It’s disarmingly easy to underestimate Titanic: Adventure Out of Time, by far the best-selling game in history about the doomed luxury liner. At first glance, after all, it looks like just another of the lifeless multimedia Myst clones that were cluttering up store shelves in such quantities in the mid-1990s. Meanwhile the studio behind it was known as CyberFlix, a name which positively reeks of the era when equally misbegotten “interactive movies” were all the rage. And indeed, CyberFlix really was founded by folks convinced that the future of games would be a collision between Hollywood and Silicon Valley.

But the prime mover behind the operation, a 30-something Tennessean named Bill Appleton, wasn’t just another of the clueless bandwagon jumpers who were using off-the-shelf middleware packages like Macromedia Director to cobble together dodgy games where the video clips took center stage and the interactivity was an afterthought. On the contrary, Appleton knew how to make innovative technology of his own, and had a lengthy resumé to prove it. His early software oeuvre was the ironic polar opposite of interactive movies, those ultimate end-user products that seemed designed to convince the human being behind the monitor that she couldn’t possibly create anything like this. In the beginning, Appleton was all about empowering people to make stuff for themselves.

A youthful overachiever from Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Appleton studied painting and philosophy at university before settling on economics. He was weeks away from earning his master’s degree in that field from Vanderbilt University in the spring of 1984, when he saw an Apple Macintosh for the first time. Like any number of other curious minds who hadn’t heretofore taken much interest in computers, he allowed all of his plans for his life to be utterly derailed by the encounter. He dropped out of university, moved back into his parents’ basement, and rededicated his life to making the Mac do amazing things.

He created an adventure game called Enchanted Scepters, which combined vestiges of the text adventures that were popular on other platforms at the time with simple pictures, sounds, and mouse-driven interactions. In this sense, it was similar to such other early Mac graphic adventures as ICOM Simulations’s Deja Vu, although considerably less refined. The real stroke of genius came when Appleton, a year after releasing the game itself through a small publisher called Silicon Beach Software, packaged up all of the tools he had used to make it and released them as well, under the name of World Builder. The do-it-yourself toolkit spawned a small but dedicated amateur community of adventure makers and players that persisted well into the 1990s. Appleton also adapted World Builder into another product called Course Builder, aimed at educators who wanted to create interactive experiences for the classroom.

With its ethos of empowering a fairly non-technical end user to create original multimedia content, Course Builder especially was veering into the territory soon to be staked out by HyperCard, Apple’s own revolutionary hypertext-authoring system. It’s thus no surprise that, when that software did debut in 1987, Appleton first greeted it as a threat. He quickly decided, however, to adopt the old adage of can’t beat ’em, join ’em — or rather enhance ’em. He moved to Silicon Valley, took control of a team of programmers hired by Silicon Beach Software, and made SuperCard, a system that could run existing HyperCard “stacks” as-is, but that added a whole slew of additional native features to the environment. It attracted some interest in the Macintosh world, but proved unable to compete with HyperCard’s huge existing user base, the result of being bundled with every single new Mac. So, Appleton turned back to games. Hooking up with a Chicago-based developer and publisher called Reactor, he made a beat-em-up game in the tradition of Karateka called Creepy Castle, then embarked on an action-packed 3D extravaganza called Screaming Metal, only for Reactor to go out of business midway through development.

It was thus a thoroughly frustrated Bill Appleton who returned to Tennessee in 1992. His eight years in software had resulted in a pair of cults in the form of the World Builder and SuperCard communities, but he hadn’t ever managed to hit the commercial bullseye he was aiming for. He was a man of significant ambition, and the status of cult hero just wasn’t good enough for him. “I’ve built a lot [of programs] for Silicon Valley,” he said, then went on to air his grievances using the precious diction of a sniffy artiste: “This isn’t about money or power or technology. It’s about art. I’m an artist, and I’ve got to be able to control my work.” Like Bob Dylan and The Band retreating to that famous pink house in Woodstock, he decided he could do so as easily right there in Tennessee as anywhere else.

Appleton recruited a few other bright sparks, none of them your prototypical computer nerds. There were Scott Scheinbaum, a musician and composer who had spent the last fifteen years playing in various local rock bands and working in record stores to make ends meet; Jamie Wicks, an accomplished young visual artist, described by a friend from school as “the quiet guy who sits next to you in class and draws pictures of monsters”; Andrew Nelson, a journalist by education who had grown tired of writing puff pieces for glossy lifestyle magazines; and Eric Quist, an attorney and childhood friend of Appleton. “Bill inoculated [sic] us with his vision of becoming multimedia superstars and taking over the world,” says Scheinbaum. The five of them hatched their plans for world domination in Appleton’s basement before officially founding CyberFlix in May of 1993, with Appleton as the majority stakeholder and decider-in-chief. The division of labor on their games broke down obviously enough: Appleton would be the programmer, Scheinbaum the composer and sound-effects man, Wicks the pixel artist and 3D modeller, Nelson the designer and writer, and Quist the business guy. In fact, by this time they had their first game just about ready to go.

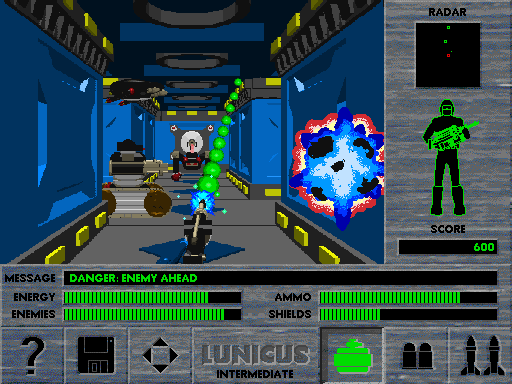

It went by the name of Lunicus. More of a tech demo than a carefully designed game, it began as a graphic adventure that took place on the titular Moonbase Lunicus, only to turn into a frantic corridor shooter, a slightly more sophisticated Castle Wolfenstein that came complete with a pounding rock-and-roll soundtrack. But everyone seemed to agree that its most impressive feature was the sheer speed with which it unspooled from the CD-ROM, thanks to some proprietary software technology developed by Appleton. Called a “mindblower” by no less a pundit than Steven Levy (author of the seminal book Hackers), the game sold 50,000 copies on the Macintosh, then was picked up by Paramount Interactive and ported to Microsoft Windows, where it did rather less well in the face of much stiffer competition. A follow-up called Jump Raven that was still faster did even better in a Mac marketplace that was starving for just this style of flashy action game, selling by some reports almost 100,000 copies.

CyberFlix was riding high, basking in the glowing press they were receiving inside the small and fairly insular milieu of Mac gaming. Being so thoroughly immersed in that world could distort the founders’ perspective. Jump Raven “was the fastest thing on the Mac,” says one early CyberFlix employee. “And that was back when the Mac was going to take over everything.”

CyberFlix moved into a snazzy loft in the center of Knoxville, Tennessee, and set about burnishing their hipster credibility by throwing parties for the downtown set, with live bands and open bars. Knoxville wasn’t quite the country-bumpkin town that East and West Coast media sometimes like to stereotype it as; its three largest employers were the University of Tennessee, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Many people in local government and business were eager to see CyberFlix as the progenitors of a new line for the city in multimedia. In a major publicity coup, Newsweek magazine was enticed to come down and write a two-page feature on the company, in which the wide-eyed reporter said that Appleton had become “something of a legend” during his time in Silicon Valley — this was something of a stretch — and called the house in whose basement the founding quintet had gotten together a literal log cabin. Others, however, were less credulous. One consultant who was hired to help the company work out a proper business plan remembers that Appleton “absolutely would not listen. He would sit and seem to listen, and then he was off to something else. It was exasperating.”

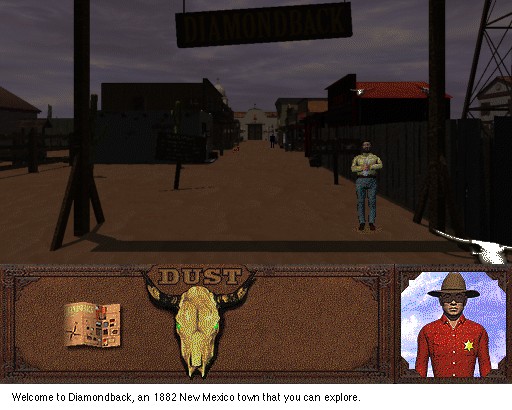

One of the things he was off to was CyberFlix’s next big game, a Western homage or send-up — the distinction is never clear, and therein lies many of the game’s problems — called Dust: A Tale of the Wired West. It was to be an unadulterated adventure game, whose action elements were limited to a few anodyne mini-games. CyberFlix used mostly employees and friends to play its characters — and therein lies another of the problems. Like many games of its technological ilk and era, Dust lacks the courage of its convictions, resulting in a fatal case of split personality. It seems that CyberFlix first intended to tell a fairly serious story. But as the amateurish acting and the limitations of their tools presented themselves, it drifted further and further into camp as a sort of defense mechanism, albeit without excising the would-be “dramatic” beats that had already been laid down. The result was, as Arinn Dembo noted in a scathing review for Computer Gaming World magazine, a comedy with dramatic relief, an approach that doesn’t work nearly as well as the opposite. Dembo’s concluding paragraphs are so well-stated, and apply so well not just to this game but to many other adventure games, that I’d like to quote them here.

The confusion in the design of this game brings up a general point, which is this: if you want to use dramatic elements in any narrative, you have to earn them. That means taking your subject seriously, even if it is “just a computer game.” Someone has to go to the trouble of fashioning characters deeper than your average mud puddle (and that includes giving them names that aren’t farcical), and writing dialog for them that sounds like something a real person might say.

If, on the other hand, your intention is to satirize the form and make fun of its tropes and limitations, you lay your cards on the table from the start; you don’t try to tap into drama that you don’t deserve. It’s either Blazing Saddles or The Unforgiven — you can’t mix the two. Computer-game writers need to learn that comedy is not a fallback position, something you do when you don’t believe you’re competent to sustain the drama. Satire and farce can be done well, and I’m not against them, but I’m against using them as a screen for poor storytelling.

All of this was made even more problematic by the way that even the jokes usually failed to land. The name of Dust, for example, was intended as a strained “ironic play” on the name of Myst. But this literally no one cottoned onto, until a peeved-sounding CyberFlix employee revealed it in an interview.

The same CyberFlix representative said that, of 90 publications that reviewed Dust, 88 of them recommended it. If so, I managed to stumble on both of the exceptions, and, unfortunately for CyberFlix, they were both biggies: the aforementioned Computer Gaming World, the journal of record among the hardcore set, and Entertainment Weekly, a major taste-maker among the mainstream-entertainment set which the company wanted desperately to reach. Released in late 1995, Dust sold only 30,000 copies between its Macintosh and Windows incarnations. In the aftermath of its failure, CyberFlix was forced to take on more plebeian contract work, such as porting software from Windows to Mac and implementing pre-written design briefs for educational products. Other folks at the company turned to simpler, less expensive sorts of original games. For many both inside and outside of Cyberflix were now beginning to wonder whether interactive movies were really destined to be the future of mainstream entertainment after all. But CyberFlix had one more big game of the old style still in them — the one that would write them into gaming history as something more than just another flash in the pan from the 1990s multimedia boom.

It must be conceded that Titanic: Adventure Out of Time did not have a very auspicious gestation. Its mastermind Andrew Nelson admits that he was prompted to make it by a logic far more plebeian than any of the grand philosophical meditations about fate and hubris that the great ship’s sinking has so often inspired. Back when CyberFlix was just getting off the ground, he’d had an interesting conversation with his sister-in-law: she “was intrigued with these new CD-ROM games, but she had heard they take forever and she didn’t have that much time.” Soon after, he read a magazine article about the Titanic, which noted that the ship had sunk two and a half hours after hitting the iceberg. That seemed like just about the right amount of time for an interactive movie that could appeal to busy adults like his sister-in-law. He decided to take the idea up with Bill Appleton and his other colleagues.

Initially, he didn’t have any more luck than Steve Meretzky had enjoyed at Infocom or Legend with his own Titanic concept. Appleton was particularly unenthusiastic. But Nelson kept hammering away at him, and finally, after Appleton’s own brainchild of Dust had proved a bust, he got his way. The company would go all-in on one last big adventure game.

The project may have been born out of practical commercial reasoning, but that didn’t keep it from taking on a more idealistic personality now. Nelson and many of those around him became full-bore Titanic fanatics. “We read all the books, listened to tapes of survivors, looked at 750 different pictures,” says Scott Scheinbaum. They laid out their virtual ship from the builder’s blueprints that had been used for the original — the very same documents, in fact, that James Cameron and friends were using to build their Titanic replica out of real steel down in Mexico at the very same time, although no one at CyberFlix was aware of this. Computer games which are labelled as “historical” tend to be strategic war games, exercises in moving abstract units around abstract fields of battle. CyberFlix was attempting a different kind of historical re-creation — a living, immersive view of history that dropped you right into the past as an individual on the scene.

In that spirit, Nelson and his colleagues set out to present as accurate a reproduction of the ship as the resources at their disposal would allow; again, they took their own endeavor as seriously as James Cameron was taking his. They tried to make every detail of every room as authentic as possible, knowing all the while that, while a movie director’s cameras had the luxury of gliding quickly over the surface of things, their players would be able to move around of their own free will in the spaces CyberFlix created and linger over what they saw to their heart’s content. This only made it that much more important to get things right.

A journalist named J.C. Herz came to visit CyberFlix in Knoxville for part of a book she was writing about videogame culture. She found an office with a “24-hour Kinko’s Copies atmosphere — full of equipment and overworked twentysomethings, simultaneously frenetic and oddly mellow.” She was especially taken by a “photo researcher” named Billy, who in his country boy’s baseball cap looked and talked like Bo Duke from The Dukes of Hazzard. “I do the carpeting for the Titanic,” he told her by way of introduction.

We have a room where you start out in the game, and I’ve outfitted the desk with postcards that you can actually flip over and read, and magazines like Brave New World, and I’ve designed the covers for ’em, so you can pick those up and look at ’em. There’s a lot of detail in there that we don’t even expect people to actually look at. It’s like, if you were just tryin’ to half-ass it and get through it, you might make a lamp, but you might not make the electric cord that goes behind the desk. We’re tryin’ to get all the detail in there. There’s a lot of games that you look at today, and a lot of people don’t take the time and energy to go in and really work with their maps to make ’em look real, so they end up coming out lookin’ plastic or fake. I made it so that when you click on [a] scrapbook, it opens up, and then all the pages are just full of imagery, you know, ephemera, things like that. So I go out and I find all the stuff to go in the scrapbook and put it in there. That’s the fun job. I could spend a day or I could spend a month on that book.

I worked 36 hours in two days last week. But they try to make it as accommodating as possible. We’ve got showers, you know. And they stock the refrigerators with Cokes. Everybody gives you Cokes. They want you gettin’ wired so you stay there all the time. And they got some couches. So, I mean, you can stay here forever.

Another of the employees she met was named Alex, a rough-looking character with a Mohawk haircut, earrings, and tattoos to complement his “lengthy criminal record,” who had recently discovered a latent talent for computer art. He demonstrated that not quite everyone working on the Titanic game shared Billy’s passion for it. Long force of habit kept him talking about the people who ran CyberFlix as The Man, even though they let him get away with just about anything.

Whatever it takes to keep us here. Whatever we want. You can come in looking like a wreck, reeking of booze, whatever, and they’re never gonna fire you for it because they need you.

Luckily enough, they’ve been thoughtful not to force any kind of real schedule on us. Just get in when you can and do your shit. So, I just go to work doing whatever I have to do, build sets and do props, little things here and there where it needs to fit in, do movies and help. While I’ve got big jobs off running on the SGI [graphics workstation], I just jump around and do little different things, 2D work or whatever. As long as it takes is as long as you’ve got to spend, and if you’re here friggin’ eighteen hours a day, so be it.

And it’s kind of very strange for me because until I came up here to do this I was always working construction, my whole life, and I felt sorry for all the poor bastards trapped in air-conditioned prisons all day, and I thought it was so much fun to be roaming around on the job site, getting sun and running and hollering and screaming. And that’s all well and good, but you ain’t never gonna make shit. You’re gonna die poor or you’re gonna die pissing away your social-security check in some stinking little bar, and that’s no good. So, I just decided to take the step and at least do this for a few years to say that I could do it, and make some money out of it. If something went horribly wrong here tomorrow and I got kicked out or fired or I had to leave, I would just throw some things in the truck, get out, and go someplace else and do it. Because this industry is just replicating itself at such a disgusting rate, and everybody’s got something to do. And sure, not everything is quality, but it doesn’t matter. It’s like, you got money? All right, pay me, I’ll do it. Give it up. And then you just do it and move on again.

Of course, a game consists of more than just its graphical presentation, regardless of whether the latter is created lovingly or for reasons of filthy lucre. What, then, was CyberFlix’s Titanic game actually all about, beyond the obvious?

Andrew Nelson named his game Titanic: Adventure Out of Time because it really does involve time travel — which, as readers of the previous article in this series will recognize, is rather an ongoing theme in ludic Titanic fictions. It opens not in 1912 in the North Atlantic but in 1942. You play a former agent in His Majesty’s Secret Service who has fallen on hard times. You’ve been drinking your life away in your dingy flat, still haunted by the mission that destroyed your promising career — an espionage mission which took place aboard the Titanic. (Shades of Graham Nelson’s Jigsaw, although the similarities would appear to be completely coincidental.) Then a German bomb falls on your head, but instead of killing you it opens up a rift in space-time, sending you back to April 14, 1912, to try again.

You arrive in your cabin aboard the Titanic at 9:30 on that fateful evening, two hours before the collision with the iceberg. After an introductory spiel from the ship’s steward, you’re free to start exploring. Indeed, the meticulously re-created ship lies at the heart of this game’s appeal. You can roam freely through First Class, Second Class, and steerage; up to the promenade decks and into the bridge and wireless room; to the ship’s gym, complete with state-of-the-art exercise equipment like the “electric camel”; to the gentlemen’s smoking lounge and the Café Parisien; to the squash court and the Turkish sauna, with its alarmingly named “electric bath”; even down into the boiler rooms and the cargo holds. All of these and more are presented as node-based spaces pre-rendered in first-person 3D — in the superficial style of Myst, in other words. But do remember the opening to this article, when I warned you not to underestimate this game. CyberFlix’s technology was better than the vast majority of Myst clones that were flooding the market at this time, and their ambitions for this project at least were higher.

There are in fact only a handful Myst-style set-piece puzzles here, none of them terribly difficult. Instead of fiddling endlessly with esoteric mechanics in a deserted environment, you spend your time here — when not just taking in the views like a virtual tourist, that is — actually talking to a diverse cast of characters whom you meet scattered all over the ship, who in the aggregate are a pretty good representation of the many nationalities, professions, and social classes that were aboard the real Titanic. Having apparently learned a lesson from Dust, CyberFlix splashed out for mostly professional actors this time. The accents are pretty good, and the voice acting in general is, if not always inspired, serviceable enough by the standard of most productions of this nature and vintage.

Prior to the Titanic‘s tragic rendezvous with the iceberg, Adventure Out of Time runs on plot rather than clock time. That’s to say that time aboard the ship, which you can keep track of via your handy pocket watch, advances in increments of anywhere from five to fifteen minutes only when you complete certain milestones. If you choose to do nothing but wander around taking in the scenery, in other words, you have literally forever in which to do so — which isn’t a bad thing, given how big a part of the game’s appeal this virtual tourism really is. In another testimony to just that reality, CyberFlix included a “tour mode” separate from the game proper, which lets you explore the ship whilst listening to historical commentary. One has to assume that, just as most of the people who bought Myst never got off the first island, most of the people who casually plucked this game off a shop shelf were content just to poke around the Titanic for a while and call it a day.

But let’s assume that you’re one of the minority who chose to go deeper. As noted above, progressing through the milestones doesn’t entail solving logic puzzles so much as it does social ones. You scurry all over the ship, from the top of the crow’s nest to the bowels of the engine rooms, talking to everyone you can find, running fetch quests and conducting third-party diplomacy. It goes without saying that a real person on the real ship could never possibly have covered this much ground in a bare two hours, but it doesn’t really matter. Thankfully, in most situations you can jump from place to place by clicking on a map of the ship given to you by the steward at the beginning of the game. You soon learn that there’s a bewildering amount of stuff going on aboard this version of the Titanic well before it hits the iceberg. British and German and Russian and Serbian spies and double agents are all aboard, intriguing their little hearts out in the name of great-power politics.There’s a jewelry-smuggling ring, a servant girl who’s blackmailing the steel kingpin who got her pregnant, even a former flame of your own begging you to help her out with this and that for old times’ sake. And then there’s a rather mediocre painting being passed around, which the epilogue will reveal is from the hand of an obscure Austrian artist named Adolf Hitler…

Finding out about everything that’s going on aboard will likely require multiple playthroughs. For every time you do something to add minutes to the clock, you run the risk of losing the chance to see things that were taking place during the time window that’s just passed. It’s occasionally possible to get all of the intricate plot machinery fouled up and end up with someone talking to you familiarly about things you know nothing about, but this is relatively unusual. Very few other adventure games have attempted to offer their players such a freewheeling story space as this one, and even fewer have succeeded this well. There are no complete dead ends here that I know of; every player’s story can eventually be brought to a resolution of some kind if she just keeps poking at things long enough.

These two hours before disaster strikes are charged with the dreadful foreknowledge of what’s coming — with the knowledge that, if the law of averages holds true, two out of every three of the people you talk to won’t live to see the dawn. I played this game last winter, when we were in the process of moving house and my wife was already working and staying in another town. Sitting all alone in an empty living room on a cold, dark Scandinavian evening, surrounded by the souvenirs of our life together packed up in moving boxes, now strikes me as the perfect environment in which to appreciate it. Others have similar memories. Andrew Nelson:

People use the word “haunting” a lot to describe this game. And I know the feeling, because late at night while I was checking out if the dialog was working and I was strolling down those hallways — and how they were lit by our designers, and the amazing score that Scott Scheinbaum did, it had a very otherworldly feeling to it. Sometimes even I would get chills walking through it and encountering some of these passengers.

It’s debatable to what extent these feelings are the product of real aesthetic intent and to what extent they’re mere artifacts of the technology used to create the game, not to mention the knowledge we possess that’s external to its world. Yet we shouldn’t be too eager to look askance at any game that manages for whatever reason to evoke feelings in its player that go beyond the primary emotional colors, as this one does. And then, too, some things plainly are done, cleverly and deliberately, to heighten the sense of encroaching doom. For example, little establishing cut scenes play from time to time, showing the ship sailing inexorably onward toward its date with a cruel destiny.

After said destiny comes to a head and the iceberg is struck, everything begins to feel more immediate and urgent, as it should. At this point, plot time goes away in favor of something close to if not quite the same as clock time: the clock ticks a handful of seconds every time you make a move as you attempt to wrap up your espionage mission and get certain vital objects safely off the ship along with your own person. One might say that this is the real stress test for the game as a fiction. Can it muster the gravitas to depict a tragedy as immense as this one in an honest, unflinching way?

Alas, the short answer is no, not really. Some of this can be blamed on technological constraints; a Myst-style engine is better suited to contemplative exploration than the mass chaos the game is now attempting to project. Yet there’s no denying that the writing also fails the test in the breach. One or two of the characters behave just about believably. The most unnervingly realistic reaction comes from a snobby old First Class busybody who has refused to get into the first lifeboat offered to her because it’s “full of people I don’t know,” and because, like so many passengers, she didn’t truly believe the ship would sink. Now she clutches her pearls alone there on the deck and begs forlornly for assurance that surely there will be more lifeboats, won’t there? But the majority of characters fall victim to the old Dust syndrome. Unable or unwilling to stare down tragedy without blinking, the game falls back on jarringly inappropriate comedy. In terms of its fiction, the actual sinking is by far the weakest part of the game; we can feel thankful that this climax takes up a fairly small portion of the full playing time. Still, it does have one practical saving grace: it gives you one last chance to wrap up any loose ends you failed to get to earlier — one last chance, as it turns out, to change history, hopefully for the better.

For in the epilogue the game returns you to 1942 and presents your actions aboard the Titanic as having determined the course of world history over the last 30 years; think of it as the ultimate riposte to Graham Nelson’s claim that the disaster was not any “turning point” in history. The history for which you’re responsible can be much the same as the timeline we know or even worse. There’s an element of black comedy to many of these scenarios, as when you avert both the First World War and the rise of Adolf Hitler (who has vanquished the monster called Envy that was lurking in the depths of his soul by becoming a successful painter selling vacantly pleasant landscapes to middle-class housewives), only to see the entire world get steamrolled by the Soviet Union. It makes me think of dodging the iceberg in Dateline Titanic: “Oh, no! You hit another one!” But in the ideal case, where you’ve chased down every single plot thread and wrapped them all up neatly, history turns out markedly better, with neither a First World War, a Second World War, nor (presumably, in that there is no Soviet Union) a Cold War.

Adventure Out of Time is an impressive piece of work in many respects, standing out not least because it’s so much more ambitious and, well, just better than CyberFlix’s track record before it would ever tempt one to suspect. It’s possible to finish it with a very different story to tell about your time aboard the Titanic than someone else who has accomplished the same feat. And that is a very rare quality in adventure games.

That said, I can’t quite say that I love this game unabashedly. Its failings in the writing department — its inability to make me really care about any of the characters aboard or to build upon the vague sense of dread it has so masterfully engendered when the time comes for sharper emotions — keep it from joining my own top rank of games. Nevertheless, its rich grounding in real history and the formal ambition it displays mark it as the labor of love it so clearly was. It remains well worth playing as an example of a path seldom taken in adventure games, a welcome example of a game that’s much, much more than it first appears to be.

Its commercial trajectory, on the other hand, is a case study in how those things sometimes don’t matter a whit. Sometimes, all you need to do to have a hit is to get the timing right.

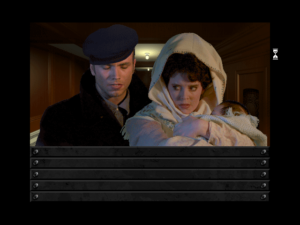

Aboard the Titanic. The eeriness of wandering the doomed ship, which is almost deserted thanks to the limitations of the technology used to re-create it, is what most players seem to remember best about the game.

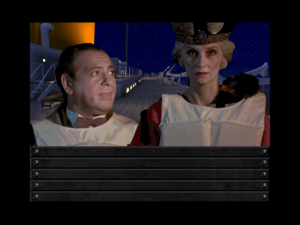

Penny Pringle, your intelligence contact aboard the ship. Stills of real people in costume were spliced over the computer-generated graphics. Their lips and facial expressions were then painstakingly hand-animated to match their dialog.

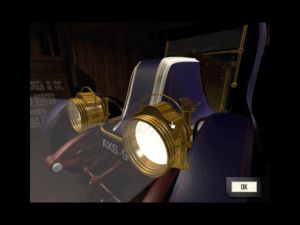

One of the relatively few mechanical puzzles involves a decoding machine. More shades of Graham Nelson’s Jigsaw, whose Enigma machine is one of text adventuring’s all-time classic puzzles.

Fans of James Cameron’s movie will recognize the Renault Type CB Coupé de Ville automobile in which Jack and Rose make love for the first and only time. It’s used for less carnal purposes here, as a handy source of illumination in a dark cargo hold. There really was such a vehicle aboard the Titanic, a car that a wealthy American coal and iron heir named William Carter had purchased and was taking home with him after a family vacation in Europe. Unlike their new car, Carter and his family survived the sinking. He filed a claim with the White Star Line and was reimbursed $5000.

Another amusing parallel with the movie is this pair of characters, named Jack and… Shailagh. (Okay, the parallel isn’t perfect.) They’re brother and sister rather than star-struck lovers, but Jack is as noble as Leonardo DiCaprio’s character, and like him sacrifices himself in the end to save the one he loves.

It all starts to go a bit sideways when the ship starts to actually sink, a tragedy which the game seems constitutionally incapable of facing, instead giving us awkward attempts at comedy.

The Titanic was already having one of its recurring moments in media when Adventure Out of Time was released in late 1996, under CyberFlix’s own imprint because the old-media mavens that had been serving as their publishers until this point were all bailing out of games in the wake of disappointing sales. One of the biggest literary novels of the year, shortlisted for the Booker Prize, was Beryl Bainbridge’s Every Man For Himself, about a young American who sails aboard the ship and interacts with many historical figures before and on the night of the disaster. The following April, a full-blown song-and-dance musical about the ship opened on Broadway, a dubious proposition on the face of it that would nonetheless run for 804 performances.

Tailwinds like these, along with the eternal recognizability of the Titanic name itself, were enough to lift Adventure Out of Time to sales of 100,000 copies in its first year on the market, despite reviews from the hardcore gaming press that were unenthusiastic at best about a product that was widely dismissed as just another tired Myst clone. “If the ocean were as shallow as Titanic‘s gameplay,” wrote Computer Gaming World in a valiant but confused attempt at clever wordplay, “the real ship would never have sunk.” But such reviews really didn’t matter at all by this point; even during this first year, the people who bought Adventure Out of Time generally weren’t the ones who read the likes of Computer Gaming World. Be that as it may, 100,000 copies sold would no doubt have been the limit of the game’s success, had not James Cameron’s movie dropped on December 19, 1997, just as Adventure Out of Time was getting decidedly long in the tooth by the standards of the novelty-obsessed games industry.

The tide had begun to turn for Cameron’s over-time, over-budget film some weeks before that date, when critics traveled to Tokyo to catch some early screenings. They came back raving about what they proclaimed to be that rarest of beasts, a showy blockbuster that could also make its audience think and feel something that went beyond the adrenal emotions. One critic stated that “Titanic plumbs personal and philosophical story depths not usually found in event-scale movies.” “It is a masterwork of big-canvas storytelling,” said another, “broad enough to entrance and entertain yet precise and delicate enough to educate and illuminate.”

The movie earned $29 million in the United States on its opening weekend, then $35 million the next weekend. Just twelve days after its debut, it was already halfway to earning back its much-mocked $200 million budget from domestic receipts alone. Four weeks after that, that milestone was already $100 million in its rear-view mirror, with Hollywood Reporter declaring that it had “shattered all previous models of film performance at the nation’s theaters.” On February 24, 1998 — just nine weeks after its release — it officially became the most successful film in history. One week later, its worldwide gross surpassed $1 billion. It was nominated for fourteen Academy Awards and won eleven of them, including those for Best Director and Best Picture.

Titanic was simply inescapable during 1998. When you turned on the radio, there it was, in the form of Celine Dion’s gloriously overwrought theme song; when you turned on the television, someone was bound to be talking about the film and/or the disaster that inspired it; when you went to work, your colleagues were discussing it around the water cooler; when you came home, you found that your teenage daughter had bought yet another poster of Leonardo DiCaprio to watch over her from her bedroom wall. Not everybody loved the film, mind you; some contrary souls dared to point out that the dialog was a bit trite and the love story more than a little contrived. But absolutely everyone had to reckon with it — not least among them its two young stars and its director, condemned to spend the rest of their careers answering as best they could the question of what you did next after you had already made the biggest movie in the history of the world.

All of this redounded to the immense benefit of some modest little CD-ROMs sitting on the shelves of software stores all over the country, due shortly to be sent back to the distributors that had sent them out. Now, thanks to the film, they suddenly started to sell again — to sell faster than they ever had before, so fast that store owners were soon clamoring for more of them from those selfsame distributors, causing a mad scramble at CyberFlix to crank up the presses once again. Adventure Out of Time enjoyed a whole new commercial life, an order of magnitude larger than its first one. Now companies were knocking at CyberFlix’s door to release the game to European and Asian markets; it was localized into seven different languages in a matter of weeks. By the end of 1998, worldwide sales had surpassed 1 million units. Well after the heyday of interactive movies and adventure games in general, it became the very last of its breed to hit that magical milestone.

But, surprisingly in an industry where one profitable game tends to beget another one just like it, CyberFlix never even tried to make anything else like Adventure Out of Time. After the game’s initial release and modest initial success, Andrew Nelson had wanted to continue to plow the same ground, with a game set aboard another glamorous and doomed means of conveyance: the airship Hindenburg. (Adventure Out of Time itself includes a hint about what was gestating in Nelson’s mind, via a Hindenburg ticket stub you can stumble across in your desk drawer in 1942.) “We’ve got this historical-fiction genre nailed,” said Nelson. “We have this new audience of people who never played a computer game.” But Bill Appleton, looking back on a 1996 which hadn’t yielded any huge adventure hits like in earlier years, wasn’t so sure. Nelson finally gave up trying to convince him and left the company in April of 1997, eight months before Cameron’s film changed everything. CyberFlix released only one major game after Adventure Out of Time, a pirate caper called Redjack: Revenge of the Brethren that returned to the model of Lunicus and Jump Raven, combining multimedia-heavy adventure-style gameplay with 3D action. It sank without a trace even as Adventure Out of Time was soaring to new heights; by some accounts, it sold as few as 10,000 copies in all.

That was enough to convince Bill Appleton, an unsentimental realist about the games market, that his company simply wasn’t made for these times. He was able to face what most others in his position would have closed their eyes to: that the success of Adventure Out of Time was sui generis, a fluke driven by a fortuitous happenstance, a stroke of blind luck that would never, ever come again, no matter how great an adventure game they made next time out. For it did nothing to change the fact that the multimedia boom, which had always been more wishful thinking than reality, was over, and the styles of game it had favored were in precipitous decline. So, he set about dismantling his company even as millions were still pouring into it from Adventure Out of Time. Better to pocket that money and go out a winner than to piss a fortune away on some grandiose new production that was as doomed to fail as the Titanic had been doomed to strike that iceberg. It was a brutal decision, but, from a pure business standpoint at least, it’s hard to argue that it was the wrong one.

Still, there are lingering questions about the way Appleton went about it, especially the bonuses of close to $2 million which he awarded to himself over the course of 1998 even as he was busily shedding staff. On November 30 of that year, he announced to the last of his employees that CyberFlix was done as anything but a holding company to collect the last of the revenues from Adventure Out of Time. Then he decamped for Silicon Valley to “build enterprise software for small companies,” never even saying goodbye to the four other dreamers who had once gathered in his cellar. Of them, only visual artist Jamie Wicks stayed in the games industry, going on to work on the hugely popular EA Sports lineup.

Neither Billy nor Alex, those two unlikely game developers interviewed by J.C. Herz when they were making Adventure Out of Time, ever worked in the industry again either. Likewise, Knoxville’s dream of becoming a new locus of artsy high tech died with CyberFlix. A 1999 history of the company’s rise and fall, written by one Jack Neely for the alternative urban newspaper Metro Pulse, describes the old offices standing “empty and silent,” bringing to mind those haunted corridors of the Titanic in Adventure Out of Time.

“This weekend I was in a mall in Atlanta,” said one former CyberFlix employee whom Neely interviewed for his article, “going through [a] store, and they had a copy of [Adventure Out of Time] on the cheap rack. It’s still around. But it’s kind of sad to see it there.” Already by then, the best game by far to come out of Cyberflix had met the inevitable fate of all Titanic productions, just another unmoored piece of ephemera in the ever-growing debris field of pop culture that surrounds the most famous sunken ship in the world.

(Sources: the books Titanic and the Making of James Cameron by Paula Parisi and Joystick Nation by J.C. Herz; InfoWorld of September 14 1987; Compute! of March 1989; Computer Play of April 1989; MacWorld of May 1989, June 1989, April 1992, June 1992, January 1994, and February 1995; Computer Gaming World of August 1993, April 1994, December 1995, and March 1997; MacUser of October 1993 and January 1996; Next Generation of November 1996; Knoxville News Sentinel of November 20 2006; Dragon of February 1987; JOM volume 50 number 1; Knoxville Metro Pulse 942; Newsweek of August 28 1994; Entertainment Weekly of September 22 1995. Online source include an Adventure Out of Time retrospective at PC Gamer, a Game Developer interview with Andrew Nelson, and Stay Forever‘s interview with Andrew Nelson.

Titanic: Adventure Out of Time is available for digital purchase at GOG.com.)