Of all the creators I’ve written about so far on this blog, the Austin brothers of Level 9 have frustrated me the most, purely on account of their immense unrealized potential. They could have been great, I tell you. They could have been contenders. But timing and circumstances kept it all from ever quite coming together for them.

At first glance, that may seem an odd statement. Certainly one could hardly say that Level 9’s life was cut unduly short. On the contrary, the Austin brothers got a good long kick at the can as such things go, releasing their first text adventures in 1982 and their last fully seven years later. While hardly a huge stretch of time in the grand scheme of things, that stretch does correspond exactly with the beginning and end of the period in which it was practically possible to earn a living selling text adventures in Britain. Level 9, in other words, had all the time at their disposal that, barring sweeping games-industry counterfactuals, they could possibly have been allowed. During those years, they released more text adventures than any developer this side of Infocom.

Compare this with the sharply abbreviated career of Magnetic Scrolls, their rival for the title of “the British Infocom.” Arriving on the scene in earnest only in 1986, Magnetic Scrolls had just barely enough time to cause a brief splash before getting to enjoying their chosen genre’s steady, painful decline into commercial obsolescence.

Look a little harder, however, and we can see that Magnetic Scrolls also enjoyed some advantages that rather offset the sheer brevity of their window of opportunity. Never more than a very small company though they were, in comparison to Level 9 Magnetic Scrolls was very well-capitalized, thanks to the considerable amount of familial wealth that co-founder Anita Sinclair had on-hand to put into her company. It’s doubtful whether Magnetic Scrolls even during their best years of 1986 and 1987 made more than a very modest profit, and that must have been more than wiped away by the unusually long technological run-up to those years of prominence — and of course by the painful years of decline that followed them. Like that of Infocom, the final balance sheet for Magnetic Scrolls must show a company that lost far, far more money than it earned, an abject failure by the harsh capitalistic logic of pounds and pence.

But Level 9 didn’t have the luxury of being able to lose money for years on end. Founded on a shoestring by a family of modest means, they needed to consistently earn at least as much money as they spent in order to keep the doors open. And with text adventures a relative niche market in Britain even at their commercial peak, the only way to do so was to pump out a lot of games quickly.

And so we come to the crux of Level 9’s problems, and the root of my own frustration with them. Forced to make three, four, even five games each year, the little trio of brothers couldn’t possibly test and polish each of them as they ought. The same relentless financial pressure forced them — so they believed, at any rate — to make their games available on the widest possible range of platforms, including the tape-based machines that Magnetic Scrolls (and Infocom) eschewed. Level 9’s compression techniques were truly masterful, the envy of any of their rivals, but even with them to hand there was only so much complexity and polish they could pack into 48 K of memory.

It should be noted that the judgments I make on Level 9’s games today are indeed contemporary judgments. In their day, most of them were very well-received. Used to short, primitive games created with the likes of The Quill, reviewers readily forgave dodgy puzzles, occasional parsing problems, and bugs and glitches galore to be able to wander in such comparatively huge and complicated worlds as those provided by Level 9. Some of their games contained as many as 200 locations, and their parser, while falling far short of Infocom’s standards, was certainly the best available from a British company prior to the arrival of Magnetic Scrolls. Yet, anachronistic as the judgement may be, Level 9’s games just haven’t aged very well in comparison to the games of Infocom and even Magnetic Scrolls, and we do need to acknowledge the failings that had to be there from the beginning to bring that about.

The situation is doubly infuriating in light of how good — how innovative — Level 9’s abstract design instincts were. In 1983’s Snowball, they endeavored to tell a consistent story in a coherent world, constructing a grand space opera with a premise worthy of Asimov or Niven at a time when virtually no one else in Britain was thinking of text adventures in those terms, before even Infocom had started referring to their works as “interactive fiction.” In 1985’s Red Moon, they combined a system of magic with combat and CRPG-like emergent mechanics, more than two years before Infocom’s text-adventure/CRPG hybrid Beyond Zork. In 1987’s Knight Orc, they pushed further into the realms of simulation and emergence, debuting their KAOS system of autonomous non-player characters, active inhabitants of an active world who can be not just fought but also befriended and ordered about by you, letting you become the director of your own little play.

Next to such innovations, the text adventures of Magnetic Scrolls, all very derivative of Infocom’s first handful of games, seem rather safe and, well, unadventurous. Some of Level 9’s ideas would still be regarded as innovative in a modern game. How heartbreaking, then, that all of the Level 9 games I’ve just mentioned, and so many more besides, are largely undone by some combination of bugs and playability issues. The situation is so frustrating that I often feel an urge to fix it, to go back through the Level 9 catalog and re-implement each game as it ought to have been the first time around, to bring all the good ideas to the fore where they can be appreciated at last. But that won’t be happening any time soon; maybe in my retirement years, when I’ve grown rich from blogging (a man can dream, can’t he?).

In the meantime, we must take Level 9 as we find them. How welcome, then, that not quite every game in their substantial catalog falls down before reaching the finish line. I’ve finally found my personal Holy Grail of a Level 9 game that doesn’t wind up infuriating me before it’s over. And I found it in a very unlikely candidate, in a game that’s far from being one of their more celebrated.

Gnome Ranger was created during 1987, a difficult period for Level 9. The contract they had signed with Rainbird the previous year, seen at the time as their big shot to take things to the next level (Level 10?), had instead left them playing second fiddle to Magnetic Scrolls; all of their own efforts for Rainbird wound up being overshadowed by those of their stablemate. Rainbird wasn’t thrilled with Jewels of Darkness or Silicon Dreams, Level 9’s reworkings of past glories. They were still less thrilled with Knight Orc, which the perpetually overworked Austin brothers delivered very late and riddled with bugs. With sales of all the Level 9 games lagging far behind those of Magnetic Scrolls, Rainbird saw little reason to retain a second British text-adventure house on the label. This parting was deeply disappointing for the Austin brothers, not least in that it dashed their fondest dream, that of breaking through in the United States; the three Rainbird releases had been the first Level 9 games ever to be made available to Americans.

But there was nothing for it but to soldier on alone. Gnome Ranger, the next game in the pipeline, would have been a Rainbird release if all had gone well. Instead they would just release it themselves, like they had done in the old days. They did, however, take some lessons from the split with Rainbird, making an effort to improve their quality control by instituting a real play-testing cycle of one month’s duration. One month wasn’t, needless to say, anywhere near enough to bring a Level 9 game up to the level of polish enjoyed by Infocom’s players, but it was a much-needed step in the right direction. The benefits are immediately apparent in the finished game, rough around the edges though it does indeed still feel in comparison to Infocom.

Like Knight Orc, Gnome Ranger is on the surface at least a comedy, a genre Level 9 had rarely explored in their many earlier games. And also like Knight Orc, Gnome Ranger is named after the character you play, this time a little busybody of a gnome named Ingrid Bottomlow who’s irritated her entire village so badly that they’ve contrived to teleport her far, far away just to get her out of their hair. As Ingrid the clueless perpetual innocent, who assumes the whole incident was just an unfortunate mishap, you have to make your way back home on foot. Adventure, naturally, ensues.

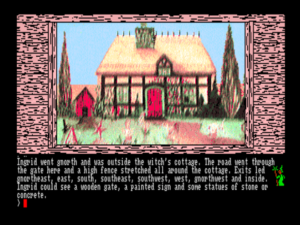

Like Knight Orc, Gnome Ranger uses scanned colored-pencil drawings for illustrations. They were very polarizing at the time. I like their Impressionistic quality myself, and certainly think they suit this game much better than they did Knight Orc.

Gnome Ranger resembles Knight Orc in many other particulars, among them a fun novella to set the stage, written by regular Level 9 collaborator Peter McBride, and the KAOS system of active non-player characters and the many puzzles revolving around giving orders to and coordinating the actions of same. Yet its tone is much, much gentler. Replacing the savage humor of Knight Orc is a more whimsical spirit one might even describe as “cute” — certainly an adjective you’re very unlikely to apply to anything about the earlier game. For instance, in a move you’ll either find hilarious or unbearably twee, every single word that starts with “n” in standard English starts with “gn” in Gnome Ranger: “Gnow what?” it asks when it’s ready for your first command. I find it unaccountably funny myself, and somehow even funnier that Level 9 is so dedicated to the joke that they seldom miss a word. (No, you don’t have to enter your commands using the alternative spellings, although you can if you really want to get into the spirit of the thing.)

Once again like Knight Orc and the other late Level 9 games, Gnome Ranger is divided into three separate acts, each a small, self-contained game in its own right. This division permitted the whole to run on the modest likes of a tape-based Sinclair Spectrum, and, more to our contemporary benefit, kept the design of each section compact and manageable. The three stages of Ingrid’s journey home each have a theme: animal, vegetable, and mineral. My favorite is the second, a series of brilliant little puzzles involving the assembling and use of a series of magic potions, culminating in a recipe for the ultimate cup of tea. Yes, this is a very English game, feeling much more naturally so than the sometimes strained attempts by Magnetic Scrolls to evoke the spirits of Monty Python and Douglas Adams for the American players they were hoping to reach. In contrast to the London-based Magnetic Scrolls, Level 9’s offices remained always in quiet villages and suburbs, in the real bosom of England’s green and pleasant land. The detailed descriptions of the flora in particular evince the love of gardening that was shared by the Austins and Peter McBride, who wrote much of the in-game text as well as the accompanying novella. Like so many other writers and readers who belatedly realize that small stories are usually more compelling than epic ones, the Austins are perhaps growing up here, deliberately eschewing the nerdy bombast of something like Snowball. Like the English countryside they so dearly loved, the pleasures of Gnome Ranger are modest in scale, but no less entrancing for it when you give the game a chance.

Gnome Ranger and most of the other late Level 9 games are among the few text adventures written in the third-person past tense. The tense was presumably chosen to enhance the narrative qualities. In my judgment, it really doesn’t, but it doesn’t distract unduly either.

The KAOS system is still present in Gnome Ranger, the ordering about of a whole squad of helpers still the solution to many puzzles, but it’s toned down considerably here in comparison to the exercise in unhinged chaos (KAOS?) that is Knight Orc. Having developed a new set of tools, Level 9 is now learning how to use them. With most of the weirdness excised, what remains is a compelling set of puzzle mechanics that allows lots of alternate solutions to the problems you encounter, that gives solving the puzzles less of a feeling of stumbling onto the one arbitrary correct command and more of a feeling of taking advantage of emergent circumstance, of strategizing your way to success. Soluble but not trivial, gently funny without trying too hard to be, Gnome Ranger is wonderful to experience as crossword and narrative alike. It’s by far my favorite of Level 9’s games.

It seems that little Ingrid Bottomlow was also a favorite of the Austin brothers, for they chose to revisit her in a sequel, titled Ingrid’s Back!, in 1988. She’s arrived back home again only to find her village in danger of being steamrolled by one Jasper Quickbuck, a greedy real-estate developer whose presence provides a dash of political commentary about the ongoing gentrification of so many British towns and villages. Suddenly there’s need in her village for a busybody like Ingrid; it’s up to her — that is to say, to you — to save it.

The other inhabitants of the village are described with delightful wit.

He was a dwarf from the gnorth, who measured for pleasure with his pole in a hole and his theodolite on the right.

He was the local fishergnome, gnow doubling as the ferrygnome since the Dribble Bridge collapsed. He gnever did much ferrying because he was always busy fishing to supply the Green Gnome, which was crowded with stranded travellers who were waiting for the ferry.

He was a travelling leprechaun, who spent his days peddling his charms to housewives everywhere. He was very small, but very jolly, and given to saying that size wasn’t everything.

He was the family rabbit-herd. He couldn’t decide if he was keeping rabbits for their meat, milk, or fur, but it didn’t matter anyway because the rabbits wouldn’t let him have any of them.

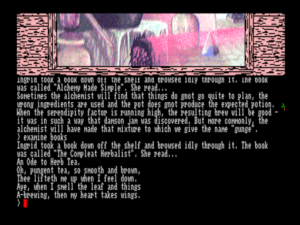

For Ingrid’s Back!, Level 9 switched to more traditional computer-drawn pictures, although theirs were never quite as good as those of Magnetic Scrolls.

Once again, the second act is my favorite here. It deals with an assault on the village by a demolition crew of trolls. You have to dash about dealing with them one after another through tricks and booby traps. The presence of a harsh time limit makes the experience more stressful than anything in Gnome Ranger, but it’s great fun to dispatch the trolls one by one through ever more hilarious means.

I should take a moment to note that by “dispatch” I don’t mean kill; no one ever has to die in either of the Gnome Ranger games, something else I like about them. The Austin brothers regarded violent games with a certain contempt, calling them “vomit games” after the squelching sounds of blood and guts. Pete Austin:

Most advertising seems to emphasize the violent aspect of games, and, while nobody wants things like My Little Pony prancing about, it would be better to point out that computer programs can be interesting, informative, and broaden the mind. Unfortunately, violence does succeed in selling. If you have an essentially boring concept, the best way to jazz it up is to add some blood. This is what Hollywood has been doing successfully for years, but what you really need is a good script.

But sadly, Ingrid’s Back! itself lacks a good script — or, at any rate, a good puzzle structure — in its first and third acts. There’s precious little to really do at all during the last act in particular; with only a few exceptions, you just have to wander around and collect things. It’s as if in their newfound zeal for solubility the Austins have decided to remove the puzzles entirely. It makes a sad contrast to the compelling puzzles of Gnome Ranger, one almost certainly attributable to the time pressures that were now becoming even more acute as text adventures faded in popularity and each successive game Level 9 released sold fewer copies.

Many of the same old issues of bugs and playability began to creep back into Ingrid’s Back! and Level 9’s other late games. The experience of properly testing Gnome Ranger, while certainly resulting in a better game, provided a mixed lesson on the whole. Many of the outside testers, the Austins believed, decided to share the game with their friends; Pete Austin claimed that some of the problems he saw people writing to the magazines about existed only in the beta versions. Subsequent games were thus not tested as extensively — or possibly, given the state of some of them, not tested at all. “We have to walk this tightrope,” Pete said, “and make these compromises in getting it tested enough to get the bugs out but not enough to get too much piracy.” Such a “compromise” could have only a negative effect on the end result.

Also not doing much to cement Level 9’s commitment to quality control was the fact that they received little obvious reward for it either critically or commercially. Many reviewers, apparently poorly equipped by disposition to appreciate Gnome Ranger‘s pastoral pleasures, were nonplussed by Level 9’s eschewing of the epic for the intimate. There was considerable grumbling, considerable nostalgia for the good old days of sprawling maps with 200 locations — for, ironically, the very attributes Level 9 themselves had used as their primary selling points in the early days. It was all part of a general turning away from Level 9 on the part of the British gaming press, who had always feted them as the undisputed kings of adventure gaming in earlier years but were now hopelessly enamored with Magnetic Scrolls. For the Austins, who in contrast to Anita Sinclair and her band of upstarts had been on the scene since the beginning, it must have felt like a betrayal by old friends.

The Austins were reported to have a third Gnome Ranger game, the conclusion of what had always been planned as a trilogy, designed and ready for implementation by early 1989, but wound up retiring from the text-adventure scene before getting a chance to do so. Ah, well, at least we have the first two — and especially the first. Unloved and largely unremarked even in its own day though it was, its discovery marks the fulfillment of a personal quest I’ve been on for a long time now: the quest for at least one Level 9 game I can unreservedly enjoy and tell you to play. I can, and you should.

To make that as easy as possible for you, I’ve prepared a zip file containing Gnome Ranger and its sequel in two formats. The first, which is strictly for the hardcore or the purist, is the disk images of the original Amiga versions, playable in an Amiga emulator. The other, more accessible format will work under Glen Summer’s Level 9 interpreter, which is available for many platforms. Once you’ve downloaded the correct version of the interpreter for your computer, just fire it up and open the file “gamedata1.dat” from either game’s directory to play.

Soon it will be time to put a bow on the tale of the 1980s British text adventure in general and Level 9 in particular, but before we do so I want to take you on one final detour back to earlier years. My next story is not about a computer game at all, but it is a story some of you have asked for specifically, and one we’ve already met tangentially several times. And it’s most definitely a story that’s worthy of more than mentions in passing. So, next time we’ll finally do proper justice to Kit Williams and his golden hare.

(Sources: Retro Gamer 7; Crash of February 1988; Page 6 of July/August 1988 and June/July 1989; ACE of December 1987; Amstrad Action of September 1988 and October 1988; Games Machine of December 1988; Zzap! of January 1989.)