I feel fairly confident in stating that Thomas M. Disch trails only Robert Pinsky as the second most respected literary figure to turn his hand to the humble text adventure — speaking in terms of his literary prestige at the time of his game’s release, that is. The need for that last qualifier says much about his troubled and ultimately tragic life and career.

Disch burst to prominence alongside Roger Zelazny and the rest of science fiction’s New Wave in the mid-1960s. Yet Disch’s art was always even more uncompromising — and usually more uncompromisingly bleak — than that of his peers. His first novel bears the cheery name of The Genocides, and tells the story of the annihilation of humanity by an alien race who remake the Earth into a hyper-efficient nutrient farm, apparently without ever even recognizing humans as sentient. In its final scenes the remnants of the human race crawl naked through the innards of the aliens’ giant plants, stripped of even a veneer of civilization, reduced to feeding and fucking and waiting to be eradicated like the unwanted animal infestations they are. Camp Concentration — sensing a theme? — another early novel that is perhaps his most read and most acclaimed today, tells of another ignominious end to the human race, this time due to an intelligence-boosting super-drug that slowly drives its experimental recipients insane and then gets loose to spread through the general population as a contagion.

The protagonist of the latter novel is a pompous overweight intellectual who struggles with a self-loathing born of his homosexual and gastronomic lusts, a man who can feel uncomfortably close to Disch himself — or, more sadly, to the way Disch, a gay man who grew up in an era when that was a profoundly shameful thing to be, thought others must see him. Perhaps in compensation, he became a classic “difficult” artiste; his reputation as a notable pain in the ass for agents, editors, and even fellow writers was soon well-established throughout the world of publishing. He seemed to crave a validation from science fiction which he never quite achieved — he would never win a Hugo or Nebula for his fiction — while at the same time often dismissing and belittling the genre when not picking pointless fights within it with the likes of Ursula Le Guin, whom he accused of being a fundamentally one-dimensional political writer concerned with advancing a “feminist agenda”; one suspects her real crime was that of selling far more books and collecting far more awards than Disch. Yet just when you might be tempted to dismiss him as an angry crank, Disch could write something extraordinary, like 334, an interwoven collection of vignettes and stories set in a rundown New York tenement of the near future that owes as much to James Joyce as it does to H.G. Wells; or On Wings of Song, both a sustained character study of a failed artist and a brutal work of satire in precise opposition to the rarefied promise of its title — these “Wings of Song,” it turns out, are a euphemism for a high-tech drug high. Disch wrote and wrote and wrote: high-brow criticism of theater and opera for periodicals like The New York Times and The Nation; reams of science-fiction commentary and criticism; copious amounts of poetry (always under the name “Tom Disch”), enough to fill several books; mainstream horror novels more accessible than most of his other efforts, which in 1991 yielded at last some of the commercial rewards that had eluded his science fiction and poetry when he published The M.D., his only bestseller; introductions and commentaries to the number of science-fiction anthologies he curated; two plays and an opera libretto; and, just to prove that the soul of this noted pessimist did house at least a modicum of sweetness and light, the children’s novel The Brave Little Toaster, later adapted into the cult classic of an animated film that is still the only Disch story ever to have made it to the screen.

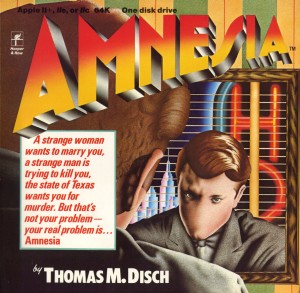

The dawn of the brief bookware boom found Disch at a crossroads. On Wings of Song, published in 1979, would turn out to be his last major science-fiction novel, its poor commercial performance the final rejection that convinced him, the occasional short story or work of criticism aside, to write in other genres for the remaining quarter century of his life. He was just finishing his first horror novel, The Businessman, when his publisher Harper & Row came to him to ask if he might be interested in making his next novel interactive, in the form of the script for a computer game. Like just about every other book publisher in the United States, Harper & Row were in equal measure intrigued by the potential for interactive literature and terrified lest they be left out of a whole new field of literary endeavor. They were also, naturally, eager to leverage their existing stable of authors. Disch, a respected and established author of “literary” genre fiction who didn’t actually sell all that well as a rule, must have seemed an ideal choice; they’d get the cachet of his name without forgoing a bunch of guaranteed sales of a next traditional novel. For his part, Disch was intrigued, and jumped aboard with enthusiasm to write Amnesia.

We know quite a lot about Disch’s plans for the game thanks to a fellow historian named Stephane Racle, who in 2008 discovered his design script, an altogether fascinating document totaling almost 450 pages, along with a mock-up of Harper & Row’s planned packaging in a rare-books shop. The script evinces by its length and detail alone a major commitment to the project on Disch’s part. He later claimed to find it something of a philosophical revelation.

When you’re working on this kind of text, you’re operating in an entirely different mode from when you’re writing other forms of literature. You’re not writing in that trance state of entering a daydream and describing what’s to the left or right, marching forward, which is how most novels get written. Rather, you have to be always conscious of the ways the text can be deconstructed. In a very literal sense, any computer-interactive text deconstructs itself as you write because it’s always stopping and starting and branching off this way and that. You are constantly and overtly manifesting those decisions usually hidden in fiction because, of course, you don’t normally show choices that are ruled out — though in every novel the choices that are not made are really half the work, an invisible presence. With Amnesia, I found myself working with a form that allowed me to display these erasures, these unfollowed paths. It’s like a Diebenkorn painting, where you can see the lines that haven’t quite been covered over by a new layer of paint. There are elements of this same kind of structural candor in a good Youdunit.

Disch came to see the player’s need to figure out what to type next as a way to force her to engage more seriously with the text, to engage in deep reading and thereby come to better appreciate the nuances of language and style that were so important to him as a writer.

Readers who ordinarily skim past such graces wouldn’t be allowed to do that because they’d have to examine the text for clues as to how to respond; they’d have to read slowly and carefully. I thought that was theoretically appealing: a text whose form allowed me a measure of control over the readerly response in a way unavailable to a novelist or short-story writer. I’ve always been frustrated that genre readers are often addictive readers who will go through a novel in one night. I can’t read at that speed — and I don’t like to be read at that speed, either.

Philosophical flights aside, Disch didn’t shirk the nitty-gritty work that goes into crafting an interactive narrative. For instance, he painstakingly worked through how the protagonist should be described in the many possible states of dress he might assume. He even went so far as to author error messages to display if the player, say, tries to take off his pants without first removing his shoes. He also thought about ways to believably keep the story on track in the face of many possible player choices. One section of the story, for example, requires that the player be wearing a certain white tuxedo. Disch ensures this is the case by making sure the pair of jeans the player might otherwise choose to wear have a broken zipper which makes them untenable (this also offers an opportunity for some sly humor, an underrated part of Disch’s arsenal of writing talents). Even Douglas Adams, a much more technically aware writer who was very familiar with Infocom’s games before collaborating with Steve Meretzky on The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, couldn’t be bothered with this kind of detail work; he essentially authored just the main path through his game and left all the side details up to Meretzky.

Amnesia‘s story is not, outside the presence of a drug capable of inducing sustained and ever-encroaching amnesia, science fiction. It’s rather a noirish mystery in which no character, including the amnesiac protagonist, is pure, everyone has multiple layers of secrets and motivations, and nothing is quite what it initially seems. Disch almost seems to have challenged himself to make use of every hoary old cliché he can think of from classic detective fiction, including not only the device of amnesia itself but also hayseed Texans who shoot first and ask questions later, multiple femme fatales, and even two men who look so alike they can pass as identical twins. It takes a very good writer to get away with such a rogues gallery of stereotypes. Luckily, Disch was a very good writer when he wanted to be. Amnesia is not, mind you, deserving of mention alongside Disch’s most important literary works. Nor, one senses, is it trying to be. But it is a cracker of a knotty detective story, far better constructed and written than the norm in adventure games then or now. Among its most striking features are frank and even moving depictions of physical love that are neither pornographic nor comedic, arguably the first such to appear in a major commercial game.

Cognetics — Pat Reilly, Kevin Bentley, Lis Romanov, and Charlie Kreitzberg — trying to be EA rock stars and, with the notable exception of Bentley, failing miserably at it.

To implement his script, Harper & Row chose a tiny New Jersey company called Cognetics who were engaged in two completely different lines of endeavor: developing the user interface for Citibank ATMs and developing edutainment software for Harper & Row, specifically a line of titles based on Jim Henson’s Fraggle Rock television series. The owner of Cognetics, Charlie Kreitzberg, already had quite a long background in computing for both business and academia, having amongst other accomplishments authored a standard programming text called The Elements of FORTRAN Style a decade before. Working with Kreitzberg and others, a Cognetics coder named James Terry had developed an extendible version of the Forth programming language with a kernel of just 6 K or so to facilitate game development on the Apple II. He dubbed this micro-Forth “King Edward” for reasons known only to him. The actual programming of Amnesia he turned over to a local kid named Kevin Bentley; they had met through Kreitzberg’s wife, who shopped at the grocery store owned by Bentley’s family. And so it was poor young Kevin Bentley who had Disch’s doorstop of a script dropped on his desk — no one had apparently bothered to tell the untechnical Disch about the need to limit his text to fit into the computers of the time — with instructions to turn it into a working game. He had nothing to start with but the script itself and that 6 K implementation of Forth; he lacked even the luxury of an adventure-specific programming language like ZIL, SAL, AGI, or Comprehend.

It was of course a hopeless endeavor. Not only had Disch provided far, far too much text, but he’d provided it in a format that wasn’t very easy to work with. Disch, for understandable reasons, thought like a storyteller rather than a world builder. Therefore, and in the absence of other guidance, he’d written his story from the top down as essentially a hypertext narrative, a series of branching nodes, rather than from the bottom up, as a set of objects and rooms and people with descriptions of how they acted and reacted and how they could be manipulated by the player. Each part of his script begins with some text, followed by additional text passages to display if the player types this, that, or the other. Given the scope of possibility open to the player of a parser-driven game, that way lies madness. We’ve seen this phenomenon of text adventures that want to be hypertext narratives a surprising number of times already on this blog. Amnesia is perhaps the most painful victim of this fundamental confusion, born of an era when hypertext fiction didn’t yet exist outside of Choose Your Own Adventure books and any text- and story-driven game was assumed to necessarily be a parser-driven text adventure.

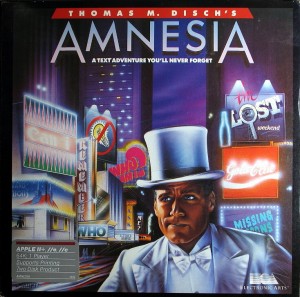

In mid-1984, just as it was dawning on Cognetics what a mouthful of a project they’d bitten off, Harper & Row, the instigators of the whole thing, suddenly became the first of the big book publishers to realize that this software business was going to be more complicated than anticipated and, indeed, probably not worth the effort. (The depth of the blasé belief of which they were newly disabused that software publishing couldn’t be that hard is perhaps best measured by the fact that they had all of the box art for Amnesia prepared before Cognetics had really gotten started with the actual programming, evidently thinking that, what with Disch’s script delivered, it couldn’t be long now.) They abruptly pulled out, telling Kreitzberg he was welcome to do what he liked with Fraggle Rock and Amnesia. He found a home for the former with CBS, another old-media titan still making a go of software for the time being, and for the latter with Electronic Arts, eager to join many of their peers on the bookware bandwagon. EA producer Don Daglow was given the unenviable task of trying to mediate between Disch and Cognetics and come up with some sort of realizable design. He would have his hands full, to such an extent that EA must soon have started wondering why they’d signed the project at all.

In addition to being a noir mystery, Disch had conceived Amnesia as a sort of extended love letter to his adopted home of Manhattan. Telarium’s Fahrenheit 451, when released in late 1984, would also include a reasonably correct piece of Manhattan. Disch, however, wanted to go far beyond that game’s inclusion of twenty blocks or so of Fifth Avenue. He wanted to include almost all of the island, from Battery Park to the Upper West and East Side, with a functioning subway system to get around it. The resulting grid of cross-streets must add up to thousands of in-game locations. It was problematic on multiple levels; not only could Disch not possibly write enough text to properly describe this many locations, but the game couldn’t possibly contain it. Yet Disch, entranced by the idea of roaming free through a virtual Manhattan, refused to be disabused of the notion. No, EA and Cognetics had to admit, such a thing wasn’t technically impossible. It was just that this incarnation of Manhattan would have to be 99 percent empty, a grid of locations described only by their cross-streets, with only the occasional famous landmark or plot-relevant area poking out of the sea of nothingness. That’s exactly what the finished game would end up being, rivaling Level 9’s Snowball for the title of worst ratio of relevant to irrelevant locations in the history of the text adventure.

The previous paragraph underlines the most fundamental problem that dogged the various Amnesia teams. Disch never developed with Cognetics and EA the mutual respect and understanding that led to more successful bookware collaborations like Amazon, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and Mindwheel. Given the personality at the center of Amnesia, that’s perhaps not surprising. I described Disch as “difficult” earlier in this article, and, indeed, that’s exactly the word that Kevin Bentley used to describe him to me. His frustration with the collaboration was still palpable when I recently corresponded with him.

The conclusion I reached was that Tom wanted to write a book and have it turned into a game by creating a sort of screenplay adapted from a book. The trouble was that a screenplay to my mind was the wrong metaphor for an adventure game. The missing piece of the puzzle seemed to be that Tom didn’t grasp that an adventure game was a matrix of possibilities and it was up to the user to discover the route, and the point was not to cram the user toward the “conclusion.” Tom was very unhappy with the notion that the player might not experience the conclusion of the story the way that he intended in the script, so he insisted that the user be directed toward the conclusion.

Bentley and Kreitzberg met with Disch just a handful of times at his apartment near Union Square to try to iron out difficulties. The former remembers “lots of herbal tea being offered,” and being enlisted to fix problems with Disch’s computer and printer from time to time, but it’s safe to say that the sort of warm camaraderie that makes, say, the Mindwheel story such a pleasure to relate never developed. Before 1984 was out, frustrated with the endless circular feedback loop that the project had become and uninterested in the technical constraints being constantly raised as issues by his colleagues, Disch effectively washed his hands of the whole thing.

His exit did allow EA and Cognetics a freer hand, but that wouldn’t necessarily turn out for the better. Feeling that the game “was lacking in the standard sorts of gaming experience (like a score, sleep, food, etc.)” and looking for some purpose for that huge empty map of Manhattan, EA requested that Bentley shoehorn all that and more into the game; the player would now have to eat and sleep and earn money by taking odd jobs whilst trying to come to grips with the central mystery. The result was a shotgun marriage of the comparatively richly implemented plot-focused sections from Disch’s original script — albeit with more than half of the text and design excised for reasons of capacity — with a boring pseudo-CRPG that forces you to spend most of your time on logistics — earning money by begging or washing windows or doing other odd jobs, buying food and eating it, avoiding certain sections of the city after dark, finding a place to sleep and returning there regularly, dealing with the vagaries of the subway system — all implemented in little better than a Scott Adams level of detail. Daglow came up with an incomprehensible scoring system that tries to unify all this cognitive dissonance by giving you separate scores as a “detective,” a “character,” and a “survivor.” And as the cherry on top of this tedious sundae, EA added pedestrians who come up to you every handful of moves to ask you to look up numbers on a code wheel, one of the most irritating copy-protection measures ever implemented (and that, of course, is saying something).

All of this confusion fell to poor Kevin Bentley to program. He did a fine job, all things considered, even managing a parser that was, if not up to Infocom’s standards, also not worse than its other peers. Nevertheless growing frustrated and impatient with the game’s progress, EA put him up in an “artist apartment” near their San Mateo, California, headquarters in February of 1985 so that he could work on-site on a game that was now being haphazardly designed by whoever happened to shout the loudest. He spent some nine months there dutifully implementing — and often de-implementing — idea after idea to somehow make the game playable and fun. Bentley turned in the final set of code in November of 1985, by which time “everyone was over it,” enthusiasm long since having given way to a desire just to get something up to some minimal standard out there and be done with it. Certainly Bentley himself was under no illusions: “as a game I thought it sorta bombed.” Impressed with his dogged persistence, EA offered him a job on staff: “But I was 20 and far from home. I knew if I left immediately and drove back to New Jersey I could be home for Thanksgiving.” Unsurprisingly given the nature of the experience, Amnesia would mark the beginning and the end of his career as a game developer. He would go on to a successful and still ongoing career in other forms of programming and computer engineering. Charlie Kreitzberg and Cognetics similarly put games behind them, but are still in business today as a consulting firm, their brief time in games just a footnote on their website.

EA’s released Amnesia package. Note that it’s simply called a “text adventure,” a sure sign that the bookware boom with its living literature and electronic novels has come and gone.

Amnesia, a deeply flawed effort released at last only during the sunset of the bookware boom, surprised absolutely no one at EA by failing to sell very well. It marks the only game EA would ever release to contain not a single graphic. Contemporary reviews were notably lukewarm, an anomaly for a trade press that usually saw very little wrong with much of anything. Computer Gaming World‘s Scorpia, admittedly never a big fan of overtly literary or experimental games, issued a pithy summary that details the gist of the game’s problems.

Overall, Amnesia is an unsatisfying game. You can run around here, and run around there, and work up your triple scores as a detective, a character, and a survivor, but so what? Much of what you actually do in the game doesn’t get you very far towards the ultimate solution. Boiled down to the essentials, there are only three things you need to do here: follow up on the clue from TTTT, get and read the disk, and meet Bette. There are auxiliary actions associated with them, but those are the key points. So when you think back on the game as a whole, you don’t see yourself as having done, really, a whole lot, as having been the main character. It’s more as though you came to certain places in a book, and turned a page to get on with the story.

Bottom line: terrific prose, nice maps, too much novel, not enough adventure.

Disch, despite having walked away from the hard work of trying to make the game better over a year before its release and despite having probably never even played the version of Amnesia which arrived in stores, took such reviews predictably personally. Amnesia, he pronounced, had been “one of the quickest disillusionments of my life.” He went on to blame the audience.

The real problem is that there’s simply no audience for this material, no one who would respond enthusiastically to what I do well. Those who buy it, who are aficionados of the form, are basically those who want trivial pursuits; and to offer them something, however entertaining, that involved reading and imaginative skills they did not care to exercise while playing with their computers was foolish. I felt like de Soto, who journeyed to Tennessee looking for the Fountain of Youth — an interesting enough trip, but neither of us found what we were looking for.

People who want to play this sort of game are looking, I suppose, for something like Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker, where they can have their familiar experiences replayed. The computer-interactive games that have done well — like the Hitchhiker’s or Star Trek series — have been tied in with copyrighted materials that have already had success with the target audience in prior literary forms. I don’t think the quality of those scripts compares to what I did in Amnesia — Adams’s scripts, for example, are actually very good of a kind, but it’s a matter of one little joke after another. The notion of trying to superimpose over this structure a dramatic conception other than a puzzle was apparently too much for the audience. In the end, I just produced another literary curiosity.

There’s more than a grain of truth in all this if we can overlook the condescension toward Douglas Adams that would be more worthily applied to one of his derivatives like Space Quest. A computer-games audience more interested in the vital statistics of dragons and trolls than the emotional lives of the socially engaged humans around them undoubtedly did prove sadly unreceptive to games that tried to be about something. And reviewers like Scorpia did carry into their columns disconcertingly hidebound notions of what an “adventure game” could and should be, and seemed to lack even the language to talk about “a dramatic concept other than a puzzle,” to the extent that Scorpia’s columns on Infocom’s two most forthrightly literary works, A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity, are little more than technical rundowns and catalogs of puzzle hints — not to mention her reaction to one of Infocom’s first bold literary experiments, the ending to Infidel — and poor Brian Moriarty found himself actively playing down the thematic message of Trinity in interviews in the hope of actually, you know, selling some copies of this supposedly “depressing” game. It’s just that Amnesia, being well-nigh unplayable, is an exceedingly poor choice to advance this argument, and for that Disch deserves his due share of the responsibility. At some level, having just served up — or having at least allowed his name to be attached to — a bad game, he’s not entitled to this argument.

Disch’s ultimate fate was an exceedingly sad one. After the millennium, his world crashed around him brick by brick. First there was the shock of witnessing the September 11 attack on his beloved New York, a shock that seemed to break a circuit somewhere deep inside him; often open to charges of nihilism, extreme pessimism, even misanthropy during his earlier career, it wasn’t until after September 11 that his hatred for the people who had done this made him begin to sound like a bigot. Then in 2005 Charles Naylor, his partner of three decades, died. In the aftermath came an effort by his landlord to evict him from the rent-controlled apartment the two had shared, an effort which appeared destined for success. With his writing career decidedly on the wane, his books dropping out of print one by one, and his income correspondingly diminishing, he did most of his writing after Naylor’s death in his LiveJournal blog. Amidst the poorly spelled and punctuated screeds against Muslim terrorists and organized religions of all stripes, depressingly similar to those of a million other angry bloggers, would come the occasional pearl of wisdom or poetry to remind everyone that somewhere inside this bitter, suffering man was the old Thomas M. Disch. And suffer he did, from sciatica, arthritis, diabetes, and ever-creeping obesity that left him all but housebound, trapped alone in his squalid apartment with only his computer for company. On July 4, 2008, he ended the suffering with a shotgun. In 1984, for Amnesia, a younger Disch had written from that same apartment that “suicide is always a dumb idea.” Obviously the pain of his later years changed his mind.

One of the writers with whom Disch seemed to feel the greatest connection was another brilliant, difficult man who always seemed to carry an aura of doom with him, and another who died in tragically pathetic circumstances: Edgar Allen Poe. Disch once wrote a lovely article about Poe’s “appalling life,” the last year of which “seems a headlong, hell-bent rush to suicide.” Like Disch, Poe also died largely forgotten and unappreciated. Perhaps someday Disch will enjoy a revival akin to that of Poe. In the meantime that Amnesia script sits there tantalizingly, ripe as ever to become a modern work of interactive fiction that need not leave out a single word, that could give us Disch’s original vision undiluted by scores and copy protection and money problems and hunger and sleep timers. Maybe he’d forgive us for trimming some of that ridiculous Manhattan. And maybe, just maybe, his estate would be willing to give its blessing. Any takers?

A Long Overdue Update, March 13, 2023: My old mentor Dene Grigar and the rest of the Electronic Literature Lab at Washington State University Vancouver took up the challenge of bringing Amnesia into the 21st century, working from Disch’s original script! Also check out the book Amnesia Remembered: Reverse Engineering a Digital Artifact by John Aycock.

(First and foremost, huge thanks to Kevin Bentley for sharing with me much of the history of Cognetics and Amnesia. Disch himself talked about Amnesia at greatest length in an interview published in Larry McCaffery’s Across the Wounded Galaxies: Interviews with Contemporary American Science Fiction Writers. Disch’s writings on science fiction are best collected in the Hugo-winning The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of and On SF. Scorpia’s review of Amnesia appeared in the January/February 1987 Computer Gaming World.

I’ve made Amnesia available here for download in its MS-DOS incarnation with a DOSBox configuration file that works well with it. Note that you’ll need to use the file “ACODES.TXT” in place of the code wheel when the irritating pedestrians start harassing you.)