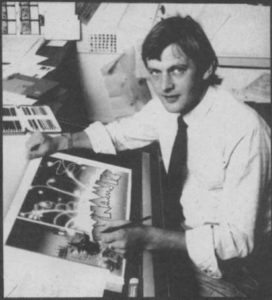

Ian Hetherington made for a strange choice as the guy to clean up Imagine Software’s confused finances. Brought in very late in the day to serve as the company’s financial director, he had no background in accounting whatsoever. Ironically, Bruce Everiss, who was serving as Imagine’s marketer and operations manager, had gone through an accounting program — yet he was, according at least to his own telling, always kept well away from that side of the business.

Hetherington, for his part, had worked at British Oxygen as a mainframe programmer before trying and failing a few times to get his own computer companies off the ground. The most recent and prominent of such efforts had been DAMS Business Computers, a partnership with DAMS International, a manufacturer of office furniture. The venture produced a number of hardware add-ons for the Commodore VIC-20 and 64 that added memory and features to the machines, but it never took off, and was wound up late in 1983 after lasting barely a year. It was at this point that Hetherington moved on to Imagine.

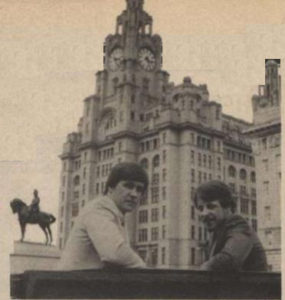

The trio who had run Imagine to this point were, with the possible partial exception of Everiss, a little in awe of Hetherington. Though he was a Liverpudlian like them, he came from a different social stratum; he was a polished, charismatic fellow whose public-school education helped him to talk a very good game indeed. Despite his checkered entrepreneurial career to date, he knew lots of people in the local business community, and knew in the broad sense how business worked — the very connections and competencies his new colleagues so conspicuously lacked. Indeed, it was likely his business connections, and the potential sources of desperately needed financing they could represent, that convinced the others in their naifish, literal-minded way to name him “financial director.” By this point, they were ready to clutch at any straw that might offer an exit from the mess they had created for themselves.

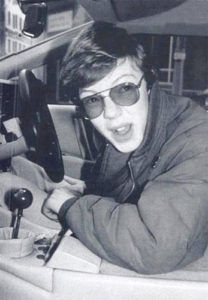

Of course, any hopes along those lines were doomed to be forlorn. No businessperson with an ounce of sense would invest in a company in Imagine’s state, no matter how silver a tongue Hetherington might possess. As we saw in my previous article, each of the principals dealt with the situation in his own way as the death spiral continued; the one consistency in their responses is a heaping helping of denial. Bruce Everiss tried to work his way out of the crisis, believing that if he stayed the course, showed up every day, and kept trying to get the megagames completed it must all work out in the end. (Such optimism may have had its roots in his lack of access to Imagine’s real finances.) All of the others simply checked out, spending less and less time at the office in proportion to Everiss’s increasingly long work week. Mark Butler, perhaps the most likable but certainly the most benighted of the group, adopted a “what I don’t see can’t hurt me” posture, spending his days out and about behind the handlebars of his racing motorcycle or behind the wheel of his BMW. Ian Hetherington and Dave Lawson also disappeared — but they, it would only slowly materialize, were busying themselves with something far more devious.

They made for an unlikely team. Initially, Hetherington, the smooth, cultivated businessman, hadn’t taken at all to Lawson, the plain-spoken Scouser. Hetherington may even have been moved once or twice to deploy the dreaded middle-class epithets of “common” and “peasant” to describe his working-class colleague. Over time, though, they bonded in a growing conviction that the ship of Imagine was going down, and that they didn’t want to go down with it. They would happily cede to Everiss the captain’s role; let him remain on the bridge until the bitter end.

Hetherington, being the more worldly of the pair, evidently came to the conclusion that the Imagine story could only end one way somewhat earlier than Lawson. When Paul Anderson of the BBC first came out to discuss making his television documentary about the company, probably in March or very early April of 1984, it was actually Lawson who carried the day for him, convincing his skeptical colleagues that the publicity was simply too great a chance to pass up. When cameras started to roll a few weeks later, however, both he and Hetherington wanted as little as possible to do with them. We can theorize, then, that reality hit home for Lawson at some point during those intervening weeks.

The plan Hetherington and Lawson were soon hatching was a bizarre combination of guile and naivete. They would form a new company, which they would name Finchspeed. They would quietly go about among the current Imagine staff, offering jobs to those they deemed both personally loyal to them and necessary to finish up the megagames, a total of about twenty people. This group would most definitely not include Everiss, whom both men by now openly loathed; the passive Mark Butler, on the other hand, was a question mark. Once they had the personnel lined up, they would transfer all rights and all ongoing work on the megagames to Finchspeed, leaving Imagine to crash and burn while they enjoyed that most precious thing in life or business: a second chance. So, that covers the guile. Where the naivete comes in, of course, is that neither life nor business usually makes it quite that easy to wash one’s hands of one’s past choices.

The pair did finally decide to include Butler in the conspiracy. The hard fact was that they needed his vote to go forward with the plan; Lawson owned just 45 percent of Imagine, with another 45 percent belonging to Butler and the other 10 percent to the deeply embittered Stephen Blower of the former Studio Sing, who could be expected to vote against anything proposed by the other shareholders as a matter of principle. Although Butler was fond of Everiss, Hetherington and Lawson believed — rightly, as it transpired — that he would be a fairly easy mark if given the choice between having a second chance as a software mogul or going back to selling computers in some shop somewhere. With the pliable Butler on board, they now had an overwhelming voting bloc for anything they might choose to do.

Before they did anything publicly, though, there was other secret business to take care of. Hetherington claimed he had investment contacts in the United States that would let Finchspeed raise £1.5 million to finish up the megagames and get them published. Therefore, after secretly forming Finchspeed and recruiting Butler and the other loyalists, Hetherington and Lawson flew across the Atlantic to try to secure the money. Thus they weren’t in the country for most of that fateful June of 1984, as the writs flew thick and fast and creditors pounded at Imagine’s door. Rumor back in Britain had it that they had fled the country in a panic, perhaps permanently; the real truth, as we’ve now seen, was far more devious.

One of those in the know inside Imagine finally leaked said real truth on June 29 — truly a bombshell of epic proportions for Bruce Everiss and everyone else remaining at the old company who hadn’t been invited to join the new one. An enraged Everiss walked out at midday, threatening all sorts of public consequences. Hoping to put a lid on the situation before it blew up in the press, Hetherington and Lawson rushed home from the United States the very next day. They hadn’t, needless to say, secured the financing Hetherington had so confidently predicted they would. He would later blame Everiss and the anonymous leaker of the bombshell for this failure, saying they had been about to seal a deal when forced to cut their trip short — truly an audacious attempt to play the aggrieved party, given the unconscionable dereliction of executive duties the pair’s leaving the country just as their company was collapsing represented.

Despite the lack of financing to see through their plans, on Sunday, July 1, hours after landing back in Britain, Hetherington and Lawson called an emergency meeting of the three-person Imagine board. Here they officially transferred the copyright on the megagames from Imagine to Finchspeed, who would also be allowed to use Imagine’s offices for free, for however long they still existed. In return, Finchspeed would need to pay Imagine £40,000 for the equipment they would use to develop the megagames, and would have to pay 50 percent of net profits from the games to Imagine after their release, up to a total of £625,000. These last stipulations may sound generous, but it should be remembered that Imagine was already a company well past the point of no return; as Hetherington and Lawson were in a position to know better than anyone, it was exceedingly unlikely that Imagine would still be around when any of the payments came due. Thus these stipulations were more about creating a veneer of plausible deniability than they were a good-faith business negotiation. After the entity that was Imagine no longer existed, Finchspeed could expect to walk away free and clear with the megagames.

Meanwhile Everiss was venting to anyone who would listen in the press, spawning an ongoing soap opera which the public could follow via magazines like Popular Computing Weekly and Home Computing Weekly. “They have set up Finchspeed in order to own Imagine’s megagames and assets for themselves,” Everiss said. “Ian Hetherington and Dave Lawson [were] in the States to raise funds for Finchspeed. Imagine will not see this money.” Everiss claimed that, incredibly, even the pair’s supposed partner Mark Butler hadn’t known they were going to the United States. “The only person they told,” he said, “was Andrew Sinclair [no relation to Clive Sinclair or the computer company of the same name], who basically is just David’s gopher, and Andrew had been spying on Mark and myself and reporting on a daily basis to them in San Francisco.” To add more fuel to the fire, Everiss noted that Hetherington and Lawson had taken their significant others with them to the United States, and claimed they had all traveled in high style, at a final cost of some £10,000 that was charged not to Finchspeed but to Imagine — presumably in the expectation that the whole trip could be written off once the latter went bankrupt.

Hetherington and Lawson’s defense was, to say the least, unconvincing. Speaking from the United States on June 29, Hetherington had claimed that “Dave Lawson and myself have been in Silicon Valley to try to raise money for Imagine for the last two weeks. We set up Finchspeed as an off-the-shelf company to get money into Imagine. There is no point in discussing Finchspeed since it is dead and burned. It’s forgotten.” But if it was “dead and burned,” why were they suddenly transferring Imagine assets to Finchspeed two days later? Hetherington said that “it is important that the megagames go out with Imagine’s name on them, and I will do anything to ensure that they do.” Did that “anything” for some reason need to include transferring their copyrights to another company? At least one of his comments, at any rate, rang true for anyone who was aware of the petty infighting that had been going on for the past several months inside Imagine: “Staff will have to be sacked who are now loyal to Bruce Everiss.”

In the end, this attempt to pull a fast one, like just about everything anyone at Imagine ever touched, turned into an embarrassing failure. When hatching the scheme, Hetherington and Lawson had neglected one stipulation of the law: that any contract entered into by a company that already had a “winding-up” petition filed against it — which Imagine had had since April — could be set aside by the liquidator after said company is declared bankrupt. The law, in other words, had already foreseen the possibility of bright young sparks attempting exactly what Hetherington and Lawson had been trying to do, and had made provisions to prevent it.

It was announced in August that the arrangement between Imagine and Finchspeed dating from July 1 was null and void on these grounds. The megagames, like all of Imagine’s other assets, passed to the liquidator for disposition in whatever manner would most benefit Imagine’s creditors. Dave Lawson, in the face of all the evidence to the contrary, tried to claim this had been understood all along: “There was never any doubt that the megagames were with Imagine’s receivers because the contract between the two companies was not honored.” And again, it wasn’t entirely clear what some of these words were supposed to mean. In what way was the contract “not honored?”

But still the pair refused to give up on their dogged pursuit of the megagames. Whatever else one can say about their business ethics or lack thereof, it’s clear they were deeply, genuinely passionate about the concept, and so attached to it that they were willing to expend enormous effort trying to finish what they had started at Imagine.

In light of such passion, the question of what the megagame concept actually was arises yet again. As I noted last time it reared its head, that was always very difficult to say. Perhaps the best description of the megagame dream was ironically provided by Hetherington and Lawson’s arch-enemy Bruce Everiss, many months after the Imagine collapse. He made them sound much like the “interactive movies” that would soon become the signature products of the American publisher Cinemaware, describing them as a “film which you, the player, take part in”:

You become one of the cast of characters that each have separate and identifiable personalities. What happens when you meet them depends on their personalities and also on what you do, as in real life. Characters then remember how they have been treated by the player and act accordingly on subsequent meetings.

There are no lives or score. It is a matter of trying to achieve what you, the player, wants. There is no status line to ruin the realism. The whole screen is action.

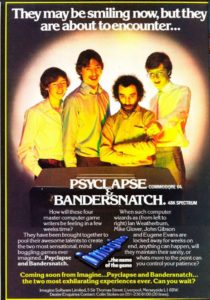

The Commercial Breaks episode dealing with Imagine included a brief, tantalizing glimpse of Bandersnatch, the first of the megagames, in action, and it did indeed seem to conform to this rough description.

Hetherington and Lawson’s hopes of reviving the megagames were given new life when word went through the industry that Sinclair Research was interested in funding and publishing software for their new QL computer. The QL had made its debut at the beginning of 1984, the first machine available to British users that was built around the powerful new Motorola 68000 processor line instead of the old 6502 or Z80. Unfortunately, it was able to beat the competition to the market only through being released months before it ought to have been, with both hardware and operating system still in a shabby, untested state. Sinclair had been struggling ever since to rehabilitate the machine’s image. One way to reverse the QL’s fortunes, they decided, would be to make it play games that would never be possible on a Spectrum. By way of getting that ball rolling, they were ready to fund a number of such projects and then publish the results themselves. [1]One other company to benefit from their largess would be the text-adventure maker Magnetic Scrolls; Sinclair would wind up funding much of the development of their in-house adventure system, and would publish The Pawn, the first game made using it, first for the QL.

There was a certain synergy here which it didn’t take Hetherington and Lawson long to spot. The megagames had needed to add new hardware to the Spectrum because they would have been too big and ambitious to contemplate otherwise. That, anyway, had been the old Imagine company line. Now, much the same argument could be used to justify porting them to the QL, without all the complications of the hardware add-on they had planned for the Spectrum version; the QL had 128 K of memory, more than the Spectrum’s 48 K of internal memory and the 64 K of the proposed hardware add-on combined. The advertising practically wrote itself: the megagames are made possible only by the 16-bit power of the QL!

The tireless Ian Hetherington worked out an arrangement and got Sinclair to agree to it. First, Sinclair bought the rights to the megagames at the liquidation auction; these cost them the princely sum of £700, plus a stipulation that Imagine’s creditors be paid a portion of any income they might eventually generate. Then, Hetherington and Lawson and a handful of their loyalists from Imagine set up yet another company, for the older Finchspeed was too beset with questions, too mired in the scandal of the Imagine collapse to continue with — and then there was also the problem of the now-superfluous Mark Butler, who had been given a third of Finchspeed; he would be cut out of the new company, thus ending his brief but colorful career in games.

Hetherington and Lawson’s latest company was named Fireiron. The day it was formed, Sinclair signed a contract with its owners, paying them to port the megagames-in-progress to the QL and then to finish them off on the new platform.

So, Hetherington and Lawson were seemingly back in business, picking up where Imagine had left off. This included, unfortunately, the same tendency toward wildly overambitious pronouncements. “Originally at Imagine we were working on seven megagame titles,” said Lawson. “I see no reason why we shouldn’t continue with them all.” In reality, only two megagames had progressed far enough to have titles, and only one, Bandersnatch, had had significant programming done. Given these realities, it was perhaps dangerous to trust too much in Lawson’s assertion that the old Speccy version of Bandersnatch was “90 per cent complete,” and could be ported to the QL and completed there in very short order. Still, the new arrangement didn’t seem a bad one, all told. There was even something in it for Imagine’s long-suffering creditors, should the megagames prove successful.

Of course, all of Hetherington and Lawson’s efforts were still dogged by the sorry collapse of Imagine, and the less than standup way they’d responded to it. Judging a good offense to be the best defense, Hetherington took to calling up the most aggressive journalists to throw a mixture of bluster and threats of libel suits back in their faces. He was, he said, “sick to death of people insinuating that anything untoward happened at Imagine.” Sometimes his efforts could lead to uncomfortable juxtapositions, as when he called Crash magazine to push back against a lengthy article on the Imagine collapse they were planning to run, only to be connected with the accounting department, who were more interested in finding out whether the magazine stood any chance of ever being paid for the £5825 advertising bill that the bankrupt Imagine still had outstanding.

For understandable reasons, Hetherington and Lawson wanted more than anything to put the whole Imagine debacle behind them and focus on the future. Ian Hetherington in January of 1985:

My attitude has always been that it’s all over now, and what we’ll do is quickly get our lives back together again. I don’t want people bringing back something that happened six or seven months ago. What we’re doing now, Dave and I, is improving on megagames to produce something quite startling. We want to bow out at the top.

The many creditors who had had faith in Imagine, only to be bilked out of many thousands of pounds — not to mention the many dozens of employees who had lost their jobs — weren’t quite so willing to declare the events of just six months previous to be ancient history. “The lying and deception” Hetherington and Lawson had engaged in, Bruce Everiss said, “were almost boundless.” Assuming he was correct, it certainly did seem like those actions ought to have consequences. Still, there was only so much outrage to be generated; the scandal of Imagine did gradually fade into the past, giving at last to Hetherington and Lawson the fresh start they looked for.

Yet their new life as Fireiron showed every initial sign of following the same pattern as their old one with Imagine. Relations with Sinclair steadily worsened in 1985, with the latter claiming Fireiron was spending far too much of their money in the course of missing deadline after deadline. The original plan had been to release Bandersnatch in the first quarter of 1985, a goal that would most definitely not be met. Meanwhile the Sinclair QL’s position in the marketplace was going from bad to worse, such that it seemed highly unlikely that Bandersnatch or anything else could save the machine. Sinclair unceremoniously dropped Fireiron in the spring of 1985.

But still Hetherington and Lawson refused to give up on their megagames. They hatched yet another scheme, this time to port Bandersnatch to the new Atari ST computer, a machine based on the same 68000 architecture as the Sinclair QL — thus making the task of porting the work-in-progress QL version to it dramatically easier — but one which looked to have a much brighter future. The only problem was that Sinclair still owned the copyrights to the megagames. To get around that issue, Fireiron simply renamed Bandersnatch to Brataccas and dropped the old “megagame” buzzword entirely. (Good riddance, said an exhausted industry!) This move introduced all sorts of new legal jeopardy for the Fireiron folks, but they were fortunate in that Sinclair, who would soon sell off their entire extant computer business to Amstrad, never seemed to pay enough attention to realize what Fireiron had done. Ditto the Imagine liquidators and the creditors, who would no longer be receiving their cut of any royalties the rechristened megagame might generate.

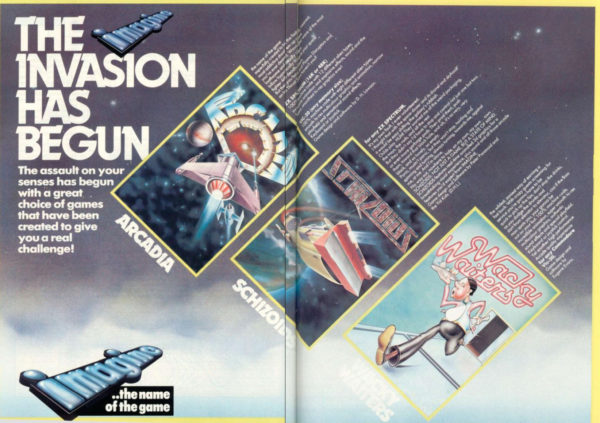

In lieu of Sinclair, Hetherington was able to scare up some alternate financing, this time from one Richard Talbot Smith, a big wheel in the world of Liverpool business, owner of the only steel foundry and the only Mercedes dealership in the city among other ventures. Also coming aboard at this time, perhaps at Smith’s insistence, was an experienced businessman named Jonathan Ellis, who could hopefully serve as the steady hand at the wheel in terms of finances and day-to-day operations that Imagine had never had. The company got yet another new name in the process of making these changes, this one destined to stick. When the rejiggered Fireiron brought a prototype of the Atari ST Brataccas to the Personal Computer World Show in September of 1985, they did so as Psygnosis. The name, according to Hetherington, “just happened.” Beyond the obvious echoes of Psyclapse, the planned second megagame from the old Imagine days, the only clear logic behind the made-up word was an intimation of “knowledge of the mind” in badly garbled Greek.

Roger Dean’s iconic Psygnosis owl logo, one of the most immediately recognizable in the games industry.

Having earlier made a deal as Imagine with the well-known pop artist Roger Dean, only to see it collapse along with the rest of the company, the new Psygnosis now reached out to him again for help in crafting their visual identity. “They kept throwing names at me, and wanted something that said ‘knowledge,’ ‘the future,’ ‘wisdom,’ and ‘fun,'” Dean remembers. What he came up with in response was one of the more enduring logos in videogame history: a slightly robotic-looking owl, rendered in his trademark airbrushed style. It seemed, to him anyway, a perfect representation of “knowledge,” “the future,” and “wisdom”; as for fun, it was after all to be attached to games, so presumably that would be self-evident.

In a way, it was starting to feel like old times again, with the old hype machine once again kicking in. Brataccas was given pride of place inside Atari’s own booth at the Personal Computer World Show, running on four screens in order to be sure it wasn’t missed. Even Eugene Evans was there, hired by Psygnosis to serve as a temporary spokesman, doing the charming PR thing he had always been so good at as smoothly as ever. Rumor had it that even Bruce Everiss had been seen skulking about the Atari booth with a sour expression on his face.

That said, life at Psygnosis wasn’t quite all it had been at Imagine. The company’s new offices, located in a disused warehouse behind Roger Talbot Smith’s steel foundry in the midst of Liverpool’s downtrodden dock district, were a far cry from the old digs. One former employee describes the setting as “a dirty part of town,” remembering how he’d return to his car every evening at quitting time to find it covered in the “crap” spewed by the foundry’s smokestacks. Speaking of cars: the Ferraris, BMWs, and Porsches that had been the company cars at Imagine had been replaced by a fleet of Vauxhall Cavaliers. But Hetherington and Lawson’s megagame dream was still alive, even if it could no longer be described using that word. Against all the odds, it looked like they might just manage to finish Bandersnatch — woops, Brataccas.

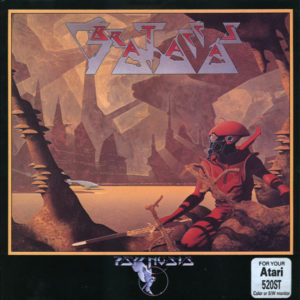

Brataccas for the Atari ST shipped in the first week of 1986 in an elaborate oversized box painted by Roger Dean. Hetherington and Lawson had kept the faith through two years of hype and rumor and scandal and conspiracy, through four separate company names, had violated ethical norm after ethical norm in order to reach this fruition of the megagame dream. With a buildup like that, the end result was perhaps doomed to smack at least a little of anticlimax.

What was surprising, however, was just how thorough the anticlimax was. There was no kind way to put it: Brataccas was a hot mess. The unabashedly high-concept game attempted, as its billing had always suggested it would, to be a genuinely new, more dynamic and emergent approach to an adventure game, including context-sensitive conversations and action-oriented combat. Sadly, though, it was just about unplayable. The control scheme was based on mouse gestures; in this it was, like so much about the legacy of Imagine, ahead of its time in conception but atrocious in execution, making things the game seemed to expect you to do with relative ease all but impossible. This alleged animated adventure turned into a slideshow every time other characters were on the screen — if it ran like this on the 68000-based Atari ST, one shuddered to think how it would have performed on the 8-bit Speccy! — and the design of the puzzles and other adventurey bits were even worse than one might have expected from a development team that had never made an adventure game before and had never thought deeply about how to make a playable one. It was impossible to know how to even begin the task of solving the quest, impossible to know what the game really expected of you. And, despite or because of all the time spent in development on all those different platforms, it was horrendously buggy to boot. Even the graphics, in marked contrast to the Psygnosis games that would follow it, weren’t much to write home about.

A cynical observer of Imagine’s history would have said before the release of Brataccas that it was doomed to be a disaster, that no one at the company had ever demonstrated the ability to pull off a concept like this one — and, it was now clear, said cynical observer would have been exactly right. Computer and Video Games magazine wrote that Brataccas “still bore all the scars of its unenviable pedigree. Brataccas is definitely a game whose origins are more interesting than the end product.” Oh, well… Roger Dean’s box sure looked nice.

“A space fugitive walks into a bar….” The unique thing about Brataccas in contrast to contemporary adventure games is its dynamic nature, its focus on simulation. In other words, the young lady whom our hero appears to be chatting up actually will go to Calypso foyer. It’s only a shame that it’s all executed so poorly.

Brataccas’s one saving grace was timing. It hit the market at a time when few games were yet available for the Atari ST, and most of those were ports of older 8-bit titles. Despite its own 8-bit origins, Brataccas was, whatever else one said about it, something unique, something you couldn’t play on a Spectrum, a Commodore 64, or a BBC Micro. This factor drove what modest sales the game was able to rack up on the Atari ST, as it also did sales of the Commodore Amiga version which appeared shortly thereafter. The same factor helped Psygnosis set up distribution to North America through a deal with the publisher Mindscape — something Imagine, notwithstanding their stated goal of becoming the preeminent name in computer games “throughout the world,” had never managed.

Still, the “success” of Brataccas, dwarfed as was the game itself by all the hype that had surrounded it for so long now, based more on historical happenstance than the game’s intrinsic qualities, didn’t portend a stable, prosperous, or for that matter lengthy future for the company that had made it. Our aforementioned cynical observer doubtless wouldn’t have hesitated to note this reality as well. In this case, though, the observer would be unexpectedly proved wrong. Psygnosis was about to make a pivot from such high-concept fare as Brataccas to something else entirely. And in doing so, Ian Hetherington and Dave Lawson, along with their new partner Jonathan Ellis, would evince a rare and precious quality, one that few would have dreamed that they had in them based on their record to date: they would demonstrate an ability to change.

(Sources: the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Videogames Conquered the World by Rebecca Levene and Magnus Anderson; Popular Computing Weekly of April 7 1983, July 5 1984, August 16 1984, September 27 1984, October 11 1984, and September 19 1985; Commodore User of June 1983; Home Computing Weekly of July 17 1984; Your Computer of January 1985 and October 1985; Sinclair User of October 1984; Personal Computer Games of September 1984; ZX Computing of February/March 1985; Crash of January 1985, February 1985, and October 1985; Computer and Video Games of August 1986; The One of May 1991; Retro Gamer 50; the online articles “From Lemmings to Wipeout: How Ian Hetherington Incubated Gaming Success” from Polygon, “Dams Double at Nemo” from Channel Info, and “The Psygnosis Story: John White, Director of Software” from Edge Online.)