If traditional film is a river, the viewer of that film sits on the bank and watches the water flow by. We wanted to take that viewer and turn them into a fish and put them down into that river.

— Greg Roach, Director of The X-Files Game

Given the demographics of X-Files fandom, we probably shouldn’t be surprised that the show’s parent network Fox started to think about making a computer game that was officially based on it quite quickly. Already early in the second season, before the big breakthrough at the Golden Globe Awards, Fox began making inquiries on the subject with game developers. This was the peak of the interactive-movie era, when games that blended interactivity with video clips starring real human actors were widely believed to be the necessary future of the medium. Fox’s search thus led it to HyperBole Studios, a company whose name positively screams 1990s — note the sticky capital “B” in the middle of it — every bit as much as The X-Files itself. With a name like that, how could the studio be anything but a loud and proud advocate of the so-called “Siliwood” approach to game making?

HyperBole had actually been around for half a decade by that point, evolving alongside the hype over multimedia computing. It was the brainchild of one Greg Roach, who had gotten his first Apple IIc home computer in 1985, when he was still a university student majoring in theater and philosophy in Houston, Texas. He had tried to play the text adventures of the era, but found that they didn’t agree with him. What should have been “portals to a different world” struck him as balky, pedantic, and dull.

A few years later, when he was employed as an associate director at the Stages Repertory Theatre in Houston, he got his first glimpse of HyperCard on the Apple Macintosh. It was a revelation. “Here was the answer I’d been looking for,” he says. Like a lot of other starstruck HyperCard zealots from unusual, often non-technical backgrounds, he founded a company to bring his hypertext experiments to the world. Initially, he did not envision HyperBole as anything so gauche as a games studio: it was rather to be the publisher of a bimonthly multimedia magazine on two floppy disks. The magazine never quite met that bimonthly schedule, but Roach and his friends did manage to put out nine issues between 1990 and 1992. Each was an eclectic mix of hypertext narratives, comics, visual art, video clips, poetry, and opinion pieces. “The writing can sometimes be a little idiosyncratic,” wrote MacUser of the endeavor, “but it’s never boring.” The magazine’s most ambitious project was The Madness of Roland, an “interactive novel” by Roach himself that ran in installments in the first six issues. Sprouting from The Song of Roland, the towering Medieval epic about a chivalrous knight-errant in the time of Charlemagne, it quickly evolved — or devolved, depending on your point of view — into a stream-of-consciousness postmodern pastiche of the sort that was very popular among academic hypertext theorists at the time. It was eventually released in an enhanced version as a standalone product.

The hard truth was, however, that work like this was more interesting to the literary theorists than it was to ordinary computer owners; you certainly weren’t going to be able to sustain a software company of any real size on it, not even one that catered to the artsy, well-heeled Mac user base. Being a man with commercial as well as intellectual aspirations, Roach decided to add the revolutionary new storage medium of CD-ROM to his technological stack and replace interactive books with interactive movies. He ended the magazine and moved to Seattle, both to be closer to the West Coast tech titans and to take advantage of the city’s underrated theater and film- and video-production communities. No shrinking violet, he branded himself “the Spielberg of multimedia” and “a theorist of virtual cinema,” and commenced cold-calling anyone who would pick up the telephone. For example, he talked his way into sharing a stage with Sid Meier for a debate over “Multimedia versus Game Design” at the 1994 Computer Game Developers Conference, where he discussed the importance of things like “a geometric understanding of the spatial possibilities of what the media represents.” (Such tangled phraseology left Meier scratching his head; he kept trying to bring the conversation back around to the best ways of making games that were, you know, fun.)

Roach charmed enough venture capitalists to hire some programmers, who helped him to create a system for making interactive movies called, naturally enough, VirtualCinema. In another tribute to his energy and persuasiveness, HyperBole became the first games studio to be signed by Hollywood’s Agency for the Performing Arts — the most prestigious talent agency in Tinseltown — as a client.

The first of HyperBole’s VirtualCinema games was one of the last to be published by a shady outfit called Media Vision, which had gotten its start in sound cards and was now attempting to build a larger empire on boxed games of its own and, wherever and whenever these failed to deliver the goods, lots and lots of accounting fraud. According to Roach — admittedly, not always the most reliable witness — Media Vision yanked a half-completed interactive movie out of his hands and rushed it onto store shelves when the financial house of cards began to show signs of instability. Be that as it may, the game called Quantum Gate was followed just nine months later by one called The Vortex: Quantum Gate II that picked up right where it had left off. By that time, however, the house of cards at Media Vision had collapsed, so the sequel was published by HyperBole themselves. As a result, it had little retail presence and sold hardly any copies at all.

If nothing else, these games served to prove the wisdom of the move to Seattle; in terms of their acting performances and overall production values, they really did stand out from most of the sub-B-movie competition in their space. Unfortunately, Roach’s scripts were less impressive, being a nearly incomprehensible mishmash of science-fiction clichés and New Age malarkey. The interactivity wasn’t up to much either: just some deserted corridors to wander from a Myst-style first-person perspective, some menus that popped up in conversations but made minimal difference to the larger arc of the story, and, most lamentably and inexplicably of all, a thoroughly botched attempt to re-implement the old arcade classic Battlezone.

Despite their shortcomings, the Quantum Gate games wound up serving HyperBole well after a fashion. For when Fox started looking around for someone to make an X-Files game, HyperBole’s Hollywood talent agency could submit them as demo reels. Roach claimed in 1998 that, upon being formally invited to submit a bid for the project, he almost turned the opportunity down: “I’d never seen The X-Files at that point. But then I watched the show. The creative possibilities were intriguing, so we went back to Fox and affirmed our interest.”

It soon became clear that the idea of an X-Files game was being driven by the suits at Fox, not by the team that was in the trenches making the television show from week to week. Chris Carter was at best ambivalent. “What can you do that I can’t?” he asked Roach at their first meeting. Slowly, Roach talked him around, at the same time that he convinced his bosses at Fox that the VirtualCinema engine was just the tool for the job. Eventually, Carter agreed to provide a story outline which HyperBole would then turn into a game. By the end of 1995, when the show was in the midst of its third season, the deal was done. Barely three years removed from making an underground multimedia magazine in his basement for a few hundred subscribers, Roach was now to be entrusted with one of the hottest properties on television, watched by tens of millions of people every week. Truly these were strange times in gaming.

That said, it wasn’t going to be practical to build the entire game around Mulder and Scully; David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson were busy enough as it was. At the same time, though, any alleged X-Files game from which they were completely absent would surely be pilloried. Carter’s story outline rather cleverly solved the problem by giving the player control of another, newly introduced FBI agent by the name of Craig Willmore, who would be set on the trail of the usual twosome after they mysteriously disappeared in the middle of an investigation. Duchovny and Anderson would appear only near the end of the game, as the player’s reward for getting that far. All things considered, it seemed like a reasonable compromise.

After much fraught negotiations with the two stars’ representatives, it was agreed that they would come to Seattle for about a week to film their scenes. Mitch Pileggi, who played Assistant Director Walter Skinner, Mulder and Scully’s immediate superior at the FBI, signed on as well. Ditto the actors who played The Lone Gunmen, a trio of eccentric computer hackers who helped Mulder and Scully out from time to time on the show. Even William B. Davis, otherwise known as Cancer Man, agreed to a cameo appearance.

Getting all of this arranged took months and months. “Working with a company like Fox is a lot like talking to a person with multiple-personality disorder or Alzheimer’s,” says Roach. “They never remember from one minute to the next what they’ve agreed to. We had to deal with the legal division, marketing department, Fox Interactive, the TV division, and Chris Carter. Each of them has their own fiefdom and their own veto capacity that only extends so far in certain areas.” Most creative decisions required the approval of Carter, but it was made all too clear by his average response time to queries that the X-Files game was not high on his priority list. In all, another year and a half went by before the design document, script, and all of the assorted acting contracts were far enough along that shooting could begin.

This milestone coincided with the end of the show’s fourth season, when it was nearing the absolute pinnacle of its popularity and cultural cachet. A typical 24-episode season was shot at a pace of roughly one episode every ten days, meaning that Duchovny and Anderson could expect to spend a good two-thirds of each year playing Mulder and Scully. This year they were even busier, however, because an X-Files feature film was to be shot between the fourth and fifth seasons, to premiere in movie theaters right after the latter had finished airing. And on top of all this, the two were now expected to come to Seattle during the two-week gap between the fourth-season wrap party and the beginning of work on the film in order to help Greg Roach get his computer game done. Understandably enough under the circumstances, they arrived tired and decidedly unenthusiastic. Because of the scheduling issues, Mulder and Scully’s scenes were to be filmed first — a true baptism by fire for the cast and crew. “After that, the rest of the shoot seemed relatively easy,” says Roach.

Duchovny, who had aspirations of becoming a Hollywood leading man of the sort who could carry a major non-X-Files film on his own, had been growing restless on the television show of late. It isn’t hard to imagine what he thought of the notion of appearing in a videogame, a still less respected medium than television. HyperBole did their best to make him happy, even going so far as to place a private yoga instructor at his beck and call throughout his stay in Seattle. Nonetheless, he did the bare minimum required of him during the time he was contractually obligated to make himself available, then jetted off without a backward glance to enjoy what was left of his holiday.

Gillian Anderson, on the other hand, went above and beyond the call of duty. Once the concept of the game was explained to her, she became genuinely interested in what HyperBole was trying to do, and put in a lot more effort than she needed to. She even agreed to stay on a few extra days after Duchovny left, to shoot some extra scenes that Greg Roach hastily wrote to take advantage of her unexpected graciousness. “I like the Four Seasons hotel in Seattle,” she said as a way of deflecting everyone’s gratitude. If you’ve played the game, you probably noticed that you see a lot more of Scully in it than Mulder. Now you know why.

The entirety of the filming took seven weeks, all of them spent at locations in and around Seattle. A goodly chunk of the crew’s time was spent at the old Naval Station Puget Sound at Sand Point, a Navy base and airfield — the first airborne circumnavigation of the Earth had ended there in 1924 — that had recently been decommissioned as part of the peace dividend for winning the Cold War. It was in every way a classic X-Files set. “It had to be big, it had to be scary, it had to be a Byzantine maze with corridors and machinery,” says Roach. “At Sand Point, they’d built a new brig, and then a year later the base was shut down. So we had this huge, brand spanking new, governmental, high-tech facility that provided the perfect shell for the secret base.” The local maritime training academy and its primary training ship, formerly an ocean-going icebreaker and tug, were more thoroughly X-Files-looking places. All were shown to maximum advantage, thanks not least to Director of Photography Jon Joffin, who had held the same title for eleven episodes of the television show during its fourth season. He became known as “the smoke Nazi” around HyperBole for his ability to conjure up that trademark X-Files murk.

Once the filming wrapped, it was back to the office for the HyperBole principals. There they used the VirtualCinema system to turn the video footage that had been shot, along with still photographs of the various locations, into a game. As this work proceeded and the likely timeline for its completion firmed up, Fox decided how to incorporate the game into its marketing plans for The X-Files in general. The summer of 1998 was already to be The Summer of The X-Files; a shocking, bravura finale to the fifth season on May 17 would lead right into the movie hitting theaters on June 19. The game seemed a nice adjunct to these plans; indeed, it was decided that it should be released on the very same day as the movie’s premiere. To emphasize its kinship with what most people were calling “the X-Files movie” — its official name was just The X-Files — Fox Interactive branded HyperBole’s effort simply The X-Files Game, which was certainly descriptive if not very original.

Gillian Anderson further endeared herself to Fox Interactive and HyperBole by agreeing to come to the E3 trade show in May of 1998 to sign autographs and promote the soon-to-be-released game.

When June 19 arrived, those eager fans who stopped by a software store on their way to or from their friendly local movieplex got, alongside more X-Files than was probably good for anyone in such a compressed span of time, a game that was exceptional in some ways but ultimately unable to overcome the limitations of its format. By 1998, those limitations were already causing the games industry to move sharply away from the interactive-movie conceit and all it entailed. The appearance of The X-Files Game this late in the day was more a tribute to its long gestation time and the power of licensing than any strong demand for more games of this type in the marketplace. In fact, The X-Files Game was the very last splashy production of its kind to hit store shelves, the last gasp of a confused but earnest movement in game development that really had once seemed like the future of the medium writ large. (Three other stragglers of the same breed — The Journeyman Project 3, Black Dahlia, and Tex Murphy: Overseer — had shown up earlier in 1998.) Game developers like Greg Roach and HyperBole, who had irrevocably married themselves to the idea of a grand alliance between Silicon Valley and Hollywood, would find themselves out of a job going forward. One can only hope that it was fun for them while it lasted.

As the last of its kind, The X-Files Game ought to be an exceptional example, the highest iteration of the interactive-movie conception. And in some ways at least, it really is. It sprawls across no fewer than seven CDs. That space is used for video that looks far better than the norm — almost, dare I say it, of DVD quality.

The live-action segments also impress in ways that transcend mere audiovisual fidelity. Their production values are superb by comparison with almost any other interactive movie. They make no use of green-screening: the practice of painting pixel-arts “sets” in behind human actors who have said their lines on empty sound stages, an approach which was used in the vast majority of other games of this type because it was much, much cheaper than filming on proper sets. Roach claims that it cost $6 million in the final reckoning to make The X-Files Game. A good chunk of the budget was doubtless swallowed up by the complicated corporate logistics of the project; David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson would soon be signing contract extensions on the television show that paid them six-digit sums for every single episode they appeared in, and one has to assume the salaries they were paid to appear here were comparable if not even more excessive. Still, there’s no denying that this game looks as good as any typical episode of the show. It genuinely feels like The X-Files. Of course, it helped to shoot in Seattle, a city whose climate is much the same as that of gray-and-rainy Vancouver, its neighbor just on the other side of the border to its north.

The acting here acquits itself reasonably well too. Yes, Duchovny looks a little bored and irritated, but Anderson is fine in a role whose tics and mannerisms she has down flat, as is Mitch Pileggi. The unfamiliar actors who are expected to carry the balance of the game don’t do much if any worse than your typical guest star on the show. Jordan Lee Williams, who plays Agent Craig Willmore, carries out his ersatz Mulder assignment about as well as one can ask. Ditto Paige Witte, who plays the Seattle police detective who becomes Willmore’s partner in investigation, his equivalent of Scully.

Alas, the part of The X-Files Game that is supposed to put the “interactive” in an interactive movie is less impressive and more problematic. Before I get to that, though, I do need to note that one accusation which has been repeatedly leveled against this game from just after its release right up until the present day actually isn’t fair at all. When you first arrive at the Seattle FBI office as Agent Willmore, you need to log into your computer, which in turns requires a password. Lackadaisical reviewers have been writing for decades now that you’re expected to guess this password from Willmore’s enthusiasm for the history of the American Civil War and a whole lot of lateral thinking. This would indeed be an awful puzzle to start (or end) any game with, not to mention nonsensical in terms of verisimilitude. (You’re supposed to be Willmore, after all. Why would he need to puzzle out his own password?) But it’s not a puzzle: the password you need is written in the manual. The fact that this caused such confusion is itself a sign of changing times in gaming. Just a few years before The X-Files Game, gamers were poring over manuals as a matter of course; by a few years after, manuals had all but disappeared. This game found itself caught in the middle, making assumptions about its player base that no longer held true.

In reality, the problems here don’t come down to nonsensical puzzles. Greg Roach never had much interest in puzzles anyway, and, even if he would have, Fox had made it clear that this product must be accessible to people who had never played a computer game before, who were attracted strictly by the name of the television show on the box. All of which means that, although The X-Files Game plays superficially like a Myst clone when you aren’t watching video clips or clicking through dialog trees, it can’t offer up the usual array of arbitrary set-piece puzzles to gate your progress. And that’s a fine, even welcome development in itself; Lord knows, we had all seen enough slider puzzles to last a lifetime by this point. Yet it gradually becomes clear that neither Roach nor anyone else at HyperBole has anything to hand with which to replace arbitrary puzzles. This investigation turns out to require shockingly little thought on your part. Go where the game wants you to go and click on everything there. Rinse and repeat, and in due course you win.

Now, even this isn’t awful in itself. There is plenty of room in my heart for a game that’s not really interested in challenging me, that just wants to sweep me away on the wings of an exciting story. But there are two more downfalls here. One has a remedy; sadly, the other does not.

The first is the “clicking on everything” part of the equation. The X-Files Game may have decided to abandon arbitrary puzzles and to replace pre-rendered 3D scenes with carefully shot photographs, but it still has all the other infelicities of the Myst-style first-person, node-based approach to navigation. You never know quite where all you can look, and your degree of rotation when you turn is wildly inconsistent from node to node. It’s disarmingly easy to get confused just trying to weave your way through the FBI office. And when the game sends you off to a sprawling warehouse with darkened nooks and crannies everywhere… oh, my. Here you have to scour every single node and viewpoint for the tiny pieces of evidence that you need to collect to jog the plot wheels back into motion. There’s nothing fun about this. It makes the game hard in the most annoying of all possible ways; I’ll take slider puzzles any day over fake mazes and pixel hunts.

Thankfully, the game does give you a way of avoiding most of these stumbling blocks. You can turn on something called “Artificial Intuition” to gain access to a hint system and, most importantly, activate an icon that will swirl suggestively whenever you’re “in close proximity to information vital to the investigation.” I advise you to spare yourself a world of frustration by taking advantage of it.

But my other overarching complaint has no similar remedy. It goes to the story itself, which is… well, it’s just not that good, certainly not good enough to maintain the player’s interest in the absence of compelling gameplay. Greg Roach’s script from Chris Carter’s story outline is most kindly described as workmanlike — X-Files by the numbers, without the flashes of subversive wit and human warmth that marked the television series’s best episodes.

There are linchpins of the plot that just don’t make much sense. When you finally locate Scully, you learn that she’s been cooling her heels for several days in a sanitarium — a perfectly innocent one, that is, not the type you can’t check out of — without bothering to tell anyone at the FBI where she is. Meanwhile Mulder has gone charging off on the trail of yet another government conspiracy involving aliens without ever bothering to tell his partner what he’s up to, much less the agency that employs him. Even by the usual standards of these two, that’s some terrible communication.

Other weaknesses are inherent to the very nature of the project. The X-Files Game was always destined to be a bit player in the larger X-Files saga. The “Mulder and Scully have been kidnapped!” plot tries its best to get you invested, but these are, after all, the two most incompetent agents at the FBI, who rush heedlessly into danger and nearly get themselves killed every single week. We know perfectly well the game isn’t going to let them die, as we also know that nothing all that important to the larger mythology of the show is going to be revealed by this ancillary production. The stakes never feel very high because we’ve seen all of this so many times before. In the X-Files movie, Scully is kidnapped and Mulder must effect a rescue; once you find Scully here, it becomes a mirror image of that scenario. And so, as Joni Mitchell sang, it’s “round and round and round in the circle game.”

The date which appears onscreen at the opening of the game places it in the past of the current X-Files chronology at the time the game was released: all the way back in the third season, which was, not coincidentally, the season during which Chris Carter wrote the story outline. At that time, the mythology episodes were revolving around the “black oil,” a kind of parasitic alien consciousness that could infect human hosts and take them over, Invasion of the Body Snatchers-style. But that plot line had long since been put to bed by the time the fifth season rolled around, the better to make way for the latest existential threat to humanity. Here, however, we’re mired in the stuff once again, in a way that must have felt painfully anticlimactic to those hardcore X-Files fans who rushed out to pick up the game upon its release.

In lieu of a plot that goes anywhere particularly interesting, the script dangles the promise of meeting Mulder and Scully in the flesh as the most tangible reward for slogging through the mazes and pixel hunts. From a certain perspective, this was clever. But it doesn’t do anything to make The X-Files Game a game that can stand on its own, divorced from the television show that spawned it. Quite the opposite, in fact.

The game begins with the iconic opening-credits sequence from the show, which serves as a fine demonstration of the exceptional video fidelity. The cast credits are not updated; David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson are still listed as the only stars. “What are we?” demand Jordan Lee Williams and Paige Witte. “Chopped liver?” Well, kind of, yeah…

Agent Craig Willmore, who, we learn from perusing his office and his apartment, is a recently divorced father of one with a fondness for the American Civil War and the Ramones. His name is lifted from the third-season episode “Syzygy,” where it’s mentioned unfavorably by two telekinetic teenage girls who are terrorizing a small town: “Hate him, hate him, wouldn’t want to date him.” (Sheesh… as if it wasn’t hard enough already to step into Fox Mulder’s shoes.) The script is littered with little in-jokes and callbacks like this.

In another example of the game’s fan service, you find a copy of Jose Chung’s book from the much-admired third-season episode of the same name. The dilemma to be pondered, I suppose, is where you draw the line between fan service and identity crisis.

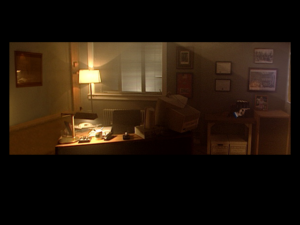

Navigation is of the node-based first-person stripe that was popularized by Myst, but the scenes are all built from photographs of real sets rather than being the output of a 3D modeller. Just look at how this scene and the one below are lit. The game absolutely nails the X-Files visual aesthetic.

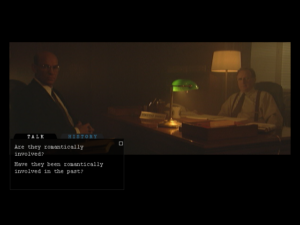

Ken Starr had nothing on this guy. Informed by Assistant Director Skinner of Mulder and Scully’s disappearance, the question that Agent Willmore most emphatically wants an answer to is whether they are now knocking boots or have ever done so. To be fair, the same question obsessed a substantial chunk of the X-Files fan base.

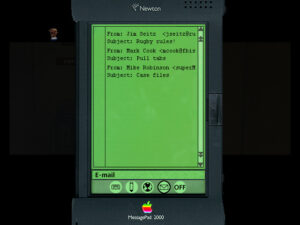

In a clear sign of this game’s long gestation time, Agent Willmore keeps tabs on events in the field with an Apple Newton. Apple discontinued its innovative but flawed “personal digital assistant” a few months before The X-Files Game was released.

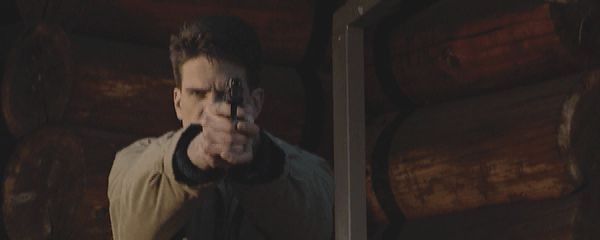

Hunting a pixel in the dark back room of a warehouse means that we have to squint at the world through the narrow beam of a flashlight. This sort of thing is the source of the game’s only real challenge. Unfortunately, this sort of thing is really no fun at all.

Agent Willmore in full jerk mode. Meeting an Asian man near a potential crime scene, he immediately leaps to questioning his immigration status. And then… what accent? Although The X-Files Game acquits itself well on some fronts, it’s full of little inconsistencies like these that mark it as not quite ready for prime time. (“James Wong,” by the way, is the name of a regular X-Files scriptwriter, responsible for the early standout episode “Ice” among many others.)

Canned video clips may have seemed inherently more “dramatic” than conventional computer graphics to people like Greg Roach, but they’re a horribly blunt instrument to try to build a game around, leaving no room for emergent behavior whatsoever. The last disc of of The X-Files Game is a fine example of this. It ought to be a series of heart-pounding action sequences, but, because the only things the game can show you are things that have been filmed, it turns instead into a tedious exercise in figuring out what sequence of events were written down beforehand in the script. Doing anything else leads to a summary judgment of instant death for the crime of failing to read the scriptwriter’s mind.

As if the anachronistic quality of its interactive-movie conceit hadn’t been problem enough, the commercial prospects of The X-Files Game were badly damaged by yet another factor. It had been Fox Interactive and HyperBole’s intention all along to release the game in June of 1998 not only for Windows and the Mac, but also in a version for the Sony PlayStation. Doing so would have broadened its potential customer base almost exponentially. But, lacking expertise on the more constrained, finicky console, HyperBole made the fateful decision to outsource the port to a third party, who rewarded their faith by dropping the ball entirely. There was no alternative but to release on computers only and then try to do the PlayStation port in-house. Thanks to heroic efforts on the part of their programmers, HyperBole did get it done, delivering a port that doesn’t look or play all that much worse than the computer versions — a remarkable feat indeed, considering the disparities of hardware involved. Yet it took them until well into 1999 to get it ready, by which time the game only seemed like that much more of an anachronism.

Despite it all, Greg Roach claims that The X-Files Game sold “in the region of” 1 million copies when all was said and done. I suppose that such a figure isn’t completely out of the bounds of possibility when the console version and bargain bins are taken into account; the PlayStation had such mass popularity and market penetration at this time that a turd in a box with the Sony logo on it would probably have shifted a few hundred thousand units. Whatever the real numbers, though, there was never any serious talk during the remainder of the television show’s run of funding another X-Files game, of the interactive-movie or any other style, made by HyperBole or anyone else. This alone is ample evidence that the first game wasn’t a rip-roaring success.

The cultural moment that could spawn studios like HyperBole was well and truly past by 1998; the company never won another contract of anywhere close to this one’s prominence and size, in fact never made another boxed computer game of any sort. A downsized HyperBole subsisted on small Web-development contracts and the like for a while, before closing up shop for good in 2005.

By that time, Greg Roach was well on the way to his next big thing. He says that he experienced a “tremendously powerful spiritual awakening” in 1998, when he celebrated shipping The X-Files Game with a trip to Egypt to see the Pyramids of Giza. There he was contacted by a group of trans-dimensional beings of pure energy whom he has come to call the Council of Light. (He adopted this appellation after his first name for them, the White Brotherhood, proved to have all the wrong connotations.) The shuttering of HyperBole coincided with his founding of Spirit Quest Tours, offering “life-changing spiritual travel” to those who, like Fox Mulder, really, really Want to Believe. As of this writing, you can find enlightenment for twelve days in Peru for just $7950, not including airfare, meals, single supplement, or “personal expenses.” Nobody ever said that The Truth Out There would come cheap.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books The X-Files Game: Prima’s Official Strategy Guide by Rick Barba and Writing for Interactive Media: The Complete Guide by Jon Samsel and Darryl Wimberley. Computer Gaming World of June 1994, July 1994, February 1995, August 1998, and September 1998; Edge of January 2011; MacUser of December 1992; CD-ROM Today of August/September 1994; InCider of September 1991; PC Games of September 1998; Extreme PlayStation of August 1999 and September 1999. My thanks to reader Busca for digging up a few of these magazine sources for me!

Online sources include GameSpot’s vintage review of the game, the old HyperBole site, Greg Roach’s personal site, his Spirit Quest Tours site, “Greg Roach Wants You to Make a Spiritual Pilgrimage” by Christine Desadeleer at Matador Network, Roach being interviewed by Dr. Sarah Larsen, and an old “making of” reel for the game.

Where to Get It: The X-Files Game has never been re-released for digital purchase, doubtless due to the complications of licensing deals. The easiest way to play it today is to download the pre-packaged version at The Collection Chamber.