Anita Sinclair’s original vision for her company Magnetic Scrolls cast it as Britain’s answer to Infocom, pumping out multiple finely crafted traditional text adventures each year — albeit text adventures with the commercially critical addition of attractive illustrations. As 1988 began, Magnetic Scrolls had barely begun to execute on that vision, having released just three games. But the times were changing and the text-adventure market clearly softening, and those realities were already beginning to interfere with her plans. Already by the beginning of the year, Magnetic Scrolls was underway with by far their most ambitious project to date, a radical overhauling of the traditional old parser-driven text adventure that was to gild the plain-text lily with not just pictures but clickable hot spots on said pictures, sound and music, animation, clickable iconic representations of the game’s map and the player’s inventory, a clickable compass rose, a menu of verbs, and much, much more, all tied together with an in-house-written system of windows and menus — “Magnetic Windows” — borrowing heavily from the Macintosh. Lurking almost forgotten below all the bells and whistles would be a game called Wonderland, an adaptation of Lewis Carroll.

We’ll get to Wonderland, released at last only in 1990, in due course. Today, though, I’d like to look at the twin swan songs of Anita Sinclair’s earlier vision for Magnetic Scrolls, both of which were already in the pipeline at the time the Wonderland project was begun and both of which were released in 1988.

Corruption, the first of the pair, was the brainchild and personal pet project of Rob Steggles, designer in the broad strokes of Magnetic Scrolls’s earlier The Pawn and Guild of Thieves. Having worked with Magnetic Scrolls strictly on an occasional, ad-hoc basis heretofore, Steggles finished university after the spring semester of 1987 and called Anita Sinclair to ask for a job reference. Instead, she asked if he’d like to come work for Magnetic Scrolls full-time. Once arrived, Steggles convinced her to let him pursue a project very different from anything Magnetic Scrolls had done to date: a realistic, topical thriller set in the present day and inspired by Infocom’s early trilogy of mysteries. She agreed, and Hugh Steers, another of Magnetic Scrolls’s founders, came to work with Steggles as programmer on the project. Largely the creative vision of Steggles alone, Corruption represents a departure from the norm at Magnetic Scrolls, whose games, much more so than those of Infocom, tended to be collaborative efforts rather than works easily attributable to a single author.

Whether accidentally or on purpose, Steggles captured the zeitgeist in a bottle. This being the height of Margaret Thatcher’s remade and remodeled, hyper-capitalistic Britain, he chose to set his thriller amid the sharks of high finance inside The City of London. He had enough access to that world to give his game a certain lived-in verisimilitude, thanks to friends who worked in banks and a father who went to work every day in the heart of the financial district as an executive for British Telecom. Steggles nosed around inside buildings, chatted with traders, and pored over the Insider Trading Act to get the details right.

In December of 1987, the film Wall Street, with the immortal Gordon Gecko of “greed is good!” fame, debuted in the United States. It appeared in Britain five months later, corresponding almost exactly with the release of Corruption. Magnetic Scrolls couldn’t have planned it better if they’d tried. Today, Corruption is one of the relatively few computer games to viscerally evoke the time and place of its creation — a time and place of BMWs and Porsches, lunchtime deal-brokering at the latest trendy restaurant, synth-pop on the CD player, cocaine bumps in stolen bathroom moments.

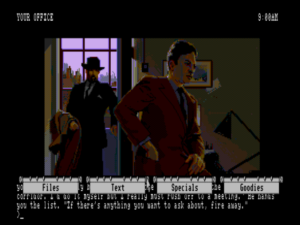

In Corruption, you play a young City up-and-comer named Derek Rogers. You’ve just been promoted to partner in your firm for — you believe — your hard work in landing an important deal. In the course of the game, however, you learn that the whole thing is an elaborate conspiracy to frame you for the illegal insider trading for which another partner and his cronies are being investigated. The ranks of the conspirators include not only the head of the firm and many of his associates but even your own wife, who happens to be having an affair with the aforementioned head. Revolving as it does around betrayal and adultery, with drugs thrown in to boot, Corruption is certainly the most “adult” game Magnetic Scrolls would ever make. Steggles says that it was written in a conscious attempt to address an “older” audience — a bit of a reach for him, given that he himself was barely into his twenties.

Corruption acquits itself pretty well in some ways, remarkably so really given its author’s youth and inexperience. The atmosphere of cutthroat high finance comes across more often than not, and the grand conspiracy arrayed against you, improbable though it may be, is no more improbable than those found in a thousand Hollywood productions, among them Wall Street. A crucial feelie is a conversation on an included cassette, professionally produced by Magnetic Scrolls’s resident music specialist John Molloy and scripted by Michael Bywater, still a regular presence around the offices. Like much in Corruption, it’s very well done.

Drawn by Alan Hunnisett and Richard Selby rather than Geoff Quilley, Corruption‘s pictures look a little dark and drab in comparison to Magnetic Scrolls’s fantasy games — but maybe that’s the right choice for this milieu.

Unfortunately, as a piece of game design Corruption falls down badly. Unsurprisingly given that it was inspired by the Infocom mysteries, Corruption is a try-and-try-again game, the process of solving it a process of mapping out the movements of the characters around you and learning through trial and error where to be when and what to do there to avoid their traps and crack the case. But it just doesn’t work all that well even on those polarizing terms. The Infocom mysteries, for all that they rely heavily on what would be attributed to coincidence and luck in a conventional detective novel, do hang together as coherent fictions once the winning path through the story is discovered. Corruption doesn’t. Whereas the Infocom mysteries all cast you as a detective charged with investigating a crime that has already taken place, in Corruption you start as just a happy bloke who’s gotten a big promotion. On the basis of no evidence whatsoever, you have to start following your associates around, stealing keys and breaking into their offices and cars, laying traps for your dearly beloved wife, all of which does rather raise the question of who’s the real sociopath here. Some of the actions required to win the game simply make no sense whatsoever, not even in the context of you being the most suspicious, paranoid, and devious person in an office full of them. At a certain point, for instance, you get hit by a car and wind up in the hospital. A later puzzle — a puzzle your character couldn’t possibly anticipate — demands that you have something you can only find by stealing it off a doctor in the hospital. So, in addition to being a suspicious and devious jerk with a death wish, old Derek Rogers needs to also be a hopeless kleptomaniac. Or is he just a paranoid schizophrenic? I don’t know; you can diagnose him for yourself.

Corruption is one of those games that I wonder how anyone ever solves without benefit of hints or walkthroughs. In addition to all the problems of timing, some of the individual puzzles are really, really bad. The hospital sequence in particular is a notorious showstopper, its purpose for being in the game as tough to divine as the right way to come out of it. Conversations are a more constant pain; you never know when you’re supposed to tell someone about something, nor, given the parser’s limitations, quite how to say it.

In an interview, Steggles made a statement I continue to find flabbergasting every time I read it. Speaking of Corruption‘s try-and-try-again mode of play, he said, “Believe it or not, it wasn’t a deliberate choice to do it that way and I think that if someone had made that comment about it during development we’d have stopped it because it wasn’t really ‘fair’ on the player.” But really, how could he not know what sort of game he was creating, given that he was inspired by the Infocom mysteries that offered exactly this approach to play? Still, let’s take his words at face value. Not initially realizing what sort of game he was creating — and how hard that game would inevitably turn out to be — speaks to an inexperienced designer whose ideas outran his critical thinking; we can forgive that as a venial sin. But for Magnetic Scrolls not to have arranged for him to have the feedback he needed to know of his game’s failings and correct them… that sin is mortal. It speaks to yet another adventure game released without anyone having ever really tried to play it.

There are signs that some at Magnetic Scrolls knew Corruption wasn’t quite up to snuff. Anita Sinclair came very close to actively discouraging Magnetic Scrolls’s fans from buying the game: “It doesn’t follow that if you enjoyed Jinxter, or even Guild [of Thieves], you will enjoy Corruption.” Corruption, she said, would likely have “limited appeal.”

She would be able to muster much more enthusiasm for Magnetic Scrolls’s second game of 1988. And for good reason: it’s a gem, my personal favorite in their catalog.

The game in question is called Fish!, and is the product of an unlikely collaboration involving a musician, a journalist, and a civil servant: John Molloy, Phil South, and Pete Kemp respectively. One day on a long bus ride, good friends Molloy and South were riffing on some of the absurdly difficult and unfair adventure games that were so typical of those days. The discussion proceeded to encompass satirical ideas about possible new scenarios for same. “What if you started the game as a goldfish and you had to save the world?” asked one of them at some point (neither can quite remember which). Thus was born Fish!.

Molloy, who had been doing music for Magnetic Scrolls for a couple of years by then and in addition to being a working musician wasn’t a bad programmer, was attracted to the idea of seeing how the other half lived, of designing and helping to implement a complete game of his own. As Phil South succinctly describes it, “He pitched it to Magnetic Scrolls, they went nuts.” Kemp, another good mate of Molloy’s, joined after the latter gave him a pitch he also couldn’t refuse: “A bit of fun, a bit of money, and everlasting obscurity.”

South and Kemp were soon introduced to the intimidating cast of eccentrics that was Magnetic Scrolls. South:

I remember Magnetic Scrolls being in a rather grimy and unsavoury Victorian suburb of South London and having to brave the trains late at night to get there. I remember Anita being small but scary, and possessing a wisdom far beyond her years. She terrifies the crap out of men twice her size just by looking at them. I remember Ken [Gordon] being the most laid back Scotsman I’d ever met, which puts him on track for being one of the most laid-back guys worldwide. Rob Steggles has an evil sense of humour and at the time had a real passion for Games Workshop’s BLOODBOWL board game. Michael Bywater is scary smart, hugely funny, and also possibly one of THE most grumpy men I’ve ever met.

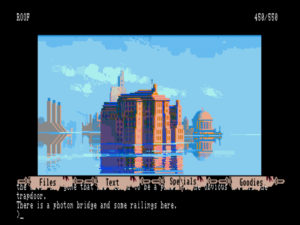

Fish! casts you as an “inter-dimensional espionage operative” who warps Quantum Leap-style among times, bodies, locations, and dimensions on the trail of criminals. At the beginning of the game, you’re enjoying a spot of rest and relaxation as a goldfish in your own private aquarium, when you’re notified that a gang of anarchists who call themselves the Seven Deadly Fins have stolen something called a focus wheel, needed to keep a planet of fish called Aquaria hydrated. First you need to assemble the pieces of the focus wheel, which the Fins have scattered across three different worlds. Then you can warp to the city of Hydropolis, capital of Aquaria, to set it into operation before the last of the water evaporates and everyone drowns.

I find Fish!‘s more colorful, surrealistic pictures to be much more attractive than those of Corruption.

As you’ve probably gathered, Fish! isn’t a very serious game. It’s rather a surrealistic riot of fishy puns and absurdist humor in the style of Douglas Adams. The prospect of neither surrealism nor Douglas Adams-style humor excites me all that much when starting a new game because those things are usually (over)done so badly, but Fish! pulls it off with aplomb. The fishy wordplay comes fast and furious, inducing groans and smiles in equal measure: “the archway is a magnificent example of craftfishship”; “any old eel could slip in here and break into every apartment on the block”; “some dolphins rush in where angelfish fear to tread”; “the police station is fished day and night by a stalwart dogfish who is ready to solve the troutiest of crimes”; “Tuna Day’s Music Ship is cluttered with amateur musicians, most of whom are playing versions of the ancient heavy-metal hit ‘Smoke Underwater'”; “glancing toward the toilet, you see a trout emerge, adjusting his flies.”

Thanks doubtless to Molloy’s background, much of Fish! is informed by music and the life of a musician. In addition to “Smoke Underwater,” he makes time to acknowledge that timeless classic “Sole Man” by Salmon Dave, and to make fun of buskers.

You notice several students loitering with intent. One of them produces a guitar and starts singing: "Come on feel my nose. The girls grab my clothes. Go why, why why any more." Oh no, he's started busking! Luckily, the other students attack and carry him off before you hear too much.

I love one early puzzle involving a Svengali music producer and his cowed assistant Rod. I know it’s anachronistic, but somehow I always picture Simon Cowell in this scene. (Spoiler Warning!)

An important-looking beetroot-faced producer enters the room behind you. "You," he shouts charmingly, "make some coffee or you're fired." He strides out.

>rod, make coffee

"Sure thing," says Rod, rushing down the corridor. You hear the kitchen door slam, then a few seconds later it slams again as Rod comes out. "That's the way to do it," he beams as he returns, holding a steaming mug of coffee.

The producer appears and grabs the mug. He looks at you and smiles a sickly smile as Rod leaves. "Well done," he says, taking a slurp, "you'll go far in this business. You've already learned the golden rule: if in doubt, delegate." Then he stomps out, looking pleased with himself.

In marked contrast to the confused and confusing Corruption, Fish! is quite fair, at least according to its own old-school lights. The three early acts, each involving the collection of one piece of the focus wheel, are all fairly easily manageable. The final act in Hydropolis, the real meat of the game, is much more challenging, another exercise in good planning and careful timing given that you have only one day to complete a very complicated mission. So, yes, it’s another try-and-try-again scenario, and far from a trivial one; I found one puzzle in particular, another entry in the grand text-adventure tradition of mazes that aren’t quite mazes, to be so complicated that I ended up writing a program to solve it for me. But the clues you need are always there, and there’s never a need to do anything completely inexplicable like stealing vital medical equipment. Good planning and careful note-taking — and maybe a handmade Python script — will see you through. I love games like this one that challenge me for the right reasons.

Whether because Anita Sinclair was much more personally enthusiastic about this project or because it was a true collaboration from the start, the authors of Fish! got the feedback that Steggles apparently lacked in writing Corruption. Phil South:

Sometimes during play testing it came out that the puzzle was too hard or to too easy. We adjusted the hardness by leaving clues. Sometimes the puzzle was taken out altogether. We played other people’s games and saw how they solved the hardness problem.

After Corruption was finished, Steggles joined the team to do some final polishing and editing, a role he describes as “basically acting as a sub-editor to bring the writing into the house style.”

Released in time for Christmas 1988, Fish! fell victim to a breakdown in the relationship between Magnetic Scrolls and their publisher Rainbird; it never enjoyed the distribution or promotion of Magnetic Scrolls’s earlier games, even as Anita Sinclair said that it stood alongside Guild of Thieves as her personal favorites in the catalog. (As a glance at my own Hall of Fame will attest, that’s an assessment with which I very much agree.) We’ll get into the breakdown with Rainbird and what it meant for Magnetic Scrolls in a future article. For now, though, suffice to say that the release of Fish! marked the end of Magnetic Scrolls’s era of greatest popularity and influence. Molloy, South, and Kemp all moved on with their lives and day jobs, leaving their days as text-adventure authors behind as a fond anecdote for their scrapbooks; none would ever work in the games industry again. Steggles departed in December after a “storming row” with Anita Sinclair over his salary and his general unhappiness with the direction of the company; he also moved on with life outside of games. Michael Bywater’s business relationship with Magnetic Scrolls ended in correspondence with the end of his romantic relationship with Anita.

In a fast-changing market, with so many of the old gang suddenly leaving, Magnetic Scrolls’s future depended more than ever on Wonderland. That project… but I said we’d save that for another day, didn’t I? In the meantime, go play Fish!. Really, how can you not love a game that describes another featureless dead end as, “This is as far as the corridor goes. On the first date anyway.”

(Sources: Games Machine of August 1988, November 1988; Computer and Video Games of July 1988; Commodore User of June 1988; The One of July 1990; ST News of Summer 1989. Online sources include “Magnetic Scrolls Memories” by Rob Steggles on The Magnetic Scrolls Memorial and an interview with Steggles at L’avventura è l’avventura. And huge, huge thanks to Stefan Meier of The Magnetic Scrolls Memorial for digging up a dump of Peter Verdi’s apparently defunct Magnetic Scrolls Chronicles website, including original interviews with Rob Steggles, Michael Bywater, Phil South, and Pete Kemp. You’re a lifesaver, Stefan!

Corruption, Fish!, and all of the other Magnetic Scrolls games are available from Stefan’s site in forms suitable for playing with the Magnetic interpreter — or you can now play them online, directly in your browser, if you like.)