As a man of wide-ranging curiosity, Terry Pratchett was drawn to personal computers early. In 1981, he purchased a Sinclair ZX81 in kit form and soldered it together successfully. He soon upgraded to a Sinclair Spectrum and then to an Amstrad CPC 464, which was his first computer strong enough to run a practical word processor. From the second Discworld novel on, he wrote all of his books digitally; this was undoubtedly a factor in the prodigious writing and publishing pace he maintained for so many years. But computers were more than a tool to him: right from the beginning, he also played computer games enthusiastically. In a 1986 interview, for example, he mentions being obsessed with Infocom’s interactive version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

The first Discworld computer game came surprisingly quickly, courtesy of a teenage entrepreneur named Fergus McNeill and his little company Delta 4, who had made a name for themselves by writing slapstick fantasy parodies as Quill-based text adventures, with names like Bored of the Rings (which didn’t share anything but a name and a certain sensibility with the book of the same name) and The Boggit. While it would be a stretch to say that they transcended their author’s age and the technology used to create them, they were amusing in their way, and became quite popular. Some of them reportedly sold as many as 20,000 copies, a very impressive number in the British games industry of the mid-1980s. They made McNeill a natural to adapt Terry Pratchett to an interactive medium, given that the latter’s first couple of Discworld novels were content to plow much the same satirical territory, albeit in a more erudite and sophisticated way.

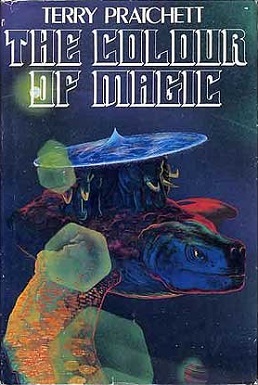

McNeill says that he originally bought the novel The Colour of Magic “as a present for someone else, but I accidentally started reading it myself and found myself unable to stop.” It was he who suggested an adaptation to Pratchett’s publisher, to capitalize on the British appetite for bookware. “It’s important to remember that this was Olden Times — the 1980s, for goodness sake,” he says. “So, when I said ‘Terry Pratchett,’ people didn’t laugh at my audacity for wanting to work with the great man. They frowned and said, “Who’s he?'”

Thus McNeill was able to make the deal, and created his Colour of Magic text adventure in short order, with some direct input from Pratchett himself. The end result, which was released in late 1986 in Britain and Europe only, is an abbreviated version of the novel, walking through its plot scene by scene. Solving it entails looking up what Rincewind did in the same situation in the book, then figuring out how to express the concept to the balky, fiddly parser. Those who have read the book, in other words, will vacillate between boredom and frustration, while those who haven’t will be utterly lost. Even in its day, when a disconcerting number of players were willing to accept fighting the parser as an inherent part of the challenge of playing a text adventure, the game was less popular than its license might suggest.

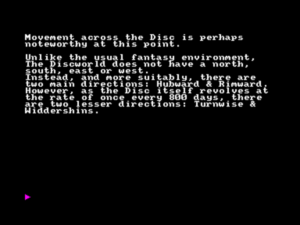

The Colour of Magic replaces the standard text-adventure compass directions with those of the Disc: “hubward,” “rimward,” “turnwise,” and “widdershins.” One plus for verisimilitude, but ten minuses for annoying the heck out of the player.

McNeill speaks of his communications with Pratchett fondly, going so far as to call him “a big inspiration for me,” whilst calling being allowed to make the game at all “a huge privilege.” Yet Pratchett was enough of a gamer himself to recognize how underwhelming the final product really was. In his view, it cheapened the Discworld brand, of which he was always keenly protective; he would refer to the interactive Colour of Magic only as a “bad experience” in later years. It was enough to make him shy away from further game adaptations for quite some time, despite his personal fondness for computers and the games they played. It wasn’t until mid-1993, when Discworld mania was in full swing, that someone managed to convince Pratchett to give the idea of ludic Discworld a second chance.

Actually, there were two someones, the first of whom was one Angela Sutherland, who had gotten her start in the games industry back in 1983. She had been studying to become a sculptor at that time at the Edinburgh College of Art, when a fellow student and good friend named Sandy White had showed her a simple action game called Ant Attack which he had been writing on his Sinclair Spectrum. She helped him to flesh it out and get it published, whereupon it became one of the big early hits on the Speccy. Sutherland worked with White on several more games after that, moved on to become head of development for Firebird and Rainbird, and then became a producer for the British division of Beam Software, the Australian software house famous for The Hobbit, probably the best-selling text adventure of all time (and the thing which Fergus McNeill’s early games were really parodying, at least as much as Tolkien’s books).

Seeing an opportunity in the market, she left Beam and founded her own studio, Teeny Weeny Games, in 1991. Its name reflected its focus: games for handheld systems like the Nintendo Game Boy. Such gadgets were not yet hugely popular among consumers in her home country, but the average British wage was lower than that of the average American or Japanese, making a British studio such as the one she was setting up a good option for big publishers looking to get a product onto the international market quickly and fairly inexpensively, but also competently. So, Teeny Weeny cut their teeth on playable but forgettable licensed fare and ports. For all that it was the games industry’s version of flyover country, this was also a space where a pragmatist like Sutherland could do very well for herself. These sorts of projects would remain the studio’s bread and butter throughout its lifetime.

Teeny Weeny enjoyed an unusual symbiotic relationship with another studio called Perfect 10 Productions, founded at almost the same time by Gregg Barnett, a former colleague of Sutherland from Beam. Perfect 10 had much the same business philosophy as Teeny Weeny, but focused on the full-sized console systems; this created an opportunity for the two developers to collaborate in order to bring the same game out on living-room and handheld consoles. And indeed, they came to share code, assets, strategies, and even office space and to some extent employees with one another, until it became difficult for the outside observer to see where one stopped and the other began.

Thus it was Sutherland and Barnett together who made the pitch to Terry Pratchett for a Discworld adventure game. It seems that their pragmatism had served to conceal a streak of more ambitious creativity, a desire to make something more exciting than the games that were currently keeping the lights on in their offices. But at the same time, they were still hard-nosed enough to appreciate the value of licenses — particularly a license of the biggest literary phenomenon in Britain, a series of novels which Sutherland and Barnett happened to adore, just like millions of their countryfolk.

Pratchett, however, was not easy to convince. It took six months of tireless courting, and ultimately the presentation of a complete design document written by Barnett himself, to get him to say yes. “The main reason he signed,” says Barnett, “was that we did a design, which showed we were willing to put in the work without any initial reward, and that we understood and respected the property.” Sutherland and Barnett promised Pratchett that they would wash away the bad taste of the Colour of Magic text adventure by sparing no expense or effort this time around. They would make a fully-voiced point-and-click graphic adventure for the latest CD-ROM-capable personal computers, one that was as good or better than any of the big titles coming out of the United States.

In fact, the Discworld game almost came out under one of those American publishers’ imprint. Using their international connections to maximum advantage, Sutherland and Barnett signed a deal with Sierra, along with LucasArts one of the two biggest names of all in adventure gaming. The agreement would let them make their game using that company’s state-of-the-art SCI engine, with the support of some Sierra personnel who would temporarily relocate to the project’s South London headquarters. But the American publisher didn’t quite seem to grasp what a huge license Discworld really was on the other side of the Atlantic. Bleeding money from their visionary but unprofitable online gaming space The Sierra Network, they backed out of the deal. Talks with the American giant Electronic Arts also fell through, whereupon Sutherland and Barnett finally signed with the homegrown publisher Psygnosis, best known for the global hit Lemmings, the most popular British-developed videogame prior to the Grand Theft Auto franchise many years later. By virtue of their location at Ground Zero of Discworld mania, Psygnosis knew very well how big a Discworld game could be, such that they had already tried without success to pitch the idea directly to the wary Pratchett. At their first meeting with Sutherland and Barnett, they became the suitor rather than the courted: they “wouldn’t leave until we did a deal,” says Barnett.

Pratchett himself was if anything even more into games now than he had been during the previous decade. For a man who had grown up in a house without electricity or an indoor toilet, the games of the 1990s were nothing short of wondrous. “I play games a lot — and I mean a lot,” he said in a contemporary interview. “Sitting in front of a screen writing, you need some relaxation, and what better way than to load in something like Wing Commander, which is one of my faves. One of the nice things about making lots of money from books is that I can go down to the local Virgin Store and buy what I want!” This habit, combined with his protectiveness of Discworld as a property, ensured that he would take a healthy interest in the Discworld game. He went so far as to rewrite some of Gregg Barnett’s dialog.

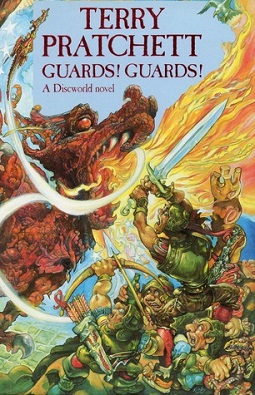

Barnett’s script borrows heavily from Pratchett’s 1989 novel Guards! Guards!. Given how close Watch Commander Sam Vimes, its protagonist, was to his creator’s heart, it must have rankled Pratchett a bit when Barnett elected to write him out of the story, replacing him with Rincewind as chief investigator and player’s avatar. Ditto when Barnett cut out most of the novel’s serious subtext, leaving behind only the gags, jokes, and tropes. And double ditto when the game’s developers eventually cast Eric Idle of Monty Python — a part of the archly absurdist Oxbridge comedy tradition that also included the likes of Douglas Adams, and to which Pratchett did not see Discworld as belonging — to voice the part of Rincewind.

Yet Pratchett was also a reasonable man with a good grasp of what it took to sell creative product, and he could see the logic behind each of Barnett’s decisions. Rincewind was still the series’s most well-known character at this stage in its evolution; serious themes are even harder to bring off in a comic adventure game than they are in a comic novel; and the casting of a real live member of Monty Python in any game was a tremendous coup, even if Eric Idle wasn’t Barnett’s first choice of John Cleese. (According to Barnett, “Fuck off! I don’t do games,” was the latter’s response to his inquiry…) The finished game does absorb some of the flavor of Monty Python — Barnett admits to making the onscreen Rincewind into something of a doppelgänger of Idle’s typically disheveled Python personae — but the combination works. I dare you to try to read a Discworld novel that stars Rincewind after playing this game without hearing Idle’s voice in your head.

The voice-acting cast was rounded out with some other enviable comedic talents: Tony Robinson, Blackadder’s perpetual sidekick; Kate Robbins of Spitting Image; Jon Pertwee, the third incarnation of Doctor Who; and Rob Brydon, a relative newcomer with a prolific career still in front of him (international audiences may know him best today for starring in the very funny Trip series of travel mockumentaries). The only problem with the cast is that there just aren’t enough of them, meaning that everyone with the exception of Idle is juggling many roles, a fact which mugging and accent-switching can’t completely obscure. Still, if one must settle for a cast of less than half a dozen, one couldn’t do much better these actors. It’s a pleasure to listen to the game’s collection of skittish, skeevy, occasionally lovable characters, every single one of them more or less off their nut, prattle on about nothing much in particular. “Is this fish fresh?” Rincewind asks a fishmonger. “Fresh? Fresh?” he replies. “It just made a pass at my wife, sir!”

The game’s visuals are equally distinctive. Under the direction of veteran artist Paul Mitchell, the metropolis of Ankh-Morpork, where the entire game takes place, becomes a Disney film as viewed by a cock-eyed drunk: everything is subtly warped and shifted, with nary a straight line to be seen (or heard, for that matter). Rincewind shuffles from location to location in his bedraggled wizard’s robes, looking like he would rather be anywhere else. (Maybe that’s understandable, given that every other character in the game asks him why he’s wearing a “dress.”) He’s trailed all the time by The Luggage, an inexplicably sentient suitcase with the legs of a centipede, the disposition of a pit bull, and the teeth of a bear trap; this movable feast serves as the means of conveyance of the incredible amount of stuff Rincewind will eventually collect and tote through the city.

As in the novel Guards! Guards!, the plot hinges on a fire-breathing dragon which a cabal of less-than-upstanding Ankh-Morpork citizens have summoned. Thwarting the monster and its minions requires playing through three lengthy, non-linear acts, followed by the climactic showdown with the dragon. Two of the main acts are scavenger hunts: find the five ridiculous things that are needed to build a Dragon’s Lair Revealer; steal the six golden talismans from the dragon-summoning cabal. We’ve all been here before — as has Rincewind apparently, judging from the scorn he is constantly heaping on the whole enterprise. Many adventure games use this sort of self-referential humor as a lazy excuse for derivative, uninspired design, and perhaps Discworld cannot be fully absolved of this sin. It does, however, have the virtue of being much, much funnier than the vast majority of such exercises. And, given that it’s meant to evoke the aesthetic of the early Discworld novels, which lampooned the conventions of paperback fantasy fiction in a similar way, the sin is venal rather than mortal.

Still, the game’s satire is at its best when it aims slightly higher in a meta-fictional sense. The point of the third act is to manipulate circumstances so that Rincewind will have exactly a million-to-one chance against the dragon. Because, as Terry Pratchett himself once put it, “we know — it is built into our very understanding of the narrative universe — that if it is a million-to-one chance that might just work, it will work. Because no one has ever heard of a million-to-one chance that just might work not working. In other words, a million-to-one chance is a certainty. It’s a cliché that we accept. We accept it from James Bond and from Bilbo Baggins.”

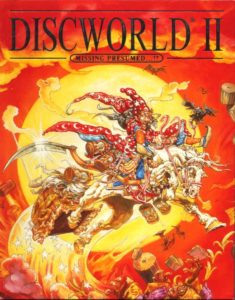

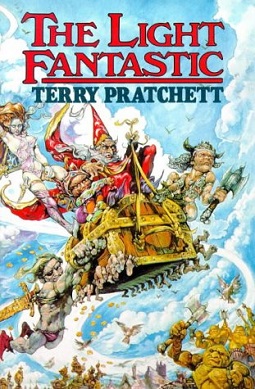

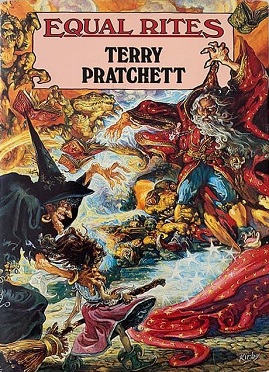

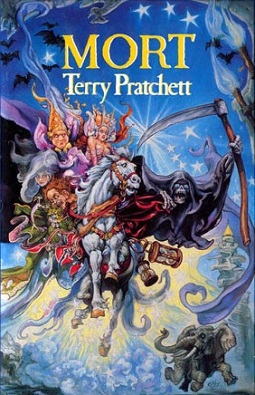

Josh Kirby, Terry Pratchett’s longtime cover illustrator, provided the art for the Discworld game box as well.

Unseen University, where Rincewind has been studying without any obvious benefit to himself or society for years and years.

Death makes a cameo in the first Discworld graphic adventure. He will take a starring role in the second.

Released in Britain in early 1995 under the name of simply Discworld, the game was praised to the skies by reviewer after reviewer. PC Zone magazine wasn’t that much of an outlier in calling it “possibly the best point-and-click adventure game ever made.” Everyone marveled over the graphics, the voice acting, and the humor, declaring that it really was like seeing the world of the novels come to life. Most of all, though, they marveled over the sheer size of the thing. They noted, accurately, that each of the game’s first three acts could easily have been a standalone game in its own right. It was and remains abundantly obvious that the people who made this game did so for all the right reasons, that they genuinely loved Anhk-Morpork and wanted to shove as much of it as possible onto a CD.

Unfortunately, these same people had never actually made an adventure game before. And, once the initial euphoria died down, players could all too plainly see this too in the finished product. It is — or at least ought to be — a truism in adventure design that every puzzle you make is ten times harder than you think it is. The only way to calibrate your game’s difficulty is to put it in front of real players and see how much they struggle. Sadly, it is all too clear that the people who made this game failed to do that in the midst of their zeal to keep adding more, more, more to it.

Discworld is for all intents and purposes insoluble. There is simply no way to reason out many of its puzzles; this is where the cockamamie nature of the world comes back to bite. The designers have paid no heed to what Bob Bates calls the “else” rule of good puzzle design. It states that, if the player has not done the correct thing, but she has done some other thing that might make some degree of logical or comedic sense, the game should recognize and acknowledge that in some way, ideally whilst embedding within its response a hint as to the correct way forward. In this game, though, everything you try to do that isn’t the One True Way Forward is met only by a scornful Eric Idle telling you, “That doesn’t work!” This is the one quote from Discworld that absolutely everyone remembers. Long before you finish the first act, it will have begun to haunt your very dreams, will pop back into your head to enrage you at random moments throughout your day. And just to ensure that you get to hear it even more often than you otherwise might, the game is littered with red herrings that have no purpose whatsoever.

To sum up, then, we have a huge environment to wander around in, one which provides no shortcuts to get from place to place, just Rincewind’s lackadaisical stroll; an enormous pile of objects, many of which are literally good for nothing; puzzles whose solutions are amusing in retrospect but cannot possibly be anticipated before the fact; and no middle ground between wrong and right when it comes to solving them, to provide useful feedback or at least some small dollop of amusement. Oh, and there are also dead ends that you can stumble into without realizing it, after which you’ll get to spend hours banging your head against brick walls even more fruitlessly than usual. As a piece of game design, Discworld is hopeless.

When the game came out in the United States several weeks after its British release, the reviewers there were clearer-eyed, being carried away with neither excitement over the very existence of a Discworld game nor home-country partisanship. Computer Gaming World magazine wrote that “the overall impression the game conveys is not one of richness but one of clutter and surfeit.” It sold in only middling numbers in the American market.

But that was not the case in Britain and much of Europe. There the game sold hundreds of thousands of copies before second takes started to appear in the gaming press and on the Internet, noting belatedly that labeling it “best adventure game of all time” may have been laying it on a bit thick. Needless to say, it was full speed ahead on the sequel.

Before starting on it in earnest, Angela Sutherland and Gregg Barnett finally did the logical thing and merged their two companies together as Perfect Entertainment. The new entity continued to devote the preponderance of its effort to workaday projects for the console market, but the connections forged thereby brought more than financial benefits to the passion projects: both Discworld and its sequel would be ported to the Sony PlayStation and the Sega Saturn, opening up whole new worlds of potential sales. (Their publisher Psygnosis had in fact been bought by Sony in 1993.)

If the first Discworld game is a sad story of good intentions and soaring ambitions derailed by a lack of experience with the nuts and bolts of adventure design, Discworld II: Missing, Presumed…!? is a happier tale of a development team willing and able to learn from their failures — a less common phenomenon than one might expect in the world of adventure games. It doesn’t so much try to break new ground as to perfect the experience which Perfect Entertainment had attempted to deliver last time around. And it succeeds on these terms rather magnificently. Right from the first page of the manual, where they promise that this Discworld game is “a little easier,” the makers make it clear that they understand what they did wrong last time.

Interestingly, Pratchett was less involved with the sequel. “I let them have their heads a bit more,” he said after its release. “It seemed that they could create a game that had the right kind of feel to it, so I didn’t have to shepherd them so much. There wasn’t quite so much shouting this time around.”

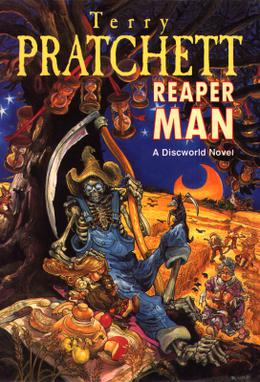

Once again the broad plot is lifted from a beloved Discworld novel: this time it’s 1991’s Reaper Man, in which Death leaves his job and retires to the countryside, with chaotic results for the whole Disc. As in the last game, matters are rejiggered to insert Rincewind into the story as the protagonist, while space is also made for elements of the 1990 Discworld novel Moving Pictures, an entertaining if not particularly deep pastiche of old Hollywood (“Holy Wood” on the Disc), with motion-picture cameras which consist of fast-painting imps trapped inside windowed boxes.

The second game is another joy to listen to; Eric Idle agreed to return, as did Kate Robbins and Rob Brydon. Tony Robinson elected not to, however, while the elderly Jon Pertwee was too ill to participate. (He died in May of 1996, leaving Discworld I as one of his last media legacies.) To take up some of the slack, Perfect hired Nigel Planer, another stalwart comedy veteran, who would go on to narrate almost all of the audio-book versions of the Discworld novels. Barnett tried to recruit Christopher Lee for the role of Death — an inspired choice by any standard — but Perfect couldn’t afford his asking price in the end. So, Rob Brydon took the role instead, and did very well with it, bringing out the mix of fussiness, petulance, and compassion that has since made Death arguably the most popular Discworld character of all time. On the whole, then, the voice acting in Discworld II is on a level with that of the first game — including, alas, the same major weakness of there just not being enough different actors. Kate Robbins, for example, voices every single female character in both games, and most of the children to boot.

The truly striking change from the first game to the second is the look of the production; the difference here is truly night and day. The switchover in the mid-1990s from the VGA graphics standard, with a typical resolution of 320 X 200, to SVGA, with a resolution of 640 X 480 or more, strikes me as the second of the two most dramatic inflection points in the history of computer-game graphics. (The first, for the record, is the arrival of the Commodore Amiga in the mid-1980s, followed soon after by VGA on MS-DOS machines.) The first and second Discworld graphic adventures stand on either side of the VGA/SVGA Rubicon, which divides games that look undeniably old today from those that can at least potentially still look quite contemporary. I would place Discworld II among this group without hesitation.

The higher resolution allowed Perfect to outsource the animation to Hanna-Barbera’s studio in the Philippines, a decision which would have made no sense under the constraints of VGA. Characters and backgrounds that looked a bit muddy and blurry in the first game pop on the screen in sharp, vivid cartoon colors this time around. Meanwhile the static views of the first game are replaced by fades, pans, and close-ups; it’s like going from the typical 1930s film to Citizen Kane.

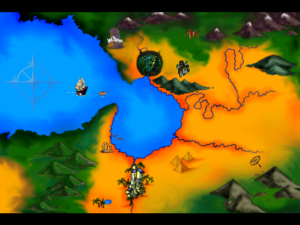

Most importantly of all, Discworld II plays better. We have the same three-act structure as last time, with all of the acts no more than scavenger hunts at bottom. But this time we get to venture beyond Ankh-Morpork to other locations on the Disc. Counterintuitively with this last, the game as a whole is a bit smaller — and yet this is by no means a bad thing. The combinatorial explosion is much reduced, thanks to fewer locations, fewer objects, almost no red herrings, an absence of dead ends, and a much more concentrated effort to calibrate the puzzles to that sweet spot which lies equidistant from the trivial and the impossible. Discworld II isn’t an easy game; its puzzle-dependency chains are sometimes nested a dozen layers deep. Yet it is a soluble one, with puzzles that make a modicum of sense on the vast majority of occasions. Rincewind even deigns to say something other than “That doesn’t work!” some of the time when you try something that, well, doesn’t work. And the world of the game is even more of a delight than last time just to explore, being stuffed to the brim with eccentric characters and curious sights. Meaty, funny, generous, and yet unabashedly traditionalist, it succeeds in actually being everything its predecessor tried but failed to be.

You can move around on a larger world map this time. Notice the Luggage swimming behind Rincewind’s ship.

Oh, my, what’s happened here? In one of the best gags in a game that delights in pulverizing the fourth wall at every opportunity, Rincewind 2.0 gets transported for a few minutes back into the world of Discworld I, where he meets his low-res counterpart.

Thanks to already-built tools and the outsourcing of the animation, Perfect Entertainment was able to finish their second Discworld game in less than eighteen months, and Psygnosis released it in late 1996. By this time the adventure market in the United States was showing undeniable signs of mushiness, but it was still holding up comparatively well in Britain and Germany; Broken Sword, another homegrown British production from Revolution Software, would be a substantial hit that holiday season. Still, a sense of gloom was creeping in even on this side of the Atlantic. Discworld II testifies to this with a considerable amount of gallows humor about its genre. “Aren’t you gonna miss it when they stop making these games?” says Rincewind at one point.

Discworld II did reasonably well in the friendliest markets, but not as well as the first game. And it again made even less of an impact in the United States, despite a gushing review from Scorpia, Computer Gaming World‘s long-tenured, infamously cantankerous adventure columnist. “It’s been too long since I could unreservedly recommend a game,” she wrote. “I can do it now.”

Between its computer and console versions, Discworld II sold just well enough to justify one more game. This would be a brave effort which eschewed the low-hanging fruit of cartoon comedy in favor of a dramatically different direction, enough so as to justify comparisons with Equal Rites, the Terry Pratchett novel which proved that the literary Discworld was more than just a fantasy version of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. We’ll turn to that final Discworld computer game to date, as well as the later years in Pratchett’s life and literary career, in due course, in another article.

For now, though, let me echo Scorpia’s unreserved endorsement of Discworld II. Its predecessor is an interesting but badly flawed creation, best left for hardcore fans of Rincewind who are willing to play with a walkthrough by their side, but the sequel deserves to be better remembered today as the minor classic it is. It represents the Discworld comedy game perfected.

(Sources: the books The Magic of Terry Pratchett by Marc Burrows and Terry Pratchett’s Discworld: The Official Strategy Guide by Glen Eldridge; Starlog of August 1990; CD-ROM Today of April 1995; Computer Gamer of January 1987; Computer Gaming World of June 1995 and May 1997; Computer and Video Games of September 1986; Electronic Entertainment of July 1995; GameFan of September 1997; Next Generation of August 1997; PC Zone of January 1995, August 1996, November 1996, and May 1999; PC Powerplay of November 1996 and July 1997; Sinclair User of December 1986; The One of September 1993; Retro Gamer 94 and 164.

None of the Discworld game are available for legal purchase today, doubtless due to complications with the literary license. Thankfully, Perfect Entertainment’s Discworld and Discworld II are available in ready-to-play Windows versions on The Collection Chamber. Mac and Linux users can import the data files there into their computer’s version of ScummVM.)