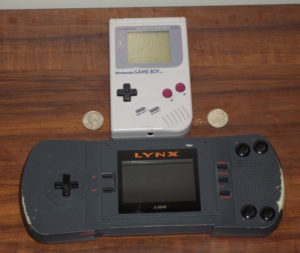

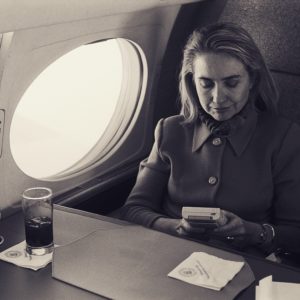

Hillary Clinton plays with her Game Boy on Air Force One in 1993. While history hasn’t recorded with certainty what game she was playing, I’d bet dollars to doughnuts it was Tetris.

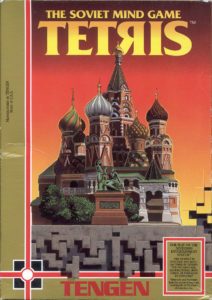

Atari had high hopes for the superlative implementation of Tetris they released for the Nintendo Entertainment System on May 17, 1989, and its initial performance fulfilled all of them, more than justifying their ambitious opening production run of 300,000 cartridges. Indeed, in the first month alone, fueled by positive press and even more positive word of mouth, the Tengen Tetris burned through half of that stock, with sales increasing week over week. Atari clearly had the beginnings of a massive hit on their hands — but not if Nintendo could prevent it.

Nintendo requested that Judge Fern Smith, whose San Francisco courtroom would be the home of most of the legal proceedings in the war between them and Atari, issue a preliminary injunction barring Atari from continuing to sell Tetris until the questions surrounding the rights to it had been fully resolved. Judge Smith agreed to allow the two sides to argue their cases for or against such an injunction beginning on June 15. In the scant few weeks allowed to them, the two companies’ legal teams scrambled to collect documents and depositions in the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union. Nikolai Belikov, Alexey Pajitnov, and the other Russians associated with ELORG thus got to enjoy the novel experience of being interviewed by opposing teams of American lawyers.

The current proceedings were not a full trial on the issue of the rights to the NES Tetris; that wasn’t expected to begin for months, and could then take more months to bring to a final verdict. This preliminary hearing dealt only with the question of whether Atari should be allowed to continue to sell their Tetris over the course of all those months. If Judge Smith thought it likely that Atari would prevail at the full trial, she could give them permission to do so. If she thought the opposite, she could order the Tengen Tetris pulled from the market for the interim.

When in-court arguments began, Atari pressed two separate lines of defense against Nintendo’s charge that the Tetris rights they claimed to own were ill-gotten. They hoped at least one of them would stick.

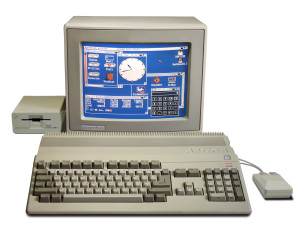

One line of defense accepted for the sake of argument the definition of “computer systems” as “PC computers which consist of a processor, monitor, disk drive(s), keyboard, and operation system” which was found in the revised contract Robert Stein had signed with ELORG the previous February. The NES did in fact — or at any rate potentially could — meet this definition, Atari argued. For proof, they looked to the console’s Japanese incarnation. There it was known, conveniently for Atari’s purposes, as the Nintendo Famicom, short for “Family Computer.” As that name would imply, Nintendo’s long-term goal had always been to turn the platform into more than just a game console. As far back as 1984, they had started selling an add-on kit called Family BASIC, an implementation of the BASIC programming language which came complete with a keyboard for typing in code. Should Judge Smith need more evidence, Atari pointed out that just the previous year Nintendo of Japan had introduced the Family Computer Communications Network System, a modem allowing Nintendo owners to take their machines online — albeit, in keeping with Nintendo’s walled-garden philosophy, only to access Nintendo’s own network. Once online, a Famicom could be used to play games with others, but could also be used to access a whole range of other information and services, from an encyclopedia to stock reports, from a travel agency to mail-order retail kiosks.

Sure, these things had only happened in Japan to date, but the North American NES was at bottom the same machine as the Japanese Famicom. All signs pointed to the NES as well being given capabilities that moved it from the category of game console to that of full-fledged home computer. For evidence of that, one needed look no further than Nintendo’s most recent annual report, where plans for a North American version of a Nintendo-branded online service featured prominently: “By employing the Nintendo Entertainment System as a domestic communications terminal, utilizing regular telephone lines, and the establishing of a large-scale network which to this point has been inconceivable, we plan to provide a vital supply of information for the domestic lifestyle in the fields of entertainment, finance, securities, and health management, to mention but a few.” “In court,” said an Atari spokesman, “Nintendo went to great lengths to say that the NES was a toy and its cartridges were the equivalent of Barbie’s arms and legs, but at the same time they were signing up AT&T to use the machine for stock reports. There is a Nintendo computer network in Japan and one planned for the United States. Sounds like a computer to me.”

If Judge Smith was in doubt how seriously Nintendo’s more grandiose schemes should be taken, she needed only ask the Software Publishers Association. The American software industry lived in terror of this potential Nintendo network, as it did of all of Nintendo’s much-rumored plans to use their game console as a Trojan Horse for bringing the walled-garden model of a software marketplace to applications other than games. If and when brought to fruition, such plans might force the entire industry to kowtow to the whims of this one foreign company. Thus the SPA’s support of Atari’s efforts to break into Nintendo’s extant walled garden of videogames by force, before it was too late.

In response to Atari’s claim that the NES effectively was a computer system, Nintendo noted that the contract which they claimed gave them rather than Atari the rights to make Tetris for the NES had been signed between ELORG and Nintendo of America, not Nintendo of Japan; the version of Tetris available for the Famicom in Japan was made by Henk Rogers’s Bullet-Proof Software, and its legitimacy wasn’t an issue to be decided in Judge Smith’s courtroom. Whatever its technical similarities to the Famicom, the North American NES was a separate product, and none of the Japanese accessories which could be construed as turning the Famicom into a “real” computer were available for the NES. If such accessories should become available in the future, the argument might be revisited, but right now the court should deal only in actualities, not hypotheticals.

For their other line of defense, Atari fielded the assertion that the revisions made to the original contract with Robert Stein had been made in bad faith, and that Stein had in fact been tricked into signing the contract. The Russians had originally intended, Atari argued, to license all of the rights to Stein and be done with it before they realized what a big seller the game had the potential to become. When they saw the opportunity to make more money through a deal with Nintendo, they had tried to pull a fast one to duck out of the first agreement. Stein himself testified to all of this in his deposition. Atari’s Dan Van Elderen, who had recently replaced Randy Broweleit at the head of the Tengen subsidiary, claimed the Russians “knew they had sold all those rights until they figured out, counseled by Henk Rogers and Nintendo, that there was a loophole. They realized they could have gotten a lot more money, so they double-dealt us all.” “Something went on between the Russian author and Nintendo,” said Atari’s president Hideyuki Nakajima in a deposition that might have come across better had he shown Alexey Pajitnov the respect of learning his name. “Nintendo knew we had the license, and it urged us to go forward with the game. Nintendo only cared once we filed the antitrust suit against them. They went after us. Howard Lincoln and Arakawa wanted to stop us. It was revenge.”

Nintendo yielded no ground to this argument either. They trotted out depositions from Alexey Pajitnov, Alexander Alexinko, Nikolai Belikov, and others at ELORG, all testifying that they had always understood the contract with Stein as covering only full-fledged personal computers, and had created the revised version merely to clarify what had always been the case. Furthermore, Stein had been given ample time to review this clarified version of the contract, and had signed it of his own free will.

As anyone who has followed the long and winding story of the Tetris negotiations to this point must acknowledge, neither side was presenting anything close to the unvarnished truth. Nevertheless, Judge Smith, who wasn’t privy to the inside details of the case in the way that we are today, had a hard time getting past the presence of a signed contract clearly stating that the rights Stein had licensed applied only to personal computers — which she judged that the NES, whatever it might become in the future, wasn’t as of June of 1989. On June 21, she handed the devastating news to Atari: they must immediately cease manufacturing and selling the Tengen Tetris, unless and until their right to do so was affirmed by the trial which was to follow later in the year. In the meantime, all unsold copies were to be recalled from the retail pipeline and locked away in a warehouse under the supervision of the court.

In a telling sign of which way the winds were blowing, Judge Smith issued no injunction against Nintendo releasing their own NES version of Tetris while both sides prepared for the full trial. But, perhaps wary of attracting her ire when she seemed to be favoring their side, Nintendo opted to hold their version in abeyance as well. Whose Tetris would make it permanently onto store shelves would be decided by a trial which was scheduled to begin in November. Until then, Tetris on the NES would remain in a tense state of stasis.

As the trial date drew near, Nintendo flew Nikolai Belikov to California to become their most important witness. The excitement of a free trip to the Soviet Union’s vision of a Mirror World was rather dampened by the rest of his circumstances. The pressure from Robert Maxwell’s allies inside the Kremlin hadn’t eased. Belikov faced the prospect of losing his career or possibly even his freedom if things went badly in that San Francisco courtroom. “Before my departure, I was invited into the State Committee for Computer Technology,” he remembers, “and they said, if you lose this lawsuit a special commission will be created who will look into how many millions of dollars the Soviet state has lost due to your reckless actions.” Belikov had known his fair share of bureaucratic scuffles during his day, but he had never felt so exposed as he did now. He joked darkly with his new Nintendo friends that if things went south he might just have to defect.

He needn’t have worried; Nintendo’s confidence that Judge Smith was leaning in their direction proved well-founded. The first day of the trial — November 13, 1989 — was a dream for Nintendo and a nightmare for Atari. Judge Smith came into the courtroom that morning only briefly, to announce that, having reviewed the evidence that had already been submitted, she saw no need to hear from witnesses or otherwise go through the motions of a full trial. She announced a summary judgment declaring Nintendo to be entirely in the right, Atari entirely in the wrong. The former was free to release their NES version of Tetris at their convenience, while the latter was to destroy their warehoused copies of the game forthwith. After months of preparation and buildup, the “trial” was over well before lunchtime. Atari announced that they would appeal the summary judgment, as you do in such circumstances, but soon decided that doing so would just mean more lawyers’ fees down the drain.

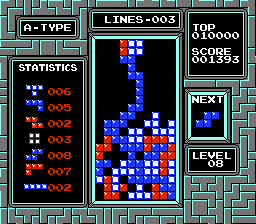

So, the judgment was allowed to stand, and the remaining copies of the Tengen Tetris were destroyed. Thanks to their relative scarcity as well as their sheer quality as the best implementation of Tetris ever to grace the NES, those copies which were sold during the one month the game spent on the market have become collectors’ items today, fetching prices of $100 or more.

For the Nintendo/ELORG camp, it was all over but the celebrations. “It made both Mr. Arakawa and I feel wonderful, just great” says Howard Lincoln. “There was jubilation,” says Henk Rogers. Rogers took Belikov out on the town. “I remember he turned up the stereo. We were breaking all the laws,” says Belikov. “He was speeding around San Francisco on the hilly streets. I was, honestly speaking, still in shock. Everything was happening in slow motion. The joy came a lot later. The fear started to go. I could go… I could go back!”

When Belikov did go back to Moscow, the money that came flowing the Russians’ way thanks to the deals he had made was finally enough to quiet the storm that had been battering at ELORG’s doors for so long. Robert Maxwell came to ascribe his friend Mikhail Gorbachev’s failure to deliver on his promise to oust “the Japanese company” to his need to placate certain factions within the Kremlin in order to maintain his grip on the General Secretary post: “He said other people in the government felt strongly that it should go the other way, so we stopped.” After threatening to create an international political scandal out of the issue, Maxwell allowed cooler heads to prevail in the end, washing his hands of the whole matter in that way that only the very rich are generally empowered to do. “You take your lumps along the way,” he said with a shrug. As big a deal as Tetris was in the realm of videogames, it was small potatoes in the context of his overall business empire.

And so, not without a whiff of anticlimax, the final questions about who was the rightful owner of Tetris in each of its incarnations were definitively resolved. ELORG, Bullet-Proof, and Nintendo were the winners, the new order they had sculpted in February and March of 1989 having been given the stamp of approval of an American court. Atari, Stein’s Andromeda Software, and Mirrorsoft were the losers. Somewhere in between was Spectrum Holobyte, who had managed — as much due to circumstance as conscious choice — to sit out the conflict as something of a neutral party, and was rewarded by being allowed to continue enjoying the strong sales of the North American personal-computer version of Tetris. Those sales, which would ultimately total several hundred thousand, might not have been a patch on the numbers the NES version would soon be racking up, but they suited a small computer-game publisher like Spectrum Holobyte just fine.

As for the right and wrong of it all… well, the ethical waters surrounding Tetris had been muddy virtually from the moment Robert Stein had seen Vadim Gerasimov’s implementation of the game running on a computer in Budapest and tried to buy it from his Hungarian programmers without acknowledging where it had actually come from. Still, whomever we decide to label as the heroes and villains of this twisted tale, and in whatever ethical light we choose to see the other aspects of Atari’s war against Nintendo, it’s hard not to feel that Atari got a raw deal when it came to Tetris. They licensed the rights in good faith and created a superlative version of the game, only to be forced to pay for the sins of others. But all’s fair in love and (business) war. “It was revenge,” says Howard Lincoln of spoiling Atari’s plans and spiriting away what would go on to become the most popular videogame in history. “And you know how sweet revenge can be.” I’m not sure I do, actually — but I have a feeling that Howard Lincoln does.

Nintendo’s NES Tetris hit the market within days of the summary judgment, hoping to capitalize on whatever was left of the Christmas rush. The game would spend a year on the NES top-ten chart and sell at least 6 million copies over the course of its unusually long commercial lifetime. Yet, just as Lincoln, Arakawa, and Rogers had all suspected, and despite all the drama that had surrounded its release, this version of Tetris didn’t turn out to be the one that mattered most.

The Nintendo Game Boy had arrived in North American stores near the end of the summer of 1989, just in time to create a major headache for the teachers of all those members of Generation Nintendo who headed back to school with the gadgets in their backpacks. Game Boy would go on to become Nintendo’s second massive success story. In fact, it would become even more massive a success story than the first, selling almost 120 million units — roughly twice the total worldwide sales of the NES and Famicom lines — over the course of more than a decade in production.

For the first handful of those years, every single one of the millions upon millions of Game Boys that were sold in North America and Europe included a copy of Tetris. It was thus the Game Boy that spread Tetris absolutely everywhere, making it popular on a scale that no videogame had ever managed before nor has ever quite managed since. The irony in this is rich. While everyone’s attention had been focused on the grand legal showdown between Nintendo and Atari, the handheld Tetris, the rights to which had never been seriously disputed by anyone since Henk Rogers had picked them up on his first visit to Moscow, was the Tetris which ultimately proved to be the most important by far.

In discussing such a divine synergy as that enjoyed by the Game Boy and Tetris, it’s impossible to state precisely which half of the equation got more out of the deal. Still, the preponderance of the evidence would seem to indicate that Tetris gave at least as much as it got. In the process, it did nothing less than identify a whole new potential market for videogames.

Nintendo of America’s success to date had been predicated on knowing exactly who constituted the natural market for their games, and targeting that market with pinpoint precision. Nintendo Power, the lifeline that linked the Nintendo executive suites to the youthful Generation Nintendo, looked not at all different from other magazines aimed at teens and preteens, full of exclamation points and eye-popping splashes of color plastered across every page. A closer look at the contents only cemented the impression: alongside articles about the games themselves were profiles of teen pop stars like Debbie Gibson and earnest admonitions not to let playing Nintendo supersede doing homework. While a story might occasionally surface, in Nintendo Power or for that matter in a newspaper, about a sheepish parent who had somehow picked up a Super Mario Bros. obsession, such anecdotes were amusing for the very reason that they were such an exception to the demographic rule.

But as the Game Boy’s sales only continued to increase following a launch that had been explosive beyond even Nintendo’s dearest hopes, the company’s customer surveys began to reveal a curious piece of information: many, many adults were playing with the Game Boys they had bought for their children as much or more than said children were. The adults in question were largely well-educated professionals who would never have dreamed of darkening the doors of an arcade or picking up an NES controller. Yet here they were, playing Game Boy. And, it didn’t take much further probing to reveal, the game they were almost universally playing was Tetris.

Surprised by this development but far from averse to it, Nintendo began aiming some of their marketing fusillade at adults. Game Boy advertisements were soon appearing in in-flight magazines, targeted explicitly at the business travelers leafing through their pages:

If you’re reading this ad, you’re very bored. You’ve mastered the safety instructions in every language, and the flight attendant won’t give you any more almonds. Now what? Game Boy won’t ask you for your dessert, and fits just as neatly into the mouth of that screaming child beside you as it does into your briefcase.

The cleverest of all the new advertisements neatly reversed the typical family’s videogame supply chain to suit the changing times: “This Father’s Day, treat Dad like a kid!”

Many of the Game Boys sold via such advertisements were literally never used to play any other game than Tetris. Reports had it that some players, concerned over a tendency the cartridge had to fall out of its slot as it aged, actually glued it into place — thus cementing permanently, as it were, the link between Game Boy and Tetris. This state of affairs wasn’t entirely ideal in Nintendo’s view — they sold the Game Boy cheap in the expectation of making a lot more money off the game cartridges they would later sell for it, a plan which a Game Boy that was used for nothing other than playing Tetris rather nullified — but Game Boy sales on the whole were so absurdly strong that there was little room to really complain.

Careful readers will note that I described the combination of the Game Boy and Tetris as “identifying a whole new potential market for videogames” rather than creating one in any sustained sense. For years after millions of adults went Tetris crazy, game makers — including the usually astute Nintendo — were remarkably slow to follow up this success. Many students of gaming history date the true beginning of the modern market for casual games to the release of Bejeweled in 2001. Yet if you ask these same students about the first casual game, full stop, the majority will point back to Tetris. Not coincidentally, Bejeweled and its many descendants all inhabit a subgenre broadly known as the “matching game,” which has Tetris as its forefather. When writing A Casual Revolution, his book on the phenomenon of casual games, Jesper Juul interviewed dozens of casual players. One of the constants of these interviews emerges when the players are asked about their experience of playing games before discovering modern casual-game portals like Big Fish Games. As often as not, Tetris is the first thing to spring into their minds. This indicates not simply that many of these casual gamers once played Tetris, but that they also identify it as something broadly like the games they enjoy today. Tetris gave them a glimpse of something circa 1990 that the games industry never fully managed to deliver to them again until the following decade.

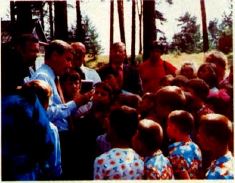

Eager like all Tetris publishers to use the game’s origins in the Mirror World for marketing purposes, Nintendo did a fair amount of outreach in the Soviet Union. Here Howard Lincoln visits a Russian summer camp, where he passes out free Game Boys.

Juul published his book in 2010, when countless millions were still playing Tetris on the so-called “feature phones” of the time. For all the anecdotes from Tetris‘s heyday about playing it on work PCs in office cubicles, it was always the collision between the game and a mobile device — whether Game Boy, feature phone, or smartphone — that really brought the magic. It may have taken Tetris five years to make the journey from Alexey Pajitnov’s clunky Elektronika 60 terminal to the svelte little Game Boy, but once it arrived on mobile it was clear that this was where the game would truly thrive. A great casual game can be played obsessively or sporadically with equal success, and thus really comes into its own when combined with a portable gadget of some stripe and a player with a little — or perhaps sometimes a lot — of time to kill. Game designer Frank Lantz:

Tetris might be the ur-casual game. If you think of casual games as the PopCap-style match-3 puzzle games, Tetris is the blueprint for that, and yet it is possible to play Tetris in drunken binges. You are addicted to this activity, this repetitious thing you can’t walk away from for hours. When you finally put it down, you are groggy and have a headache. Or it is possible to play Tetris when you are standing in the line at the DMV and you think, “Okay, I am bored, I’ve got five minutes to fill and I will play some Tetris.” It is still Tetris in either sense.

Tetris, in other words, molds itself to your life rather than the other way around. Rather than gaming as lifestyle, it’s gaming as lifestyle accessory. It turns out that, contrary to almost every one of the games industry’s pre-millennial instincts, there’s even more money to be made in the latter than the former. Tetris, the urtext of the casual game, had sold an estimated 170 million physical copies and 425 million digital copies by 2016, earning nearly $1 billion in the process. By most meaningful measures, it is indeed the most popular videogame in history. A game that somehow managed to become iconic without containing any actual icons — no characters, no story, no essential style or look — it must also be, in light of the market it did so much to identify, at the very least in the conversation for the title of most important videogame of all time.

In 1993, Tetris became the first videogame to be played in space when cosmonaut Aleksandr Serebrov took his Game Boy with him into orbit. This well-publicized event was as close as the Russians ever came to achieving their hopes for a grand promotional partnership between Nintendo and the Soviet space program.

(Sources: the books Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World by David Sheff, The Tetris Effect: The Game That Hypnotized the World by Dan Ackerman, and A Casual Revolution: Reinventing Video Games and Their Players by Jesper Juul; the BBC television documentary From Russia with Love; Nintendo Power of July/August 1989, September/October 1989, and November/December 1989; The New York Times of June 22 1989 and December 21 1989.)