As earlier posts have hopefully made clear, conventions played a pivotal role for many years in the PC industry. In the early years that meant places like the West Coast Computer Faire and the AppleFests, where hackers and hobbyists would gather to talk about their machines and trade tips along with manufacturers, publishers, and developers; indeed, in this early period the groups could be all but indistinguishable. But 1982 is generally remembered by old-timers as the last year when the likes of Applefest could attract the movers and shakers. Afterward, as the moneyed interests entered en masse and the community of computer users (or even Apple users) grew too large to retain that clubby feeling, such gatherings faded in importance in comparison with the glitzier Consumer Electronics Show and its rivals, where you needed a press badge just to get in. Whatever form the shows took, they were as important for what took place behind the scenes, in back rooms, bars, and hotels, as what was shown on their floors. In gathering people from all over the industry together in one location, they provided essential opportunities for negotiations, deal making, maybe even a bit of intrigue.

Thus it was at the Boston Applefest in May of 1982 that Marc Blank of Infocom had a long talk with Mike Berlyn of Sentient Software, to whom he had been introduced by a mutual acquaintance. As it turned out, each was looking for something the other could offer him. It didn’t take long to make a deal.

Berlyn was by a wide margin the more frustrated of the pair. As you may recall, he had embraced the idea of adventure games as a new form of literary expression very early, and put it into practice as well as his resources allowed in two games he released through Sentient, Oo-Topos and Cyborg. Yet despite an absolutely rapturous review of the latter in the influential Softalk, the two games made nary a dent commercially. Berlyn, a demanding personality who throughout his career would change business relationships almost as often as he churned out games, felt muzzled by partners he felt weren’t as committed as he was and the accompanying lack of promotion and investment. Still, he also realized that in a real sense his best just wasn’t good enough. Both games were written in BASIC, with the two-word parser, simplistic world model, and all the other limitations that implied. Berlyn was a clever self-taught Apple II hacker, but lacked the experience or technical vision to create something more advanced — like, say, Infocom’s state-of-the-art ZIL system.

Blank, meanwhile, had ZIL but wasn’t sure he could take full advantage of it. Since starting to work on the landmark Deadline the previous year, he had started to see Infocom’s games in much the same light as Berlyn — as dynamic, playable stories. Blank, who was rather insecure about his own writerly chops (albeit largely unnecessarily), now viewed Deadline almost as a tech demo, a chance to get tools worked out and to demonstrate some shadow of what might be possible in the hands of a real writer. Berlyn, it must be admitted, was not exactly Norman Mailer or even Arthur C. Clarke. He had just three straight-to-the-dimestore-paperback-rack science fiction novels to his credit, none of which had sold all that well. Still, that was enough to qualify him for the title of “published author,” and was also three more novels than anyone else currently writing adventure games had published. Signing Berlyn would mark a big step toward Blank’s crystallizing vision of Infocom as publishers of interactive fiction rather than mere text adventures, even if it would still be a couple of years before the company would stumble upon that term to describe what they were really about.

The first plan had Berlyn working on a game for Infocom under contract from his home in Colorado. However, what with the complexities of the ZIL system and the state of telecommunications in 1982, that quickly proved impractical. So, within weeks of the Applefest meeting, Berlyn and his wife packed up and moved to Boston, where he became one of the first full-time employees to be hired by Infocom, as well as the first Implementor to be drawn from outside the immediate orbit of MIT’s Laboratory for Computer Science. What Infocom got for a first project was perhaps not quite what they had expected. Berlyn, Infocom’s supposed literary star, always combined a headstrong creativity with a certain flair for the perverse. He now started in earnest on Suspended, arguably the least literary parser-driven game Infocom would ever release, more a strategy game implemented in text than an interactive fiction.

The premise of Suspended reflects a longstanding obsession of Berlyn with disembodied consciousness; this had already been at the heart of his novel The Integrated Man and his earlier adventure Cyborg. In Suspended, you take the role of, yes, another disembodied consciousness, whose body has been placed in “cryogenic suspension” while her mind takes a 500-year shift as the emergency backup to an automated system which makes life possible on a planet of the future, controlling the weather, food production, and the transportation network. Normally your mind sleeps alongside your body, but you’re to be woken in the case of an emergency which the automated systems are not equipped to handle. As you’ve probably guessed, just such an emergency occurs as the game begins.

With no body of your own, you have six robots to whom you can issue orders and through whose senses you can experience the game’s available geography, which is restricted to a planetary control complex located far underground. Each robot is somewhat, um, specialized in its capabilities. Iris is the only one who can see. Auda can hear. Sensa can detect “vibrational activity, photon emission sources, and ionic discharges.” Poet seems to have no clear purpose, other than to spout bits of poetry that must be deciphered like a code to figure out what is really going on with him. (“All life’s a stage, so just consider me a player,” he says when asked to go somewhere; “It hops and skips and leaves a bit, and can’t decide if it should quit,” when asked to describe his surroundings inside a power station.) The most obviously practical robots are Whiz, who can interface with various computer systems, and Waldo, a general-purpose repair robot.

Over the course of the game a series of escalating crises strike the planet, to which you must respond by making use of all of your robots. There are fairly conventional object-based puzzles to solve, but even once you figure out how to do everything you still face a daunting challenge in scheduling and logistics to juggle all of your robots efficiently and minimize the casualties on the surface. If you succeed in saving the planet at all — no easy task in itself; it will likely take dozens of plays just to get that far — you next can concentrate on doing it without leaving half the population dead. (It’s rather deflating when you “win” for the first time, only to be told that the survivors want to burn you in effigy.) Winning “a home in the country and an unlimited bank account” will likely take at least a few dozen more attempts.

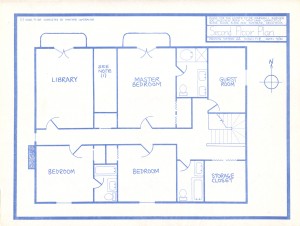

Played today, Suspended feels oddly like a genre of cooperative board games that have become fairly common in recent years. In games like Pandemic, Red November, and Flash Point, players struggle together to maintain a system against a series of shocks, whether they come in the form of waves of global disease, leaks and explosions aboard a very unseaworthy submarine, or a hungry house fire. Further cementing the board-game connection in my mind are the uniquely practical feelies that came with Suspended: a map of the complex in the form of a game board, with a set of counters representing each of the robots. As you get deeper into the game and begin playing to win you’ll soon have multiple robots moving simultaneously about the complex doing various things. Thus the board quickly becomes an essential tool for keeping track of the whole situation, along with some careful notes.

In one sense, Suspended feels visionary, or at least wholly unique in the Infocom canon. The standard text-adventure paradigm of play has been thrown overboard almost entirely. Gone, for example, is the need to map, along with the connection to a single in-game protagonist and any semblance of conventional storytelling. Further emphasizing the strategy-game feeling, Suspended is explicitly designed to be replayable. It has an “advanced” difficulty level you can attempt if you finally manage a good score on the standard, or you can choose the custom starting option, where you can choose the starting location of each robot and control when the various disasters are triggered. The manual suggests that you and friends could use this to “challenge each other” with new scenarios.

Unfortunately, the flexibility Suspended has can rather make us expect more from it than it can deliver. It would be nice if, like those board games I mentioned, Suspended could truly become a different experience every time it’s played by parceling out fortune and misfortune from a randomized deck of virtual cards. But alas, the same events will always occur even in custom mode; the only question is when, and even that is predetermined by the person entering the new parameters. Suspended upends the traditional Infocom approach enough that you wish it could have gone even further, dispensing with fixed puzzles and events entirely in favor of something completely dynamic and replayable. Maybe there’s a project in there somewhere for some modern author…

Visionary as it can feel, Suspended can also paradoxically feel like a bit of a throwback even in the context of its day. When we think of games in text today, we generally leap immediately to Adventure, Infocom, and all of their peers and antecedents. However, it’s important to remember that through the 1970s lots and lots of other sorts of games were implemented in text, simply because that was the only possibility. This included card games, strategy games, simulations, even action games. By the time of Suspended, the two text-only members of the trinity of 1977 (the TRS-80 and the Commodore PET) were fading away, and games other than adventures were expected to have graphics. One is almost tempted to look at Suspended as a text game that really wants to be in pictures, to imagine how cool it might be if the map board was included in the game itself as a graphical playing field. But then you realize that the very premise of having only one robot who can actually, you know, see is dependent on the proverbial magic of text, and a new appreciation for Berlyn’s creativity asserts itself. At any rate, it’s perhaps worth remembering again in light of Suspended‘s unusual mode of play that Infocom were not at this stage calling themselves makers of interactive fiction or even adventure games. They were just making games in text which were (they claimed) smarter and more sophisticated than those of anybody working in graphics.

Being such a departure from anything Infocom had done before (or, for that matter, would do later), Suspended pushed and stretched the ZIL system in unexpected new directions, turning development into quite a challenge. To make things harder, Berlyn, while he knew his way pretty well around an Apple II, had none of the grounding in programming and theory of the Infocom founders. Just getting him up to speed on ZIL took some time, and getting this extremely ambitious first project going took more. Yes, some of what was needed had been done already: Dave Lebling had first put together a system for passing orders to other characters for his own robot in Zork II, and Blank had made great strides toward a more dynamic model of adventuring in Deadline. Still, Blank had to work quite extensively with Berlyn to give him the tools he needed. A game of Suspended can have many, many balls in the air, with six robots all moving about following orders, disasters and events happening (or being averted) on the surface, and the player hopping about amidst all the chaos, taking in the scene through this robot’s senses, then issuing orders to that one. Further, the parser had to be substantially reworked to support it all; it’s now possible to issue orders to multiple robots at once, or even to tell two or more robots to work on something together, such as moving something neither one is strong enough to budge on its own. Taken just as a functioning virtual world, Suspended is damn impressive — amongst the most technically impressive worlds that Infocom would ever create.

It’s also damn difficult to penetrate. With its tersely sterile robotic diction, its ironclad adherence to the sensory limitations of each robot, and the time pressures of its cavalcade of disasters, there isn’t an ounce of compromise or compassion in the game. We can only take comfort in knowing that even in its cruelty it’s eminently fair, as uninterested in playing guess the verb or foisting illogical puzzles on us as it is in coddling us. There’s none of the sense here of a design that got away from its designer that plagues, say, the work of Scott Adams or the early work of Roberta Williams. Suspended is hard because it wants to be hard, and it’s hard in exactly the way it wants to be. Which isn’t to say that most players, myself included, are exactly disappointed that Infocom never ventured further down the trail it blazed. I suspect that Suspended is the Infocom game farthest away from the ideal of interactive fiction as it’s perceived and (in Infocom’s case) remembered today.

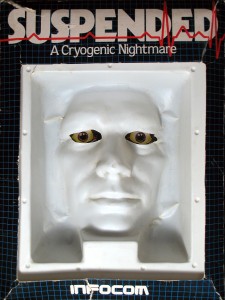

Suspended was released in March of 1983 in a huge and elaborate box (better to house that big laminated game board) that featured a recessed three-dimensional face mask for a lid. Surprisingly in light of the game’s difficulty and unabashedly experimental mode of play, it was yet another solid hit, selling some 55,000 copies in 1983 alone and eventually flirting with sales of 100,000 over its commercial lifetime. It really did seem that, at least for now, people were willing to follow Infocom wherever they led them. And Suspended was only the first release of 1983, the happiest, most financially successful year in the company’s history. I’ll have much more to tell about that year and the games it produced in the next posts.

(I’m thrilled to be able to say that since my last post on Infocom Activision has rereleased many of their games, including Suspended, for iPhone and iPad. If you don’t have an iDevice, you can certainly find the story file elsewhere on the Internet, but as usual I won’t be hosting it here. Just in case it’s helpful to anyone, here’s a very rough module for the VASSAL board-gaming engine with the Suspended map and counters. Load the save to position the robots as they are at the start of the standard game. If someone more familiar with VASSAL wants to clean it up and upload it to the official module repository, by all means feel free.

I should also note here that Marc Blank’s attitude toward the eternal game vs. story question that always hangs about Infocom and interactive fiction in general seems to have changed over the years. In an interview for Jason Scott’s Get Lamp documentary, he states that he always viewed Infocom’s works as fundamentally games rather than fiction or literature. In contemporary interviews, however, he often expresses the belief that Infocom was creating works that were different from — or, if you like, transcended — games. I believe his current thinking may be somewhat colored by the pain and frustration of Infocom’s later years, and his inability to really move the genre forward in a way that felt right to him.)