This is what a revolutionary technology looks like. In very early 1986 Tim Jenison, founder of NewTek, began distributing these full-color digitized photographs, the first of their kind ever to be seen on a PC screen, to Amiga public-domain software exchanges. The age of multimedia computing had arrived.

The Amiga was the damnedest computer. A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, then all crammed into a plastic case; that was the Amiga. I wrote a book about the thing, and I’m still not sure I can make sense of all of its complications and contradictions.

The Amiga was a great computer when it made its debut in 1985, better by far than anything else on the market. At its heart was the wonderchip of the era, the Motorola 68000, the same CPU found in the Apple Macintosh and the Atari ST. But what made the Amiga special was the stuff found around the 68000: three custom chips with the unforgettable names of Paula, Denise, and Agnus. Together they gave the Amiga the best graphics and sound in the industry by a veritable order of magnitude. And by relieving the 68000 of a huge chunk of the burden for generating graphics and sound as well as performing many other tasks, such as disk access, they let the Amiga dazzle while also running rings around the competition in real-world performance by virtually any test you cared to name. It all added up not just to incremental improvement but rather to that rarest thing in any field of endeavor: a generational leap.

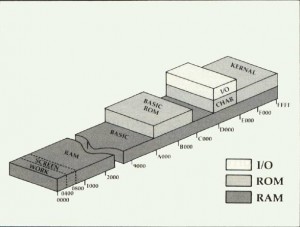

The Amiga, especially in its original 1985 incarnation, was a terrible computer. The operating system that shipped with it was painfully buggy. If you could manage to use the machine for just an hour or two without it inexplicably running out of memory and crashing you were doing well. Other glitches were bizarrely entertaining if they didn’t happen to you personally, such as the mysterious “date virus” that could start to spread through all your disks, setting the timestamp on every file to sometime in the year 65,000 and slowing the system to a crawl. (No, this “virus” wasn’t actual malware, just a weird bug.) Of course, software could be and to a large extent eventually was fixed. Other problems were more intractable. There was, for instance, the machine’s use of interlaced video for its higher resolution modes, which caused those marvelous graphics to flicker horribly in most color combinations. Baffled users who felt like their swollen eyeballs were about to pop right out of their heads after a few hours of trying to work like this could expect to be greeted with a lot of technical explanations of why it was happening and suggestions for changing their onscreen color palettes to try to minimize it. Certainly anyone who picked up an Amiga expecting an experience similar to the famously easy-to-use Macintosh was in for a disappointment. Despite the Amiga’s sporting a superficially similar mouse-and-windows interface, users hoping to get serious work or play done on the Amiga would need to educate themselves on such technical minutiae as the difference between “chip” and “fast” memory and learn what a program’s “stack” was and how to set it manually. Even on a good day the Amiga always felt like a house of cards ready to be blown over by the first breath of wind. When the breeze came, the user was left staring at an inscrutable “Guru Meditation Error” and a bunch of intimidating numbers. Sometimes the Amiga could seem positively designed to confound.

The Amiga anticipated the future, marked the beginning of a new era. It pointed forward to the way we live and compute today. I titled my book on the machine The Future Was Here for a reason. That aforementioned generational leap in graphics and sound was the most significant in the history of the personal computer in that it made the Amiga not just a new computer but something qualitatively new under the sun: the world’s first multimedia PC. With an Amiga you could for the first time store and play back in an aesthetically pleasing way imagery and sound captured from the real world, and combine and manipulate and interact with it within the digital environment inside the computer. This changed everything about the way we compute, the way we play, and eventually the way we live, making possible everything from the World Wide Web to the iPod, iPad, and iPhone. Almost as significantly, the Amiga pioneered multitasking on a PC, another feature enabled largely by that magnificent hardware that was able to stretch the 68000 so much farther than other computers. There is considerable psychological research today that indicates that, for better or for worse, multitasking has literally changed the way we think, changed our brains — not a bad claim to fame for any commercial gadget. When you listen to music whilst Skyping on-and-off with a friend whilst trying to get that term paper finished whilst looking for a new pair of shoes on Amazon, you are what the Amiga wrought.

The Amiga was stuck in the past way of doing things, thus marking the end of an era as well as the beginning of one. It was the punctuation mark at the end of the wild-and-wooly first decade of the American PC, the last time an American company would dare to release a brand new machine that was completely incompatible with what had come before. Its hardware design reflected the past as much as the future. Those custom chips, coupled together and to the 68000 so tightly that not a cycle was wasted, were a beautiful piece of high-wire engineering created by a bare handful of brilliant individuals. If a computer can be a work of art, the Amiga certainly qualified. Yet its design was also an evolutionary dead end; the custom chips and all the rest were all but impossible to pull apart and improve without breaking all of the software that had come before. The future would lie with modular, expandable design frameworks like those employed by the IBM PC and its clones, open hardware (and software) standards that were nowhere near as sexy or as elegant but that could grow and improve with time.

The Amiga was a great success, the last such before the Wintel hegemony expanded to dominate home computing like it already did business by the mid-1980s. Its gaming legacy is amongst the richest of any platform ever, including some fifteen years worth of titles that, especially during the first half of that period, broke boundaries at every turn and expanded the very notion of what a computer game could be. I won’t even begin to list here the groundbreaking classics that were born on the Amiga; suffice to say that they’ll be featuring in this blog for years to come. The Amiga was so popular a gaming platform in Europe that it survived many years after the death of its corporate parent Commodore, a phenomenon unprecedented in consumer computing. The last of the many glossy newsstand magazines devoted to it, Britain’s Amiga Active, didn’t cease publication until November of 2001, well over seven years after the platform became an orphan. It would prove to be just as long-lived in its other major niche of video-production workstation. Thanks to their unique ability to blend their own visuals with analog video signals — enabled, ironically, by those very same interlaced video modes that drove so many users crazy — Amigas could be found in the back rooms of small cable stations and video producers into the 2000s. Only the great changeover to digital HD broadcasting finally and definitively put an end to the Amiga’s career in this realm.

The Amiga was a bitter failure, one of the great might-have-beens of computer history. In 1985 so many expected it to become so much more than just another game machine or even “just” the pioneer of the whole new field of desktop video, forerunner of the YouTube generation. The Amiga, believed its early adopters, was so much better — not just technically better but conceptually better — than what was already out there that it was surely destined to conquer the world. After all, business-software heavy hitters like WordPerfect, Borland, Ashton-Tate, and Lotus knew a good thing when they saw it, were already porting their applications to it. And yet in the end only WordPerfect came through, for a while, and, while the Amiga did change the world in the long term, its innovations were refined and made into everyday life by Apple and Microsoft rather than the Amiga itself. The vast majority of heirs to the Amiga’s legacy today — a number which includes virtually every citizen of the developed world — have no idea a computer called the Amiga ever existed.

That’s just a sample of the contradictions awaiting any writer who tries to seriously tackle the Amiga as a subject. And there’s also another, more ironic sort of difficulty to be confronted: the sheer love the Amiga generated on the part of so many who had one. The Amiga, I must confess, was my own first computing love. Since that day in 1994 when I gave in and bought my first Wintel machine, I’ve been platform-agnostic. Linux and Apple zealots and Microsoft apologists all leave me cold, leave me wondering how people can get so passionate about any platform not called Amiga. Of course I’m smart enough to realize that none of this is really all that important, that a gadget is just that, a means to an end. I even recognize that, had the Amiga not come along when it did to pioneer a new paradigm for computing, something else would have. That’s just how history works. But still, there was something special about the Amiga for those of us who were there, something going far beyond even a hacker’s typical love for his first computer.

To say Amiga users had — still have — a reputation for zealotry hardly begins to state the case. General-computing magazines from the late 1980s until well into the 1990s learned to expect a deluge of hate mail from Amiga users every time they published an article that dared say an unfavorable word about the platform — or, worse, and as inevitably happened more and more frequently as time went on and the Amiga faded further from prominence, that didn’t mention it at all. Prominent mainstream columnist John C. Dvorak liked to say that, whereas Mac users were just arrogant and self-righteous, Amiga users were actively delusional. There are still folks out there clinging to their 25-year-old Amigas, patched together with the proverbial duct tape and baling wire, as their primary computing platform. A disturbing number of them are still waiting for the day when the Amiga shall rise again and take over the world, even as it’s hard to understand what a modern Amiga should even be or why it should exist in a world that long since incorporated all of the platform’s best ideas into slicker, simpler gadgets.

Every good cult needs an origin myth, and the Cult of Amiga is no exception. Beginning already in the machine’s North American heyday of the late 1980s, High Priest R.J. Mical, developer of the Amiga’s Intuition library of GUI widgets as well as other critical pieces of its software infrastructure, began traveling to trade shows and conventions telling in an unabashedly sentimental way the story of those earliest days, when the Amiga was being developed by a tiny independent company, itself called simply Amiga, Incorporated.

We were trying to find people that had fire, that had spirit, that had a dream they were trying to accomplish. Carl Sassenrath, the guy that did the Exec for the machine, it was his lifelong dream to do a multitasking operating system that would be a work of art, that would be a thing of beauty. Dale Luck, the guy that did the graphics, this was his undying dream since he was in college to do this incredible graphics stuff.

We were looking for people with that kind of passion, that kind of spirit. More than anything else, the thing that we were looking for was people who were trying to make a mark on the world, not just in the industry but on the world in general. We were looking for people that really wanted to make a statement, that really wanted to do an incredibly great thing, not just someone who was looking for a job.

Yes. Well. While idealism certainly has its place in the Amiga story, the story is also a very down-to-earth tale of competition inside Silicon Valley. It begins in 1982 with an old friend of ours: Larry Kaplan, one of the Fantastic Four game programmers from Atari who founded Activision along with Jim Levy.

Activison was flying high in 1982, the Fantastic Four provided in Kaplan’s own words with “limousine service, company cars, and a private chef” on top of a base salary of $150,000. Yet Kaplan, who is often described by others as the very apotheosis of “the grass is always greener,” was restless. He had the idea to form another company, one all his own this time, to enter the booming Atari VCS market. One day in early 1982 he called up an old colleague of his from the Atari days: Jay Miner, who had designed the Atari VCS’s display chip, then gone on to design the chipset at the heart of the Atari 400 and 800 home computers. Kaplan, along with two others of the Fantastic Four, had written the operating system and BASIC language implementation for those machines. He thus knew Miner well. Knowing the vagaries of business and starting his own company somewhat less well than he knew Miner and programming, his initial query was a simple one: “I’d like to start a company. Do you know any lawyers?”

Miner, who had left Atari at around the same time as the Fantastic Four out of a similar disgust with new CEO Ray Kassar, had also left Silicon Valley to move to Freeport, Texas, where he worked for a small semiconductor company called Zymos, designing chips for pacemakers and other medical devices. Miner said that, no, he wasn’t particularly well-acquainted with any lawyers, good or otherwise, but that his boss, Zymos founder Bert Braddock, had a pretty good head for business. He made the introduction, and Kaplan and Braddock hit it off. The plan that Kaplan presented to him was to combine hardware and software in the booming home videogame space, offering hardware to improve on the Atari VCS’s decidedly limited capabilities along with game cartridges that took advantage of the additional gadgetry. Such a scheme was hardly original to him; confronted with the VCS’s enormous popularity and equally enormous limitations, others were already working the same space. For example, two other former Atari engineers, Bob Brown and Craig Nelson, had already formed Starpath to develop a “Supercharger” hardware expansion for the VCS as well as games to play with it. (Starpath would go on to merge with the newly renamed Epyx — née Automated Simulations — and write games like Summer Games.)

Nevertheless, Braddock sensed a potentially fruitful partnership in the offing for a maker of chips like his Zymos. He found Kaplan some investors in nearby oil-rich Houston to put up the first $1 million or so to get the company off the ground. He also found and recruited one Dave Morse, a vice president of marketing at Tonka Toys, to join Kaplan, believing him to be exactly the savvy business mind and shrewd negotiator the venture needed. An informal agreement was reached amongst the group: Morse would run the new company; Kaplan would write the games; Miner (working under contract, being still employed by Zymos) would design the ancillary hardware; and Zymos would manufacture the hardware and the game cartridges. Somewhere at the back of everyone’s mind was the idea that, if they were successful with their games and add-on gadgets, they might just be able to take the next step: to make a complete original game console of their own, the successor to the Atari VCS that Ray Kassar’s Atari didn’t seem all that interested in seriously pursuing.

In June of 1982, Kaplan announced to his shocked colleagues at Activision that he was moving on to do his own thing; the bridges he thus burnt have never been mended to this day. He and Morse opened a small office in Santa Clara, California, for their new company, which Kaplan named Hi-Toro. Morse and Braddock — truly a sugar daddy to die for for a fledgling corporation — beat the bushes over the months that followed for additional financing, with success to the tune of another $5 million or so. The majority were dentists and other members of the medical establishment, thanks to Braddock’s connections in that field. They knew little to nothing about computer technology, but knew very well that videogames were hot, and were eager to get in on the ground floor of another Atari.

And then the squirrely Larry Kaplan nearly undid the whole thing. He called Atari founder Nolan Bushnell that October to talk up his new company, hoping to convince him to join Hi-Toro as chairman of the board; a name like his would confer instant legitimacy. Instead the hunter became the hunted. Bushnell, who was legendary for the buckets of charm at his fingertips, convinced Kaplan to come to him, convinced him they could start a new videogame company to rival Atari together, without Zymos or Morse or Miner. Just like that, Kaplan tendered his second shocking resignation of 1982. In the end, as Kaplan later put it, “Nolan, of course, flaked out,” leaving him high and dry, if quite possibly deservedly so. He would end up completing the circle by going back to Atari before the year was up, but that gig ended when the Great Videogame Crash of 1983 hit. Widely regarded as too untrustworthy to be worth the trouble inside the industry by that point, Kaplan’s career never recovered. On the plus side, he was able to cash out his Activision stock following that company’s IPO, making him quite a wealthy man and making future work largely optional anyway — not the worst of petards for a modern-day Claudius.

Dave Morse, meanwhile, was also left high and dry, with a company and an office and lots of financing but nobody to design his products. He asked Jay Miner to leave Zymos and join him full-time at Hi-Toro, to help fill the vacuum left by Kaplan’s departure. Miner, who had been nursing for some time now a dream of doing a game console and/or a computer based around the new Motorola 68000 and who saw Hi-Toro as just possibly his one and only chance to do that, agreed — so long as he could bring his beloved cockapoo Mitchy with him to the office every day.

One of the first things to go after Kaplan left was the company name he had come up with. Everyone Morse and Miner spoke to agreed that “Hi-Toro” was a terrible name that made one think of nothing so much as lawn mowers. Morse therefore started flipping through a dictionary one day, looking for something that would come before Apple and Atari in corporate directories. He hit upon the Spanish word for “friend”: “amigo.” That had a nice ring to it, especially with “user-friendliness” being one of the buzzwords of the era. But the feminine version of the word — “amiga” — sounded even better, friendly and elegant maybe even a little bit sexy. Miner by his own later admission was ambivalent about the new name, but everyone Morse spoke to seemed very taken with it, so he let it go. Thus did Hi-Toro become Amiga.

Of course, Morse and Miner couldn’t do all the work by themselves. Over the months that followed they assembled a team whose names would go down in hacker lore. An old colleague from Atari who had worked with Miner on the VCS as well as the 400 and 800, Joe Decuir, came in under a temporary contract to help Miner start work on a new set of custom chips. A few other young hardware engineers were hired as full-time employees. Morse hired one Bob Pariseau to put together a software team; he became essentially the equivalent of Jay Miner on that side of the house. The software people would soon grow to outnumber the hardware people. Among their ranks were now-legendary Amiga names like R.J. Mical, Dale Luck, and Carl Sassenrath.

The folks who came to work at Amiga were almost universally young and largely inexperienced. While tarring them with the clichéd “dreamers and misfits” label may be going too far, it is true that their backgrounds were more diverse than the Silicon Valley norm; Mical, for instance, was a failed English major who had recently spent nine months backpacking his way around the world. While their youthful idealism would do much to give the eventual Amiga computer its character, there was also a very practical reason that Morse had to fill his office with all these bright young sparks: what with financing getting harder and harder to come by as the videogame industry began to go distinctly soft, he simply couldn’t afford to pay for more experienced hands. Amiga’s financial difficulties provided the opportunity of a lifetime to a bunch of folks that may have struggled to get in the door in even the most junior of positions at someplace like Apple, IBM, or Microsoft.

The glaring exception to the demographic rule at Amiga was Jay Miner himself. Creative, bleeding-edge engineering is normally a young person’s game. Miner, however, was fully 50 years old when he created his masterpiece, the Amiga chipset. He’d been designing circuits already twenty years before the microprocessor even existed and well before some of his colleagues around the office were even born. Thanks perhaps to intermittent but chronic kidney problems that would eventually kill him at age 62, he looked and in some ways acted even older than his years, favoring quiet, contemplative hobbies like cultivating bonsai trees and carving model airplanes out of balsa wood. Adjectives like “fatherly” rival “soft-spoken” and “wise” in popularity when people who knew him remember him today. While the higher-strung Dave Morse became the face Amiga showed to the outside world, Miner set the internal tone, tolerating and even encouraging the cheerful insanity that was life inside the Amiga offices. Miner:

The great things about working on the Amiga? Number one I was allowed to take my dog to work, and that set the tone for the whole atmosphere of the place. It was more than just companionship with Mitchy — the fact that she was there meant that the other people wouldn’t be too critical of some of those we hired, who were quite frankly weird. There were guys coming to work in purple tights and pink bunny slippers. Dale Luck looked like your average off-the-street homeless hippy with long hair and was pretty laid-back. In fact the whole group was pretty laid-back. I wasn’t about to say anything — I knew talent when I saw it and even Parasseau who spread the word was a bit weird in a lot of ways. The job gets done and that’s all that matters. I didn’t care how solutions came about even if people were working at home.

The question of just what this group was working on, and when, is a harder question to answer than you might expect. When we use the word “Amiga” to refer to this era, we could be talking about any of three possibilities. Firstly, there’s Amiga the company, which during its early months put well over half of its personnel and resources into games and add-ons for the old Atari VCS rather than revolutionary new technology. Then there’s the Amiga chipset being designed by Miner and his team. And finally there’s a completed game console and/or computer to incorporate the chipset. Making sense of this tangle is complicated by revisionist retellings, which tend to find grand plans and coherent narratives where none actually existed. So, let’s take a careful look at each of these Amigas, one at a time.

Kaplan’s original plan had envisioned Hi-Toro/Amiga as a maker first and foremost of cartridges and hardware add-ons for the VCS, with a whole new console possibly to follow if things went gangbusters. These plans got reprioritized somewhat when Kaplan left and Miner came aboard with his eagerness to do a console and/or computer, but they were by no means entirely discarded. Thus Amiga did indeed create a handful of original games over the course of 1983, along with joysticks and other hardware. By far the most innovative and best-remembered of these products was something called the Joyboard: a large, flat slab of plastic on which the player stood and leaned side to side and front to back to control a game in lieu of a joystick. Amiga packaged a skiing game, Mogul Maniac, with the Joyboard, and developed at least two more — a surfing game called Surf’s Up and a pattern-matching exercise called Off Your Rocker — that never saw release. The Joyboard and its companion products have been frequently characterized as little more than elaborate ruses designed to keep the real Amiga project under wraps. In reality, though, Morse had high commercial hopes for this side of his company; he was in fact depending on these products to fund the other side of the operation. He spent quite lavishly to give the Joyboard a splashy introduction at the New York Toy Fair in February of 1983, and briefly hired former Olympic skier Suzy Chaffee — better known to a generation of Americans as “Suzy Chapstick” thanks to her long-running endorsement of that brand — to serve as spokesperson. His plans were undone by the Great Videogame Crash. The peripherals and games all failed miserably, precipitating a financial crisis at Amiga to which I’ll return shortly.

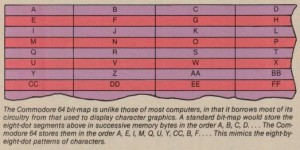

The chips were always Jay Miner’s babies. Known in the early days as Portia, Daphne, and Agnus, later iterations would see Portia renamed to Paula and Daphne to Denise. Combined with a 68000, they offered unprecedented audiovisual capabilities, including a palette of 4096 colors and four-channel stereo sound. Their most innovative features were the so-called “copper” and “blitter” housed inside Agnus. The former, which could also be found in a less advanced version in Miner’s previous Atari 400 and 800, could run short programs independent of the CPU to change the display setup on the fly in response to the perpetually repainting electron gun behind the television or monitor reaching certain points in its cycle. This opened the door to a whole universe of visual trickery. The blitter, meanwhile, could be programmed to copy blocks of memory from place to place at lightning speeds, and in the process perform transformations and combinations on the data — once again, independent of the CPU. It was a miracle worker in the realm of fast animation. While not programmable in the same sense as the copper and the blitter, Denise autonomously handled the task of actually painting the display, while Paula could autonomously play back up to four sound samples or waveforms at a time, and also independently handle input and output to disk. (This is the briefest of technical summaries of the Amiga chipset. For a detailed description of the chipset’s internal workings as well as many important aspects of its host platform’s history that I’ll never get to in this game-focused blog, I point you again to my own book on the subject.)

Amiga’s ultimate vision for their chipset — whether in the form of a game console, a computer, a standup arcade game, or all three — is the most difficult part of all their tangled skein of intentionality to unravel, and the one most subject to revisionist history. Amiga fanatics of later years, desperate to have their platform accepted as a “serious” computer like the IBM PC or Apple Macintosh, became rather ashamed of its origins in the videogame industry. This has occasionally led them to say that the Amiga was always secretly intended to be a computer, that the videogame plans were just there to fool the investors and keep the money flowing. In truth, there’s good reason to question whether there was any real long-term plan at all. Miner noted in later interviews that the company was quite split on the subject, with — ironically in light of his later status of Amiga High Priest — R.J. Mical on the “investors’ side,” pushing for a low-cost game console, while others like Dale Luck and Carl Sassenrath wanted an Amiga computer. Miner himself claimed to have envisioned a console that could be expanded into a real computer with the addition of an optional keyboard and disk drive. (Amiga also had similar plans for the Atari VCS in the form of something to be called the Amiga Power Module, yet another project killed by the videogame collapse.) Dave Morse, who died in 2007, is not on record at all on the subject. One suspects that he was simply in wait-and-see mode through much of 1983.

What is clear is that the first Amiga machine to be shown to the public wasn’t so much a prototype of a real or potential computer or game console as the most minimalist possible frame to show off the capabilities of the Amiga chipset. Named after Morse’s wife, the Amiga Lorraine began to come together in the dying days of 1983, in a mad scramble leading up to the Winter Consumer Electronics Show that was scheduled to begin on January 4. Any mad scientist would have been proud to lay claim to the contraption. Miner and his team built their chipset, destined eventually to be miniaturized and etched into silicon, out of off-the-shelf electronics components, creating a pile of breadboards large enough to fill a kitchen table, linked together by a spaghetti-like tangle of wires, often precariously held in place with simple alligator clips. It had no keyboard or other input method; the software team wrote programs for it on a workstation-class 68000-based computer called the Sage IV, then uploaded them to the Lorraine and ran them via a cabled connection. The whole mess was a nightmare to maintain, with wires constantly falling off, pieces overheating, or circuits shorting out seemingly at random. But when it worked it provided the first tangible demonstration of Miner’s extraordinary design. Amiga accordingly packed it all up and transported it — very carefully! — to Las Vegas for its coming-out party at Winter CES.

R.J. Mical and Dale Luck, amongst others, had worked feverishly to create a handful of demos to show off in a private corner of Amiga’s CES booth, open only by invitation to hand-selected members of the press and industry. The hit of the bunch, written by Mical and Luck at the show itself in one feverish all-night hacking session fueled by “a six pack of warm beer,” was a huge, checked soccer ball that bounced up and down, prototype of one of the most famous computerized demos of all time. The bouncing soccer ball — the “boing” ball — would soon become the unofficial symbol of Amiga.

Boing and the other demos were impressive, but the hardware was obviously still in a very rough state, still a long, long way away from any sort of salable product. Many observers were frankly skeptical whether this mass of breadboards and wires even could be turned into the three chips Amiga promised, and if so whether those chips could, complicated as they must inevitably be, be cost-effectively manufactured. Two obvious applications of the chipset, to a new videogame console or to standup arcade games, were facing a gale-force headwind following the Great Videogame Crash of the previous year. Nobody wanted anything to do with that market anymore. And introducing yet another incompatible computer into the market, no matter how impressive its hardware, looked like a high-risk proposition as well. Thus most visitors were impressed but carefully noncommittal. Was there really a place for Amiga’s admittedly extraordinary technology? That was the question. Tellingly, of the glossy magazines, only Creative Computing bothered to write about Lorraine in any real detail, excitedly declaring it to have “the most amazing graphics and sound that will ever have been offered in the consumer market.” (Just to show that prescience isn’t always an either/or proposition, the same journalist, John J. Anderson, noted how important it would be to make sure any eventual Amiga computer was compatible with the IBM PCjr, which was sure to take over the industry.)

Thus Amiga’s coming-out party is best characterized as having mixed results on the whole, leading to lots of impressed observers but no new investors. And that was a big, big problem because Amiga was quickly running out of money. With the VCS products having not only failed to sell but also absorbed millions in their own right to develop, Amiga’s financial picture was getting more desperate by the week. One thing was becoming clear: there was no way they were going to be able to secure the investment needed to turn the Lorraine into a completed computer — or a completed anything else — and market it themselves. It seemed that they had three options: license the technology to someone else with deeper pockets, sell themselves outright to someone else, or go quietly out of business. As the founders mortgaged their houses to make payroll and Morse begged his creditors for loan extensions, the only company that seemed seriously interested in the Amiga chipset was the one Jay Miner would least prefer to get in bed with once again: Atari.

An Atari old-timer named Mike Albaugh had first visited Amiga well before the CES show, in November of 1983. He was given an overview of the as-yet-extant-on-paper-only chipset’s features and, knowing very well the capabilities of Jay Miner, expressed cautious interest. After their first tangible glimpse of the chipset’s capabilities at CES, Atari got serious about acquiring this incredible technology from a company that seemed all but at their mercy, desperate to make a deal that would let them stay alive a little longer. With no other realistic options on the table, Dave Morse negotiated with Atari as best he could from his position of weakness. Atari had no interest in buying a completed machine, whether of the game-console or computer variety. They just wanted that wonderful chipset. The preliminary letter of intent that Amiga and Atari signed on March 7, 1984, reflects this.

That same letter of intent, and the $500,000 that Atari transferred to Amiga as part of it, would lead to a legal imbroglio lasting years. The specifics that the letter contained, as well as — equally importantly — what it did not contain, remain persistently misunderstood to this day. Thankfully, the original agreement has been preserved and made available online by Atari historians Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel. I’ve taken the time to parse this document closely, and also enlisted the aid of a couple of acquaintances with better legal and financial minds than my own. Because it’s so critical to the story of Amiga, and because it’s been so widely misunderstood and misconstrued, I think it’s worth taking a moment here to look fairly closely at its specifics.

The document outlines a proposed arrangement granting Atari exclusive license to the chipset for use in home videogame consoles and standup arcade games, in perpetuity from the time that the finalized agreement is signed. The proposal also grants Atari a nonexclusive license to use the chips in a personal computer, subject to the restriction that Atari may first offer an add-on kit to turn a game console using the chips into a full-blown computer in June of 1985, and a standalone computer using the chips only in March of 1986. Before and continuing after Atari makes their computer using the chips, Amiga may make one of their own, but may only sell it through specialized computer dealers, not mass merchandisers like Sears or Toys ‘R’ Us. Atari, conversely, will be restricted to the mass merchandisers. The obvious intention here is to target Amiga’s products to the high-end, professional market, Atari’s to gamers and casual users. Atari will pay Amiga a royalty of $2 per computer or game console containing the chipset sold, $15 per standup arcade videogame. Note that the terms I’ve just described are only a proposal pending a finalized license agreement, without legal force — unless certain things happen to automatically trigger their going into effect, which I’ll get to momentarily.

Now let’s look at the parts of the document that do have immediate legal force. Amiga being starved for cash and still needing to do considerable work to complete the chipset, Atari will give Amiga an immediate “loan” of $500,000, albeit one which they never really expect to see paid back; again, I’ll explain why momentarily. Atari will then continue to give Amiga more loans on a milestone basis: $1 million when a finalized licensing agreement is signed; $500,000 when each of the three chips is completed and delivered to Atari ready for manufacturing. And here’s where things get tricky: once all of the chips are delivered and a licensing agreement is in place, Amiga’s outstanding loan obligations will be converted into a purchase by Atari of $3 million worth of Amiga stock. If, on the other hand, a finalized licensing agreement has not been signed by March 31 — just three weeks from the date of this preliminary agreement — Amiga will be expected to pay back the $500,000 to Atari by June 30, plus interest of 120 percent of the current Bank of America prime rate, assuming some other deal is not negotiated in the interim. If Amiga cannot or will not do so, the proposed licensing agreement outlined above will automatically go into effect as a legally binding contract, with the one very significant change that Atari will not need to pay any royalties at all — the license “shall be fully paid in exchange for cancellation of the loan.” The Amiga chipset thus serves as collateral for the loan, its blueprints and technical specifications being held in escrow by a neutral third party (the Bank of America).

There are plenty of other technicalities — for instance, Atari will be allowed to bill Amiga for their time and other resources if Amiga fails to complete the chipset, thus forcing Atari’s engineers to finish the job — but I believe I’ve covered the salient points here. (Those deeply interested or skeptical of my conclusions may want to look at a more detailed summary I prepared, or, best of all, just have a look at the original.) Looking at the contract, what jumps out first is that it wasn’t a particularly good deal for Amiga. To pay a mere $2 per console or computer sold when the chipset being paid for must be the component that literally makes that console or computer what it is seems shabby indeed. For Atari it would have represented the steal of the century. Why would Morse sign such an awful deal?

The obvious answer must of course be that he was desperate. While it’s perhaps dangerous to ascribe too much motivation to a dead man who never publicly commented on the subject, circumstantial evidence would seem to characterize this agreement as the wind-up to a final Hail Mary, a way to secure a quick $500,000 for the here and now, to keep the lights on a little longer and hope for a miracle. Morse did not sign a final licensing agreement by March 31, a very risky move indeed, as it gave Atari the right to automatically start using Amiga’s chipset, without having to pay Amiga another cent, if Morse couldn’t negotiate some other arrangement with them or find some way to pay back the $500,000 plus interest before June 30. Carl Sassenrath once described Morse as “my model for how to be cool in business.” Truly he must have had nerves of steel. And, incredibly, he would get his miracle.

(Sources: On the Edge by Brian Bagnall. Amiga User International of June 1988 and March 1993. Info of January/February 1987 and July/August 1988. Creative Computing of April 1984. Amazing Computing, premiere issue. InfoWorld of July 12 1982. Commander of August 1983. Scott Stilphen’s interview with Larry Kaplan on the 2600 Connection website. Thanks also to Marty Goldberg for patiently corresponding with me and giving me Atari’s perspective, although I believe his conclusions about the Amiga/Atari negotiations and particularly his reading of the March 7 1984 agreement to be in error. And yeah, there’s my own book too…)