I would rather see a personal vision onscreen than filmed live-action. I have an idea that with CD technology there are going to be a lot of little-known actors photographed and appearing on our screens. I think if you have a graphic artist involved, you get something even better than reality.

— Dave Gibbons

There’s no reason why hundreds of people in California should know the future any better than ten people based in Yorkshire.

— Charles Cecil

Charles Cecil was a part of the British adventure-games scene from the beginning. Born in 1962, he began studying engineering at Manchester University in 1980. There he became friends with a fellow student named Richard Turner, who had just co-founded Artic Computing, one of the very first suppliers of software for the Sinclair ZX80, Britain’s very first mass-market personal computer. Although he was not and never would become a programmer, Cecil got pulled into other aspects of the venture, such as drawing what he describes today as “the shittiest logo.”

Chris Thornton, Richard Turner’s partner in Artic, owned an imported Radio Shack TRS-80; this allowed the group of friends to keep tabs on the American microcomputing scene, which had a few years’ head start on the British. Taking note of the success that Scott Adams was having with his text adventures in the United States, Artic developed an engine for similar games on Sinclair machines. In June of 1981, Turner and Thornton’s Adventure A: Planet of Death became the first home-grown adventure game ever to be sold in Britain.

As the name of that first game would imply, Artic intended from the beginning to make a whole line of text adventures, just as Scott Adams had done. “You like telling stories,” Turner said to Cecil. “Why don’t you write one?” Thus Cecil designed Adventure B: Inca Curse, followed by several more text adventures, all primitive enough — or, if you like, minimalist enough — to fit into a computer with just 16 K of memory. A game designer had been born, alongside a cottage industry of similarly ramshackle semi-professional text adventures that would persist for the better part of two decades. (Artic’s games were particularly noted for their atrocious spelling…)

Cecil continued to design games and do various other odd jobs for Artic for several years, but by the middle of the decade the company’s homespun products were finding the going tough in what had now become a crowded and hyper-competitive British software market. In 1985, Cecil jumped from the sinking ship to found his own Paragon Programming, which specialized in porting American games to European platforms. Two years later, he parlayed that into a short-lived gig as development manager for US Gold, then a longer-lived one in the same role for Activision’s European subsidiary.

But a series of unfortunate events and poor management decisions at the American parent company — a trend which began about the time of Cecil’s arrival, with management’s decision to change the company’s name to the hopeless corporatese “Mediagenic” — ultimately spelled disaster for that international software empire. In 1990, the 27-year-old Charles Cecil, who had recently been enjoying such luxuries as a posh company car and a mobile phone, was left high and dry by Mediagenic’s collapse. What to do now?

All his time spent porting and selling American games had given him a familiarity with goings-on across the Atlantic that was unusual among his countrymen. The one area of gaming where the Americans most obviously outdid the Brits, he realized, was the genre he still loved best: the adventure game. British and, indeed, most European developers had little that could compete with the latest graphic adventures from American publishers like Sierra and Lucasfilm Games. There was a reason for this: thanks to their need for large amounts of single-use visual and audio assets, those games were among the most expensive of all to produce; European studios for the most part simply lacked the resources to make them. The one partial exception to this rule came in the form of a few French studios like Delphine, who made games that were beautiful to look at if often atrociously designed. But Britain had absolutely nothing on offer.

So, Cecil decided for the second time in his young life to found his own company, with the intention of changing that — this despite the fact that he had very little money at all to work with even by the modest standards of British game development. He started Revolution Software in March of 1990 on the back of a £10,000 loan from his mother, and took up residence in an unheated cubbyhole above a fruit market in the struggling city of Hull — “We chose Hull because it was cheap,” admits Cecil — with a few of the folks he’d met during his previous travels through the British games industry. The setting verged on the Dickensian; during the winter months, they would huddle against their computers to try to stay warm.

Still, Cecil did soon convince the British publisher Mirrorsoft to provide some minimal funding for Revolution’s first game in return for the publication rights to the eventual finished product. When Mirrorsoft collapsed in the wake of the suspicious death of its kingpin Robert Maxwell and the postmortem revelation of financial improprieties throughout his organizations, they moved on in fairly short order to Virgin Games — a better partner on the whole, as Virgin came complete with a North American branch.

The core team at Revolution in the early days: Tony Warriner, Adam Tween, David Sykes, Stephen Oades, Dave Cummins, and Charles Cecil.

Tacitly admitting that it would be difficult indeed for a shoestring operation like theirs to compete with a company like Sierra in terms of production values, Revolution settled on a concept and engine to power it which they called “Virtual Theatre.” They envisioned it as nothing less than the next great leap in adventure design. Cecil described it thusly at the time:

Within each game, time advances and people walk around with their own routes: the blacksmith will go into his forge and hammer away, then he’ll go into the pub to have a drink and he’ll talk to other people around the village. You could have fifteen people all walking around, all interacting with each other. So instead of being a game where you’re the key and everything reacts to you, we have a game where you’re just another person.

It was a noble vision in its way, one which aimed to push the frontiers of an oft-hidebound genre. And yet, for all that it reads well on paper, it would prove more than problematic in practice. The disadvantage of making a world which runs along of its own accord is that it can run merrily away without the player, leaving her stranded in some plotting cul de sac. And then, far from being a drawback, most players enjoy adventure games precisely because they let them be the star of the show. After all, If one wants a world where one is “just another person,” one generally need only look up from the computer.

When Cecil expanded yet further on his vision, he wound up in a place to which many designers have dreamed of venturing since the heyday of commercial text adventures, but which has yet to yield a single comprehensively satisfying game: “What we’re planning to do in the future is put in artificial intelligence whereby we set the basic parameters and then we let the characters decide what they’re going to do themselves. Fundamentally, anything could happen.”

Unsurprisingly, then, the first Revolution game — the one which most wholeheartedly embraced the Virtual Theatre concept — also proved to be the worst one they would ever make. Lure of the Temptress combined a clichéd fairy-tale setting with an awkward interface, sub-Sierra graphics, and well-nigh infuriating gameplay, which mostly entailed chasing all of those vaunted self-directed characters hither and yon through a plot line littered with potential dead ends. Published internationally by Virgin Games for the Commodore Amiga, Atari ST, and MS-DOS in the spring of 1992, it sold in reasonable quantities, doing best with Amiga owners in Europe. Charles Cecil didn’t hesitate to wave the flag on behalf of the continent. “I believe that European graphic artists are the best,” he said — an assertion which the graphics in Lure of the Temptress utterly failed to prove. Thankfully, better things were still to come from Revolution.

Lure of the Temptress did earn enough money to fund a move to better offices in York, with a corresponding uptick in the budget for their next game. Even so, much of the dramatic improvement evinced by said game was the result of a series of chance events that won Revolution the services of arguably the most respected comic-book illustrator of the era. And yes, he was a European. In fact, he hailed from Britain.

In May of 1989, a popular British gaming magazine known as The One published a feature about Watchmen, a two-year-old book which had done much to inculcate the idea of the graphic novel as a respectable literary form. Amidst much speculation about a potential Watchmen film and game — neither of which would appear until decades later — the article somehow managed to avoid mentioning the name of Dave Gibbons, the man who had drawn writer Alan Moore’s story. Understandably annoyed, Gibbons wrote to the magazine to point out the fact of his existence.

By way of apology, The One sent Gibbons a Commodore Amiga and a copy of Deluxe Paint, then devoted five pages to an interview featuring his impressions of those things and many others. As the fact that he had seen the first Watchmen article in the magazine in the first place would indicate, Gibbons was already following the latest developments in computer gaming fairly closely. (In this respect and in many others, the down-to-earth Gibbons was unlike his sometime partner Alan Moore, an unrepentant eccentric and dyed-in-the wool Luddite.)

It seems that computer games are finding their own level in the same way as comics. I think that a lot of games, like a lot of comics it must be said, are pretty banal, and pretty repetitive — sort of like chewing gum. They won’t do you any harm, but on the other hand they aren’t likely to do much good.

I find puzzle games the most interesting. And the flight simulations… Falcon’s brilliant. You get to the point where you think you are there and you find yourself leaning in the chair. Rocket Ranger is very interesting stuff, that to me is like those role-playing gamebooks. It’s a different game every time you play it.

The magazine’s earlier slight was forgiven; Gibbons went on to draw the cover art for at least one issue of The One. More importantly, he met Charles Cecil through the magazine; Cecil was still with Mediagenic at the time and was also chummy with the staff at The One. The two started tentatively to feel one another out, until finally, after making some suggestions here and there for Lure of the Temptress, Gibbons agreed to become the principal illustrator and art director of Beneath a Steel Sky, Revolution’s second game. Not only did he bring his unique talents to the game itself, but the presence on the team of such a high-profile individual did much to drum up interest in the press. Cecil tells of the many journalists who came to the trade shows to meet Gibbons and see the game, in that order. They “began pulling out copies of the old Watchmen comics and Dave spent a while signing the lot. It was very positive, and they were dying to see what he had created in the game.”

Charles Cecil’s games have never been notable for the originality of their subject matter, and Beneath a Steel Sky is no exception to that rule of derivation. It trades in the King’s Quest-like fantasy of Lure of the Temptress for a dystopic science-fiction setting with strong cyberpunk overtones — a mixture of Blade Runner and Neuromancer, not exactly a rare blending among games of the early 1990s. Union City, where this game takes place, is the familiar authoritarian technocracy, a place where class strata have taken on a literal dimension. One has to take originality in such a setting where one can find it: upending a science-fictional trope stretching back at least to Fritz Lang’s classic silent film Metropolis, in Union City the poor and powerless live out their squabbling lives in tenements that scrape the sky, while the rich and powerful live in luxury near ground level. Union City’s most unusual wrinkle of all is the fact that it exists in the far-flung locale of Australia instead of some faded North American or European hegemony. Yet even this fact is disarmingly easy to miss entirely, especially if you happen to be playing the voice-acted CD-ROM version with its many distinctly British and American accents.

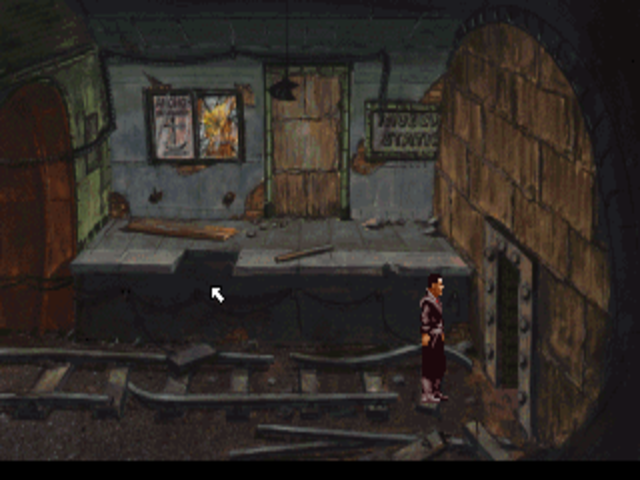

You play a young man named Robert Foster, who as the introduction begins lives with one of the nomadic tribes that inhabit a place known as The Gap, the vast wasteland separating the cities of Australia. (Said wasteland is known as the Outback today…) But then a military raid kills everyone in the tribe except Foster himself; he is spared, to be spirited away by helicopter to Union City for reasons unknown. He escapes when the helicopter crashes over the city before it can reach its final destination, whereupon the game proper begins. As Foster, you must elude your pursuers as you explore Union City’s nooks and crannies, must learn the secret that makes you of such special interest to the powers who control the city — and must bring about their downfall.

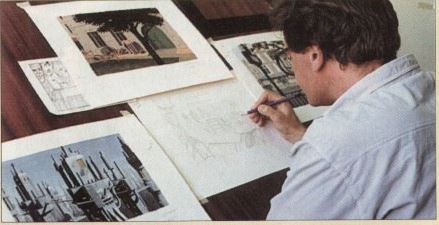

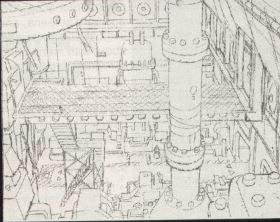

Undoubtedly the strongest aspect of the game — the one thing you’re guaranteed to still remember even years after playing it — is Dave Gibbons’s art. Despite his earlier well-publicized experiments with Deluxe Paint, he elected to draw all of the approximately 90 background scenes for which he was responsible using the same old analog techniques that he had used to bring Watchmen and countless other comics to light. He provided pencil sketches of each scene to Revolution, where an artist named Les Pace, a veteran of such Hollywood productions as Who Framed Roger Rabbit, proceeded to color them in by hand. Only then were the illustrations scanned in on an Apple Macintosh, that being the most affordable platform at the time with good support for 24-bit color. Finally, these “master plates” could be down-sampled to come within the capabilities of Revolution’s two primary target platforms for the finished game: MS-DOS machines with VGA graphics cards (which allowed a maximum of 256 onscreen colors) and the Commodore Amiga (which allowed just 32).

Even in these degraded forms, the game’s imagery is striking. Inspired to some extent by the collapsing factories of hardscrabble Hull, Revolution Software’s original home, Union City manages to be varied but also of a piece, dingy but also coldly clinical, a warren of boldly vertiginous drops and furtively claustrophobic corners. Unlike many games during this era of exploding technological innovation, when the desire for spectacle could often overwhelm consistency and coherence, there’s a thoroughgoing visual aesthetic to Beneath a Steel Sky that stems from something more than a desire to show off the technology that powers it. Charles Cecil’s comment on the subject stood out in an era obsessed with photo-realism in games: “We’re not trying to create reality. We’re trying to create a style.”

The Process

Finally, it was scanned in in 24-bit color. This master copy was then down-sampled to 256 colors (MS-DOS) or 32 colors (Amiga) for inclusion in the game. (The image above is from the Amiga version; those below are from the higher-fidelity MS-DOS version.)

The End Results

The writing in the game is a touch weaker than its visuals; scriptwriter Dave Cummins isn’t incompetent by any means, but nor is he another Alan Moore. As tends to happen constantly in the adventure genre, the overarching “dark, serious” plot gets immediately overrun in the details by a collapse into comedy, a genre which seems far better suited to the outlandish puzzles that are the driving force of most adventure games, this one included.

Still, the blow of this failure of the game to stick to its dramatic guns is eased immensely simply because a lot of the humor is really, truly funny; it never feels forced, something which is by no means the case in all or even most of this game’s competitors. This is wry British humor at its best: it’s sneakily smart, and also a bit more deviously risque than what you might find in a contemporary American game of this ilk. (One running gag, for example, has to do with a skeezy character’s collection of “pussy pictures” — which, yes, turns out just to be pictures of cats.) You begin the game with a sidekick already in your inventory: your childhood friend Joey, a synthetic personality on a circuit board who can be transplanted into various robots as you go along. His sarcastic banter is a great source of fun and oblique hints, such that when he’s not with you in some sort of embodied form you genuinely miss him. In fact, I’d like the game even more if it had more of him in it. He’s prevented from joining the absolute highest ranks of classic adventure-game sidekicks only by the fact that he’s onscreen less than half the time.

If you hate convoluted adventure-game puzzles on principle, the ones here will do nothing to convince you otherwise. If you enjoy them, on the other hand, Beneath a Steel Sky is a solid implementation of their ilk. It’s not a particularly easy game, but nor is it an unusually hard one for its time, and it is consistently logical in its silly adventure-game way. (In this sense as in several others, it stood head and shoulders above its few competitors among homegrown British graphic adventures, whose grasp on the fundamentals of good game design tended to be shaky at best.) It eschews the contemporaneous interactive-movie trend, with its chapter breaks and extended cut scenes, for a more old-school non-linear approach; for the bulk of the game, you have a fairly large area to roam and multiple problems to work on. There’s never a sense that the puzzles were hasty additions inserted just to give the player something to do; they’re part and parcel of a holistic experience.

Vestiges of Revolution’s earlier rhetoric about creating more dynamic worlds do remain here. Characters are still a bit more active than you might find in a Sierra or LucasArts game, and an unusual number of the puzzles rely on analyzing their movements and timing your own actions just right. That said, the most frustrating aspects of Lure of the Temptress have been excised. For the most part, the designers opted to return to the things that were known to work in this genre rather than continuing to blaze problematic new trails — and it must be said that the game is all the better for their conservatism. Likewise, its straightforward one-click interface wasn’t hugely innovative in itself even at the time — this doing-away-with the old menu of verbs was becoming the norm in graphic adventures by this point — but it is a well-executed example of such an interface. All in all, if you like traditional graphic adventures, you’ll find this game to be a sturdy, perhaps occasionally inspired example of the genre.

Beneath a Steel Sky was a European game made at a time when the Commodore Amiga, although slowly sliding past its peak, was still the most popular gaming platform across much of that continent, and thus one that could not be safely ignored by any European studio. Make no mistake: the challenges of making a game that could run on an Amiga at the same time that it could stand on a reasonable par with the latest adventure games on American shelves were immense. The Amiga was slower than the latest MS-DOS machines and was lacking graphically by comparison, and most European Amiga owners didn’t even have a hard drive, much less a CD-ROM drive. And yet, remarkably, Revolution largely pulled it off. Beneath a Steel Sky shipped in March of 1994 on no fewer than fifteen Amiga floppy disks. You had to swap them constantly in order to play it on a machine without a hard drive, but it wasn’t quite aggravating enough to completely destroy the fun of the game itself for an Amiga-owning adventure fan.

Charles Cecil, whose nebbishy appearance concealed a surprisingly down-and-dirty sort of marketing savvy, cast the game not only as Britain’s answer to the adventures of Sierra and LucasArts but as the savior of adventure gaming writ large on the Amiga, coming as it did just as the aforementioned companies were abandoning the platform. He wasn’t above the occasional gratuitous slam against the Americans in interviews which he knew would remain safely ensconced on his side of the ocean: “Most American graphic adventures are a little shallow because the American public doesn’t see plot as important. However, European game players seem to want to think a lot more about what they’re doing, and we’ve tried to reflect that.” Some of his statements in this mode were just bizarre: “The engine Sierra [is] using is outdated. They introduced it five years ago and really haven’t developed it.” For the record, it should be noted that the five years in question encompass Sierra’s move from parser-driven games to point-and-click ones, along with the jump from 16-color EGA graphics to 256-color VGA and the addition of voice acting, just to list a few highlights. To further confuse the situation, Cecil was seeking and winning a contract from Sierra to port King’s Quest VI to the Amiga — something the American company otherwise had no plans to do — at the very same time he was making such comments. Naturally, the European magazines ate it up, awarding his game gold stars pretty much across the board.

Just a month later, Commodore declared bankruptcy. Beneath a Steel Sky was one of the last of its breed on the Amiga.

By way of completing the picture of a work at the crossroads between the old order and the new, Revolution released a voice-acted CD-ROM version for MS-DOS computers shortly after the floppy-based releases. The actors went for the most part uncredited, but it appears that Revolution didn’t look far from home for most of them. The eccentric citizens of Union City deliver their lines with gusto in broad Northern English, a nice contrast to the prim London accents of so many games. Their accents make the humor go down even better, and give the game that much more of a distinctive personality. Meanwhile an American refugee named Adam Henderson voices straight man Robert Foster in the neutral Midwestern tones of a prime-time news anchor, while most of the villains speak Brooklynese straight out of an episode of Law & Order. Go figure…

Helped along by positive reviews and the measure of hype which accompanied the involvement of Dave Gibbons, Beneath a Steel Sky rode Amiga loyalists in Europe and MS-DOS-computer-owning adventure fans in North America to solid sales numbers. Thus Revolution got to live on and make still more games, following a template which was the ironic opposite of their name: solidly constructed adventure games cut from a sturdy traditionalist cloth.

(Sources: Amiga Format of March 1993, December 1993, March 1994; AmigaWorld of December 1993 and August 1994; Amiga Computing of Christmas 1993 and June 1994; Computer Gaming World of July 1992; Computer and Video Games of July 1987 and January 1989; CU Amiga of March 1993 and January 1994; Edge of September 1993; Games TM 9; New Computer Express of August 4 1990; PC Review of May 1992; Questbusters 114; Retro Gamer 56 and 63; The One of May 1989, August 1989, March 1990, November 1991, February 1992, March 1993, and November 1993. Online sources include interviews with Charles Cecil on Gamasutra, Dining with Strangers, and MCV/Develop.

Charles Cecil and Revolution have released Lure of the Temptress and Beneath a Steel Sky as free downloads.)