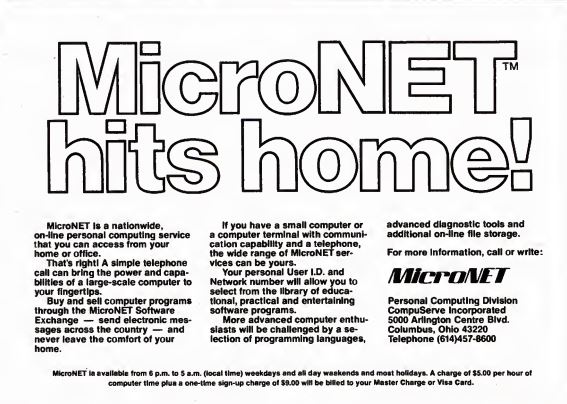

Right from the beginning, games were a component of the commercial online services that predated the World Wide Web; both The Source and CompuServe included them among their offerings from the moment those services first went online. In the early years, such online games were mostly refugees from 1970s institutional computing. Classics like Star Trek, Adventure, and Hammurabi had the advantage of being in the public domain and already running without modification on the time-shared computer systems which hosted the services, and could thus be made available to subscribers with a minimum of investment. Eventually even some text-only microcomputer games made the transition. By 1984, CompuServe, now well-established at the vanguard of the burgeoning online-services industry, had a catalog that included the original Adventure along with an expanded version, nine Scott Adams games, and the original PDP-10 Zork (renamed for some reason to The House of Banshi). And those were just the text adventures. There were also the dungeon crawls Dungeons of Kesmai and Castle Telengard and the war games Civil War, Fantasy, and Command Decision, while for the less hardcore there were the CompuServe Casino, board games like Reversi, and curiosities like a biorhythm charter and an astrology calculator.

The fact that so many games were on offer so quickly indicates that they must have paid their way, at least to some extent. The hard reality remained, though, that these single-player games which happened to be played online were a hard sell to many subscribers. Paying $6 or more per hour to play a text-only game didn’t make a whole lot of sense to many of them when they could buy or even type in something just as satisfying for their local machines.

Group discussion about games, on the other hand, was something only the online services could offer with any degree of convenience or regularity, and it absolutely thrived in consequence almost from Day One. Adventure games were an especially popular topic, and for very good reason; given the non-sequiturial puzzles those early adventures were so rife with, outside help was about the only way most players had a reasonable chance of solving many of them. When Sierra in 1982 released perhaps the most absurdly unfair early adventure of them all in the form of Time Zone — twelve disk sides and more than a thousand rooms of complete inscrutability — The Source’s users mounted a pioneering crowdsourced effort to solve it. Its home was called The Vault of Ages:

Welcome to the Vault of Ages. Here we are coordinating the greatest group effort in adventure-solving: the complete mapping of On-Line’s Time Zone.

Herein we are gathering, verifying, and correlating information about each time zone. Feel free to visit here anytime, but remember that for the Vault to fill, we need your contributions of information. Any time you have new information about mapping, puzzle solutions, traps overcome, items found, email this info to me. After verification, your contributed jigsaw-puzzle piece will be added to the Vault file, and your name will be entered upon the rolls as a master solver.

Unsurprisingly, the first person known to have solved Time Zone, a tireless adventure fanatic and gaming journalist named Roe R. Adams III, was a Source and Vault of Ages regular.

The online services would continue to be a vital meeting point for gamers, gaming journalists, and, increasingly, the developers that made the games for many years to come, right up until they were superseded by the modern World Wide Web. Countless gamers who weren’t subscribers nevertheless benefited from the walkthroughs and strategy guides that filtered down from the likes of CompuServe onto the network of local bulletin-board systems and into the halls that hosted users-group meetings, to eventually be passed from hand to hand on playgrounds and in lunch rooms as smudged printouts whose unassuming appearance belied the precious information they contained.

But, while it’s certainly noteworthy in itself, our main concern today isn’t with this far-reaching game-solving grapevine. We’re rather concerned with the games that subscribers were actually playing online in increasing numbers by the middle of the 1980s — games which by and large weren’t the roll call of golden oldies that opened this article. We’re interested, in other words, in how the online services learned to take advantage of their uniqueness as interconnected real-time communities of tens or hundreds of thousands of people to offer players something they couldn’t get from an offline game. In doing so, they would give the world a sneak preview of its online future in yet one more way.

One of the executives who worked under Jeff Wilkins at CompuServe in the early 1980s was named Bill Louden. He was an unusual character there in several ways, not least in being a living embodiment of where computing was going as opposed to where it had been. Unlike most of CompuServe’s management, who had been raised at the bosom of institutional computing, Louden had come to his current job through microcomputers. He had been working as a Radio Shack store manager in CompuServe’s hometown of Columbus, Ohio, when the TRS-80 arrived in 1977, and he became such an instant home-computing zealot that he founded the Central Ohio TRS-80 Users Group shortly thereafter. He joined CompuServe in 1979, hired by Wilkins to be a bridge between the hobbyist-oriented personal-computing community which he knew so well and the dominant culture of business-oriented big-iron computing inside CompuServe.

Among the many things which Louden understood but CompuServe’s other managers largely did not was the appeal of games. He became the foremost advocate for them inside the company — an advocate for, that is, going beyond just scooping up the low-hanging fruit of Adventure and Hammurabi and calling it a day. He believed that games, if given the proper priority, could become not just an occasional distraction for the service’s subscribers but the primary reason some of them chose to sign up in the first place. By acting upon that belief, he would become another forgotten pioneer, one of the most important architects of online gaming’s future.

The first of Bill Louden’s pet projects to hint at the true potential for online gaming was at first glance just another tired institutional refugee. Back in 1978, a new game had appeared on the DEC PDP-10s that lived at the University of Texas at Austin. DECWAR was at bottom yet another variation on the tried-and-true Star Trek strategy game, but some of its embellishments to the formula were very significant. Instead of a single player hunting computer-controlled Klingons and Romulans, DECWAR had room for up to eight players, who faced off against one another in two teams of four, with the balance of the teams filled up by the computer when fewer than eight humans could be rounded up. Just as significantly, the game was played in real time.

DECWAR first came to Bill Louden’s attention in 1982; he saw the potential it held for CompuServe immediately. Making inquiries with the university, he found the game’s developers were willing to sell him its source code for $50. When his superiors refused to part with that princely sum, he bought the source himself using his own money. Louden then did much of the work that was required to adapt the game to CompuServe himself, excising in the process the last vestigial remnants of the Star Trek intellectual property. (Out of similar legal concerns, the original Star Trek game had itself become the thinly veiled Space Trek on CompuServe by this point.) Louden also added innovations like a leader board which saw players progress in rank from cadet to admiral as they won games and blew up other players’ ships, adding at least a dollop of long-term persistence to tempt them to keep playing. And he gave DECWAR a new name: MegaWars.

CompuServe advertised MegaWars widely for the first year or two, even as their marketers ignored other pioneering initiatives like CB Simulator. Garish MegaWars depictions like these contrasted strangely with the company’s usual staid image. (One can only imagine what those members of the board who had been against launching the consumer service from the start thought of this sort of thing.) As was par for the course during this time period, the imagery of the advertising had almost nothing to do with the game, which featured neither interpersonal combat nor scantily-clad warriors of either sex.

MegaWars went up on CompuServe circa August of 1982, much to the dismay of the University of Texas’s student coders, who had neglected to copyright or attach any legal restrictions whatsoever to the source code they had given to Louden for $50. Playing it was a daunting proposition: it usually required about two to three hours — meaning as much as $20 in connection fees — to finish a complete match, and the player had to learn 32 separate textual commands, which had to be typed in real time as the galaxy exploded in battle all around her. Yet, despite or because of its challenging nature, it proved enduringly popular, spawning a cult of hardcore players who stuck with it for years and years. In fact, it would become CompuServe’s most durable single game of all, remaining on the service for the next fifteen years. “The people that play MegaWars are extremely serious,” CompuServe’s communications director was soon warning. “The expertise level is very high.”

It didn’t take long for MegaWars players to form themselves into consistent teams that themselves sometimes stayed together for years. Intra- and inter-team politics could come to fill as much space as actually playing the game. Team Dune, for instance, was made up of fans of Frank Herbert’s iconic series of science-fiction novels; everyone on the team was expected to take the name of a Dune character as a handle. “Dictators” were selected from among the team’s members for three-month terms in hotly contested elections that could sometimes turn violent. It was all a part of the fantasy. A Team Dune member named Martin Maners, better known on CompuServe as “Leto II,” had this to say:

I’ve always had a vivid imagination. I like science fiction and Star Wars. When you sit down in front of your computer and play MegaWars, you really leave the earth, you’re really out there. It helps me relax, especially with the way MegaWars lets me talk to other players on my team. It’s nice to be able to sit back and do something completely different for a change.

With MegaWars, Bill Louden had put his finger on the real strength of gaming on a service like CompuServe: the opportunity for subscribers to play against one another rather than alone with the computer. “MegaWars is a challenge and is entertaining as well, but the real enjoyment comes from the multiplayer aspect of the game,” said one subscriber. “Interacting with other human players is what makes it interesting in a way that a ‘man vs. computer’ game just can’t match.” Another subscriber noted that it was “not like a game you would run on your personal computer. Here you get to pit yourself against a real person who could be across the street or the country. A much more formidable foe! It’s both entertaining and challenging, and at the same time it’s a great way to meet people and make new friends.”

If CompuServe was to continue to develop their games in this direction, however, they would need to move beyond public-domain institutional refugees like DECWAR/MegaWars. Luckily, Louden had recently been fielding inquiries from a pair of outside programmers with aspirations to do just that. They called themselves Kesmai.

Kesmai weren’t your stereotypical teenage bedroom coders. John Taylor, who had a masters degree in computer science, worked for General Electric’s High Performance Division, writing software for industrial robots, while Kelton Flinn was working on a PhD in applied mathematics at the University of Virginia. They picked their company’s name as their favorite from a long list of random ones that had been spit out by a name-generating program.

Several years before, while still an undergraduate, Flinn had written a very ambitious game on his university’s computer which combined Star Trek-like space combat — played in real time, no less! — with a conquer-the-universe strategic layer of economics and politics. He called it simply S. He remembers one particular incident as the turning point in its development: “One person’s favorite planet was taken, and he picked up a chair and stalked across the room with it to clobber the culprit. ‘Bob, put the chair down, it’s only a game…’ I guess I should have known then we had a potential hit!”

After much lobbying on Kesmai’s part for a development contract, Bill Louden agreed to let them bring S to CompuServe as a sort of trial project, renaming it in the process to MegaWars III. (MegaWars II had been an ill-fated attempt to add graphics and sound, at least of a sort, to the first MegaWars using the character graphics and simple bells and whistles allowed by some otherwise textual communications protocols. Dismissed by Louden himself as “poorly done and abysmally slow,” it didn’t last very long.) Kesmai greatly expanded on the already ambitious S template for CompuServe, making the universe much larger, adding more diplomatic options, and adding a veritable sub-game all its own of starship design. It seems safe to say that, by the time they were done, there was nothing of comparable complexity available even in single-player form on the microcomputers of the time. Indeed, the end result can’t help but remind one of the so-called “4X” games — “explore, expand, exploit, exterminate” — that wouldn’t become really practical on PCs until the early 1990s, when the steady march of technology would lead to strategic epics like Civilization and Master of Orion. In contrast to most of those later games, though, MegaWars III offered all the unpredictability of dozens of human opponents, with whom one could communicate at any time using “hyperspace radio,” whether to make or break trade deals and military alliances or just to shoot the breeze.

A single game of MegaWars III could host up to 100 players, and ran for four to six weeks. At the end of that time, the player who had earned the most points through conquest and the economic development of her colonies would be crowned emperor (this system would later be cheerfully nicked by Master of Orion as one of its own victory conditions, thus further cementing the similarities between the two games). With a victor thus declared, it would be time to wipe the slate clean. A brand new universe would be generated, and players who had been disappointed by their performance last time could try their luck on this new playing field. Some modern online games could perhaps take a lesson from this constant rolling-over of the virtual universe, which was done with conscious intent: Louden notes that it “kept newbies from feeling they had no way to catch up and were just meat for the slaughter.”

That said, little else about MegaWars III was forgiving; it was even more demanding than the game to which it had been billed a sequel. Eight hours of real time corresponded to about a month of game time. Those who hoped to have a shot at the winner’s circle knew that they had to sign on every night, sometimes for hours at a time, to maintain their empires. The subscriber known as “L’Eagle,” a self-described “corporate lawyer” in real life, became something of a community legend for winning the very first game of MegaWars III, which ran from January 19 until March 15 of 1984. He was already a veteran grognard at that time, with a history with war games which dated back well into the previous decade. For someone like him, MegaWars III provided an experience that could only have been approached in the past by some of the more elaborate play-by-mail campaigns run by companies like Flying Buffalo. The CompuServe version, however, had the added allure of instant feedback, along with the instant gratification of real-time chat — always useful for taunting a vanquished foe.

Just as with the first MegaWars, interactions with other players in MegaWars III were, even more so than all of the complicated rules, the heart of the game’s appeal. L’Eagle described the game, with its delicate tissue of alliances, in terms that actually smack as much or more of Diplomacy as Master of Orion. Such is the effect of adding the human element to the 4X equation.

The game has very few limitations. That’s part of the charm. But everyone has to work to keep the game good-spirited. At one point, the game’s authors thought that team members would turn on one another, that friends would become enemies. But after six weeks of planning together, the last thing you would do is back-stab.

L’Eagle is perhaps overstating the case just a bit. Back-stabbing was hardly unknown in MegaWars III; in fact, just as in Diplomacy, it was a virtual necessity for those with serious aspirations to win. Still, MegaWars III co-creator Kelton Flinn wasn’t wrong when he noted that “it’s a social game, as well as a competitive one.” Already in 1984, the year of MegaWars III‘s debut, CompuServe hosted a gathering of players in Columbus that attracted several dozen attendees. It was only the first of many.

Journalists, conditioned to think of computer games as strictly kids’ stuff, frequently expressed surprise when they were informed that the average age of a hardcore MegaWars I or III player was somewhere north of thirty. Really, though, it couldn’t have been any other way. The great disadvantage of these early online services, the necessary temper to any nostalgia for the era of the net before the Web, was how expensive they were. The whole time you were playing, the meter was running. Just as with CB Simulator, some people got addicted to the games, often to the detriment of the rest of their lives. Regulars soon noticed cyclical patterns to some of their comrades’ comings and goings. L’Eagle:

You can tell when the MasterCard bills come. People disappear. Later, they come back and say, “Yeah, I just had to cut down a bit.” Teenagers, you might never see them again. Fortunately, I make a lot of money.

As always, digital utopianism only got you so far in a world that at the end of the day still ran on money.

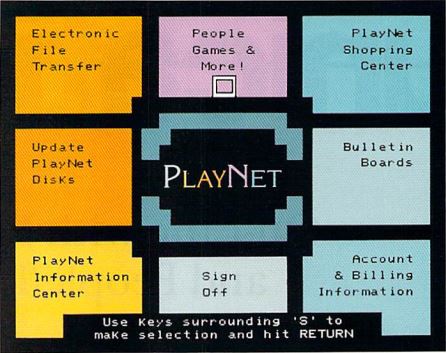

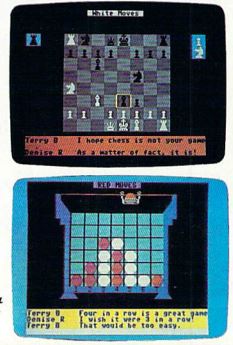

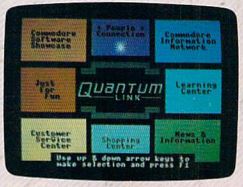

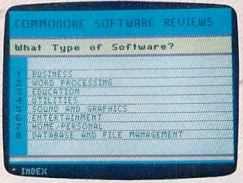

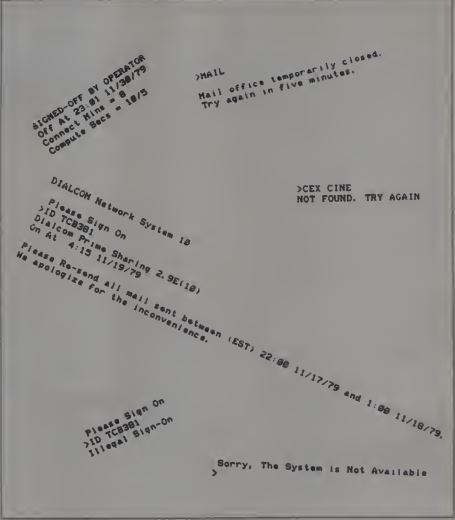

By mid-decade, then, multiplayer gaming — as opposed to the older species of single-player games that happened to be played online — was establishing itself as a staple of online life, not only on CompuServe but also on services like PlayNet and QuantumLink. As we saw in an earlier article, the latter pair offered a variety of simple board games that more casual players could enjoy with the added benefit of graphics, an area CompuServe would soon push into as well. The potential of online games remained sharply limited, however, by the fact that the vast majority of subscribers to the various services were still using 300-baud modems, which transferred data at the glacial pace of approximately 30 to 35 bytes per second — or a little over 2 K per minute.

When that logjam finally broke, it did so, as so often happens in technology, with head-snapping speed. The breakthrough was helped along by GEnie, the new online service which launched in October of 1985 to become the most serious challenger yet to CompuServe’s dominance. A big drag on the adoption of faster modems had actually been CompuServe itself, which charged $6 per hour for 300-baud access but a well-nigh absurd $12 per hour for 1200-baud connections. GEnie, on the other hand, launched at $5 per hour for both 300 and 1200 baud, soon forcing even the industry leader to adjust their own rates in response. With a new standard pricing model thus established, subscribers rushed out to buy the new, faster modems that were also coming down rapidly in price. GEnie reported at the beginning of 1986 that less than 40 percent of their subscribers had upgraded to 1200 baud; by the end of the year, that number had topped 90 percent. And 1200 baud was itself only a beginning rather than an end: 2400 baud was coming on strong, with 9600 baud out there on the not-too-distant horizon. What might developers of online games be able to do with those sorts of connection speeds? Bill Louden and the boys at Kesmai had some ideas.

Louden had left CompuServe in 1984, disaffected by what he saw as too many “corporate people” encroaching on his domain. After some misadventures trying to set up a regional online service of his own called Georgia Online, he was tapped by General Electric to run GEnie. Like any good manager of an upstart, he surveyed the leading company in his industry — i.e., his recent employer CompuServe — for weak spots where GEnie could offer something more to customers. As we’ve just seen, one of these was making higher-speed connections affordable. Another, unsurprisingly given Louden’s reputation as the “games guy” even while he was still at CompuServe, was games. Louden strove to make GEnie a haven for gamers, both for talking about offline games — the service would verge on displacing CompuServe in the years to come as the foremost source for walkthroughs and strategy guides — and for playing online games.

For their part, Kesmai were happy to work for any service willing to pay them. The fact that John Taylor was still going to work every day at GEnie’s corporate parent General Electric, not to mention Kesmai’s established relationship with Louden, made a development contract with the new service a natural step. MegaWars III therefore soon came to GEnie as well in thinly disguised form as Stellar Emperor. But that was merely an old CompuServe glory being revisited. GEnie’s crowning gaming glory would be a radical departure from anything seen online to date.

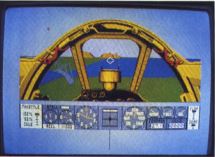

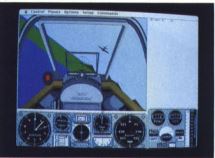

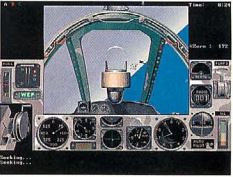

Air Warrior, a multiplayer air-combat simulator using aircraft from both of the world wars, was first offered to owners of the Apple Macintosh in late 1986. Although the game ran through GEnie, it was provided as a standalone application which handled all of the minutiae of logging in and communications for itself, in lieu of the text-only terminal programs subscribers normally used to access the service. This approach allowed it to make use of cutting-edge 3D graphics, the likes of which had never before been seen in an online context. It was nothing short of revolutionary, the very first game of its kind, and those who wished to play it had to pay for their spot at the bleeding edge — to the tune of no less than $11 per hour, more than twice GEnie’s normal going rate. Luckily for Kesmai, who had expanded greatly and invested a lot of money in the project, a fair number of well-heeled users proved willing to pony up.

Ported to the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST in 1987, Air Warrior used what we today would call the “software as a service” model to perpetually evolve throughout its long lifespan, with players expected to download the updates which appeared almost monthly on GEnie and merge them into their local disks. By 1988, this process had brought the game to a certain maturity. Three “theaters” — one for World War I, two for the more popular World War II — were kept in constant operation, complete with leader-board tallies of aircraft shot down and ground targets destroyed. Similarly to MegaWars III, a winner of each campaign was declared every three weeks and the theater reset to keep anyone from running away with things for too long.

During a campaign, players could cast their lot with any of three opposing militaries. Some players preferred to be lone wolves, Red Barons lurking in the cloud cover to swoop down on their prey, but most took it upon themselves to further organize into squadrons, with all the resultant social interaction you might expect. Indeed, Air Warrior became more and more team-oriented as time went on. Lumbering B-17 bombers took off on strike missions with not only a pilot but no fewer than six other players filling the various gun turrets, escorted by more players in single-seater Mustangs and Spitfires. Meanwhile still other players would be mounting a coordinated ground assault in jeeps and tanks. All were bound together by the magic of chat — or, in in-game terms, by their multi-band radios. And on the other side, of course, was a similarly well-coordinated group of defenders hoping to add to their point tallies by taking down some of those juicy B-17s.

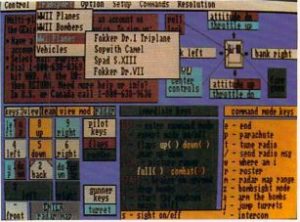

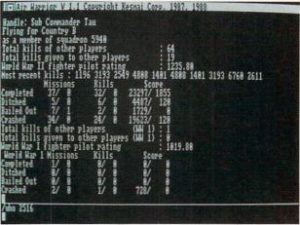

The Air Warrior application incorporated a terminal layer for handling logging into GEnie and other command-oriented tasks. Here a player is checking out his personal history.

The obvious forerunner to modern multiplayer wargasms like the Battlefield series, Air Warrior was distinguished, like so many of these early online games, by a devotion to the game’s fiction that would be very foreign to most of today’s eager gibbers and fraggers. Air Warrior billed itself as a flight simulator the equal of the ones being made by companies like subLogic and MicroProse, and many players took it very seriously indeed on those terms, implementing historical tactics and even radio protocols. Inevitably, some new players tried to single-handedly run roughshod over the place, but such respectless cretins usually didn’t live very long; one sign of the game’s worth as a simulation was the fact that the historically accurate tactics were mostly the ones that worked. And of course the fact that you were paying $11 per hour for the privilege had a way of driving up the average participant’s age and assuring that only those who really, really hankered after a vintage air-combat experience stuck around.

In the air in Air Warrior. Note the chat window, vital to squadron coordination, that’s open to the right.

Newbie pilots wishing to find acceptance within a squadron’s ranks had to contend with the realistic flight mechanics while tranquilly accepting their designated role in each operation; true to history, new pilots were usually given sheltered positions as wingmen to more experienced fliers which gave them little opportunity to run up their personal kill tallies. Still, greenhorns quickly learned to appreciate the extra cover, as nothing about Air Warrior was forgiving. Woe betide the pilot who forgot that the escape key was meant literally in this game: it led to an instant, no-questions-asked bailout.

Death meant that you had to start over with a new character, so all serious players practiced their wheels-up landings and their water ditchings extensively using the game’s weapons-less offline practice mode. Even the effects of fuel usage were modeled accurately; planes became faster and more maneuverable as they got lighter. But this too, of course, was a double-edged sword: many an Air Warrior pilot wound up dead because of inattention to the fuel gauge. To help the youngsters out, the experienced pilots instituted a flying-and-tactics clinic which ran every Thursday night for years. The life saved, they reasoned, might just be their own if they got saddled with one of these greenhorns on their wing.

In marked contrast to the Kesmai games that had preceded it, Air Warrior remained always on the cutting edge of audiovisual technology. It shone most of all on the Amiga when that machine was the audiovisual class of the industry; it wasn’t even ported to MS-DOS until 1989. Once there, though, it continued to evolve apace, becoming in early 1993 one of the first games of any stripe to support the new generation of “Super VGA” graphics cards. The Air Warrior community would always remain a relatively small one; a 1993 magazine report describes about thirty players active in each theater most evenings, the very same number cited by another report from 1989. But despite such limited numbers of active players, Air Warrior became, like the MegaWars games, rather astonishingly long-lived, actually managing to outlast its original host service GEnie to make it all the way to 2001. For those seeking a certain kind of historically grounded multi-player combat experience, emphasizing real-world tactics, it was in many ways a better take on online gaming than most of what’s available today. And even for those who didn’t know the difference between a Hellcat and Zero, it remained a living example of the potential for online gaming, an aspirational ideal at the vanguard of the field for many years.

While it may be a little hard to recognize today, the SVGA Air Warrior looked spectacular in its day — not just spectacular for an online game, but spectacular, period.

This survey, sketchy though it’s been, has hopefully been enough to demonstrate both how influential the online services of the 1980s really were on online gaming as we know it today and how compelling the games they offered could be even when taken entirely on their own terms. Yet the creations we’ve seen so far, groundbreaking though they’ve been in their various ways, have all been relatively short-form experiences: games with beginnings, middles, and ends that spanned no more than a handful of weeks. What persistence these games did possess was thanks to players like the desert rats of Team Dune, who found ways to make the fiction last even when the game proper was over. But what of games which truly have no ending? What of games which aren’t so much games at all as virtual worlds, even virtual societies — real Second Lifes for their inhabitants, one might say. Today such virtual worlds consume the free time of millions of rabid players, and stand as the most complex virtual spaces ever created. Next time, then, we’ll find out how game developers discovered the power of persistence, many years before Warcraft — much less World of Warcraft — was a twinkle in its creators’ eyes.

(Sources: the books On the Way to the Web: The Secret History of the Internet and its Founders by Michael A. Banks and Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution by Steven Levy; Softline of May 1982; Online Today of June 1987, January 1988, and February 1989; Byte of September 1982; Antic of November 1984; Compute!’s Gazette of May 1985; Family Computing of June 1986; InfoWorld of October 21 1985 and December 2 1985; Compute! of July 1987; Amazing Computing of August 1987 and March 1989; the STart “games issue” for 1988; Computer Gaming World of January 1990 and May 1993; CompuServe’s games catalog/brochure from 1984; the Games of Fame online articles on MegaWars and MegaWars III; the history page from a recent MegaWars revival.)