By 1990, life for the programmers and artists who made adventure games for Sierra On-Line had settled down into a predictable pattern. Even-numbered years were King’s Quest years, when the company pulled out all the stops to deliver a new iteration of their flagship series that incorporated all the latest technologies — that looked and sounded better than anything they had ever done before. Odd-numbered years offered a chance to decompress, letting the creative teams apply the techniques that had been developed for King’s Quest to other games — games that were often more eclectic and, to this writer’s mind at least, more interesting — while the marketing people had more time to devise promotional strategies for same. Not coincidentally, Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards and Hero’s Quest: So You Want to Be a Hero, Sierra’s two most successful non-King’s Quest series debuts to date, had each been launched in an odd year. Sierra was making enough games by the dawn of the 1990s that even a King’s Quest year would see the release of plenty of other, non-King’s Quest games. But everyone knew where management’s priorities lay when it came time for Roberta Williams to start to think about King Graham and Daventry once again.

Thus there was never any doubt that King’s Quest V would dominate the agenda for 1990, just as there wasn’t that Ken and Roberta Williams would demand that it be an audiovisual showstopper. The Williamses and their fellow travelers were feeling their oats a bit, and by no means entirely without reason. Following the near-implosion of 1983 and 1984, Sierra had been steadily profitable for half a decade, their gross revenues growing throughout that time at a steady year-by-year clip. Unlike so many other computer-game makers, they hadn’t been damaged very much at all by the arrival of Nintendo and the resurgence of the once dead-and-buried console market; the existence of those events, so cataclysmic for so many of their peers, could never even have been guessed at from a glance at Sierra’s bottom line. While heretofore strident console haters like Trip Hawkins of Electronic Arts swallowed their pride and begged Nintendo for a license, Ken Williams stuck to his guns. Sierra published, as their press releases and annual reports never failed to proclaim, “premium-priced entertainment-software products for the high end of the consumer market” — i.e., for home computers. They hadn’t suffered the identity crisis of their peers, and their strong sense of exactly what kind of products they ought to be making was continuing to pay off.

Which isn’t to say that their business wasn’t evolving in other ways. As Sierra accelerated into a decade which they and many others believed would be marked by a merging of the interactive entertainments coming out of Northern California with the non-interactive entertainments coming out of Southern California, they took on more and more of a studio mentality, in which the programmers who wrote the code for the games would just be one part of a creative whole, no more important — indeed, quite possibly less important — than the artists who illustrated them or the composers who scored them. And nowhere was this new philosophy of game production more in evidence than in the hiring of Bill Davis as “creative director” in July of 1989.

Davis came to Sierra with no experience at all in interactive media, but with a long resume as a television director and animator that included clients like McDonald’s, Burger King, Toyota, NBC, The Children’s Television Workshop, and MacMillan and Co. His work had appeared on Sesame Street, The Electric Company, and The Tonight Show, and a short film he had made on his own time had recently been shown at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival. He was brought in explicitly to “Hollywoodize” Sierra — even if a good part of what that term encompassed in Ken Williams’s view might simply have been seen as smart, effective project management by someone else. Davis:

At Sierra, projects are getting so large, and we are getting so many projects, [that] we are concerned about losing quality. We are going to take some of the techniques that have been used in the film industry to manage gigantic feature projects and apply them here. I think we’ll gain in efficiency along the way also. It will enable many more people to work on a project, finish that project quickly, and not lose quality.

With a storyboard you are able to visualize an entire project at the beginning and locate the pitfalls, the problem areas, ahead of time, before anyone sits down at a computer to work on anything. We won’t have to trash large sections of a game that have been developed because they don’t work with another part of the game. We should be able to prevent those types of things from happening.

The conceptual core of Davis’s approach — and the one that smacked most of Hollywood — was indeed storyboarding, a technique which traditional animators had been using since time immemorial. According to an article published in Sierra’s magazine, “a storyboard might be likened to a comic strip of the whole game on paper, laid out on a large bulletin board. The game designer, the art designer, the lead programmer, and the music director meet in front of the storyboard to familiarize all concerned with all facets of the project. It is here that any problems — technical or otherwise — are brought up and worked out between these four.”

The obvious disadvantage in relying so heavily on this technique drawn from a linear form of media in a game-development context is the simple reality that games are not a linear form of media. Setting aside claimed gains in efficiency which I have no reason to doubt, I fancy I can spot some unforeseen ramifications of the approach in some of the games which would be created using it, with their tendencies to trap the player in unwinnable states if she approaches things in the “wrong” order. Bob Bates of Legend Entertainment once said to me that Sierra games seemed to him to be global “state machines,” as opposed to the more granularly simulated, object-focused games of Infocom and Legend. While this comparison doesn’t hold up on a technical level — the object-oriented language Sierra used to program their SCI engine is actually remarkably similar in conception to Infocom’s ZIL — I believe there’s something to be said for it on a philosophical level.

Nevertheless, Sierra had made their bed with Davis’s storyboard-driven methodology. The veteran game developers working there, who had previously enjoyed virtual free rein to make games using whatever methodology they wished, were now expected to lie in it. With less or more grumbling, they all did so.

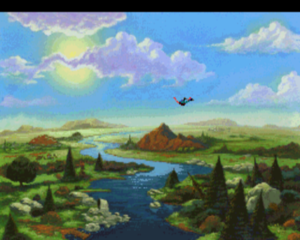

The changes Davis had been hired to implement began to affect the developers immediately after his arrival, but the new process wouldn’t be tested out in its entirety until work began on King’s Quest V some months later. In addition to the new development process, that game would, as per usual for a King’s Quest, mark the beginning of a new technological generation of Sierra adventure games. King’s Quest IV back in 1988 had heralded the arrival of the new, more flexible SCI game engine, along with full orchestral soundtracks for those with the hardware to hear them. Those changes may have seemed big at the time, but they were as nothing compared to Sierra’s latest plans. King’s Quest V would replace its predecessor’s 16-color EGA graphics with 256-color VGA graphics, and would replace its text parser with an entirely mouse-driven point-and-click interface. True to their leader’s analog roots, Davis’s artists were now expected to paint all of the scenes for the game by hand on paper; their work was then digitized, giving the Sierra games of this era a distinctive painterly quality that remains lovely to look at. Whatever else you can say about it, King’s Quest V represented the most dramatic single visual leap forward which Sierra’s games ever had or ever would make — comparable to the leap which King’s Quest IV had made two years before in terms of audio.

In design terms, however, King’s Quest V was just the latest in a long string of lowlights. If anything, it was even worse than the series’s dubious norm. Whether because of Bill Davis’s rigid storyboarding methodology or because of Roberta Williams’s endemic carelessness as a designer, or perhaps both, it’s often described as the absolute nadir of the series in terms of dead ends and nonsensical puzzles. The cognitive dissonance that existed between the series’s designs and the way the games were marketed continued to be as perplexing as it was hilarious. As always, the latest King’s Quest was positioned with one leg in what we might call the pure gaming space, the other in the edutainment space. “Come into the world of King’s Quest V… and bring the family!” trumpeted Sierra’s advertising to accompany appropriately wholesome, family-friendly art. Perhaps the lesson it was meant to impart to the little ones — at least to those of them with serious aspirations of solving it — was that it’s a cruel old world out there, appearances can be deceptive, and you can never trust anyone — least of all an adventure game with Roberta Williams’s name on the box.

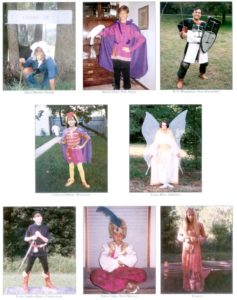

Adorable young King’s Quest fans (and one or two confused adults) dress up for a Sierra photo contest. Too bad the game secretly wants to lead them down some blind alley and never let them out again…

But none of that ultimately mattered to Sierra’s bottom line. Justifiably heralded as the beginning of a new era of Sierra adventure gaming upon its release just in time for the Christmas of 1990, King’s Quest V was sold and bought on the basis of its “vivid game scenes, lifelike animation, and breathtaking soundtrack.” Children continued to love the series for all these reasons, while parents continued to see it as a safe choice in a perilous gaming landscape. King’s Quest, in short, had long since become one of the handful of gaming brands that even those who didn’t play games at all might recognize. The Software Publishers Association honored it as the best adventure of 1990, and even Computer Gaming World, normally the most skeptical of the magazines, elected to contradict their lukewarm initial review, get with the program, and make it their adventure of the year as well. Sierra claimed that out of the gate King’s Quest V became the fastest-selling single computer game in the history of the industry. In its first three months on the market, it sold 160,000 copies; in its first fifteen months, more than 300,000 copies. And, even more encouragingly in terms of Sierra’s future prospects, the rapturous reception accorded to the potent combination of 256-color graphics with a point-and-click interface wasn’t confined to their most iconic series. Space Quest IV, the second game developed under the new methodology and technology, marketed more to the teen demographic than the tweens of King’s Quest, hit 100,000 units before its own first ninety days were up.

And there was yet more technological progress in the offing. Huge leap forward though they were, VGA and point-and-click only comprised two-thirds of the major advances Sierra was unveiling for those King’s Quest V buyers who had the right hardware. CD-ROM had been lurking out there for years now, offering almost inconceivable amounts of storage, a prospect which inspired both excitement and fear among computer-game developers and publishers; after all, what could you actually do with 650 MB worth of space? Sierra stormed into the 1990s determined to answer that question. The imagined multimedia future into which CD-ROM would lead the world had had much to do with their hiring of Bill Davis, a man who presumably knew how to make all the rich multimedia content that would be needed to fill all those megabytes.

Roberta Williams takes one of her star turns on the title screen to the CD-ROM version of Mixed-Up Mother Goose.

For their first foray into CD-ROM, Sierra chose Mixed-Up Mother Goose, a charming little educational game of scrambled nursery rhymes which Roberta Williams had first put together in the non-King’s Quest year of 1987. Sierra admitted frankly to choosing it for their first CD-ROM experiment because it was “a relatively small game,” “less expansive than a King’s Quest or Space Quest adventure.” But, having made that concession to practicality, they made few others. In addition to the expected redoing of all the graphics and the conversion to a point-and-click interface, professional actors were hired to voice every line of dialog. Intended as a showpiece and a proof of concept as much as a commercial product, Mixed-Up Mother Goose delivered in fine fashion on the former counts at least. At an industry conference, no less a personage than Bill Gates used it as the grand finale of his presentation on multimedia computing, calling it the “most compelling use of multimedia to date.” Sony chose to make it a pack-in product with their CD-ROM drives.

As befitted its series’s flagship status, King’s Quest V too had been earmarked for CD-ROM from the beginning. There were some early hopes of producing the CD release in tandem with the diskette-based release, but those fell by the wayside in the rush to get the latter done in time for Christmas. King’s Quest V instead shipped on CD in August of 1991, the first of Sierra’s full-fledged adventure games to do so. It featured the talents — admittedly, sometimes the somewhat dubious talents — of more than fifty voice actors. Ken Williams himself coined the term which the industry at large would soon be using to describe such CD-based re-releases of older games: “talkies,” a reference harking back to the period when silent films were being replaced by films with sound. Williams and many others believed that the changes the talkies would bring to the games industry would be every bit as disruptive as those they had brought to cinema all those years ago.

Indeed, Sierra felt that CD-ROM placed them on the cusp of nothing less than a technological and aesthetic media revolution. The company’s history to date had been marked by a slow move away from text: the illustrated text adventures of their earliest days had given way to the animated adventure games that were born with the first King’s Quest, and now the text parsers in those games had given way to a point-and-click interface. CD-ROM would mark the final step in that journey, offering up an immersive multimedia environment built entirely from pictures and animations, from sound and music. Sierra’s Oakhurst, California, campus already included a video-capture studio and a sound studio, and the company was investing heavily in custom hardware and software for merging the analog real world into the digital world of their games. Multimedia wasn’t just a buzzword for Sierra; it was the necessary future of their business.

Taping a scene for Police Quest 3 at Sierra’s in-house video-production facility.

But, as so many others had been doing for so long now, Sierra chafed at the excruciatingly slow progress of CD-ROM, the key to this future, into the homes of their customers. The fact was that building a CD-ROM-capable gaming computer was as expensive as it was confusing. Still, Sierra felt that their own recent history provided grounds for optimism: in the face of expense and confusion, they had succeeded in driving their customers toward sound cards at the tail end of the previous decade, so much so that by 1991 Sound Blaster and Ad Lib cards and their equivalents had found a home in most MS-DOS gamers’ computers. Sierra had accomplished this feat via a two-pronged strategy that addressed the issue from both the supply and demand side of the equation. On the supply side, they had published games — beginning, naturally, with a King’s Quest — which made spectacular use of sound, to such an extent that anyone without a sound card had to feel like she was missing out on a big chunk of the experience. And on the demand side, they had tried to ease their customers’ confusion by endorsing certain sound cards and even selling them directly at discount prices through their magazine.

Now, Sierra tried a similar strategy for CD-ROM. In the fall of 1991, they began selling a “multimedia upgrade kit” directly to their loyal customers for $795. It included a CD-ROM drive, a CD-friendly sound card, a copy of Microsoft Windows with the “multimedia extensions” included, and a selection of CD-based software published by Sierra and others. Yet Sierra’s CD-ROM push wouldn’t prove as immediately fruitful as had their sound-card push; at almost $800, one of these multimedia kits was a much harder sell than a $200 sound card. CD-ROM wouldn’t finally break out on a wide scale among computer owners until 1993, fully eight years after it had first been heralded as the next big revolution in computing. In the meantime, the vast majority of Sierra’s games would continue to ship on floppy disks; with the economics of the situation being what they were, only the more high-profile titles even saw a CD-based release.

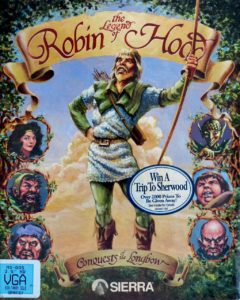

While CD-ROM thus continued to wait in the wings where it had already stood for so long, the technological innovations of the disk-based King’s Quest V were more than impressive enough for most gamers. As was typical of a non-King’s Quest year, most of Sierra’s other established series — including Space Quest, Police Quest, and Leisure Suit Larry — got a new iteration in 1991. But the most interesting Sierra adventure game of the year was a one-off called Conquests of the Longbow: The Legend of Robin Hood.

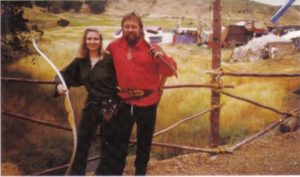

Christy Marx, the creator of that game, had a resume which seemed perfectly attuned to the new philosophy of game development which Bill Davis had inculcated at Sierra. Like Davis, she had a background in traditional cartoons and animation, having worked through most of the 1980s as a writer on the Saturday-morning-television beat: penning episodes of G.I. Joe, Dino Riders, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and even creating her own cartoon series, Jem and the Holograms, which ran for 65 episodes between 1985 and 1988. In the midst of it all, she had also found time to create her own limited-run comic-book series, Sisterhood of Steel.

Conquests of the Longbow was actually the second game which Marx wrote and designed for Sierra. It followed the Arthurian Conquests of Camelot: The Search for the Grail, released as one of Sierra’s last parser-based games in 1990. (The pair together must vie with The Colonel’s Bequest for most tortured use ever of Sierra’s “Quest” trademark.) Conquests of Camelot is unusually earnest for a vintage Sierra adventure, rich in setting and character, but it’s clear that Marx struggled to master the interactive dimension of her new medium. Certainly the game resoundingly fails to put its best foot forward. The first area most players will visit after leaving Arthur’s castle hits you first with two of the all-time worst examples of the hideous action sequences, disliked by virtually everyone, which Sierra was always shoehorning into their adventure games, then follows them up with a long string of riddles. As you might expect after a beginning like that, it doesn’t take much longer for a maze to rear its ugly head, thus completing the adventure-game trifecta of lazy design.

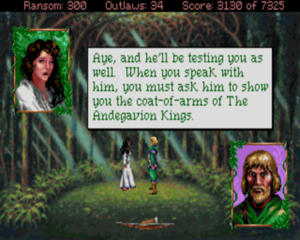

Conquests of the Longbow draws from a slightly later period in the mythical history of England than does Conquests of Camelot, taking place during the time of King Richard the Lionheart’s captivity in Austria (an era and a story which will ring familiar to anyone who has played Cinemaware’s Defender of the Crown). It’s by no means immune to the problems typical of Sierra adventure games of its vintage: its version of Sherwood Forest is pointlessly large and empty; the linear plot — surely exhaustively storyboarded beforehand — leaves you flailing about for triggers to advance the timeline; at least one or two of the puzzles are far too obscure for their own good. Yet by way of compensation it offers an embarrassment of other riches, including an authentic Medieval board game that’s very engaging in its own right and a real chance to sculpt the Robin Hood you envision — whether you prefer to make him a short-tempered killer or clever trickster or something else entirely. There are even multiple endings, based on the decisions you made throughout the game, that feel organic rather than contrived.

Even more so than that of any of Sierra’s established series, Marx’s sensibility benefits hugely from the step up to VGA graphics. Her writing, so much subtler than the Sierra norm, combines with the fine work of Sierra’s talented art team and some lovely music to create an experience that drips with the atmosphere of Merry Olde England. Marx had, she said, “adored” Robin Hood since she was a small girl, and that passion comes through almost strong enough to make even a design curmudgeon like me forgive her her sins. At any rate, Conquests of the Longbow certainly strikes this reviewer as more engaging than yet more madcap antics of Roger Wilco or Larry Laffer.

And in commercial terms as well, Christy Marx’s second game was surprisingly successful even in the face of such competition. The issue of Sierra’s official magazine dating from the spring of 1992 has it as the company’s biggest current seller, edging out Police Quest 3, Leisure Suit Larry 5, and King’s Quest V. Its commercial performance was undoubtedly helped greatly by a fortuitous coincidence: the second biggest cinematic blockbuster of 1991 was a movie called Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves.

Despite her second game’s success, Marx left Sierra after its completion to return to writing for non-interactive media — a pity, as it seemed she was just starting to get the hang of writing and designing with interactivity in mind. If her trajectory had continued, her next game might have been amazing.

Important as adventure games still were for Sierra during this period, they were no longer the virtual sum total of the company’s offerings, as they had been for a period during the latter 1980s. For all that Ken Williams had entered the new decade determined to make Sierra’s name synonymous with interactive storytelling in the multimedia age, he was determined to diversify as well. By way of accomplishing that goal, Sierra announced on March 27, 1990, the acquisition of Dynamix, a small but well-respected Oregon-based development house that had been founded in 1984 and had since delivered an eclectic mix of original games and ports to various publishers. Of late, they had focused on the crazily disparate genres of 3D vehicle simulations and cinematic adventure games. With Sierra’s in-house developers having the latter category well in-hand, it was the former which most excited Ken Williams — even though he personally was something of a simulation hater. (“Are there any planes, tanks, or automobiles this industry hasn’t done fifty times already?” he had asked almost plaintively just before the Dynamix opportunity presented itself.) Dynamix soon showed him how wise he had been to go with his market research over his personal preferences by gifting Sierra with Red Baron, a superb World War I dog-fighting simulation that became their biggest non-adventure hit since the pre-King’s Quest years, even in the midst of an unexpected glut of similarly-themed games from other publishers.

With Dynamix delivering the goods for the hardcore joystick jockeys, Williams pushed his in-house teams to branch out from adventure games and produce what we today would call “casual” games, targeted at traditionally non-gaming demographics. In fairly short succession, Sierra churned out three separate volumes of Hoyle Book of Games, collections of classic card and board games named after Edmond Hoyle, the eighteenth century’s foremost authority on such matters. The release of special versions of these titles that were designed to run nicely on the black-and-white laptop computers of the day revealed exactly what sorts of customers Sierra was hoping to appeal to.

Another vaguely casual product was something called Jones in the Fast Lane, a computerized board game with a strong resemblance to the old family classic Careers that had first come to Sierra as an unsolicited outside submission. It could be played alone, but that was rather missing the point; it really wanted to be played with up to three others during a high-tech family board-game night. Fun in short doses, but a little too shallow and random to be given the status of classic alongside its likely inspiration, it nevertheless found two great patrons in Ken Williams and Bill Davis, the latter of whom personally shepherded the project to completion. In a measure of the priority it was given as a potential new direction, it became Sierra’s second-ever CD-ROM product, beating even the CD-based King’s Quest V to market. But it never sold all that well despite a big promotional push, and Sierra would never again make anything quite like it.

While casual games had dominated the non-adventure agenda for 1990, education was the big watchword of 1991. Throughout Sierra’s history, their interest in this market had ebbed and flowed. Sometimes they had gone after it enthusiastically, as when they had signed big licensing deals with Disney and Jim Henson of Muppets fame in the mid-1980s; other times, not so much, although, as releases like Mixed-Up Mother Goose and the pseudo-educational gloss that was often placed on King’s Quest show, they never entirely abandoned the market. Now the educational tide was flowing back in again, with Ken Williams having decided that the audiovisual potential of the latest computers would make such products much more appealing to parents and educators. Thus the new “Sierra Discovery Series.” Corey and Lori Ann Cole, the husband-and-wife team behind the successful Quest for Glory adventure series, agreed to take a year off from that series to each design an educational product. The former made the middle- and high-school-focused Castle of Dr. Brain, the latter the elementary-school-focused Mixed-Up Fairy Tales. And other “educational adventures” were in the works for a 1992 release.

Sierra’s pitch for this latest educational initiative was designed to address the permanent existential angst/guilt of modern parents: the fear that their children watched too much television. Educational adventures offered a healthier alternative that wouldn’t be any more taxing on the parents and that would be even more appealing to the children themselves.

Why do children spend so many hours watching TV? This is a question you often hear from concerned parents and teachers. The answer is simple: because the world of TV is one of color, fun, and adventure. It’s an escape from the child’s everyday world. Who wouldn’t want that? But many people are concerned about the passive nature of TV watching. It just isn’t that stimulating for children’s minds.

What if there were something else the child could be doing? Something with equal color and sound and fantasy, but this time the child could jump right through the screen and into the action? Better yet, what if the child could actually learn something while having fun? If you have a personal computer in your home, you already have the first ingredient for enriching your child’s everyday life.

What harried parent could refuse a pitch like that?

While the individual products did more or less well, Ken Williams must have been at least somewhat gratified when he glanced at that aforementioned sales chart for the spring of 1992. Yes, the top four items on the list were all conventional Sierra adventure games — but, tellingly, none of the remaining six titles were.

In all of these initiatives, Williams was chasing a vision of computer gaming’s future which stood in marked contrast to that of many of Sierra’s peers. Even as they hunkered down in the face of the ongoing Nintendo storm to focus on the games and the gamers that had gotten them this far, Sierra chased a broader, more inclusive vision of interactive entertainment — chased a near-future with something for everyone in the stereotypical suburban family. In the Sierra household of Williams’s dreams, 14-year-old Johnny would play Castle of Dr. Brain at school and Space Quest at home; nine-year-old Mary would play Mixed-Up Fairy Tales at school and King’s Quest at home; Dad would play Hoyle on his laptop on business trips; Mom and Dad together would put in some quality time with Leisure Suit Larry in the evenings after the kids were in bed; and the whole family would gather in the living room on a Sunday afternoon for a game of Jones in the Fast Lane.

In keeping with this vision, Sierra’s design staff too was shockingly diverse by the standards of their industry. At one point in 1991, four different women were designing games for Sierra; I’m hard pressed to come up with another developer that was employing even one female designer. Ken Williams wasn’t particularly idealistic, and he certainly was no social activist; he was merely a businessman who believed that he needed to expand the appeal of his products in order to grow his business. Nor did his version of inclusivity extend overly far; his insistence that Sierra’s white-bread games were premium entertainment products, with prices to match, ensured that. Nevertheless, Sierra stood out from the pack of other publishers who were all tripping over each other as they chased after the same group of 12-to-35-year-old single white males.

Ken Williams didn’t keep his vision to himself. Quite the contrary: on the theory that a rising tide lifts all boats, he pushed the other publishers to broaden their own views of who constituted a potential customer. He railed ceaselessly against what he saw as the needless complications of being an MS-DOS gamer: of needing to know a dozen technical terms just to read the minimum specifications printed on a box and thereby know whether your computer could run any given game; of needing to know how to swap expansion cards in and out and configure their IRQ settings; of needing to know how to get around in MS-DOS itself, how to configure extended and expanded memory and set up a custom startup script for almost every new game you purchased. He believed — correctly, it seems to me — that all of these technical complexities restricted the market for computer games to the sorts of personalities who reveled in them, preventing entire potential genres of computer entertainment from ever being explored. As head of the Software Publishers Association Standards Committee, he pushed his colleagues to adopt a standard nomenclature for listing system requirements, and pushed them to adopt a voluntary Hollywood-style standard for rating game content as well before one was imposed on them from outside the industry; he succeeded in the former task, but, for the time being anyway, failed at the latter. He was thrilled when a consortium led by Microsoft published, after much lobbying from him among many others, a standard set of minimum specifications for a so-called “Multimedia Personal Computer. ” The idea behind it was that a customer could purchase a system with the MPC logo on the box and then know that she could purchase any piece of software sporting the same logo in the assurance that it would work on her computer — no muss, no fuss, no parsing of fine-print technical specifications.

Sierra’s most obvious ally in their mission to broaden the demographic for home-computer software was Broderbund. The two companies bore many similarities. Both had been formed way back in the dark ages of 1980 — Broderbund under the alternate spelling of “Brøderbund” — and both remained at bottom family businesses, run by the Williams family in the case of Sierra, by the Carlston family in the case of Broderbund. The Williamses and the Carlstons had been close friends in the early days of what Doug Carlston referred to as the “software brotherhood,” and a certain sense of kinship between these two rare survivors of that formative period had managed to carry through into this very different era of the early 1990s, as had a similar philosophy about the future of their industry. To if anything an even greater extent than Sierra, Broderbund was actually succeeding in the mission of putting their products into the hands of Middle America at large. Their Carmen Sandiego series constituted the most successful edutational products of their time, so popular that Broderbund was putting the final touches on a deal to bring it to television as a children’s quiz show. Their Print Shop posters and banners were an inescapable presence at pot lucks, weddings, and school dances from sea to shining sea. They distributed SimCity, a game which had recently caused a sensation in high-brow newspapers and magazines that normally had no interest in such things. And, if you insisted on a traditional videogame perfect for the traditional teenage-boy player, they had Prince of Persia, a massive platform- and world-spanning hit of the sort that other computer-game publishers — even the similarly-inclined Sierra — simply didn’t produce in those days.

Following the collapse of Mediagenic, Sierra and Broderbund vied for the title of second-biggest publisher of consumer software, trailing only Electronic Arts; this fact alone must stand as strong evidence for the assertion that their shared strategy of broader outreach was a wise one. It therefore sent a shock wave through the industry when on March 8, 1991, Sierra published a blandly written press release stating that the two companies intended to merge. Such a merger would create by far the biggest company in the industry — by far the biggest, most powerful company the industry had ever known.

Looked at strategically, the merger made a lot of sense for reasons beyond the sheer size of the behemoth it would create. Broderbund had never been strong in adventure games, and felt unequipped for the merger of Hollywood and Silicon Valley which everyone, not least Ken Williams, insisted was at the very least a big part of the inevitable future of computer gaming; Sierra, by contrast, had been the first name in graphic adventures for more than a decade, and had invested heavily in that anticipated future. Broderbund also lacked the expertise in high-performance simulations which Sierra had acquired through Dynamix; such hardcore products might not be the most important aspect of the future envisioned by the Williamses and the Carlstons, but all signs pointed to them remaining a solid profit center for a long, long time to come. For their part, Broderbund had managed to create, through careful product curation and brilliant marketing, no less than four of the sort of immediately recognizable Middle American brands which Sierra so coveted, in the form of the aforementioned Carmen Sandiego, The Print Shop, SimCity, and Prince of Persia; the only remotely comparable brand which Sierra possessed was King’s Quest. Broderbund, then, needed Sierra’s technology; Sierra needed Broderbund’s brands and branding expertise. It seemed a match made in heaven.

But then, just three weeks after the merger was announced, another press release stated quietly that it had fallen through. The two parties said that, while they still held one another “in the highest regard,” they just hadn’t been able to come to an agreement on the terms of the merger. The reasons aren’t hard to divine. For all the historical, strategic, and philosophical parallels between the two companies, internally they were very different places. Ken Williams may have changed his public image dramatically since the days when he had played the role of the software industry’s Hugh Hefner, peddling Softporn to the nation’s youth from his Jacuzzi, and Sierra too may not have been playing host to quite the same number of wild parties as in the early days, but it remained a free-wheeling place cast in the image of its hard-charging, gleefully profane boss. The Carlstons, meanwhile, were a religious family, the children of a theologian, clean-cut and clean-living, and the rest of their company had largely followed their example. Officially, the deal would have been an acquisition of Broderbund by Sierra, although both parties were careful to state that this was just to satisfy the financial folks — that it was really a merger of equal partners. Still, word filtered through the industry grapevine that Ken and Roberta Williams had acted like they “owned the place” when they dropped in on Broderbund for a visit, angering the staff there. The Carlstons, who to their immense credit always walked the walk more than they talked the talk of Christian morality, valued their employees like extensions of their own family, and grew deeply concerned when Ken Williams shifted the discussion to possible “redundancies.” Soon after, they apparently nixed the deal.

Had it gone off, the merger would have created a more dominant entity than our own timeline’s consumer-software industry has ever produced. As such, it provides an intriguing ground for what-if speculations — even if, what with absolute power corrupting so absolutely, it was probably better for the industry as a whole that it never happened.

Even as it was, though, Sierra had little room to complain about the state of their business in the first couple of years of the 1990s. Their gross revenues increased by $6 million for the fiscal year ending on March 31, 1991, topping $35 million. The following fiscal year, they increased even more, to $43 million, with the company remaining healthily profitable throughout the period despite major ongoing investments in research and development. By any standard, they were on an admirable upward trajectory, having made more money than the last every year since fiscal 1985, having been profitable since fiscal 1987. Once CD-ROM dropped — it had to someday, right? — who knew how high they could soar.

But CD-ROM wasn’t the only aspect of home computing’s shiny future on which Sierra was banking. Ken Williams had gotten the online religion, and here too Sierra was jumping in with both feet. Next time, we’ll turn our attention to that great adventure.

(Source: Sierra’s corporate magazines from Fall 1989, Spring 1990, Summer 1990, Fall 1990, Spring 1991, Summer 1991, Fall 1991, Spring 1992; Computer Gaming World from March 1991, May 1991, and June 1991; press releases, annual reports, and other internal and external documents from the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play. And my thanks go to Corey Cole, who took the time to answer some questions about this period of Sierra’s history from his perspective as a developer there.)