The American home-computer industry entered 1987 feeling more optimistic than it had in several years. With the bloodletting of 1985 now firmly in the past, there was a sense amongst the survivors that they had proved themselves the fittest and smartest. If the ebullient a-computer-for-every-home predictions of 1983 weren’t likely to be repeated anytime soon, it was also true that the question on everybody’s lips back in 1985, of whether there would even still be a home-computer industry come 1987, felt equally passé. No, the home-computer industry wasn’t going anywhere. It was just too much an established thing now. Perhaps it wasn’t quite as mainstream as television, but it had built a base of loyal customers and a whole infrastructure to serve them. And with so many companies having dropped by the wayside, there was now again the potential to make a pretty good living there. The economic correction to a new middle way was just about complete. The industry, in other words, was beginning to grow up — and thank God for it. Even Atari and Commodore, the two most critical hardware players in the field of low-cost computing, had seemingly gotten their act together after being all but left for dead a couple of years ago; both were beginning to post modest profits again.

The mood of the industry was, as usual, reflected by the trade shows. The second of the two big shows that served as the linchpin of every year on the circuit, the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago in June, was a particularly exciting place to be, with more and more elaborate displays than had been seen there in a long, long time. Compute! magazine couldn’t help but compare it to “the go-go days of 1983,” but also was quick to note that “introductions are positioned to avoid any repeat of the downturn.” “Excited but wiser” could have served as the slogan of the show. But an even better slogan for entertainment-software publishers in particular might have been, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

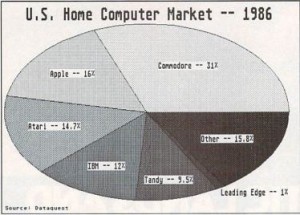

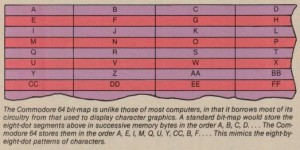

I’ve been writing quite a lot in recent articles about the new generation of 68000-based machines that were causing so much excitement. Yet the fact is that the Apple Macintosh, Atari ST, and Commodore Amiga were little more than aspirational dreams for the majority of the mostly young people actually buying games. The heart of that market remained the cheaper, tried-and-true 8-bit machines which continued to outsell their flashier younger brothers by factors of five or ten to one. And the most popular 8-bit machine had remained the same since 1983: the Commodore 64. A chart published in the December 1986 Compute! gives a sense of the state of the industry at the time.

If anything, this chart undersells the importance of the Commodore 64 and its parent company to the games industry. Plenty of those IBMs and Apples, as well as the “Other” category, made up mostly of PC clones, were being used in home offices and the like, playing games if at all only as an occasional sideline. The vast majority of Commodore 64s, however, were being used primarily or exclusively as games machines. Many a publisher that dutifully ported their titles to each of the six or seven commercially viable platforms found that well over half of their sales were racked up by the Commodore 64 versions alone. No wonder so many made it their first and sometimes only target. Not all were thrilled about this state of affairs; with its antiquated BASIC, chunky 40-column text, and molasses-slow disk drives the Commodore 64 was far from a favorite of many programmers, so much so that a surprising number developed elaborate cross-compiler setups to let them write their 64 programs anywhere else but on an actual 64. Many others who had had personal dealings with Commodore, particularly in the double-crossing bad old days of Jack Tramiel, simply hated the company and by extension its products on principle. Yet you couldn’t hate them too much: fact was that the 64 was the main reason there still was any games industry to speak of in 1987.

Already the best-selling microcomputer in history well before 1987, the Commodore 64 just kept on selling, with sales hitting 7 million that year. Meanwhile sales of the newer Commodore 128 that could also play 64 games cruised past 1 million. This continued success was a tribute to the huge catalog of available games. As Bing Gordon of Electronic Arts put it, “The Commodore 64 is the IBM of home computing; no one thinks you’re dumb if you buy it.” Of course, this aberrational era when a full-fledged computer rather than a games console was the most popular way to play games in the country couldn’t last forever. Anyone sufficiently prescient could already see the writing on the wall by wandering to other areas of that Summer CES show floor, where an upstart console from Japan called the Nintendo Entertainment System was coming on strong, defying the conventional wisdom of just a year or two before that consoles were dead and buried. But for now, for just a little while longer, the Commodore 64 was still king, and Summer CES reflected also that reality with a final great flowering of games. Love it or hate it, programmers knew the 64 more intimately by 1987 than they possibly can the complex systems of today. They knew its every nook and cranny, its every quirk and glitch, and exploited all of them in the course of pushing the little breadbox to places that would have been literally unimaginable when it had made its debut five years before; plenty of games and other software stole ideas from the bigger, newer machines that simply didn’t yet exist to steal in 1982.

Starting today, I want to devote a few articles to chronicling the Commodore 64 at its peak, as represented by the games and companies on display at that 1987 Summer CES. We’ll start with Epyx, whose display was amongst the most elaborate on the show floor, an ersatz beach complete with sand, surfboards, Frisbees, and even a living palm tree. It was all in service of something called California Games, the fifth and newest entry in a series that would go down in history as the most sustainedly popular in the long life of the Commodore 64. If we were to try to name a peak moment for Epyx and their Games series, it would have to be the same as that for the platform with which they were so closely identified: Summer CES, June 1987.

You can get a pretty good sense of the advancement of Commodore 64 graphics and sound during its years as the king of North American gaming just by looking at the Games series. In fact, that’s exactly what we’re going to do today. We’re going to take a little tour of four of the five Games, hitting on just a couple of events from each that will hopefully give us a good overview of just how much Commodore 64 graphics and sound, along with gamer expectations of same, evolved during the years of the platform’s ascendency. These titles were so popular, so identified with the Commodore 64, that they strike me as the perfect choice for the purpose. And they also occupy a soft spot in my heart as games designed to be played with others; they’re really not that much fun played alone, but they can still be ridiculously entertaining today if you can gather one to seven friends in your living room. Any game that encourages you to get together in the real world with real people already has a huge leg up in my critical judgment. I just wish there were more of them.

Let’s start by taking another look at the original 1984 Summer Games, a game I already covered in considerable technical detail in an earlier article. Its graphics — particularly the fluid and realistic movements of the athletes themselves — were quite impressive in their day, but look decidedly minimalist in light of what would come later. Also notable is the complete lack of humor or whimsy or, one might even say, personality. Those qualities, allowed as they to a large extent are by better and richer audiovisuals, would arrive only in later iterations.

Few concepts in the history of gaming have lent themselves as well to almost endless iteration as the basic Games concept of a themed collection of sporting minigames. Thus after Summer Games turned into a huge hit more Games were inevitable, even if they wouldn’t be able to piggyback on an Olympics as Summer Games had so adroitly managed despite the lack of an official license. The first thought of Epyx’s programmers was, naturally enough, to follow Summer Games with a similar knock-off version of the Winter Olympics. By this time, however, it was late 1984, and Epyx’s marketing honcho Robert Botch said, probably correctly — he tended to be correct in most things — that a winter-sports game would be a hard sell when they finished it up in six or eight months; at that time, you see, it would be high summer. So they instead turned their attention to Summer Games II, consisting of eight more events, many of which had been proposed for the original collection but rejected for one reason or another. It proved to be if anything a better collection than its predecessor, with more variety and without the cheat of inserting two swimming events that were exactly the same but for their differing lengths. Graphics and sound were also modestly improved.

But the first really dramatic leap forward in those areas came with the next iteration, the long-awaited Winter Olympics-themed Winter Games that followed hot on the heels of Summer Games II. With Epyx’s in-house programmers and artists still busy with the latter, Winter Games was outsourced along with detailed specifications provided by Epyx’s own designers to another developer called Action Graphics. The partnership between the Silicon Valley-based Epyx and the Chicago-based Action Graphics was apparently a somewhat troubled one, with delays caused by poor communication threatening to scupper the planned Christmas 1985 launch. The project’s savior proved to be one Matt Householder, a recently arrived refugee from Atari who would play a huge role in the series going forward. Upon his hiring in July of 1985, his first role became that of Epyx’s official liaison to Action Graphics; he spent many weeks in Chicago pushing the game along to completion. A programmer himself with much experience with videogames, Householder suggested lots of extra little touches, sometimes helped out with technical problems, and, with the deadline ever looming, occasionally advanced the timetable via some artful deletion.

The bobsled was a particularly problem-plagued event. The original conception would have had the riders pushing the sled to get it started, just like in the real thing, but no one could quite figure out how to make it work. Householder made an executive decision to just excise that element entirely in favor of making the rest of the event as good as possible. Note in the video below how the clouds in the sky also move when the bobsled goes through a curve. This late Householder-prompted addition is a classic example of a little touch of the realistic whose presence might not be noticed but whose absence almost certainly would — perhaps not consciously, but only as a feeling that something is somehow “off” with the experience. Note also the music that now plays before this and all of the other Winter Games events to leaven the somewhat sterile feel of the original Summer Games.

The bobsled is actually quite graphically spare in contrast to some of the other events in Winter Games. See for example the biathlon, the most time-consuming single event to appear in any of the Games games and one of the most strategic. The speed of the targeting cursor in the shooting sections — and thus the difficulty of each shot — is determined by your heart rate when you arrive. Success is all about pacing yourself, setting up a manageable rhythm that keeps you moving along reasonably well but that also lets you make your shots. According to Householder, “It was put in there to make something completely different. It breaks up the pace of the other events, which are more tense, action/reaction type of things. You have to learn a different set of skills.” Barely a week before the deadline, Householder, bothered that the shooting just somehow didn’t feel right, suddenly suggested adding a requirement to eject the spent round and cock a new one before firing. They managed to shoehorn it in, and it does go a long way in adding verisimilitude to the experience. It’s not so important to make a game like this realistic per se, but to make the player feel like she’s really there, to capture the spirit of the event, if you will.

The original plan for the graphic depictions of this event was, as with the bobsled, somewhat more ambitious than the final version. The skier was to be shown from different angles on every screen, a scheme that Householder quickly excised in favor of a consistent if less graphically interesting side view. The lush backgrounds were inspired by photos of the actual event taken at the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo, recreated freehand by artist Steve Johnson. I must say that I love the winter-wonderland atmosphere that this event and, indeed, much of Winter Games conjures up. Like the opening and closing ceremonies, the bobsled, and a couple of other events in Winter Games that clearly take inspiration from the Sarajevo Olympics, the biathlon is made bittersweet today by the knowledge of what was in store for so many of those sites and, more importantly, for the people who lived near them.

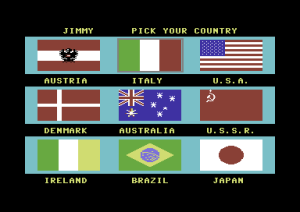

Having now covered most of the Olympics events that seemed practical to implement on a Commodore 64, there was some debate within Epyx on the best way to consider the series after Winter Games; it had turned into such a cash cow that no one was eager to bring it to a close. Marketing director Robert Botch suggested that Epyx effectively create their own version of the Olympics using interesting non-Olympic sports from all over the world, under the title of World Games. Householder ran with the idea, proposing turning the game into a sort of globe-trotting travelogue that would not only let the player participate in the unique sports of many nations but also get a taste of their cultures.

You’ll notice in the World Games screenshot above an advertisement for Continental Airlines, perhaps the first of its kind in a game that wasn’t itself blatant ad-ware and yet another example of Botch’s prescience as a marketer. If the times were changing, though, they were still changing slowly: Continental was able to buy this exposure in a game that would end up selling hundreds of thousands of copies by providing Epyx with nothing more than a handful of free tickets to Disney World for use in contests. On the other hand, perhaps Continental paid a fair price when one starts to consider demographic realities; the young people who made up the vast majority of Epyx’s customers generally weren’t much in the market for airline tickets quite yet.

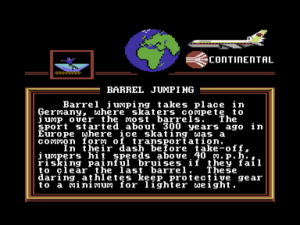

Much as the documentary tone of the travelogue-style descriptions might lead you to believe otherwise, the Epyx design team was made up of a bunch of young American males who weren’t exactly well-traveled themselves, nor much versed in global sporting culture. They chose the majority of the sports in World Games by flipping through books and magazines, looking for things that seemed interesting and implementable. They then designed the events without ever having actually seen them in real life. This led to some bizarre decisions and outright mistakes, like their choice of barrel-jumping (on ice skates!) as the supposed national sport of Germany; absolutely no one in Germany had any idea what they were on about when the game came out. Their original plan to make soccer penalty kicks Germany’s national sport would have hit closer to home, even if a love for soccer is hardly confined to that country. But it proved to be technically infeasible.

With Epyx’s in-house programming team once again too busy with other projects to take it up, World Games was again contracted to outside programmers. This time a company called K-Byte did the honors, albeit under much closer supervision, with the art and music supplied by Epyx’s own people. Freed as they were from the rigid strictures of traditional Olympic disciplines and a certain fuddy-duddy air of solemnity that always accompanies them, the designers, artists, and programmers were able to inject much more creative whimsy, even humor. See for example what happens when you screw up badly in Scotland’s caber toss.

Speaking of screwing up: Epyx’s designers managed to completely miss the point of the caber toss. Athletes participating in the real sport are judged on aesthetics, on how cleanly and straightly they toss the caber. The objective is not, as in World Games, to simply chunk the bloody thing as far as possible.

The music tries its best — if, again, only within the limits of Epyx’s international awareness — to echo the “national music” of each country represented. The bagpipe sound is quite impressive in its way; listen for the initial “squawk” each time the instrument changes pitch, so like the real thing.

But Mexico’s cliff-diving provides perhaps the best illustration of how far Epyx had come already by the time of World Games. It’s superficially similar to the diving event from Summer Games, as seen in my very first video above, but the difference is night and day. I speak not just of the heightened drama inherent in jumping off a rocky cliffside as opposed to a diving board, although that’s certainly part of it. Look also at the improved graphics, the addition of music, all of the little juicy touches that add personality and interest: the way the diver fidgets nervously as he waits to take the plunge, the way you can send him careening off the rocks in various viscerally painful ways, the seagull at the bottom of the cliff who will turn and fly off if you wait long enough. (Rumor has it that it’s possible to hit the seagull somehow if you botch a dive badly enough, but I’ve never succeeded in doing so.)

California Games, the fifth entry in the series and the culmination of the audiovisual progression we’ve been charting, was done completely in-house at Epyx. Indeed, it was also inspired much closer to home than any of the games that had come before. Walking through Golden Gate Park one weekend, watching bicyclists and skateboarders doing tricks for the crowds, Matt Householder’s wife Candi suggested that Epyx should use those sorts of sports in their next Games game.

But there’s a bit more than that to be said about California Games‘s origins, in terms of both universals and the specific context of the mid-1980s. In the case of the former, there’s the eternal promised land of California itself that’s been a part of the collective mythical landscape of Americans and non-Americans alike almost from the moment that California itself existed as a term of geography: Hollywood, Route 66, Disneyland, the Sunset Strip, the Beach Boys, palm trees, hot rods, surfboards, and of course bikinis and the sun-kissed beach bunnies who fill them out so fetchingly. (Botch wouldn’t be shy about incorporating the latter elements in particular into his marketing campaign.) “Go west, young man!” indeed. California Games combined this eternal California with a burgeoning interest amongst the young in what would come to be called “extreme sports” that saw many a teenager picking up BMX or half-pipe skateboarding. The first proposal that Householder submitted actually skewed much more extreme than the eventual finished product, including wind-surfing, hang-gliding, and parachuting events that were all excised in favor of some more sedate pursuits like Frisbee and Hacky Sack. He also proposed for the collection the almost instantly dating appellation of Rad Games; thankfully, Botch soon settled on the timeless California Games instead.

Which is not to say that California Games itself is exactly “timeless”; this is about as clearly a product of 1987 as it’s possible for a game to be. At that time the endlessly renewable California Dream was particularly hot. Even the name California Games, timeless or no, also managed to evoke the zeitgeist of 1987, when California Coolers and the California Raisins were all the rage. The manual includes a helpful dictionary of now painfully dated surfer and valley-girl slang.

LIKE (lik) prep. Insert anywhere you like, like, in any sentence, in, like, any context. Used most effectively when upset: “it’s, like, geez…” Or the coolest way to use “like” is with “all” (for more description). “It’s, like — I’m all — duuude, you’ve got sand in your jams.”

Replacing the chance to represent a country, Olympics-style, that had persisted through World Games are a bunch of prominent 1987 brands, some of which have survived (Costa Del Mar, Kawasaki, Ocean Pacific, Casio), some of which have apparently not (Auzzie Surfboards and Ray-D-O BMX, my favorite for its sheer stupidity). All paid Epyx to feature their logos in the game, with those willing to invest a bit more getting more prominent placement. Yes, Botch was figuring out this in-game-advertising thing fast. See for instance the logos plastered behind the skateboarding half pipe.

California Games was the first title in the series for which Epyx could draw on a fair amount of direct personal experience. Enthusiasts of the various sports inside the company demonstrated their skills for the cameras, the resulting video used as models for their onscreen versions. Some of the less athletic programmers and designers also had a go by way of getting into the spirit of the thing. Householder notes that “I nearly broke my skull a couple of times” on a skateboard in the Epyx parking lot.

To see how far Commodore 64 games came in less than four years, look at the colorful-in-both-senses-of-the-word surfing video below, with its gags like the shark. (A cute dolphin also shows up from time to time, albeit not so often as the shark and never, alas, when you’re trying to make a video.) Notice how the music, a rock song this time, plays during the action now to elevate the whole experience. The bagpipes and the like may have been impressive, but rock and roll was to be the sound of California Games, with Botch even managing to officially license “Louie Louie” for the title screen. And notice how the little surfer dude is an individual with his own look and, one might even say, personality, in comparison to the faceless (literally!) papier-mâché silhouettes of Summer Games.

California Games became an even bigger international hit than the previous four games in the series, one more symbol of the power of the California Dream. Epyx now had 200 employees, and was possessed of an almost unblemished record of commercial success that made them the envy of the industry, their catalog including not only hit games but also their Fast Load cartridge that many Commodore 64 owners considered indispensable and a very popular “competition-quality” joystick. But California Games would mark the end of an era. The downfall of this company and series that had been able to do no wrong for years would happen with stunning speed.

Nor could the Commodore 64 itself keep going forever. Having reached its peak at last in mid-1987, with programmers beginning to get a sense that it just wasn’t possible to push this little machine, extraordinarily flexible as it had proved to be, much further, the downward slope loomed. We, however, will stay perched here a little longer, to appreciate in future articles some more of the most impressive outpouring of games ever to grace the platform.

(Sources: Family Computing of September 1987; Commodore Magazine of July 1988 and August 1989; Commodore User of February 1986; Compute!’s Gazette of December 1986; Compute! of December 1986 and August 1987; Retro Gamer 46 and 49.

Such was the popularity of the first five of the Games that the property still holds some nostalgia value to this day, seeing periodic re-releases and revivals. The latest of these is from the German publisher Magnussoft, who have versions available for Windows, Macintosh, and Android. I must say, however, that there’s little left of the original feel in such efforts. I prefer to just play them in an emulator on the old Commodore 64. An intrepid fan who calls himself “John64” has packaged all five titles onto a cartridge image who loads and plays almost instantly in an emulator like VICE. I take the liberty of providing the cartridge here as well along with all of the manuals.)