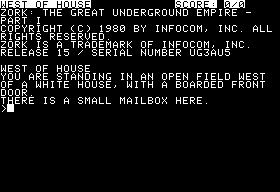

With Zork on the market and proving to be a major hit, it was time for Infocom to think about the inevitable sequel. The task of preparing it fell to Dave Lebling. At first glance, it looked straightforward enough. He needed only take the half of the original PDP-10 Zork that had not made it into the PC version, label it Zork II, and be done with it. In actuality, however, it was a little more complicated. The new game would at a minimum have to have some restructuring. For example, the goal of the PDP-10 Zork, like the PC version, was to deliver a collection of treasures to the white house outside of which the player started the game. Yet in Zork II said house would not exist. Perhaps motivated at first largely by necessity, Lebling began to tinker with the original design. Soon, inspired by the new ZIL technology Infocom had developed to let them port Zork to the PC, technology that was actually more flexible, more powerful, and simpler to work with than the MDL behind the original Zork, Lebling began to dramatically reshape the design, interspersing elements from the original with new areas, puzzles, and characters. In the end, he would use only about half of the leftover PDP-10 material, which in turn would make up about half of Zork II; the other half would be new. Lebling thus became the first implementer to consciously craft an Infocom game, for sale as a commercial product on PCs.

To the outside world, Infocom now began to establish the corporate personality that people would soon come to love almost as much as their games — a chummy, witty inclusiveness that made people who bought the games feel like they had just signed up for a “smart persons club.” Rather than one of the Zork creators or even one of the Infocom shareholders, the organizer and guider of the club was Mike Dornbrook, a recent MIT biology graduate who had come to Zork only in 1980, as the first and most important playtester of the PC version.

More than anyone else around Infocom, Dornbrook was a believer in Zork, convinced it was far more than an interesting hacking exercise, a way to get some money coming in en route to more serious products, or even “just” a really fun game. He saw Zork as something new under the sun, something that could in some small way change the world. He strongly encouraged Infocom to build a community around this nascent new art form. At his behest, the earliest version of Zork included the following message on a note in the artist’s studio:

Congratulations!

You are the privileged owner of a genuine ZORK Great Underground Empire (Part I), a self contained and self maintaining universe. As a legitimate owner, you have available to you both the Movement Assistance Planner (MAP) and Hierarchical Information for Novice Treasure Seekers (HINTS). For information about these and other services, send a stamped, self-addressed, business-size envelope to:Infocom, Inc.

GUE I Maintenance Division

PO Box 120, Kendall Station

Cambridge, Mass. 02142

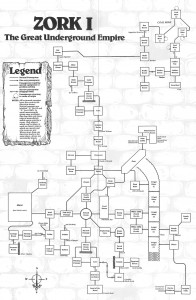

Joining the smart-persons club was at this stage still quite a complicated process. The aforementioned self-addressed envelope would be retrieved by Stu Galley, who dutifully visited the post office each day. He then sent back a sheet offering a map for purchase, as well as the ultimate personalized hint service; for a couple of dollars a pop, Infocom would personally answer queries.

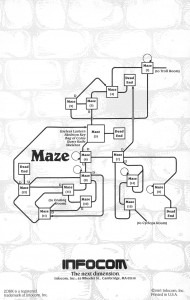

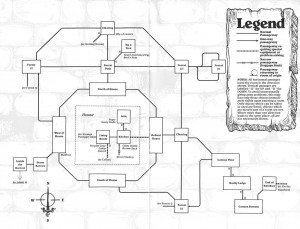

The map was adapted from Lebling’s original by Dave Ardito, an artist friend of Galley’s who embellished the lines and boxes with some appropriately adventurous visual flourishes. Dornbrook, who had some experience with printing, used his MIT alumni status to print the maps in the middle of the night on a big printing press that normally produced posters and flyers for upcoming campus events. He enlisted his roommate, Steve Meretzky, to help him.

Meretzky was also an MIT alum, having graduated in 1979 with a degree in construction management. He may have gone to the most important computer-science university in the world, but Meretzky wanted no part of that world. He “despised” computers and hackers. In Get Lamp‘s Infocom feature, Dornbrook described Meretzky’s introduction to Zork. Dornbrook was testing the game, and had borrowed a TRS-80 and brought it home to their apartment, where he set it up on the kitchen table.

He [Meretzky] came in the back door and saw the computer and said, “Away!” as only Steve could. I started telling him, “Steve, you’re going to love this!” I was trying to explain to him how to start the game up, and he puts his hands over his ears and starts screaming so he can’t hear me.

But apparently he heard enough. Over the course of the next several weeks, I started noticing when I’d come home and was about to start testing again that the keyboard might have moved half an inch or my notes had moved slightly. I realized Steve was playing the game but wasn’t willing to admit it. One night he finally broke down and said, “Alright! Alright! I need a hint!” And that was the beginning of the end for Steve.

Meretzky soon signed up as a tester, and also joined Dornbrook in his other Infocom-related projects.

There’s a great interview amongst the Get Lamp extras with David Shaw, an MIT student who wrote for the campus newspaper, whose offices were just above the press Dornbrook and Meretzky were surreptitiously borrowing. Shaw was confused by the fact that the press “always seemed to be running,” even when there were no new campus events to promote: “There were always the same two or three guys down there. They were printing something out that clearly wasn’t a movie poster, but they were also being very cagey about what it was they were printing.” One day Shaw found Dornbrook and Meretzky’s apparent “discard pile” of Zork maps and realized at last what was going on.

While the maps were a team effort, hints fell entirely to Dornbrook. He hand-wrote replies on ordinary paper. After a time he found it to be quite a profitable, if occasionally tedious, endeavor. Because most of the queries were variations on the same handful of questions, crafting personal answers didn’t take as much time as one might expect. (See the Infocom section of the Gallery of Undiscovered Entities for scans of the original maps and, even better, a couple of Dornbrook’s handwritten replies to hint requests.)

Then Dornbrook was accepted into an MBA program at the University of Chicago, scheduled to begin in the fall, meaning of course that he would have to leave Boston and give up day-to-day contact with the Infocom folks. No one else felt equipped to replace Dornbrook, who had by this point become in reality if not title Infocom’s head of public relations. Dornbrook, concerned about what would happen to “his” loyal customers, tried to convince President Joel Berez to hire a replacement. Impossible, Berez replied; the company just didn’t yet have the resources to devote someone to nothing but customer relations. So Dornbrook pitched another idea. He would form a new company, the Zork Users Group, to sell hints, maps, memorabilia, and even Infocom games themselves at a slight discount to eager players who joined his new club, which he would run out of Chicago between classes. Infocom in turn would be relieved of this burden. They could simply refer hint requests to Dornbrook, and worry only about making more and better games. Berez agreed, and ZUG was officially born in October of 1981. It would peak at over 20,000 members — but more about that in future posts.

Through much of 1981, Infocom assumed that Personal Software, publisher of the first Zork, would also publish Zork II. After all, Zork was a substantial hit. And indeed, PS responded positively when Infocom first talked with them about Zork II in April. The two companies went so far as to sign a contract that June. But just a few months later PS suddenly pulled the deal. Further, they also announced that they would be dropping the first Zork as well. What happened? wondered Infocom.

What had happened, of course, was VisiCalc. Dan Fylstra, founder of PS, had nurtured Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston’s creation from its very early days, donating an Apple II to the pair to help them develop their idea. Once released in October of 1979, VisiCalc transformed the microcomputer industry — and transformed its publisher. PS, formerly a publisher of games and hobbyist programs, was suddenly “the VisiCalc publisher,” one of the hottest up-and-coming companies in the country. As big as Zork was, it didn’t amount to much in comparison to VisiCalc. By 1981 games and hobbyist software made up less than 10 percent of PS’s revenue. Small wonder that Infocom often felt like their game was something of an afterthought for PS. Now the IBM PC was on the horizon, and PS found itself being courted even by the likes of Big Blue themselves, who needed for VisiCalc to be available on their new computer. Just as Microsoft was also doing at this time, PS began to reshape themselves, leaving behind their hacker and hobbyist roots to focus on the exploding market for VisiCalc and other business software. They began doing in-house development for the first time, rolling out a whole line of programs to capitalize on the VisiCalc name: VisiDex, VisiPlot, VisiTrend, VisiTerm, VisiFile. The following year PS would complete their Visification by renaming themselves VisiCorp, en route to disappearing up their own VisiBum in one of the more spectacular flameouts in software history.

In this new paradigm Zork was not just unnecessary but potentially dangerous. Games were anathema to the new army of pinstriped business customers suddenly buying PCs. Companies like PS, who wished to serve them and be taken seriously despite their own questionable hacker origins, thus began to give anything potentially entertaining a wide berth. The games line would have to go, victim of the same paranoia that kept Infocom’s own Al Vezza up at night.

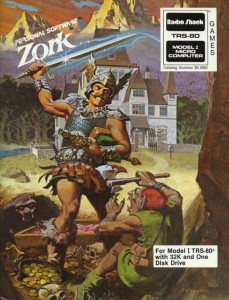

This rejection left Infocom at a crossroads. It wasn’t, mind you, a disaster; there would doubtlessly be plenty of other publishers eager to sign them now that they had a hit game under their belt. Yet they weren’t sure that was the direction they wanted to go. While there was a certain prestige in being published by the biggest software publisher in the world, they had never really been satisfied with PS. They had always felt like a low priority. The awful Zork “barbarian” packaging PS had come up with made one wonder if anyone at PS had actually bothered to play the game, and promotion efforts had felt cursory and disinterested. Certainly PS had never shown the slightest interest in helping Infocom and Dornbrook to build a loyal customer base. If they wanted to build Infocom as a brand, as the best text adventures in the business, why should they have another company’s logo on their boxes?

But of course becoming a publisher would require Infocom to become a “real” company rather than one that did business from a P.O. Box, with more people involved and real money invested. In a choice between keeping Infocom a profitable little sideline or, well, going for it, the Infocom founders chose the latter.

Several of them secured a substantial loan to bankroll the transition. They also secured a fellow named Mort Rosenthal as marketing manager. He lasted less than a year with Infocom, getting himself fired when he overstepped his authority to offer Infocom’s games to Radio Shack at a steep discount that would get them into every single store. Before that, however, he worked wonders, and not just in marketing. A natural wheeler and dealer, he in Stu Galley’s words secured “a time-shared production plant in Randolph, an ad agency in Watertown, an order-taking service in New Jersey, a supplier of disks in California, and so on,” all in a matter of weeks. He also found them their first tiny office above Boston’s historic Faneuil Hall Marketplace. The first two salaried employees to come to work there became Berez, the company’s most prominent business mind, and Marc Blank, the architect of the Z-Machine who had already more than a year before set aside his medical internship and moved back to Boston to take a flyer on the venture.

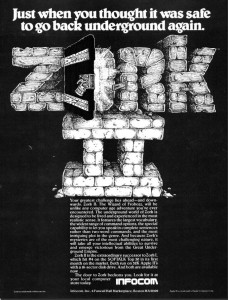

Showing an instinct for public perception that’s surprising to find in a bunch of hackers, Infocom made one last deal with PS — to buy back PS’s remaining copies of Zork and prevent them from dumping the games onto the market at a discount, thus devaluing the Zork brand. They needed to have Zork II out in time for Christmas, and so worked frantically with the advertising agency Rosenthal had found to craft a whole new look for the series. The motif they came up with was much more appropriate and classy than the old PS barbarian. In fact, it remains the established “look” of Zork to this day.

Ironically for a company whose games were all text, Infocom’s level of visual refinement set them apart, not least in the classic logo that debuted at this time and would remain a fixture for the rest of the company’s life. But speaking of text: in Zork II‘s advertising and packaging we can already see the rhetorical voice that Infocom fans would come to know, a seemingly casual, humorous vibe that nevertheless reflected an immense amount of care — this at a time when most game publishers still seemed to consider even basic grammar of little concern. In comparison to everybody else, Infocom just seemed a little bit classier, a little bit smarter, a little bit more adult. It’s an image that would serve them well.

Next time we’ll accept the invitation above and dive into Zork II itself, which did indeed make it out just in time for Christmas.