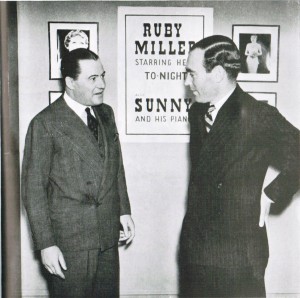

As a fellow very concerned about his place in society, Dennis Wheatley carefully cultivated friendships with quite a number of people, enough so that one kind of wonders where he found time to maintain his prodigious literary output. One of the most surprising of these was an up-and-comer named Joseph Gluckstein Links, or just “Joe” to friends like Wheatley.

Born in 1904, Links was, like Wheatley, the son of a tradesman. But the similarities ended there. Links’s father was a Jewish refugee from Hungary who owned a business that served the bottom end of the fur trade, dealing in skunk. Links didn’t have the opportunities Wheatley did to finish his education and indulge his whims as a young man-about-town in London. His mother died when he was twelve, and two years later his father learned that he was also terminally ill. With no time to spare, he pulled young Joe out of school to give him a rush course on the fur trade in general and the business he would soon need to run. “I was a sullen and unwilling pupil,” Links later wrote, but “there was the business and I jolly well had to go and earn my living at it.”

Links turned out to be possessed of a shrewd business sense. And, after such an ill-starred childhood, he was lucky at last. Fur, whatever ethical dilemmas it raises today, was exploding in the fashion world of the time; every girl wanted a fur coat, more than one if she could get them. Links was able to move his firm, Calman Links, upscale to meet this demand. Even the Great Depression didn’t stop him. By the 1930s London was the epicenter of a booming luxury fur trade, and Calman Links was one of its most prominent furriers.

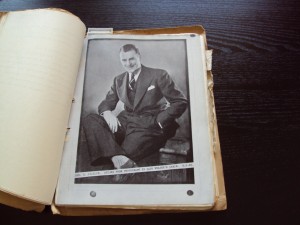

As a young man Links was a friend of Nancy Robinson, the wealthy heiress to the Nugget Boot Polish fortune who, in something of a social-climbing coup for Wheatley, became his wife in 1922. It was through Nancy that the two men met, but their relationship far outlasted Wheatley’s first marriage, which ended in 1930. It was a surprising friendship because Links was Jewish; in common with so many in the British Right of this period, there was a strong streak of anti-Semitism in Wheatley’s early novels. Still, Links was urbane, cultured, witty, and discreet, and, as you might expect from one who made his living through fashion, known everywhere as a very snappy dresser. Despite his humble origins and limited education, all of this seemed to come to him effortlessly. Indeed, one might say that Links was a more natural, authentic version of the man that Wheatley worked so hard throughout his life to be. He also shared Wheatley’s taste for luxury, most notably in the form of good cigars and expensive wines. He cut such an impressive figure that not only Wheatley but most of his social circle were willing to forgive him his ethnicity. The friendship was perhaps really cemented as a lifelong one during the personal crisis that precipitated Wheatley’s becoming a writer. At this critical time Links was a huge source of comfort and support, lending Wheatley money to pay his creditors and his lawyers and a secluded cottage to get away from it all and pull his first novel together.

One night over dinner, circa 1935, Links dropped a brainstorm on Wheatley: what if they put together a murder mystery not in the form of a novel but rather as a dossier of reports and clues? Since so much of contemporary crime fiction was really about giving the reader a puzzle to solve, the trappings of the novel were beginning to seem to Links like a pointless intrusion on their real appeal. “Why can’t we just have the facts and the clues?” he theorized readers must be asking.

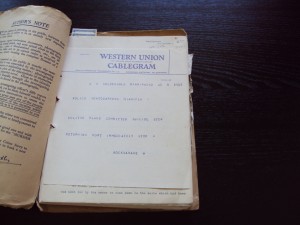

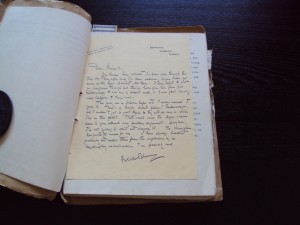

There had been some attempts before to present mysteries explicitly as puzzles to be solved. In 1928, Lassiter Wren and Randle McKay published the first Baffle Book, consisting of the brief descriptions of fifteen cases that the reader was expected to solve from the clues in the text. These cases read, however, like generic sketches of mystery plots before the scenery and characters were painted in, and thus played more like abstract logic puzzles than participatory mysteries. Links proposed giving readers all the atmosphere and detail of a full-fledged mystery novel, but explicitly asking her to do what had only been implied in the novels for years now: to solve the crime herself. Further, he imagined including much more than text: physical props, the actual pieces of evidence — what a later generation would come to call “feelies” — would be a key component. The dossier would end with a sealed section containing the solution, which the reader should only open when she believed she had solved the case for herself.

Wheatley was for a time unconvinced. Links was a businessman with no background in writing (or game design, for that matter). As for him, he was a writer, of course, but also a very busy one already selling plenty of books, and he had no experience or following in the already overstuffed genre of detective novels. But Links persisted, and Wheatley was finally taken with the same enthusiasm, with the rare opportunity to do something really, truly new. He took the idea to his publisher, Hutchinson. They were, unsurprisingly, very lukewarm. Producing and stuffing the dossiers with all those physical clues, not to mention typesetting telegrams, handwritten letters, and police reports, would be like nothing they had ever done before — and expensive. Yet Wheatley persisted. He was a very valuable author whom it behooved Hutchinson to keep happy, so at last they agreed — on the condition that Links and Wheatley would be willing to accept no royalties at all on the first 10,000 copies sold, and just one penny per copy after that. It’s a marker of how excited Wheatley was by the project that he agreed; he was normally always very careful to get everything financially coming to him. And so Links and Wheatley set to work, Links planning out the mystery and devising the clues and Wheatley writing the actual text. The dossier would be credited to Wheatley, with a “planned by J.G. Links” blurb inserted in smaller letters. The credits should probably have been reversed; Links had the original idea, after all, and the case at root was apparently his. Still, Links was a very private man happy to continue his life of relatively anonymous privilege. And, more practically, Wheatley’s name definitely sold books.

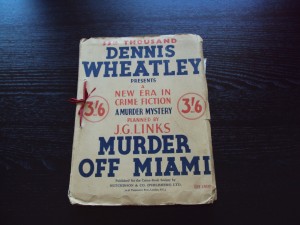

The result was published on July 23, 1936, as Murder off Miami.

A pleasure yacht, the Golden Gull, has just left Miami for a few days of cruising when one of the passengers, a soap magnate named Bolitho Blaine, apparently commits suicide, leading the yacht to return to port just hours after it left. You follow along with the investigation of the detective who meets the boat — through interviews, on-the-scene hunting for physical evidence, etc. In best golden-age-detective-fiction fashion, it quickly transpires that not only was Blaine murdered, but virtually everyone else on the boat has both Dark Secrets to hide and a plausible motive for wanting Blaine dead.

Detective fiction wasn’t Wheatley’s normal gig, but in an odd way he was suited for it, and probably could have done pretty well at it in an alternate reality. Much as he loved to play the cultured libertine, there was also a fussy, detail-oriented side to his personality. Sometimes the two came together in revealing if unappealing ways. His biographer Phil Baker describes a careful list he kept as a young man of every woman he had any sort of amorous contact with, from prostitutes (lots of these) to one-night-stands to proper girlfriends, along with dates and locations and a neat check next to those with which he went all the way. (When he forgot — or never had — names, he just used a shorthand description of the girl.) In Murder, he goes endlessly over suspects and times and locations and alibis, reveling in all this careful, systemic detail in an almost hackerish way; in still another reality, he might have been drawn to programming. If it is hardly revolutionary for a story of its time and genre, the solution to Murder is reasonable (at least by whodunit logic) and satisfying enough, requiring some out-of-the-box thinking that probably comes easier to people steeped in golden-age detective fiction than it did to my wife and me. We came up with a suspect based on an alibi of which the in-story detective seemed a little too trusting, but the answer of course turned out to be something else entirely.

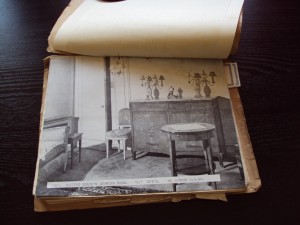

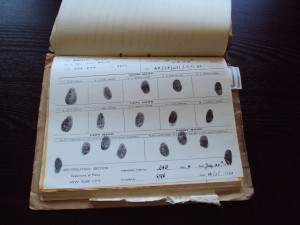

Still, the striking aspect of Murder off Miami is not the case but how it’s presented. In addition to more prosaic text, the dossier contains telegrams, handwritten notes (some of which we had a devil of a time deciphering), photos of crime scenes and suspects, suspect police records, even a blood-stained swatch of curtain.

Like all of Wheatley’s work it’s almost defiantly of its time. For instance, there’s a poor Japanese fellow on the yacht whom no one deigns to call by his real name. He’s just “the Jap,” whom our detective hero warns not to try his “Oriental mind games” on him. Yet it’s still an interesting and unique experience today, even divorced from its historical importance. My wife and I had a lot of fun with it, even if we did fail to crack the case in the end.

Murder off Miami wasn’t something anyone knew quite how to classify. Is it a book or a game? asked reviewers and editorialists in articles that presage some of the discussion that would later swirl around the interactive fiction of Infocom and others. Luckily, Wheatley, you’ll remember, was “very good at selling” books; he tirelessly wined and dined top book buyers during the lead-up to publication to convince them to stock the dossier. Despite no real promotion other than that personally undertaken by Wheatley, Murder off Miami became a minor sensation. It ended up selling over 200,000 copies in Britain in its first year, and was eventually translated into many other languages. Always the royal watcher, Wheatley was delighted to learn that Queen Mary herself bought six copies. Naturally, Links and Wheatley soon set to work on another.

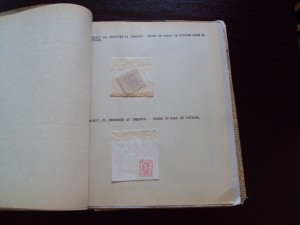

That second dossier, Who Killed Robert Prentice? (1937), is a particularly cold-blooded little number, and as comically dated as ever. Links and Wheatley have fallen afoul of the 1930s rage for Adlerian psychology; the murder victim is defined as a walking, talking bundle of inferiority complexes. Yet the case is more believable and more interesting. Solving it is a three-step process this time, of which my wife and I managed to get two correct. The evidence, meanwhile, is even more impressive than in the first dossier, including more physical props like railway tickets and stamps.

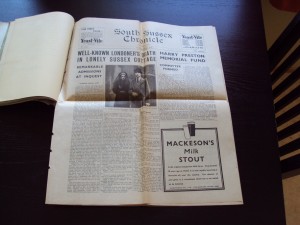

Some of the letters this time were even scented with unique perfumes, providing vital clues about their origins; sadly, this element didn’t survive its journey down through the years to us. Links and Wheatley also show a willingness to get more playful with the format. The centerpiece of the second dossier is a big fold-out newspaper that features not only articles about the case but also real advertisements from various sponsors, another demonstration of Wheatley’s nose for moneymaking opportunities.

There’s also an interview in the newspaper with Wheatley and Links themselves, who do discuss whom they think might have done the crime, but which Wheatley mainly uses as a platform to plug his books. The third dossier would continue to take advantage of Wheatley’s near celebrity in Britain, using him as a character in his own stories in a very postmodern sort of way that’s surprising for this time and this author.

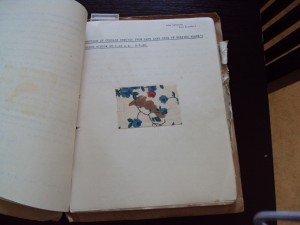

Robert Prentice‘s most risque clue was a torn-up photograph of the victim cavorting with a naked woman. The reader had to assemble this, jigsaw-style, in a way that a later generation would soon be doing in a thousand graphic adventures.

The dossiers were not easy to assemble. During the height of the dossier boomlet, Hutchinson’s employed forty girls to cut swatches out of fabric and stain them, spray perfume on letters, tear corners off of envelopes, and, yes, rip up risque photographs. This hand-assembled aspect of the dossiers gives them an additional appeal today; every one is at least a little bit unique.

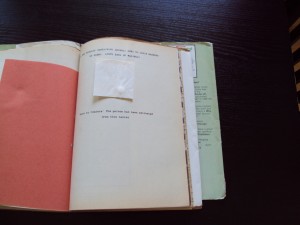

Robert Prentice was another sizable hit, thus spawning a third dossier for 1938, The Malinsay Massacre. Conventional wisdom holds that this is the point where the series began a dramatic decline in quality, but we didn’t really see that. It is true that the feelies have been dramatically reduced in number, to just one, an allegedly poisoned tablet. Still, said tablet is one of the most impressive of all the feelies. If one eats this tablet, one apparently learns an important clue: that it tastes like peppermint. (We weren’t going to try it after all these years and all the hands it must have passed through…)

The photos in Malinsay do look a bit low-rent, which apparently caused some conflict between the partners. Links managed the photo-shoot while Wheatley was out of town. The location he chose, a local hotel, doesn’t much look like the ancestral Scottish castle where the mystery plays out. Wheatley was very unhappy with the results upon his return.

While the rest of the third dossier contains nothing as impressive as the mock-newspaper from the second, we found the mystery itself the most believable and compelling of all — and, with a bit of thought and care, very solvable. We got this one pretty much right, a very satisfying experience. I’d imagine the experience we had with Malinsay came the closest to what Links and Wheatley envisioned when they first started thinking about making the dossiers.

About the fourth dossier, alas, the conventional wisdom is correct. In reaction to grumblings about the dearth of feelies in the previous dossier, the pair went in the other direction this time: “Five times as many clues as in any of the previous dossiers!” the cover trumpets. Unfortunately, that’s about all it’s got going for it. Produced with much less involvement from Wheatley, who was both ill at the time and getting somewhat tired of the exercise, Herewith the Clues sadly lacks his talent for weaving an interesting potboiler narrative. It has far less text than any of the other dossiers, and is the most explicitly gamelike of them all, reading more like the logic-puzzle mystery stubs of Wren and McKay than Wheatley and Links’s previous dossiers. The whole devolves into deciding which of a group of suspects can be identified as having been in a certain room at a certain time; the one who was not present must be the murderer. For the first time a scoring system is provided along with multiple sheets of paper to record your conclusions, so that “each member of the family may fill one up.” Some of the solutions are made more difficult by the cultural gulf between then and now:

Carlotta Casado can be eliminated because: Exhibit E, a sheet of Papier Poudre, Rachel shade, was found in the waste-paper basket. Carlotta is a black-haired Spaniard, with a sun-tanned skin; and none of the other women in the group even approaches a brunette type. Therefore, the Rachel shade sheet of Papier Poudre must have been used by her.

The “Papier Poudre” just looked like a blank square of stiff paper to us, and otherwise we have no idea what any of that is on about.

Other times the solutions are just stupid. Clever, but stupid.

Mug Masters can be eliminated because: Exhibit F, a screw of plain paper found in the waste-paper basket, has invisible writing on it, which at once becomes apparent if the paper is dipped in water. The writing is a personal note to Masters summoning him to the full group meeting to be held on the night of the 23rd; so obviously it was he who threw this paper into the waste-paper basket in the secret room.

Who the hell would start immersing their clues in water? We didn’t spend too much time on trying to solve this one, and when we flipped to the solution and saw stuff like that we were decidedly glad we hadn’t.

Herewith the Clues was published at a fraught historical moment, just six weeks or so before the outbreak of World War II. For all its flaws as a story and game, it’s perhaps even more interesting than the earlier dossiers as a time capsule, an artifact of a proudly snobbish upper-class London social set that was about to be changed forever by war and by the welfare state that would follow. Wheatley being Wheatley, he’s unable to resist breaking the fourth wall in the caption below the picture of each suspect to announce who is really shown there: lords, ladies, and respected society figures all.

When the war began, that was it for the dossiers. All went out of print, and, whatever appeasement sympathies they may have held in earlier lives, Links and Wheatley both joined up and devoted all their energies to the war effort. After the war, the time that had spawned the dossiers seemed to have passed. Agatha Christie’s continuing popularity aside, the detective novel changed again, away from the puzzle-box designs of the golden age to works that again placed more emphasis on realism and literary nuances. The idea of the mystery as an implied game between author and reader moved again into the background, and Wheatley went back to writing his thrillers and his occult pastiches, with only one more detour into ludic mystery. In 1953 he published a board game called Alibi, which appears to have played like a more sophisticated, narrative-rich version of the family staple Cluedo (Clue in North America). It seems that Alibi was not a success, and copies are extremely rare today. I thus don’t know much more about how it played.

Links, meanwhile went back to the fur business — and to a remarkable new career. A longtime bachelor, he finally married just as the war ended. The couple traveled to Venice for their honeymoon. Links fell in love with the city and with one of its famous sons, the landscape painter Canaletto. Over the years that followed Links cultivated both passions. Showing again that talent for moving in circles where he had by all rights no business going, this fellow who had quit school at fourteen and never attended a single class at university became perhaps the world’s foremost expert on Canaletto, writing books, speaking at countless academic conferences, and curating major exhibitions. He also wrote what has sometimes been called the greatest travel guidebook ever written, Venice for Pleasure (1966). He died in 1997 after what was by all accounts a long, varied, happy, and always discreet life.

As a major commercial success, at least in its earlier incarnations, the Wheatley/Links dossier series spawned some imitators. Most notably, William Morrow in the United States republished the first dossier as Crime File Number 1: File on Bolitho Blane, then continued the series with at least three more Crime Files written by American mystery writers. It’s worth speculating what might have happened to the budding genre had World War II not come along to disrupt it. As it was, though, the genre was not resumed after the war, going into history as a curiosity and a footnote to the careers of Wheatley and Links.

Until about 1980, that is. By that time, with the rise of Dungeons and Dragons, Adventure, and the Choose Your Own Adventure line of children’s books, the idea of this sort of blending of story and game was again beginning to feel in step with the times. Hutchinson published new editions of all four dossiers to modest press notices and modest sales. After a few years, they fell out of print again. However, during that brief window when they were easily available once more, a fair number of contemporary creators found them inspiring. In an obvious response to them, Simon Goodenough published a series of three new dossiers based on Sherlock Holmes stories. You can also see a lot of the Wheatley/Links dossiers in a pair of detective board games published originally around this time by Sleuth Publications, Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective and Gumshoe. A bit later two of the dossiers would be directly adapted into rather uninspiring computer games.

But most significantly for our purposes, one Marc Blank of Infocom picked them up, and was inspired to create Deadline, as dramatic a literary leap forward for digital ludic narrative as Zork had been a technical. Having ended this little detour into the 1930s, we’ll pick up with that next time.

(I owe huge thanks for this article to Zack Urlocker, who dug up editions of all four of the Wheatley/Links dossiers from his personal collection, shipped them to me in Norway, and refused to let me pay for any of it. Thank you again, Zack!)