I first read Piers Anthony’s thick 1969 novel Macroscope when I was in my early teens, and haven’t returned to it since. Nevertheless, I still remember the back-of-the-jacket text on my dog-eared old first paperback edition: “Existence is full of a number of things, many of them wondrous indeed — and these are the things of this soaring novel.” This high-flown blurb has remained so memorable to me because it’s so unlike anything anybody would ever write about Anthony’s work today.

Piers Anthony was born in 1934, and first made a name for himself in literary circles as one of the slightly lesser lights among science fiction’s New Wave of the 1960s. He was no Roger Zelazny, Ursula Le Guin, or Harlan Ellison, but he was regarded as a modestly promising young writer in his own right; he even contributed a story to the second of Ellison’s landmark Dangerous Visions anthologies in 1972.

But that honor, along with Macroscope, which became his second and last novel to be nominated for a Hugo award in 1970, actually mark the high point of Anthony’s respectable literary career. It had always been difficult for him to pay the bills as a second-string writer of serious speculative fiction, and it only grew more difficult as the luster faded from the New Wave in the 1970s and his books attracted even less attention. He was saved from a perhaps not-undeserved obscurity by Lester del Rey, one of genre fiction’s most legendary editors and curators. As the first to nurture and publish such writers as Stephen R. Donaldson, Terry Brooks, and David Eddings, del Rey became largely responsible for the post-Tolkien, post-New Wave boom in epic fantasy fiction. But, apparently seeing a different set of strengths and weaknesses in Anthony than he did in those other charges, del Rey guided him down a rather less epic path. Thus in 1977 Anthony came to write A Spell for Chameleon, the first novel in an endless series of them set in the pun-infested light-fantasy world of Xanth.

A Spell for Chameleon certainly wasn’t the worst fantasy novel to be published that year. While it had nothing of any substance on its mind whatsoever, its very lightness made it a welcome alternative to the likes of the three other writers I’ve just mentioned, whose books came complete with all the labored self-seriousness of an Emerson, Lake, and Palmer album. The fact is, there really wasn’t much else like A Spell for Chameleon on bookstore shelves in 1977; it felt like a genuine breath of fresh air.

Unfortunately, that book was as good as Xanth ever got. When it became the best-selling novel he had ever written by far, Anthony recognized it for what it was: a formula for maximum sales with minimum labor investment. And from that point on, he never looked back.

Still, even the first few Xanth novels after A Spell for Chameleon weren’t horribly written by the standards of their kind. Eventually, though, Anthony decided that such niceties as editing were incompatible with his desire to publish one of them every year, along with two or more other books from his other series. In time, he admitted to writing his novels using a “template” in his word processor — ah, the wonders of technology! — that he needed merely fill in, Mad Libs-style. He was actually able to outsource much of the writing to his readers, by inviting them to submit their own jokes and plots and character outlines. But where the rubber meets the road, in the form of sentences on the page, none of these assistants could make up for his refusal to take the time to be any good at his craft. There are sentences in latter-day Anthony in particular which are simply appalling from a writer with decades of experience. Consider, for example, this extract: “So why would I break with him? Because I came to the conclusion that he was a loose cannon. The problem with such a cannon is that it is more dangerous to its friends than to its enemies. I had suffered such looseness before…” If ever a court is established for crimes against the English language, Piers Anthony ought to be one of the first writers it indicts.

Between 1977 and today, Anthony has churned out no less than 42 Xanth novels, with another four reportedly complete and merely awaiting release as of this writing. And in between all those Xanth novels, he’s written dozens of other books. His guiding principle appears to be that not one word he writes should ever be put to waste; he wants somebody to pay for every last stroke of the keyboard. Thus he’s written two rambling, unfocused “autobiographies” which seem to be composed of journal extracts and “how to be a successful writer” advice columns he wasn’t able to place anywhere else. And thus when he wrote a series of letters to a twelve-year-old Xanth fan who had been paralyzed in a car crash, he irretrievably tainted the kindness he had evinced in doing so by compiling all of them into a book and publishing that too.

Anthony’s great stroke of genius for promoting all of these books came right out of the modern social-media playbook: he built his brand out of himself, building a cult of personality that superseded pesky details like the quality of his prose or the originality of his plots. For most people, Xanth fandom has a definite expiration date; it generally begins in one’s preteen years, and is over around the time one learns to drive a car. Within that window of time, however, many youngsters are all in for Xanth, and this is due not least to the connection they feel to its mastermind. Early on, Anthony took to appending an “author’s note” to each of his novels, in which he mused about the circumstances of its creation. That anyone, much less impatient youngsters, should have found these interesting was rather bizarre on the face of it. Anthony didn’t travel much or have adventures in the real world or build or do unusual things. He mostly just sat in front of his computer in his suburban home — not exactly a memorably unusual lifestyle in this modern world of ours. In the context of his author’s notes at least, the purchase of some extra memory for his computer or the switch to a new word processor counted as major life events for him.

And yet his fans absolutely ate it up. Most of them were still at an age when books and other creative works seemed to fall out of the sky fully-formed from a realm completely isolated from their own experience. Their glimpses of a real person behind the curtain of the Xanth novels marked for many of them their first exposure to the idea of artistic creation as a human labor — perhaps one they could even engage in themselves. And so, far from being a disadvantage, this sweeping away of the creative mystique was a big part of Xanth’s appeal, inculcating enormous loyalty in Anthony’s young readers. A memorable 2012 episode of the radio show This American Life illustrates the real bond that existed (and presumably still exists) between Anthony and his fans by telling the story of a picked-on teenage boy who ran away to the house of his favorite author — and was, it must be said, treated by said author with great kindness and compassion when he arrived there.

Yet even as he was nurturing such a warm relationship with his fans, Anthony was cementing his reputation among his peers as one of the biggest jerks in genre publishing. His career has been a long string of feuds and shattered friendships, which he describes at length in his autobiographies. His most longstanding battle has been with the Science Fiction Writers of America, an organization he claims to have “blacklisted” him during his lean years; no one actually involved with the SFWA is quite sure what he’s talking about. The real core of Anthony’s anger would seem to be his frustration at not being taken seriously by such establishment organs as this one. He’s long since been dismissed — admittedly, on pretty good evidence — as a hack; there will be no more Hugo talk in his future. Anthony complains endlessly about how all of his more “adult” fiction has been overshadowed by the Xanth novels which have made him a rich man, but has never taken the obvious step of simply not writing any more of the latter. The tension between artistic and commercial demands has tortured the psyche of many a writer, but in Anthony’s case it feels more comical than tragic, given that his adult books all tend to read like Xanth novels with more explicit violence — and, most especially, with much more explicit sex. And so we arrive at the really disturbing side of Piers Anthony.

I want to be especially careful in what I say next because I’ve always tried to separate the creator from his work when writing criticism of any stripe. Certainly there’s no shame in writing disposable children’s entertainment. And certainly there have been plenty of other writers who have also been jerks, including some whose talents far exceeded those of Anthony. And certainly writers need to be able to address difficult, uncomfortable subject matter without being accused of promoting or glorifying the things they describe; Vladimir Nabokov should not be deemed a pedophile because he wrote Lolita. But, even having taken all of that to heart, it remains hard for me to avoid the feeling when reading Piers Anthony on the subject of sex that something is simply wrong with this guy.

Anthony’s wrongness about sex, I should emphasize, isn’t the usual science-fiction author’s clunky mawkishness. It’s more extreme even than Robert A. Heinlein during his Dirty Old Man phase, when he wrote about sex like an alien with no understanding of human psychology might, describing it like any other mechanical process might be described by any of the dozens of stock Competent Men who populated his novels: “Now, you see, Friday, it’s just a matter of inserting Tab A here into Slot B, then moving it in and out like so.” No, Anthony’s obsession with girls just past the age of puberty — or in some eye-opening cases with girls who have not yet reached puberty — is more pernicious than this sort of rank cluelessness. It’s the reason that, if I saw a youngster I was fond of reading an Anthony novel, I wouldn’t just shrug my shoulders, but would actively try to steer her toward something I consider more healthy. For there really is, I think, a sickness — moral if not psychological in the clinical sense — running through this man’s body of work.

This side of Anthony isn’t new, although it has grown more pronounced over time as he’s become less beholden to editors. A Spell for Chameleon‘s gender politics weren’t particularly progressive even by the standards of the late 1970s. Its hero is a young man named Bink who wants something which his author considers to be impossible under normal circumstances: a girl with whom he can enjoy a warm friendship-of-intellectual-equals and whom he also finds sexually attractive — for it’s taken as a given by Anthony that a smart girl can never be a sexy one. The solution to Bink’s problem arrives in a girl with the unsubtle name of Chameleon, who cycles over the course of a month between a hideous but brilliant hag and a beautiful but moronic nymphomaniac. (Yes, Anthony’s idea of allegory really is that banal.) And so Bink’s problem is solved. The solution comes complete with a bit of teenage philosophizing, which Bink delivers to Chameleon’s nympho-bimbo incarnation just before they go at it again.

“I like beautiful girls,” he said. “And I like smart girls. But I don’t trust the combination. I’d settle for an ordinary girl, except she’d get dull after a while. Sometimes I want to talk with someone intelligent, and sometimes I want to –” He broke off. Her mind was like that of a child; it wasn’t really right to impose such concepts on her.

“That’s the point,” he said. “I like variety. I would have trouble living with a stupid girl all the time — but you aren’t stupid all the time. Ugliness is no good for all the time — but you aren’t ugly all the time either. You are — variety. And that is what I crave for the long-term relationship — and what no other girl can provide.”

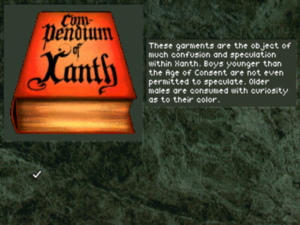

Cringe-inducingly adolescent though this take on guys and chicks might be — especially when one considers that it was written without any apparent irony by a 43-year-old man — it’s pretty harmless compared to where the Xanth novels went later on. Uncomfortably young girls get put in sexually charged situations, often with much older men, over and over. There’s little to no explicit sex — note where Bink “breaks off” in the extract above — but the subtext keeps getting more and more creepy. By 1992, Anthony felt free to entitle one of his Xanth novels The Color of Her Panties. At this point, it was hard to avoid the feeling that he was deliberately trolling the critics who had by now been calling him out for his books’ pervy subtexts for quite some time.

Still, Anthony’s allegedly prurient interest in his young female subjects would be much more speculative — and I would probably not be writing this article — were it not for those other, “adult” books of his. Many of these ooze the same disturbing fixations as the Xanth books, but are able to carry them through to, shall we say, consumation. Exhibit Number One in this category must be Firefly, a 1990 attempt at horror dealing primarily with what Anthony himself describes as “inflamed and perverted sexual desire.” It includes a lengthy sex scene between an adult man and a five-year-old girl, described in minute detail. In fact, the scene is another, rather horrifying example of Anthony’s habit of outsourcing the writing of his books: it came from an imprisoned pedophile with whom he corresponded. Anthony, in other words, literally published child porn. It’s quite simply the most disturbing thing I’ve ever read in a lifetime of prolific reading. Not even Mein Kampf bothers me like this. Needless to say, I won’t be quoting it here.

But, you counter, this was a horror novel, a genre meant to shock and transgress norms. Don’t confuse the author with the work, etc. And I might reluctantly agree with you, even if I didn’t have any personal desire to ever read anything by this writer again. But then comes the author’s note, in which Anthony justifies the rape of this five-old-girl because… she wanted it. She was asking for it, tempting the man who had sex with her into the deed. (Did I mention that she is five years old?) Her name is Nymph. (Did I mention that Anthony isn’t subtle?)

There seems to be a broad spectrum of human desire, and what we call normal is only the central component. It may be that the problem is not with what is deviant, but with our definitions. I suggest in the novel that little Nymph was abused not by the man with whom she had sex, but by members of her family who warped her taste, and by the society that preferred to condemn her lover rather than address the source of the problem in her family.

Those who feel that [the imprisoned pedophile’s] stories represent abnormal taste should read My Secret Garden by Nancy Friday, which details some of the sexual fantasies of women. Neither is Nymph an invention; similar cases are all too frequent. These aspects were from my research rather than my imagination. I don’t know what is right and what is wrong; I merely hope to raise some social questions along with the entertainment provided in the novel. I suspect our priorities are confused. We have problems enough with world hunger and injustice, without making more by punishing people for deviant but perhaps harmless behavior.

Here we have it from the horse’s mouth. The rape of a five-year-old girl is “perhaps harmless.”

We often see this pattern of argument — the “hey, I’m just asking questions!” pattern — among those who wish to say something much of the society around them will consider reprehensible but who lack the courage to stand right up and do so. (You see it constantly, for example, in the toxic arena that is present-day American politics.) Added to all of the other circumstantial evidence swirling around Piers Anthony — his many almost-as provocative statements made in interviews; his correspondences with multiple imprisoned pedophiles, not just this one; the unending fascination with pubescent and prepubescent girls running through most of his novels — it raises a strong feeling that something is indeed wrong inside this fellow’s head. I should emphasize that I have no reason to believe that Anthony has ever acted on the urges in question, if they do in fact exist. Has he found a way to satisfy them through his writing instead? That would be a good thing, if so; the crime exists not in the unfortunate psychological kink of being a pedophile, but in acting upon it. Or, that is, it would be a good thing — if only his books weren’t being read.

Once you’ve seen these things, you can never unsee them. Anthony’s cherished relationships with his young fans — and again, I have no reason to believe he has ever abused their trust in any physical sense — takes on a new, creepy flavor. Suddenly all those long letters to the paralyzed girl, as collected in the book Letters to Jenny, begin to read disturbingly like… well, like he’s flirting with her. And suddenly we breathe a sigh of relief that the teenage runaway whose story was chronicled on This American Life was a boy rather than a girl. How much of this is real and how much is projection? It’s impossible to say. (Hey, I’m just asking questions…) I will say only this: please, read someone else’s books, and try to get your children to do so as well. I smell something rotten at the core of this writer’s output, and I know I’m not alone.

All of the foregoing ruminations were prompted by my ostensible “real” subject for today, the 1993 Legend Entertainment game Companions of Xanth. Ironically, I find myself with somewhat less to say about that subject than I do about Piers Anthony’s odd and disturbing career arc as a writer. The game is… reasonably good, actually, if hardly one of the most memorable works in the history of adventure gaming. The creepiness factor is kept surprisingly low under the circumstances, the humor is hit-and-miss but always good-natured, and the design, with one glaring exception which we’ll get to momentarily, is up to Legend’s usual high standard. Further, in one sense at least, the game represents a real landmark in Legend’s history: it marks the point where they finally dumped their parser and embraced the point-and-click paradigm, thus ushering in the second of the three broad phases of the company’s history and ushering out the age of the commercial text adventure writ large.

Companions of Xanth came to exist at all entirely thanks to Legend’s everyday composer and music programmer Michael Lindner, who also happened to be one of those rare readers who defy the usual age-circumscribed window of Xanth fandom; he had retained his affection for the series right into his adult years. He had first supplemented his usual duties at Legend with those of a writer and designer on 1992’s Gateway, a project consciously engineered by the company’s co-founder Bob Bates to serve as a sort of boot camp for training up new designers. Having duly completed that apprenticeship, Lindner begged for permission to make a Xanth game as his first project as a head designer. His managers obligingly made inquiries, and soon brought home a contract to make a game version of Piers Anthony’s latest Xanth novel-in-progress, which was to be titled Demons Don’t Dream. As was more usual than not for licensed projects like this, Lindner had very little direct contact with Anthony in the course of making the game. He largely had to content himself with pre-release proofs of the novel in question, whose plot the game he made follows fairly closely but not slavishly.

We can probably feel pleased for Anthony’s lack of involvement, in that it means that most of the pervier elements of Xanth are missing. While Anthony in his novel dwells at length over the “luscious young women” in the story, Lindner lays it on considerably less thickly.

The pervy aspects of Xanth aren’t overly prevalent in the game, but aren’t entirely absent either. You can look up “panties” in the in-game encyclopedia…

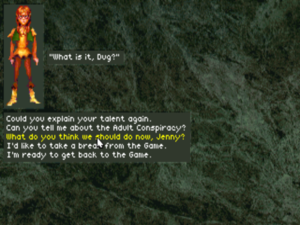

Still, the plot is rife with other Xanthian staples — not least the meta-fictional elements that had become such a hallmark of the series by this point, sixteen books in. Many of the jokes, situations, and characters in both the book and the game come courtesy of Anthony’s army of fans, who are scrupulously credited by name in the book’s author’s note. The most notable example of fan service is the character of Jenny Elf, based on the author’s young friend Jenny, the car-crash victim he wrote to at such length. (By this point, Anthony tells us in his author’s note, she had recovered from her paralysis sufficient to sit and even stand briefly without support. She would make further strides in the years to come, although she would never regain her full range of motion.) Jenny Elf, who is blessedly not overly sexualized even in the book, appears alongside Sammy Cat, the real girl’s favorite pet.

You yourself play as a teenage boy named Dug who lives in Mundania, the non-magical alternative to Xanth; Mundania, that is to say, is our world. As a hater of computer games, Dug has made a bet with his friend Ed that he won’t like one called Companions of Xanth. If his faith in the pointlessness of the gaming hobby holds true, he wins Ed’s motorcycle; if this game proves an exception to the rule, Ed gets a date with Dug’s estranged girlfriend. (“But what if she doesn’t want to go out with you?” asks Dug. “That’s a technicality we’ll deal with at the appropriate time,” answers Ed. Okay, the game isn’t totally without creepy elements…)

So, the earliest stages of the real Companions of Xanth require you to open this virtual Companions of Xanth and boot it up on your in-game computer. (Confused yet?) After some preliminaries, you get sucked through the monitor screen into Xanth. (That is to say, your character in the game you’re playing gets sucked through the monitor of the computer running the game he’s playing.)

Companions of Xanth resoundingly fails to put its best foot forward. Just as you’re about to enter Xanth and get started properly, it lives up to its name by asking you to choose a companion for your adventures from four possibilities. A nice little addition, this, you think to yourself, as you choose the companion that looks most interesting and entertaining. This must be a way to make the game replayable, a la Maniac Mansion. But nope! Think again! There’s just one “correct” companion to be chosen. Naturally, this being a Piers Anthony creation, that companion is the nubile serpent chick named Naga. If you make the supremely non-Xanthian move of choosing any of the others, the game lets you play for a few minutes longer, then dead-ends you; it’s time to restart or restore, my friend.

Such a colossal design fail is downright bizarre to see in a Legend game of this vintage. It struck me immediately that it must be an artifact of an earlier, more ambitious plan to offer four genuinely divergent experiences — a plan which got chopped down to size once the realities of time, labor, and money came home to roost. Unfortunately, neither Bob Bates nor Mike Verdu can recall what might have gone down here, and I haven’t been able to locate Michael Lindner. So, all we can do is speculate.

After a beginning like that, whatever the reason for its existence, one goes into the rest of Companions of Xanth decidedly nervous, wondering if it’s going to be one of those sorts of games. Thankfully, it isn’t; the aforementioned is its only real design pratfall. After it gets going properly, it evinces the meticulous commitment to fair play which the Legend brand was coming to stand for by 1993.

Much of the humor, and with it many of the puzzles, revolve around puns and wordplay, long a Xanth staple. Mind you, Companions of Xanth isn’t as clever as something like Infocom’s Nord and Bert Couldn’t Make Head or Tail of It in this respect. It is, after all, implicitly written for a less sophisticated audience, yet it can still be good fun in its own right. You’ll spend time here battling a censor ship, finding a way to get beyond the pail, and visiting the Fairy Nuff. Sometimes the puns go a little too far out on a limb — the “com-pewter,” an interactive compendium made out of pewter, is one example — but the puzzles themselves are always comprehensible, which is the most important thing. Only those who struggle a bit with idiomatic English in general, such as non-native speakers, are likely to have any major problems solving the game.

Companions of Xanth as a whole is as lightweight as the novels which inspired it. If it never quite dazzles, it never annoys overmuch either, at least once you get past that first hump, and it might even prompt a chuckle or two. It’s a sort of baseline standard game for Legend, never really managing to distinguish itself in either a positive or a negative way. Yet its interface did mark it as something truly new for the four-year-old company at the time of its release, and as such is perhaps worthy of more attention than the game it supports.

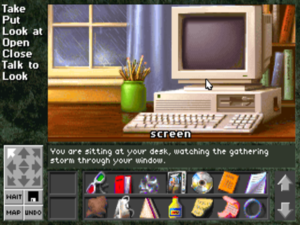

As I noted in my last article, in reality the parser disappeared more gradually than suddenly from Legend games; the full run of titles the company released between 1990 and 1993 shows a slow marginalization of the parser, until finally, beginning with Companions of Xanth, it just wasn’t there at all anymore. In fact, this same evolutionary process could be said not to have really ended even here. Although the move to point-and-click has forced the loss of that sense of infinite possibility that so delights people like me and Bob Bates, what remains here is about as text-adventure-like an interface as can be imagined under the new paradigm. Indeed, it smacks of the old ICOM Simulations interface from the mid-1980s, the industry’s earliest serious attempt to recast the classic adventure game in this mold, more so than it does the contemporary interfaces of Sierra and LucasArts. In a sense, one might even say, the parser still exists in this game. It’s just that you now build your imperative sentences with the mouse instead of the keyboard. Such an approach had always been an option in the earlier Legend games; now, it merely becomes a requirement.

Given that the screenshots of the interface included with this article are all but self-explanatory, I won’t dwell too long on its mechanics. Clicking a hotspot in the onscreen picture will highlight a default verb in the list on the left of the screen. Simply clicking on the hotspot again at this point will take that action, but you can also choose another verb from the list, if you wish. Many objects also have unique verbs which show up below the standard list when they’re highlighted; a rock, for example, might have an additional “throw” verb. And indirect objects are connected to certain actions; throwing the rock will require a third click, specifying what to throw it at. As you’re doing all of this, you see your command being built right there on the screen, just as if you were typing it in via a parser. It’s even possible to specify a verb first, then choose the object it acts upon, although this approach is of limited utility in that it doesn’t give you access to the special verbs connected to some objects.

All of which is to say that the new interface truly does represent another evolutionary rather than revolutionary technological step for Legend. What we have here is not a whole new game engine, bur rather the old one with a different front end. Once it gets past the stage of interpreting the player’s command, there’s less difference than you might expect between this Legend game and those that came before it.

This fact is most clearly illustrated in the screenshots by that little “Undo” button in the corner, something you would never — could never — see in a Sierra or LucasArts game. For those games run in real time, while Companions of Xanth, like a text adventure or an ICOM game, is still turn-based. This distinction has an enormous impact on the character of the game, reaching far beyond the welcome ability to instantly undo your last action when you get yourself killed or otherwise try something unfortunate. Legend games even after the parser went away have a more relaxed, contemplative, literary sensibility than the works of Legend’s peers. There’s still quite a lot of text here, and that text is still treated with unusual care and respect. It isn’t hard to divine, after playing around with one of their point-and-click games for just a few minutes, why Legend became the go-to studio for literary adaptations during the 1990s. While it had proved possible to take the type-in parser out of Legend’s engine, it was more difficult to take the literary spirit of the text adventure out of the company’s collective design aesthetic.

This held true even when Legend was otherwise embracing the multimedia era with gusto. Although Eric the Unready and Gateway 2: Homeworld had both been released in CD-ROM versions prior to Companions of Xanth, those were mere repackagings of the floppy-disk-based versions into a more convenient format. But when the subject of this article appeared on CD-ROM about six months after its original floppy-based release, it sported voice acting for the first time in a Legend title. And yet even here the voice acting only covered words said by the characters you met; there was no global narrator. Such an approach felt very much in keeping with that overarching literary sensibility that so marked Legend’s work. In this game, and in the next several Legend games to come, you were still expected to do a lot of reading for yourself.

For the record, the voice acting that is to be found in the CD-ROM Companions of Xanth is excellent — an impressive feat considering that this was Legend’s first foray into such a thing. Even here, their first time out, they were wise enough to employ professional actors recruited from the local union for same and recorded at a professional sound studio. It’s obvious that the actors had fun with their roles; my favorite part of the whole game might just be the blooper reel of outtakes which plays over the closing credits.

In the end, though, I find myself torn on the subject of Companions of Xanth in a way I can’t recall being for any other game I’ve written about here. If it existed in a vacuum, shorn of its association with Piers Anthony, I would call it a fun, frothy little fantasy romp, a solid debut for a new interface which retains more of the spirit of the old than we might have dared to hope for. And I would be happy enough to leave it at that. But, even as I believe it’s wrong to judge art on external factors in the vast majority of cases, there are exceptions, and I’m not sure this isn’t one of them.

I don’t blame Legend in any sense for making this game. Many of the more worrisome aspects of Anthony’s oeuvre become obvious only in the aggregate; most or all of those who worked on this game at Legend doubtless believed that they were merely capitalizing on a popular, harmless series of lightweight fantasy books. And yet I do find myself wishing that they had chosen some other series, just as I wish any current readers of Xanth, young or old, would do likewise. In my role of critic, I can tell you that Companions of Xanth is a (mostly) well-constructed game that’s relatively inoffensive in itself. But should you play it? That is, as always — but perhaps here even more so than usual — something you’ll have to decide for yourself.

(Sources: the Piers Anthony books Bio of an Ogre, How Precious was that While, Letters to Jenny, Macroscope, A Spell for Chameleon, The Color of Her Panties, Firefly, and Demons Don’t Dream; Computer Gaming World of July 1993 and March 1994; Questbusters 108. My thanks go to Bob Bates and Mike Verdu for talking with me about this period of Legend’s history — but I must emphatically state that all of the opinions expressed herein, especially of Piers Anthony and his work, are mine alone.

Companions of Xanth has not been re-released as a digital edition, doubtless owing to the complications involved with licensed titles. I’d prefer not to host it here due to my distaste for Piers Anthony, but you can find it elsewhere without too much trouble.)

BONUS:

The Compiled Life Wisdom of Piers Anthony, as Found in His Autobiographies

Writers like Roger Zelazny and Samuel Delany got awards because of their sophistication as writers, which sophistication I do not question, but I was regarded from the outset as an entertainment writer. What I was doing was too complex and subtle, not only for others to understand, but for them even to realize that it existed.

The best guide for a book to avoid is an award winner.

I worried that I would not be able to write fantasy well without Lester del Rey’s editing. But instead it was like a burden lifting from my shoulders. Suddenly I was free of oppressive editing.

Then Lester tried to cut the entire Author’s Note from the fourth Incarnations novel, Wielding a Red Sword. He said it was too long, and anyway, they were in the business of publishing fiction, not nonfiction. This was the Note in which I described my computerization — I had until then written my novels in pencil and then typed them with a manual machine, so it was a significant step for me.

When I read Isaac Asimov’s massive two-volume autobiography I found it interesting, but concluded that the minutia of daily existence are seldom worth recording for posterity.

I dumped SFWA, and have remained hostile to it since. There is evidence that some of its members are still spreading falsehoods about me. If ever push comes to shove, I will put it out of business. Because today I have the resources to sue. All I need is the pretext.

I, like most boys, would have been capable of orgasm at any time in childhood, had I known how to masturbate.

A formula I invented for explaining the ways of publishers: TPB = SOD. What does it mean? Typical Publisher Behavior is Shitting On Dreams.

So are publishers really as rapacious and idiotic as they seem? Yes and no. Just as the intelligence and conscience of a lynch mob may be less than that of any individual person within it, so may the net savvy of a publisher be below that of any of its components.

I feel like a beautiful woman. That is, a lovely woman is pursued by many men — but when she mentions commitment, most of them vanish. Some vanish when they find they can’t get her into bed on the first date. Others vanish after they do get her into bed. So she becomes cynical; it is evident that most of those ardent suitors are insincere; all they want is her body for a night, rather than an enduring relationship, unless she happens to be rich. All the publishers really wanted from me was my best-selling series, Xanth — and those who lost it and those who got it tended to vanish as far as my other novels went.

I pondered, and my agent pondered, and it was my wife, who evidently understands the situation of beautiful women, who came up with an effective notion: link the one to the other. Make a package deal. So when the time for a new multi-novel Xanth contract came up, we put it to TOR: double or nothing. If this man wanted to get this woman in bed again, there would have to be marriage — though TOR’s chief editor is female, and I’m male.

[My wife and I] have what I call a conventional marriage: I earn the money, she spends it. In fact she keeps accounts and does the taxes, which are complicated. I decide on the big things, like the significance of world events, and she decides the small things, like everything else. I’m glad I married her, and believe that I would not be where I am today without her. But if I should find myself alone, I would then consider more carefully what else offers, with strong cautions from my life experience. Meanwhile I have a small category of correspondents I treat politely: those who profess or imply love for me.

Women of any age are interesting, and as a general rule, the younger a woman is, the more interesting she is, because natural selection dictates that the man who controls the greatest part of a woman’s fertile years will have the most children. A girl of twelve may have breasts and be a young woman in appearance; she is sexually desirable, regardless of law or custom. A girl of eleven may lack the breasts but be of similar general appearance, and her clothing masks her lack of maturity. So it is evident that some men aren’t concerned about the distinction, and go for the vagina regardless.

I have an insatiable curiosity about the nature of the universe and mankind’s place in it, and my profession of writing allows me to explore it all, seeking answers. I have fathomed a number of things to my satisfaction before they were clarified by the scientists.

Sometimes I’m stupid. This is annoying when I’m taking an IQ test.