant on a clumsy time machine that drags him back to the present after a certain span of time has elapsed — clock time, that is; this time-travel stuff does get confusing, doesn’t it? — Gage now has access to a “Jumpsuit,” which lets him move back and forth as he wishes. Unfortunately, if any native of any given time should see him wandering around in this bulky monstrosity, the result will be a future-destroying “temporal anomaly.” It therefore behooves Gage to keep to himself. You have to hand it to Presto: as excuses for ensuring that Myst-like adventure games remain strictly solitary experiences go, this is undeniably one of the cleverest.

There are whole layers to the fiction beyond what I’ve just described, involving diplomacy with multiple alien races and all sorts of other political concerns. As with most stories about time travel, there are plot holes in this one big enough to drive a dump truck through if you stop to think too hard about it all, but that shouldn’t detract from the love and care that went into Presto’s future history of the world. They did not want the story and setting to be “just a weak scarecrow frame on which to hang gameplay,” as 3D artist David Sieks puts it. “There was a desire to create a deeper and richer experience than the typical adventure title.” You’re likely to spend your first hour or so in Buried in Time just poking around inside Gage’s stylish bachelor pad, fiddling with the knickknacks on his shelves and taking in the news broadcasts — complete with commercials! — that are available on his television. The only contemporaneous adventure game I can think of that evinces a similar commitment to building a coherent science-fictional universe out of whole cloth, with its own history, politics, and all the other trimmings, is Legend Entertainment’s Mission Critical.

But best of all from the standpoint of many players, myself very much included, are the whens to which you get to travel in Buried in Time after you get tired of futzing around in Gage’s apartment. Three of the four are before our own time, part of the “real” history of our planet. Kripalani, Flanagan, and Saunders debated for many hours where and when those places should be, looking for ones that would be both interesting to explore and manageable to depict using the 3D-rendering technology at their disposal. Some otherwise appealing ones, such as ancient Egypt, were rejected for failing the latter test. They finally settled on three that stem from the first half of the second millennium of the Common Era: the Mayan metropolis of Chichén Itzá in 1050, an English-held castle in France in 1204, and Leonardo da Vinci’s Milanese laboratory and workshop in 1488.

Presto threw an awful lot of balls into the air in thus attempting to combine their commitment to the future history of the world they were building with an equal commitment to making the real places of our real shared past that Gage was to visit as accurate as they could be. And, lo and behold, they dropped astoundingly few of them. As a lover of the Renaissance era, my favorite part of the game is naturally Leonardo’s workshop, which you visit on a sylvan December night, wandering among the genius’s sketches and notes, paintings and inventions, from siege engines to a working elevator built using a system of ropes and locking pulleys. Sometimes knowing too much can be dangerous in these situations, as it leads you to see all of the mistakes; this time, though, it merely helped me to appreciate the re-creation that much more. I consider that to be pretty high praise.

But perhaps the highest praise of all that I can offer Buried in Time is that it made me forgive if not always forget most of the things that tend to make Myst-style adventure games such a hard sell for me, even though those things are still very much present here. When you rotate the view, for example, your degree of rotation is inconsistent; sometimes it’s 90 degrees, sometimes less or more. This introduces a note of fake difficulty, as the simple act of moving about a space, which would be trivial if you were really in the world, suddenly becomes a complicated endeavor in itself. You can stumble around even in Gage’s little apartment for quite some time looking for the “exit” to the node that plants you in front of the television or the kitchen counter, to say nothing of the other, larger and more complicated spaces. Just to make it all even more convoluted, you can now look up or down as well as straight ahead from each node. And make no mistake, you have to check every single view carefully to ensure that you don’t miss a hidden exit to another node, or that little thingamabob that you’ll need to solve a puzzle somewhere (or, more likely, somewhen) else.

In some areas, however, Buried in Time does find ways to remedy the things that typically frustrate me about Myst-like games. In the year 2247 — the one time you visit from Gage’s past that still lies in our future — you can pick up an irreverent “artificial intelligence” named Arthur, who’s a heck of a lot more fun than ChatGPT. He integrates himself with your Jumpsuit to become your boon companion, offering up a steady stream of banter, ideas, and, most vitally, explanations of the historical places you visit. He functions, that is to say, much like Dalboz, the magic-lantern-imprisoned Dungeon Master whom Zork: Grand Inquisitor later employed so effectively to relieve the pangs of solitude.[1]Laird Malamed, who led the Zork: Grand Inquisitor project at Activision, told me that he had played and enjoyed Buried in Time, but that he can’t remember consciously modeling Dalboz on Arthur. He says the disembodied Dungeon Master was a case of making a virtue out of a necessity: “I had fired the actor I wanted to play Dalboz onscreen.” Somewhat surprisingly to me, some players wind up loathing Arthur. For my part, though, I can hardly imagine Buried in Time without him. By no means do all of his jokes land, but he gives the game personality, keeps you from ever feeling too alone in the usual Myst way, and of course tells you what it is you’re actually looking at in 1050, 1204, and 1488.

The twisty little passages of a Medieval castle. Yes, the view window is always that small, leaving lots of room for cyber-punkish gadgetry all around it. This game is certainly not cleanly, classically minimalist like Myst. Yet the crazily elaborate diegetic interface of your Jumpsuit does add to the mimesis. What can I say? You get used to it.

Floating outside the space station where you can find Arthur. One flaw in the design is an ironic consequence of its determined non-linearity: you can complete a goodly portion of the game before you meet Arthur, thus losing out on a lot of the historical context he lends with his banter. So, you might want to prioritize the year 2247 in the beginning…

The courtyard of Leonardo da Vinci’s workshop. This may not look like a maze, but just wait until you try to navigate it using these controls…

All told, then, Buried in Time really is the quantum leap over its predecessor that Presto intended it to be. It’s not an easy game, but it’s not an unfair one either. The frequency and variety of possible deaths is toned down in comparison to what came before, and they can more often be attributed to you doing something ill-advised than the game just deciding to randomly screw you over. I was able to finish Buried in Time without ever peeking at a hint, walking away proud of both myself and the game that had challenged but never undermined me. There are plenty of silly bits to it, but there’s a gravitas to the whole that comes through despite the silliness, a gravitas that most Myst clones lay claim to as if it is theirs by right but never even attempt to actually earn. Buried in Time’s, by contrast, is weirdly effortless, a byproduct of its steadfast commitment to both its future and past history and to its fiction in general.

Sanctuary Wood published Buried in Time in the summer of 1995. Even the hardcore-gaming press, which tended not to be overly friendly to games made by studios like Presto (or Cyan, for that matter), had to acknowledge that this was not your garden-variety Myst clone. The noted Myst hater Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World magazine admitted that “I didn’t expect to like Buried in Time,” then went on to tell why he ended up doing so after all.

There is no way to move backward; there is no way to move sideways. This is a pain. When you’re trying to race out of Richard the Lionhearted’s bedchamber before his guards discover you, it’s a royal pain. And when you’re in the castle stairwell with a knight waving his blade at you, I am afraid it can turn out to be a bloody pain.

But Buried in Time is an enormously satisfying game in spite of all this. You know it as soon as the game starts, deep in your gut where such knowledge always lurks. It’s the feeling you get ten minutes into a movie when you know the next hundred minutes will be sheer joy. Buried in Time’s opening sequence sets up an intriguing premise and a highly charged level of suspense. And despite the game’s weaker points, it never lets you down from this early high.

Speaking of highs: that summer of 1995 was just about exactly the commercial peak of the multimedia adventure game writ large. Helped along by its fortuitous release date, by positive reviews like Charles Ardai’s, and by Sanctuary Woods’s savvy priming of the pump with The Journeyman Project: Turbo!, Buried in Time became a solid second-tier hit, selling 225,000 copies. Presto reveled in the praise and sales, took a deep breath, and augmented their programming staff for a third game in the series, which was finally to abandon Macromedia Director in favor of a proper, in-house-developed game engine of Presto’s own.

As that project was proceeding, however, the adventure genre’s commercial forecast was being clouded by games like DOOM, Warcraft, Command & Conquer, and eventually Quake. The year of 1996 became the first in half a decade not to produce any new million-plus-selling breakout adventure blockbuster, only a plethora of nearly or barely profitable would-be contenders for that status. Sanctuary Woods, finding themselves over-invested in games superficially similar to but usually not as good or as financially rewarding as Buried in Time, sold out to Disney Interactive in May of that year. As a Disney subsidiary, they were to refocus on children’s software, leaving Presto suddenly bereft of the publisher who had played such a big role in Buried in Time’s success.

In the face of these headwinds, Presto, like a fair number of other studios who found themselves in much the same boat, began to cast a hopeful eye outside the traditional computer-gaming space. Some big technology players still believed in the potential of a multimedia set-top box for living rooms, a games console but also more. Apple was among them; it had entered into a partnership with Bandai, a Japanese electronics manufacturer, to make just such a thing, to be called the Pippin. And then there was the Sony PlayStation, the machine that was in the process of unseating Nintendo from its throne as the king of console gaming. The PlayStation sported not only a built-in CD drive and the ability to save state from session to session but a user base that skewed older than the one Nintendo had always courted. If Presto could bring The Journeyman Project to platforms like the Pippin and the PlayStation, who knew how far they could take it?

They decided the best way to introduce this new demographic to the world of The Journeyman Project was to tell the story from the beginning. A team at Presto was set to work remaking the first game in the series, programming it, like the still-in-progress third game, in C++ rather than relying on Macromedia Director. Journeyman Project: Pegasus Prime was to be an ideal introduction to adventure games for folks reared on WipEout and the like, being slick and quick to play, with all of the frustrations that had dogged its earlier incarnations smoothed away. For this bunch of creators who were so fixated on crafting coherent fictions as well as fun games, taking the time to do the remake was no real sacrifice at all. On the contrary, it allowed them to ret-con a lot of the additional fictional layers of Buried in Time back into the first story, including Gage Blackwood himself. He was once again played in Pegasus Prime by Todd McCormick, and much of the rest of the cast from Buried in Time returned as well.

And like Buried in Time, the end result succeeds marvelously in being exactly what it was intended to be. In fact, I must confess that, had Pegasus Prime never been made, I probably wouldn’t be writing this article about The Journeyman Project as a whole today. I bounced hard off of the original version of the first game several years ago, and largely wrote the series off as all too typical artifacts of their time, made by people who were better at babbling about a multimedia revolution than they were at making playable games. Only late in the day did I decide to take a flier on Pegasus Prime, just to see. I’m very glad I did so. It comes about as close as any adventure game of this stripe ever has to earning the label of “thrill ride.” Only one puzzle, coming right at the end, stumped me for more than a minute or two. And you know what? I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Sadly, Presto’s grand plans for Pegasus Prime all fell through. The Pippin barely made it to market before it was discontinued, while a deal with Acclaim Entertainment to publish the game for the PlayStation was nixed at the last minute, when Acclaim abruptly decided it wasn’t worth the trouble. Bandai Digital Entertainment released Pegasus Prime for the Mac with little fanfare in the fall of 1997, strictly to satisfy their contract with Presto. The remake was barely noticed even in Apple World amidst the excitement over Steve Jobs’s return and rumors of the forthcoming iMac. In business if not artistic terms, the whole project was Presto’s first significant misstep, a lot of money spent for no return whatsoever.

But through it all they had also continued with The Journeyman Project 3: Legacy of Time, which was ready to go for Mac and Windows by the beginning of 1998. They found a more auspicious publisher for this game: Red Orb Entertainment, the new games label of the venerable Brøderbund Software, the publisher of Myst and, most recently, its million-plus-selling sequel Riven. All of this seemed to bode very well indeed.

The fan consensus has it that Legacy of Time is a step down from Buried in Time, and with this I must largely concur. At the same time, however, it’s a fine game in its own right. Gage Blackwood is played for some reason by the actor Jerry Rector this time, but most of the rest of the old cast has returned. That list includes the voice actor Matt Weinhold in the role of Arthur, your disembodied, wise-cracking, information-spewing companion in adventure. Once again, Gage and Arthur must delve into the past to correct the time stream and prevent the end of human civilization as they know it (which does rather lead one to wonder whether someone oughtn’t to just travel back in time and prevent these troublesome time machines from being invented in the first place).

Technologically speaking, Legacy of Time is streets ahead of Buried in Time and even Pegasus Prime; not only is your view of the world sharper and more detailed than ever before, filling much more of the screen now, but within each node you can smoothly pan the view up, down, and sideways. Thanks to this innovation and many others, Legacy of Time feels less like a Myst clone than ever. Gage now has access to a “chameleon” version of his Jumpsuit, which lets him take on the appearance of a native in the times and places he visits, so that he can actually talk to the people there. It’s a brave choice on Presto’s part, emblematic of the thoroughgoing determination to try new things and push the boundaries that remained one of the trademarks of the Journeyman Project series from beginning to end. As a result of it, this Journeyman Project feels more alive than ever before. Although the onscreen actors you encounter in three more times and places from our planet’s past don’t hesitate to ham it up a little, they’re clearly professionals having fun rather than amateurs fumbling their way through their roles. Between chapters of the story, Jerry Rector and his colleagues in the future chew their way through what amounts to a little sci-fi B-movie all its own. These interstitial cut scenes, which often stretch to several minutes in length, aren’t bad at all by the cheesy standards of their breed.

And yet, just as Buried in Time somehow transcends its clunkier aspects, Legacy of Time comes off perhaps a little bit less well than a game made with such evident love and care ought to. The times and places you visit are the biggest source of disappoint for me. Instead of engaging with real history, as Buried in Time did so earnestly and successfully, Legacy of Time treads perilously close to the pseudo-history promulgated by fabulists like Erich von Däniken and Graham Hancock; it sends you to Plato’s legendary lost city of Atlantis, to the Peruvian “city of gold” El Dorado, and to the mythical kingdom of Shangri La, nestled here high in the mountains of Nepal. All of these environments are rendered beautifully, even evocatively, but they still make the game feel more generic than its predecessor. I think most of us can probably agree that there ought to have been a moratorium on the use of Atlantis in adventure games a long, long time ago.

Then, too, some of the purported technical improvements in Legacy of Time wind up cutting both ways. The cleaner interface that gives a much larger window on the world you’re exploring seems like it should be an unmitigated good thing, but it turns out that the fiddly, almost cyberpunk look and feel of Buried in Time contributed more to the fiction than even Presto might have realized. The more elaborate filmed sequences likewise subtract as well as add, by making Legacy of Time feel that much less like your adventure. Beyond these obvious things, it’s hard to give a precise name to what is missing from Legacy of Time — call it gravitas; call it soul if you absolutely must — but many players in addition to myself have felt its absence.

Jerry Rector is Gage Blackwood, two-time hero of the Temporal Security Agency. Care to make it three times?

The jungles of Peru, where El Dorado is hidden. Notice the silhouette at the bottom center of the screen. That tells us who the chameleon Jumpsuit is currently showing us to be (in this case, a little boy). We can switch to other personas whenever we like, as long as no one is watching. Doing so is key to solving many of the puzzles.

Alas, this third game in the series was a commercial disappointment as well. For many years one of the best promoters and popularizers in their industry — witness what they had done with Myst! — Brøderbund was distracted as they were releasing Legacy of Time in February of 1998, being in the throes of an acquisition by The Learning Company that would be finalized that August. Their promotional efforts were feeble — although, to be fair, full-fledged interactive movies, which The Journeyman Project series seemed to be fast becoming, were beginning to look even more passé than Myst clones in early 1998. Brøderbund may simply have decided it wasn’t worth beating a dead horse after they saw the product that Presto delivered.

A fourth Journeyman Project game never got beyond the early prototyping stage at Presto, who now embarked on an urgent technological retooling in the hope of keeping their head above water in this changed industry, where 3D graphics were expected to be real time rather than pre-rendered and action games ruled the roost more than ever. Fortunately for them, they would soon be thrown a life preserver with the logo of Myst itself — seemingly the one Sure Thing still left in adventure gaming — emblazoned on the front.

We’ll get to that story at a later date. Today, though, let me warmly recommend The Journeyman Project to all of you. Although Buried in Time is the clear standout in the group in my opinion, both Pegasus Prime and Legacy of Time are well worth playing in their own right, suffering only by comparison with the companion piece that stands so tall between them.

In what order should I tackle them, you ask? Well, I wouldn’t be the first person to start my answer to that question by musing on the irony of the temporal confusion that dogs this series of games about time travel, almost as if a rogue inventor went back and scrambled their chronology too. Once I was done doing that, however, I’d recommend prioritizing the internal chronology of the series: start with Pegasus Prime, which has now been digitally re-released for Windows as well as the Macintosh, finally allowing it to fulfill the role Presto always envisioned for it as your introduction to the Journeyman Project universe. Then you can go on to Buried in Time, followed by Legacy of Time. This progression won’t be completely unjarring — suffice to say that you’ll definitely be able to see that Buried in Time is an older game than Pegasus Prime — but the middle game is good enough that you’ll quickly get over the shock of its smaller, blurrier window on the world. Whatever order you choose to play them in, my most important recommendation is to take your time with the games, to let them live in your consciousness the way you might a good book.

Michel Kripalani loves to boast today about how Presto consistently lived on the “bleeding edge” of technology. He’s not wrong in saying this, yet he ironically misses what really made these games special. If they were notable only for their technology, they would be remembered today, now that the state of the art has all too plainly moved on, as mere stepping stones to better interactive experiences. They’re made well worth playing as well as remembering today by their makers’ absolute commitment to their fictions, as demonstrated in their doggedly diegetic interfaces, by the countless little details in their worlds that exist only to further the cause of immersion rather than having anything to do with helping you to “solve” them, even by Presto’s compulsion to remake the first game over and over. (One suspects that, if the series had only lasted a bit longer, they would soon have been turning a jaundiced eye upon Buried in Time as well…)

In light of all this, I was momentarily tempted to complain here that it was Cyan’s Myst rather than these deeper virtual worlds that sold millions of copies and reshaped a portion of the gaming landscape in its image. But of course that’s unfair; Myst is possessed of its own brilliant qualities, of accessibility and universality. The Journeyman Project dared to ask a lot more of its players, which necessarily hindered its mass acceptance. But if you can meet it where it lives, you might be surprised how quickly the patina of age fades away, leaving you with an interactive story that can pull you in every bit as completely as any newer, sexier virtual reality. Whether told around a campfire or on a monitor screen, ripping yarns like these ones have no sell-by date.

The Legacy of Time Jumpsuit, a prop that cost $25,000 to have made, is on display today at the Science and Engineering Library of the University of California, San Diego, the alma mater of Michel Kripalani and a number of other Presto Studios principals.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book The Secret History of Mac Gaming by Richard Moss; Game Developer of December 1995/January 1996 and December 2002; Computer Gaming World of July 1993, April 1994, November 1995, January 1998, and April 1998; Next Generation of March 1997; InterActivity of January 1996; Macworld of October 1991, February 1993, May 1993, July 1993, and September 1993; MacFormat of July 1994.

Online sources include an Adventure Classic Gaming retrospective of The Journeyman Project by Peter Rooham-Smith, an article by the same author about Pegasus Prime alone, a brief piece about Michel Kripalani from The UCSD Guardian, and Kripalani’s appearance on the Habits2Goals podcast.

The Journeyman Project 1: Pegasus Prime, The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time, and The Journeyman Project 3: Legacy of Time are all available for digital purchase on GOG.com.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Laird Malamed, who led the Zork: Grand Inquisitor project at Activision, told me that he had played and enjoyed Buried in Time, but that he can’t remember consciously modeling Dalboz on Arthur. He says the disembodied Dungeon Master was a case of making a virtue out of a necessity: “I had fired the actor I wanted to play Dalboz onscreen.” |

|---|