Sometimes great works go unappreciated during their time. Other times their time knows exactly what they’re on about. The latter was the good fortune of Elite, Ian Bell and David Braben’s epic game of space combat, trading, and exploration. Arriving at a confused and confusing time in the British games industry, Elite caused a rush of excitement the likes of which had never been seen before even in an industry that seemed to live and die on hype, becoming a bestseller several times over despite being initially released on a platform, the BBC Micro, that was not generally considered much of a gaming machine. Bell and Braben became recognizable stars, their names tripping off the tongues of a generation of British gamers the way that those of Lennon and McCartney had their parents’. It was about as close as the industry would ever get to Trip Hawkins’s dream of game designers as the rock stars of the 1980s. As for the game they created… well, that’s gone down into history as just possibly the most remembered and respected single computer game of the 1980s. But we’re beginning with the ending, which isn’t our usual way around here. Let’s go back to the beginning and see how it all began.

Bell and Braben first met one another during the autumn of 1982, when both arrived at Cambridge University as first-year undergraduates. Bell was to read math, Braben physics. More importantly, both were avid hackers. Bell brought a BBC Micro to university with him, Braben an example of that machine’s predecessor, the Atom, which he had expanded and soldered on and generally hacked at enough to make Dr. Frankenstein proud. Bell had real professional programming experience, at least of a sort: he’d gotten his version of Reversi published by a tiny company called Program Power, and would soon see an original action game, Freefall, published by Acornsoft, software arm of the company that made the computers on his and Braben’s desks. Braben had just passion and aptitude. The two bonded quickly.

Not that they became precisely bosom buddies. As their later story would demonstrate to anyone’s satisfaction, they were very different personalities. If I may strain an analogy just one more time, Bell was the John Lennon of the pair, pessimistic, introverted, and perhaps just a little bit tortured, while Braben was the Paul McCartney, an optimistic charmer with one eye on the market to go with one eye on his art. If not for their passion for Acorn computers, they would have likely had little to say to one another. Both, however, had programming talent to burn, along with a less obvious but at least as important instinct for visionary game design.

But then in the era of Elite even more so than today technological innovation and design innovation were often inextricably linked, with the latter most often flowing from the former. Thus the design that would become Elite stemmed directly from a routine Braben wrote in June of 1983 which could draw four different static 3D spaceships using wire-frame graphics. To understand what made those spaceships so different, and so fraught with potential, we should look to the state of game graphics in general circa 1983.

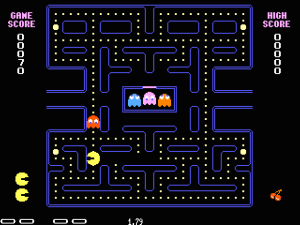

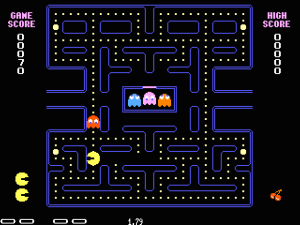

Almost all action games of 1983 or earlier show their world from either directly overhead or sideways (like Defender) or some odd hybrid of the two that doesn’t quite make sense in the real world (like Pac-Man). They employ a third-person perspective; you see and control an onscreen avatar from a distance, rather than viewing the world through his eyes. He, his enemies, and perhaps some other elements like laser fire move over a relatively static background image. This approach makes life much easier for programmers in at least a couple of ways. Updating big chunks of screen is very expensive in terms of the computing power available to early PCs and stand-up arcade games. Therefore many of them implemented hardware sprites, little movable chunks of graphics that exist separately from the rest of the screen inside the computer, to be overlaid onto it by the video hardware at no cost to the CPU only on the physical monitor screen. A game like Defender or Pac-Man is an ideal fit for such technology; I trust it won’t be difficult to figure out which parts of the screens above are implemented as sprites and which as background graphics. (In the early days all of the work could be left to sprites: a few early games, such as Boot Hill, consist of only sprites which are sometimes projected over a painted background image.)

There’s also another, more subtle advantage to the traditional arcade-game perspective. If you think about it for a moment, you’ll realize that the worlds shown on the screens above don’t correspond to any recognizable version of our reality even postulating that it could contain invading aliens or munching heads being pursued through a maze of food pellets by ghosts. These worlds are strictly 2D; they lack any notion of depth. Pac-Man and his friends are living in a computerized version of Edwin Abbott’s Flatland; if we were to see this world through his perspective, it would be a very strange one indeed. Similarly, your spaceship in Defender can go up and down and left and right, but not in and out. This is very convenient for the programmer because the computer screen also happens to be flat, possessed of an X- and a Y-dimension but no Z-dimension. Thus the coordinates of any object in this flat world being simulated correspond nicely to its coordinates on the physical screen.

But what if you aren’t satisfied with a Flatland-esque world shown from a locked vertical or horizontal perspective? What if you want to immerse your player in your world good and proper, and to make it one that corresponds to our own of three dimensions while you’re at it? Well, now your job just got a whole lot more difficult. As it happened, however, that was exactly what Bell and Braben were soon trying to do. The crux of the problem, the crux of a huge body of 3D graphics theory as well as lots and lots of specialized hardware that is probably a part of the computer you’re using to read this and for which if you’re a hardcore gamer you may have paid hundreds of dollars, is disarmingly simple: how to translate the X, Y, and Z of a world that lives inside the computer to the X and Y of the computer screen. The starting point must be the rules of visual perspective, well understood by artists since at least the Renaissance. But that well-trodden path opens into a thicket of complications when applied to the computer. Lacking as it does an artist’s intuitive understanding of the real world, a computer has to be laboriously instructed on how not to draw objects that are behind other objects on top of them, how to figure out which surfaces of an object are visible and which are not, etc. Just to make the challenges even greater, sprites aren’t of any real use for 3D graphics: the entire screen is necessarily changing all the time when moving a first-person perspective through a 3D world.

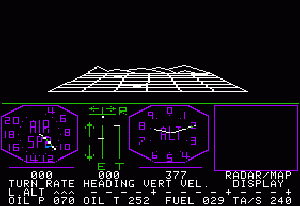

Bell and Braben were hardly the first to enter into this territory. Indeed, the field of 3D graphics isn’t all that much younger than the field of computer graphics itself. Academic researchers during the 1960s and especially the 1970s laid down much of the work that still grounds the field today. One minor contributor to this growing body of work was a graphics researcher and aviation enthusiast named Bruce Artwick, who finished a Master’s degree at the University of Illinois (home of PLATO) in 1976. For his thesis project, he combined his two interests. “A Versatile Computer-Generated Dynamic Flight Display” described a flight simulator featuring a first-person, out-the-cockpit view of a 3D world. In 1980, Artwick with his new company SubLogic brought to market the aptly titled Flight Simulator for the Apple II and TRS-80. Running in as little as 16 K of memory, it marked microcomputer gamers’ first encounter with the format that now dominates the industry: interactive, animated 3D graphics. The Flight Simulator line, whether sold under the imprint of SubLogic or Microsoft, went on to become a computing institution spanning some three decades.

Groundbreaking as they were, however, the early versions of Flight Simulator were also, as their name would imply, much more simulator than game. They provided no story, no goals, no sense of progression — just an empty world to fly through. Yes, they did include a mode called “British Ace 30 Aerial Battle,” which transformed your little Cessna into a World War I biplane and let you fly around trying to shoot other planes out of the sky, but, well, let’s just say that it was always clear when playing it that Artwick’s real priorities lay elsewhere. Mostly you were expected to make your own fun refining your piloting technique and, of course, marveling that this 3D world could exist at all on a 16 K 8-bit microcomputer.

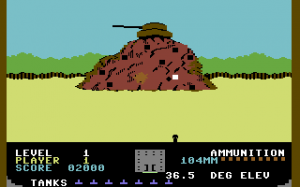

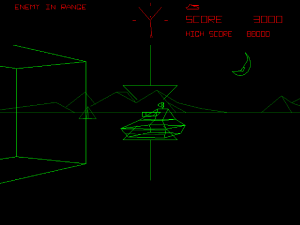

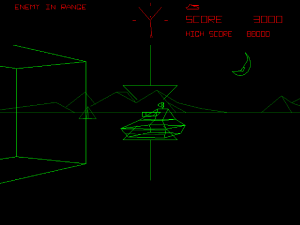

A more traditionally gamelike application of 3D came to arcades that same year in the form of Atari’s Battlezone. In it you control a tank in battle against other tanks. You view the action from a first-person perspective, through a screen made to resemble the periscope of a real tank. Battlezone eventually made it to home computers and consoles as well, albeit not until 1983. While their awareness of Flight Simulator is questionable (it was an American product made for American platforms in a very bifurcated computing world), Bell and Braben were aware of and had played Battlezone in the arcades. It was the impetus for Braben’s rotating 3D spaceships and for the combat game Bell and Braben would soon be designing around them.

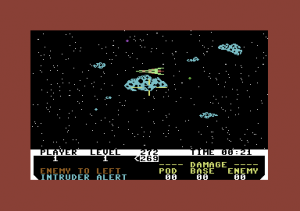

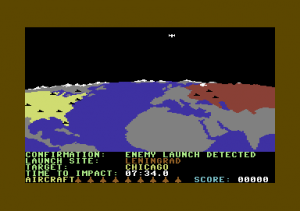

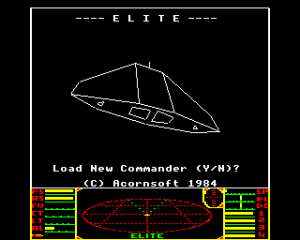

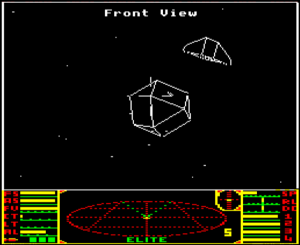

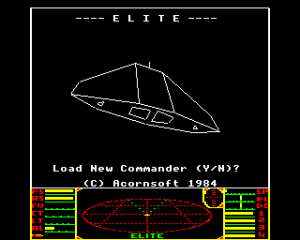

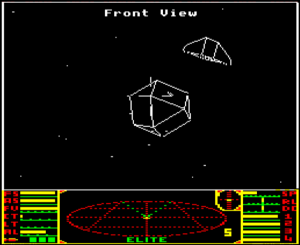

They were determined to bring 3D to a 2 MHz 8-bit computer with 32 K of memory, and to do it in the context of a real game with real things to do. At least they didn’t have to bemoan the uselessness of sprites to this new paradigm: having been created with educational and “practical” uses in mind rather than gaming, the BBC Micro didn’t have any anyway. Programming, like politics, being the art of the possible, compromises would be needed if they were to have a prayer. Braben had already made the wise choice to set his 3D demo in space. Space is full of, well, space. It’s almost entirely empty, thus dramatically reducing the amount of stuff their game would have to draw. One other obvious decision was to perform only the first part of the full two-part rendering process, drawing in the outlines of objects in their 3D world but not going back and filling in their surfaces, an even more complicated and expensive process. (As the screens above illustrate, Artwick and Atari had already made the same compromise in their own initial implementations of 3D.)

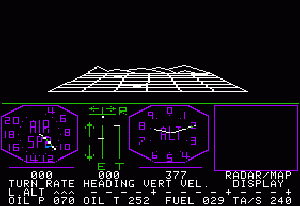

BBC Micro Elite. Note that the rendering is far from perfect, with lots of line breakage. Luckily, this isn’t so obvious when the ships are in motion.

Thus Braben made his first spaceships as simple as possible, with just enough lines and points to make of each a recognizable shape. This turned out to be wise for another reason: complex designs shown in wireframe tend to turn into a confusing mishmash of lines. To simplify rendering, all objects were also made convex, meaning that any given line will only pass in and out of the object once; as Braben himself put it in a talk at a recent Game Designers Conference, a block of cheddar cheese is convex but a block of Swiss is not. Later in the game’s development, when Bell and Braben had managed to considerably accelerate the original rendering code, more complex ships, like Bell’s Transporter, were added.

Another area of concern must be your control of your own spaceship, the one through whose cockpit you would be viewing this 3D universe. A spaceship, like an airplane, can change its orientation in six ways, being able to yaw, pitch, or roll in either direction. Yet a joystick can be moved in only four cardinal directions — perfect for a 2D world but problematic for their 3D world. Bell and Braben soon realized, however, that being in space saved them. With no ground, and thus no real notion of up and down with which to contend, turns could be accomplished by simply rolling to the desired orientation and pitching up or down; no need for a yaw control at all. While they took full advantage of the good parts of being in space, they also wisely decided not to try to make the game a remotely realistic simulation of spaceflight. Like Star Wars, their game would be one of dogfights in space, with ships inexplicably subject to a law of inertia that should have been left planetside. Anything else would just feel too disorienting, they judged. Most people would prefer to be Luke Skywalker rather than David Bowman anyway.

So, yes, this would be a game of space combat. That was always a given. But what should it be beyond that? How should that combat be structured, framed? With a workable 3D engine running at last after some months of concerted effort, it was time to ask these questions seriously. One alternative would be to make a traditional arcade-style game, complete with three lives, a score, and ever-escalating waves of enemy ships to gun down. To make, in other words, Battlezone with spaceships. Certainly what they already had was more than impressive enough to sell lots of copies.

Instead, Bell and Braben made their next visionary decision, to make their game something much more than just an arcade-style shooter. They would embed the shooting within a long-form experience that would give it a context, a purpose beyond high-score bragging rights. This was not, as effervescent popular histories of Elite‘s birth have often implied, completely unprecedented. Long-form experiences were not hard to find in computer games years before Bell and Braben — in adventures, in CRPGs, in strategy and war games. It was, however, rather more unusual to see this approach combined with action elements. Taken on their own, the action elements of Bell and Braben’s game were groundbreaking enough to go down as an important moment in gaming history. By refusing to stop there, they would ensure that their game would break ground in multiple directions, and go down as not just important but one of the most important ever.

The inspiration came from tabletop RPGs, a pastime both Bell and Braben indulged in from time to time, although, perhaps tellingly, usually not together. They liked the way an RPG campaign could span many, many sessions, could turn into an ongoing long-form narrative. And they liked the process of building up a character from a low-level nothing to a veritable god over weeks, months, or years. Of course, your “character” in their game was really your spaceship. Fair enough; your goal would be to upgrade that with ever better weapons and defenses that not coincidentally bore a strong resemblance to those in Bell’s favorite RPG: Traveller, the first popular tabletop RPG to replace swords and sorcery with rockets and rayguns. From here the rest of the design seemed to unspool almost of its own accord.

They needed a mechanism for upgrading the ship, something more interesting than just adding the next piece to the ship automatically every time a certain score threshold was reached. The natural choice was money; every option would have a cost, letting players prioritize and truly make their spaceships their own.

Okay, but how to earn money? Drawing again from Traveller (a game whose imprint would be all over the finished Elite not just in mechanics but in its overall feel), you could be a trader plying the spaceways, buying low in one system in the hopes of selling high in another — a whole new strategic dimension.

But then how would that involve combat? Well, the ships attacking you could be pirates. This would also go a long way to explain why they were so chaotic and kind of random in their behavior, an inevitable result of limited memory and horsepower to devote to their artificial intelligence. Pirates, after all, were chaotic and kind of random by their very nature.

But actually landing on all those trading planets obviously wasn’t going to be workable; avoiding those complications was the reason for setting the game in space in the first place. No problem; you could just dock at space stations in orbit around them. Bell and Braben came up with a new challenge to make this more interesting: in a bit inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey, you would have to carefully guide your spaceship into the rotating station’s docking bay at the end of every voyage. Of course, over time this could get tedious as well as frustrating (a botched approach generally means instant death). No problem; for a mere 1000 credits, you could buy a docking computer to do it for you. Other non-combat-oriented ship upgrades were also added to the catalog, like a fuel scoop to gather fuel by skimming the surface of a sun instead of buying it at a station.

If those spaceships attacking you really were pirates, thought Bell and Braben, the authorities would probably be quite pleased with you for shooting them down. Why not put bounties on them, so you could make your living as a bounty hunter if you got bored with trading? Now the possibilities really started rolling. If you could shoot pirates for money, you could also attack peaceful traders — become a pirate yourself, in other words, if you felt you could outduel the police Vipers that would attack you from time to time once your reputation became known. They came up with an alternative use for the fuel scoop: use it to scoop up the cargo of ships you’d destroyed to sell on the stations. The fuel scoop also became key to yet another way of making money: buy a special mining laser, break up asteroids with it, and scoop up the alloys they contained to sell stationside. If only they’d had more than 32 K of memory, they could have gone on like this forever.

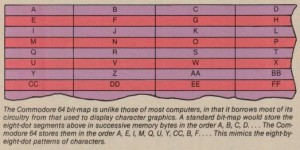

But 32 K was all they had, and that was a constant challenge to their growing ambitions. For this grand game of trading to work, there had to be a big, varied galaxy to explore. There should be planets with a variety of economies and governments, from safe, established democracies for the conservative, peaceful trader to visit to anarchies home to hordes of pirates for the brave or foolhardy looking to make a big score. They came up with a scheme to let them pack all of the vital information about a star system with a single inhabited planet — its location, its economy, its type of government, its technology level, its population, its dominant species, its GDP, its size, even its name and a bit of flavor text — into just six bytes. Even so, a modest galaxy of 100 star systems would still require 600 bytes that they just couldn’t seem to find. Now came their most storied stroke of inspiration.

In 1202 an Italian mathematician named Fibonacci described a simple construct that became known as the Fibonacci sequence. In its classic form, you begin with two numbers, either 1 and 1 or 0 and 1. To get the third number in the sequence, you add the first two together. You then add the second and third number together to get the fourth. Etc., etc. A common and very useful variation is to drop all but the least significant digit of each number that is generated. It’s also common to begin the sequence not with 1 and 1 or 0 and 1 but some other, arbitrary pair. So, a sequence that begins with 2 and 7 would look like this:

2 7 9 6 5 1 6 7 3 0 3 3 6 9 5 4 9 3 …

The sequence appears random, but is actually entirely predictable for any given starting pair. This variation, however, is only a starting point. You can apply any rules you care to specify to a sequence of numbers with entirely predictable results, as long as you are consistent about it. Bell and Braben realized that they could seed their galaxy with any sequence they wished of six hexadecimal numbers to represent the starting system. Then they could manipulate those numbers in a predetermined way to generate the next; manipulate those to generate the next; etc. They decided that 256 systems was a good size for their galaxy. They needed just those initial six bytes to “store” all 256 planets. In addition to the memory savings, this method of generating their galaxy also saved Bell and Braben many hours spent designing it from scratch. Indeed, growing new galaxies from different starting seeds soon became a game of its own for them. They went through many iterations before finding the one that made it into the final game. Some they had to throw out right away for obvious reasons, such as the one with a system called “Arse” and the ones that had unreachable systems, outside of the player’s ship’s seven-light-year range from any other stars. Others just didn’t feel right.

After a few months of steady work, the basics of what would become Elite were all in place in their heads if not entirely in their code. They decided it was time to see if anyone would be interested in publishing it. Braben believed they should try to find the biggest publisher possible, one with the reach to properly support and promote this game like no other. He accordingly secured them an appointment at the London offices of Thorn EMI, the recently instantiated software division of one of the largest media conglomerates in the world. Very much a sign of this heady period in British computing, Thorn EMI had been founded in the expectation that computer games were destined to be the next big thing in media. Like their colleagues over in EMI’s music division looking for the next big hit single, they weren’t looking for deathless art or niche audiences; they were looking for big, mainstream hits. They had developed a checklist of sorts, a list of what they thought would appeal to the general public that wasn’t all that far removed from Trip Hawkins’s guidelines for American “consumer software.” Their games should be simple, intuitive, colorful, and not too demanding. Bell and Braben’s complicated game — while it was a technical wonder; anyone could see that — was none of these things. They said it was nothing for them, although Bell and Braben were welcome to come back any time to show a reworked — i.e., simplified — version. (In the end, Thorn EMI would find that technology wasn’t ready for casual consumer software, and wouldn’t be for years. The hardcore was all they had to sell to. Unwilling or unable to adapt to this reality as Hawkins’s Electronic Arts eventually did, they faded away quietly without ever managing to find the breakout mainstream hit they sought.)

Bell suggested they try Acornsoft, who had already published his game Freefall. In many ways Acornsoft should have been the logical choice from the start. Bell already had connections there, they knew the BBC Micro better than anyone, and they were located right there in Cambridge practically next door to the university proper, an institution with which they had deep and abiding links. (Regular readers will remember that it was Acornsoft and Cambridge oceanography professor Peter Killworth who provided a commercial outlet for the adventure games created on Cambridge’s Phoenix mainframe.) Yet Braben was reluctant. Always the more commercially minded of the pair, he knew that Acornsoft was hardly at the forefront of the British games industry. Their modest lineup of adventure games, educational software, and utilities had some very worthy members, yet the operation as a whole, like most software adjuncts to hardware companies, always felt like a bit of an afterthought. With their limited advertising and doughtily minimalist packaging, no Acornsoft title had ever sold more than a few tens of thousands of copies, and most never cracked 5000 — a far cry from the numbers Braben fondly imagined for their game. Acornsoft’s association with Acorn also concerned him in that it would necessarily limit the game to only Acorn computers. He and Bell weren’t hugely fond of the Commodore 64 or especially the Sinclair Spectrum, but he knew that their game would have to be ported to those more prominent gaming platforms at some point if it was to realize its commercial potential. In short, Acornsoft was… provincial.

Still, he agreed to accompany Bell to Acornsoft’s offices. It was, to say the least, a place very different from Thorn EMI’s posh digs in central London. From Francis Spufford’s Backroom Boys:

[Acornsoft] operated from one room of a warren of offices above the marketplace. You got there by sidling around the dustbins next to the Eastern Electricity showroom. Past the window display of cookers and fridge-freezers, up a steep little staircase, and into a cramped maze that would remind one employee, looking back, of a level from Doom. “Very back bedroom,” remembered David Braben, approvingly. In Acornsoft’s office they found a rat’s nest of desks and cables, and four people not much older than themselves.

Two of those four people, managing director David Johnson-Davies and chief editor Chris Jordan, would become the unsung heroes of Elite. Both got the game immediately, grasping not just its technical wizardry but also Bell and Braben’s larger vision for the whole experience. They both realized that this thing had the potential to be huge, bigger by an order of magnitude than anything Acornsoft had done before. Of course, it also represented a risk. Bell and Braben looked and acted like the couple of headstrong kids they still were. What if they flaked out? Nor was Acornsoft accustomed to issuing contracts and advances on unfinished software. Acornsoft had been conceived as an outlet for moonlighters and hobbyists, who sold them their homegrown software only once it was finished. Their normal policy was to not even look at programs that weren’t done; Bell and Braben were there at all only as a favor to Bell, a fellow with whom Acornsoft had a history and whom they liked personally. Still, Acorn as a whole was doing well; there was enough money to try something new, and this was too big a chance to pass up. They offered Bell and Braben a contract and an advance.

Now Braben made a move that would be as critical to Elite‘s success as anything in the game itself. Still concerned about Acornsoft’s provinciality, he negotiated a non-exclusive license which would allow them to develop and market versions for other machines after the versions for the Acorn machines were finished. Not quite sure what he was on about, Johnson-Davies agreed. With his share of the advance, Braben bought his own BBC Micro, retiring his hacked and abused old Atom at last.

As Bell and Braben worked to finish their game, Acornsoft provided essential playtesting while Johnson-Davies and Jordan served as an invaluable source of guidance and a certain adult wisdom. Sometimes the latter was needed to keep their ambitions in check, as when Bell and Braben burst into the Acornsoft office one day having had an epiphany. They had realized that, if all they needed to grow a galaxy was a starting seed of six numbers, they could have an infinite number of them — well, okay, about 282 trillion of them — in the game. They could let the player buy a “galactic hyperdrive” to jump between them, whereupon they would just generate a new random seed and let it rip. Johnson-Davis now showed a sharp design instinct of his own in walking them back a bit. Having more galaxies sounds like a great idea, he said, but having so many will actually spoil the illusion of a real persistent universe you’ve worked so hard to create. It will all just start to feel like what it really is: random. Nor will many of these new galaxies be pleasing places to explore, since you won’t be able to look at them and reject the ones with unreachable systems and the like. Bell and Braben agreed to settle for just eight galaxies, with a total of 2048 star systems to visit. That should be more than enough for anyone. Perhaps too many for Bell and Braben and Acornsoft’s testers: a planet Arse sneaked into one of these later galaxies and made it into the released version of the game.

Even as they gently squashed some of Bell and Braben’s more outlandish ideas, Johnson-Davies and Jordan still felt like something was missing. For all its technical and formal innovations, for all its scope of possibility, the game lacked any sort of real goal. Now, to some extent that was just the nature of the beast Bell and Braben had created. They would have dearly loved to have a real story to give context, had even planned on it at some stage (Braben says that “trading was originally going to be a very minor aspect”), but they now had to accept the fact that they weren’t going to be able to wedge some elaborate plot along with everything else into 32 K. Still, suggested Johnson-Davies and Jordan, maybe they could add something simple, something to mark progress and give bragging rights. Thus was born the system of ranks, based on the number of kills you’ve achieved. You start Harmless. After notching eight kills you become Mostly Harmless (a nod to The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy). Each rank thereafter is exponentially more difficult to achieve, until, after some 6400 kills, you become Elite. There was the goal, one that should keep players playing a good long time.

It was also in a backhanded sort of way a political statement. Cambridge University was awash with indignation over the policies of Margaret Thatcher; a major coal-miner’s strike which would become the battlefield for Thatcher’s final vanquishing of organized labor had the university’s liberal-arts wings all in a tumult from March of 1984. Bell and Braben bucked the university conventional wisdom to side with Thatcher. The player’s goal of becoming Elite was meant as a subtle nod toward the libertarian ideal of the self-made man, and a little poke in the eye of their leftist acquaintances. It also emphasized their view of their game as fundamentally about space combat, not trading. It gave players a compelling motivation to engage with what Bell and Braben still regarded as the most compelling part of the experience. You can make a lot of money as a peaceful, law-abiding trader who prudently runs from pirates when they show up, but you’ll never make Elite that way.

In finding an overarching goal they also found the title they’d been searching for for some time. They first planned to call the game The Elite, a name to celebrate the group that much of Cambridge was railing against. But the filenames used for the game just said “Elite.” In time, they dropped the article from the official title as well. Elite it became — shorter, punchier, and with fewer political ramifications for Acornsoft to deal with.

Similarly subtle swipes at Cambridge’s liberal-arts students, whom in the long tradition of hard-science students Bell and Braben regarded as mushy-minded prima donnas, made it into the text tables that Bell developed to describe the planets in the game. After the Fibonacci sequence had done its work, some were populated by “edible poets”; others by “carnivorous arts graduates.” Ah, youth.

Bell and Braben had disk drives on their BBC Micros. After compressing their code as much as they possibly could, they finally began to make use of their capabilities within the game. They split the game into two parts: the trading program, loaded in when you docked at a station, and the program handling travel and combat, loaded as soon as you left one. This concerned Acornsoft greatly because most BBC Micro owners still had only cassette drives, which didn’t allow such loading on the fly. What good was the game of the decade if most people couldn’t play it? So they convinced the two to fork the game three ways. One version, the definitive one with all the goodies, would indeed require a BBC Micro with a disk drive. Another, for a tape-equipped BBC Micro, would be similar but would offer a smaller variety of ships to encounter along with simplified trading and a bit less detail to planets you visited and to the overall experience. Finally, Acorn convinced them to create a third version, stripped down even more, for the BBC Micro’s little brother, the Acorn Electron, an attempt to compete with the cheap Sinclair Spectrum that Acorn had introduced the previous year.

Bell and Braben were naturally most excited about the disk-based version, particularly when they realized they had enough space still to add a little something extra. They made a couple of hand-crafted “missions” that pop up when you’ve been playing for a while: one to hunt down and destroy a stolen prototype of a new warship, another to courier some secret documents from one end of the galaxy to the other. These gave at least a taste of the more prominent story elements they wished they had space for.

While Bell and Braben finished up the coding, Johnson-Davies and Jordan worked to give the game the packaging and the launch it deserved. Acornsoft figured they needed to do all they could to justify the price they’d chosen to charge for the thing: from £12.95 to £17.65 depending on version, well over twice the typical going rate for a hot new game. They prepared a box of goodies the likes of which had never been seen before, not just from bland little Acornsoft but from anyone in the British games industry. Only some of the more lavish American packages, like those for the Ultimas and various Infocom games, could even begin to compare, and even by their standards Elite was grandiose. To a 63-page instruction manual Johnson-Davies and Jordan added The Dark Wheel, a separate scene-setting novella they commissioned from Robert Holdstock, an author just about to come into his own with the publication of his novel Mythago Wood. And they still weren’t done. They also added a ship-identification poster, a quick-reference guide, a keyboard overlay, some stickers, and a postcard to send to Acornsoft to tell them about it and get your certificate of achievement when you achieved the rank of Competent (an onscreen code revealed at that point would serve as proof).

Acornsoft stepped in and froze further development during the summer of 1984. The packaging was just about ready, and work on the game, while it would never be truly finished in the eyes of Bell and Braben, struck Acornsoft as about to reach a point of diminishing returns. And everyone was a little bit paranoid that something similar to Elite, even if it was nowhere near as good, might come out and steal their thunder. Bell and Braben grudgingly agreed that the time for release had come. But then, just as Acornsoft was about to send the master disk for duplication, Braben called Chris Jordan in a frenzy. They’d solved a niggling problem that had been bothering everyone for months, that of a “radar” scope to show where enemy ships are in relation to your own. The problem was, again, that of trying to map three dimensions onto two. Bell and Braben had done the best they could by providing two complementary scanners that had to be read in conjunction to get the full picture, but it always felt, in contrast to just about everything else about the game, kind of clunky and un-ideal. Now they had come up with a way to pack everything onto a single screen. It was beautiful. Showing a commitment few publishers then or now could match, Acornsoft agreed to take the new version of the game, which brought with it the painful task of having the manual edited and re-typeset to describe the new radar scope. Now, two years after Braben had first started playing with 3D spaceship models, they were done.

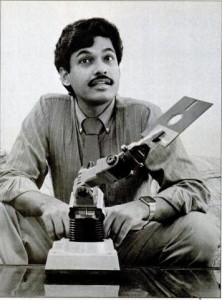

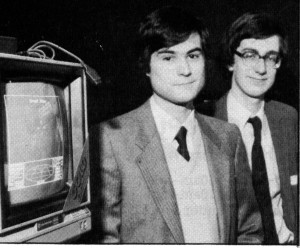

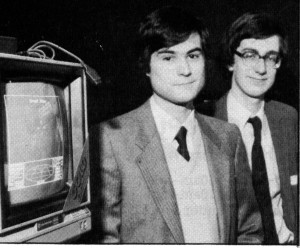

Buzz about Acornsoft’s secret “Project Bell” had been high for months. Acornsoft rented for launch day Thorpe Park, a small amusement park (nowadays a much bigger one) near London. In a darkened room, with suitably portentous music playing, the world got its first glimpse of Elite — and of its two creators, who for the next few years would be the face of the young British games industry. In their picture from the launch party they look much as the British public would come to know them: Braben in the foreground, glib and personable; Bell a bit more uncertain and stereotypically nerdy and, much to Acornsoft’s occasional chagrin, more liable to go off-script.

Elite itself, needless to say, became a hit. Acorn and Acornsoft were making a big play for the home-computer market that Christmas, trying to challenge Sinclair and Commodore on their own turf, and Elite became a big part of that push. Advertising was shockingly frequent and grandiose for anyone who remembered the Acornsoft of old. The £50,000 campaign even included some television spots. Acornsoft Elite eventually sold almost 150,000 units between the BBC Micro and the Electron, a huge number for an absurdly expensive game on platforms not particularly popular with gamers. And most of those customers seemed to play Elite with an enthusiasm bordering on the obsessive. The first person known to become Elite was one Hal Bertram, on November 3, 1984, about five weeks after the game’s release. By the end of the year he had many companions in glory, while Acornsoft was positively flooded with postcards sent in by those attaining at least Competent status; they could barely make the badges they sent back to these folks fast enough. Many were doubtless aided by a bug in the ship-equipping code that had slipped through testing and was soon making the rounds amongst players: you could make infinite cash by trying to buy a laser you already had, whereupon the game would reward you with a generous cash credit in addition to the expected refusal. Undeterred, Acornsoft fixed the bug and sponsored a series of live monthly contests culminating in a grand showdown at the Acorn Users Show.

Still, it was clear to Braben that the really big numbers would come only when Elite came to the Speccy and the Commodore 64. The game was the talk of the industry, with owners of those more popular platforms, who had not even been aware of Acornsoft’s existence a few months ago, clamoring to play it after it — along with its creators — began appearing in places like Channel 4 News.

And now we see the significance of that non-exclusive license Braben had negotiated. He heard through the grapevine about a former literary agent named Jacqui Lyons, who had recently become the first agent representing game developers in Britain. Lyons:

A friend rang up and told me about Ian Bell and David Braben. Elite had just happened and Ian and David had retained all rights other than for the BBC, which was extremely bright of them. They wanted me to represent the rest of those rights.

With virtually every publisher in Britain dying to publish Elite for the other, more popular gaming platforms, Lyons decided that there was one foolproof way to find out who really wanted it, and to make sure her new clients got served as well as possible in the process — i.e., paid as well as possible. At the beginning of December she held an auction, which, in her own words, “caused a lot of trouble in the industry — I was told this was an appalling way to go about it.” Lyons responded that such an approach was common in the publishing world from which she hailed. And what better way to ensure that your publisher would put everything they had into a game than to make them pay as dearly as possible for it? The deep pockets of British Telecom won the day amidst a flurry of media interest. Having just entered the software market with a new imprint called Firebird and eager to make a big splash with the highest-profile game in the industry, BT paid an undisclosed but “substantial” sum — Bell and Braben each got six figures up-front — for publishing rights to Elite on all platforms other than the Acorn machines. Suddenly Bell and Braben, who had yet to receive their first royalty checks from Acornsoft, were very wealthy young men.

For their part, Acornsoft allowed Bell and Braben to move on without fighting at all to retain Elite as a desperately needed platform exclusive. Indeed, they handled Bell and Braben’s departure with almost incomprehensibly good grace, even working out agreements to allow Firebird to reuse most of the wonderful supplemental materials they had stuffed into that bursting box. Perhaps they just had bigger fish to fry. Elite, you see, was the sole bright spot in a disastrous Christmas for Acorn as a whole, one rife with miscalculations which effectively wrecked the company. A desperate Acorn was purchased by the Italian firm Olivetti in 1985, and became thereafter a very different sort of place. The Acornsoft label was retired barely a year after the Elite launch, with Johnson-Davies and Jordan and all of their colleagues going on to other things.

But the game they had introduced to the world was just getting started. Bell and Braben themselves ported it to the Commodore 64. That version is not quite as fast and smooth as the BBC version — the 64’s 6502 is clocked at just 1 MHz instead of the BBC’s 2 MHz — but took advantage of the 64’s better graphics and its positively cavernous 64 K of memory to add in compensation more color and a welcome touch of whimsy to undercut its otherwise uncompromisingly dog-eat-dog world. There’s a third special mission, this one a bit of silliness drawn from the beloved Star Trek episode “The Trouble with Tribbles.” When the tribble — excuse me, “trumble” — population aboard your ship has mushroomed to the point that the little buggers start crawling around the screen in front of you, it’s laugh-out-loud funny, even if it is just about impossible to figure out how to get rid of them absent spoilers. But best of all is the new music which plays during the automated docking sequence: Johann Strauss’s “The Blue Danube,” a tribute to everyone’s favorite part of 2001: A Space Odyssey. It comes as a complete surprise (if you haven’t read an article like this, that is…) when you first flip the switch to try out your hard-won docking computer and are greeted with this unexpected note of easy beauty. Soon your travels assume an addictive rhythm: the calculus of buying and selling, followed by the tension and occasional excitement of the voyage itself, followed by the grace notes of “The Blue Danube,” when you know you’ve survived another voyage and can sit back and enjoy a few minutes of peace before starting the process over again. Life in a microcosm?

The Commodore 64 Elite established a tradition of each port being largely hand-coded all over again; this gives each its own feel. Scottish developers Torus took on the challenging task of converting Elite to the Spectrum, which is built around a Z80 rather than the 6502 microprocessor at the heart of the BBC Micro and Commodore 64. Speccy Elite arrived several months after the Commodore 64 version and about a year after the original, touching off another huge wave of sales. Amidst the usual slate of added and lost features, it added yet more special missions, for a total of five. Missions became the most obvious way for the many individual developers who worked on Elite over the years to put their own creative stamp on the game, a trend actively encouraged by Bell and Braben; “just have your own fun” with the missions was always their response to requested advice. About the same time as the Spectrum Elite arrived in Britain, Firebird brought the Commodore 64 Elite to the United States, where it — stop me if you’ve heard this before — became a huge hit, one of relatively few games of the 1980s to make a major impact in both the European and North American markets. It served to establish Firebird as an important publisher in the U.S., the first such to be based in Britain and one which would give many other British games deserved exposure in that bigger market.

The ball was now well and truly rolling. For almost a decade the existing versions just kept on selling and the ports just kept on coming: to big players of the era like the IBM PC, the Apple II, the Atari ST, the Commodore Amiga, and the Amstrad CPC as well as occasional also-rans like the Tatung Einstein. Even the Nintendo Entertainment System got a surprisingly faithful and enjoyable version in 1991. In the end Elite made it to 17 separate platforms. Ian Bell has guessed in one place that it sold about 600,000 copies. David Braben claims that Elite surpassed 1 million copies worldwide, but this claim is much more dubious. Regardless of the final tally, Elite was certainly amongst the most commercially successful born-on-a-PC games of the 1980s.

Bell and Braben’s mainstream fame proved to be almost as enduring — in September of 1991 The One magazine could still write about the latter as “the most famous developer in Britain” — but their partnership less so. The two tried for some time to make Elite II for the BBC Micro and the Commodore 64, but never got close to completing it for reasons which vary with the teller. In Bell’s version, the game was just too ambitious for the hardware; in Braben’s, Bell was more interested in enjoying his new wealth and practicing his new hobby of martial arts than buckling down to work. Braben alone finally made and released Frontier: Elite II, a hugely polarizing sequel, in 1993. The erstwhile partners then spent the rest of the decade in ugly squabbles and petty lawsuits. To the best of my knowledge, the two still refuse to speak to one another. While both agreed to give talks upon the game’s 25th anniversary at the GameCity Festival in Nottingham in 2009, they agreed to do so only if they didn’t have to share a stage together. Like most people who have studied their history, I have my opinions about who is the more difficult partner and who is more at fault. In truth, though, neither one comes out looking very good.

Bell retired quietly to the country many years ago to tinker with mathematics, martial arts, and mysticism. He hasn’t released a game since the original Elite. Braben, in contrast, has built himself a prominent career as a designer and executive in the modern games industry. If he’s no longer quite the most famous developer in Britain, he’s certainly not all that far out of the running. He recently Kickstarted a new iteration of the Elite concept called Elite: Dangerous to the tune of more than £1.5 million, proof of the game’s enduring place in even the contemporary gaming zeitgeist and its enduring appeal as well as the cachet Braben’s name still carries.

And what is the source of that appeal? As with any great game for which it all just seemed to come together somehow, that can be a difficult question to fully answer. I could talk about how it was one of the first games to show the immersive potential of even the most primitive of 3D graphics, prefiguring the direction the entire industry would go a decade later. I could talk about how it was one of the first to graft a larger context to its core action-based gameplay, giving players a reason to care beyond wanting to run up a high score. I could talk about how perfectly realized its universe is, how it absolutely nails atmosphere; its cold beauty is just that, beautiful. Those minimalist wireframe spaceships are key here. I never quite felt that later iterations for more advanced platforms, which fill in the spaceships with color, felt quite like Elite. But then I suspect that for most folks the definitive version of Elite is the one they played first…

Maybe the most impressive thing that Elite evokes is a sense of possibility. You really do feel when you start playing, even today, even when you’ve read articles like this one and know most of its tricks, that you can go anywhere (as, given time and patience, you can), and that anything might happen there (okay, not so much). Yes, over time, especially over these jaded times, that sense fades, this Fibonacci universe starts to lose some of its verisimilitude, and it all starts to feel kind of samey. I must confess that when I played again recently for this article that point came for me long before I got anywhere close to becoming Elite. I think for the game to last longer for me I’d need some more of those story elements Bell and Braben originally hoped to include. But just the fact that that feeling is there, even for a little while, is amazing, the sort of amazing that makes Elite one of the most important computer games ever released. In addition to being a great play in its own right, it represents a fundamental building block of the virtual worlds of today and those still to come.

(In addition to being such a huge hit and such a seminal game historically, Elite comes equipped with a very compelling origin story. Together these factors have caused it to be written and talked about to a degree to which almost no other game of its era compares. Thus my challenge with this article was not so much finding information as sorting through it all and trying to decide which of various versions of events were most likely to be correct.

The lengthiest and most detailed print chronicle of all is that in the book Backroom Boys by Francis Spufford. More cursory histories have been published by Edge Online and IGN. Vintage sources used for this article include: Your Computer of December 1984; The One of January 1991 and September 1991; Micro Adventurer of January 1985; Home Computing Weekly of December 11, 1984; Personal Computing Weekly of August 23, 1984. David Braben’s talk at the 2011 Game Developers Conference was a goldmine, while Ian Bell’s home page has a lot of information in its archives. Other useful fan pages included FrontierAstro and The Acorn Elite Pages. And when you get bored with serious research, check out the Elite episode of Brits Who Made the Modern World, which in its first ten seconds credits the game with starting the British games industry and goes on to indulge in several other howlers before it’s a minute old. It makes a great example of the hilariously hyperbolic press coverage that always clings to Elite.

Finally, rather than provide a playable version of Elite here I’ll just point you once again to Ian Bell’s pages, where you’ll find versions for many, many platforms.

Updated June 14, 2014 and July 14, 2014: I heard from Chris Jordan, who set me straight on more than a few facts and figures found in the original version of this article. Edits made.)